YouTube live: RBI Guidelines on Default Loss Guarantee

Anita Baid in conversation with Vinod Kothari

Live on YouTube – 20th June, 2023 | 5:00 P.M. – https://www.youtube.com/@vinodkotharicompany3966/videos

Loading…

Loading…

Anita Baid in conversation with Vinod Kothari

Live on YouTube – 20th June, 2023 | 5:00 P.M. – https://www.youtube.com/@vinodkotharicompany3966/videos

Loading…

Loading…

We invite you all to join us at the 10th Securitisation Summit, 2022 on 27th May 2022. You are sure to meet the who’s-who of the Indian structured finance space – the originators, investors, rating agencies, legal counsels, accounting experts, global experts, and of course, regulators. The details can be accessed here.

– Siddarth Goel (finserv@vinodkothari.com)

The stage of development of financial markets infrastructure in a country, amongst many other things, is a mirror of sound legal regulations, corporate governance, judicial certainty, and debtor protection regime within the country. The inflow of global capital is quintessential for financial markets development and allocation of adequate capital resources in growth sectors. In a move to make India a hub for global capital flow, Gujarat International Finance Tech-City (GIFT) has been established as a globally benchmarked International Financial Service Centre (GIFT-IFSC). GIFT-IFSC is India’s first dominant gateway for global capital flows in and out of the country. The GIFT IFSC supports a gamut of financial services inter alia, banking, insurance, asset management, and other financial market activities. Prior to dealing with the regulatory framework governing financial units established in GIFT-IFSC, it is important to understand the broad function of an IFSC.

IFSCs are the Offshore Financial Centers (OFCs) that cater to customers outside their own jurisdiction. IMF defines OFCs as any financial center where the offshore activity takes place. However, this does not limit financial institutions in OFCs from undertaking domestic transactions. Therefore practical definition propounded by IMF is;

“OFC is a center where the bulk of financial sector activity is offshore on both sides of the balance sheet, (that is the counterparties of the majority of financial institutions liabilities and assets are non-residents), where the transactions are initiated elsewhere, and where the majority of the institutions involved are controlled by non-residents.”

Units set up in GIFT-IFSC can broadly be categorised on the basis of business activity intended to being undertaken by the entity.

This write-up covers regulations governing banking and financial services undertaken by Banking Units and Finance Companies set up in IFSC. The first part touches upon the benefits of setting up a unit in IFSC. The second part covers Banking Units and permitted financial activities. The third part covers Financial Companies in IFSC along with permissible activities and capital requirements. The fourth part covers financial service transactions to and fro between a financial unit based in IFSC and domestic tariff area (DTA). The last part deals with the applicable KYC/PMLA compliances and the currency of transactions with units based in IFSC.

-Financial Services Division (finserv@vinodkothari.com)

The Supreme Court of India (‘SC’ or ‘Court’) had given its judgment in the matter of Small Scale Industrial Manufacturers Association vs UOI & Ors. and other connected matters on March 23, 2021. The said order of SC put an end to an almost ten months-long legal scuffle that started with the plea for a complete waiver of interest but edged towards waiver of interest on interest, that is, compound interest, charged by lenders during Covid moratorium. While there is no clear sense of direction as to who shall bear the burden of interest on interest for the period commencing from 01 March 2020 till 31 August 2020. The Indian Bank’s Association (IBA) has made representation to the government to take on the burden of additional interest, as directed under the Supreme Court judgment. While there is currently no official response from the Government’s side in this regard, at least in the public domain in respect to who shall bear the interest on interest as directed by SC. Nevertheless, while the decision/official response from the Government is awaited, the RBI issued a circular dated April 07, 2021, directing lending institutions to abide by SC judgment.[1] Meanwhile, the IBA in consultation with banks, NBFCs, FICCI, ICAI, and other stakeholders have adopted a guideline with a uniform methodology for a refund of interest on interest/compound interest/penal interest.

We have earlier covered the ex-gratia scheme in detail in our FAQs titled ‘Compound interest burden taken over by the Central Government: Lenders required to pass on benefit to borrowers’ – Vinod Kothari Consultants>

In this write-up, we have aimed to briefly cover some of the salient aspects of the RBI circular in light of SC judgment and advisory issued by IBA.

– Siddarth Goel (finserv@vinodkothari.com)

A payment denotes the performance or discharge of an obligation to pay, which may or may not involve money transfer. Payment is therefore a financial obligation in whatever parties have agreed constituting a payment. A payment and settlement system could be understood as a payments market infrastructure that facilitates the flow of funds in satisfaction of a financial obligation. The need for a payment system is an integral part of commerce. From the use of a payment system in an e-commerce purchase, a debit or credit card fund transfer, stock or share purchase. The payment obligation can also be settled without the presence of any financial intermediary (peer-to-peer). The payment transaction need not always be settled in money, it could be settled in security, commodity, or any other obligation as may be decided by payment system participants.

One of the earlier known payment mechanisms was the barter system. With the evolution of civilisation, the world moved to a system supported by tokens and coins that are still prevalent and are widely used as the mode of payment. The payment mechanism supported by physical currency notes or coins is simple, as it offers peer-to-peer, real-time settlement of obligation between the parties, by way of physical transfer of note or coin from one party to another.

In contemporary electronic payment systems, the manner of flow of funds from one payment system participant to another is central to the security, transparency, and stability of the payment system and financial system as a whole. The RBI’s main objective is to maintain public confidence in payment and settlement systems, while the other function being to upgrade and introduce safe and efficient modes of payment systems. The RBI is also the banker to all scheduled banks and maintains bank accounts on their behalf. All the scheduled commercial banks have access to a central payment system operated by RBI. Thereby banks have access to liquidity funding line with RBI which have been discussed later in this chapter.

Electronic payments usually involve the transfer of funds via money in bank deposits. While securities settlement system involves trade in financial instruments namely; bonds, equities, and derivatives. The implementation of sound and efficient payment and securities settlement systems is essential for financial markets and the economy. The payment system provides money as a means of exchange, as central banks are in control of supplying money to the economy which cannot be achieved without public confidence in the systems used to transfer money. It is essential to maintain stability of the financial systems, as default under very large value transfers create the possibilities of failure that could cause broader systemic risk to other financial market participants. There is a presence of negative externality that can emanate from a failure of a key participant in the payment system.[1]

-Siddarth Goel (finserv@vinodkothari.com)

The penetration of electronic retail payments has witnessed a steep surge in the overall payment volumes during the latter half of the last decade. One of the reasons accorded to this sharp rise in electronic payments is the exponential growth in online merchant acquisition space. An online merchant is involved in marketing and selling its goods and/or services through a web-based platform. The front-end transaction might seem like a simple buying-selling transaction of goods or services between a buyer (customer) and a seller (merchant). However, the essence of this buying-selling transaction lies in the payment mode or methodology of making/accepting payments adopted between the customer and the merchant. One of the most common ways of payment acceptance is that the merchant establishes its own payment integration mechanism with a bank such that customers are enabled to make payments through different payment instruments. In such cases, the banks are providing payment aggregator services, but the market is limited usually to the large merchants only. Alternatively, merchants can rely upon third-party service providers (intermediary) that facilitate payment collection from customers on behalf of the merchant and thereafter remittance services to the merchant at the subsequent stage – this is regarded as a payment aggregation business.

The first guidelines issued by the RBI governing the merchant and payment intermediary relationship was in the year 2009[1]. Over the years, the retail payment ecosystem has transformed and these intermediaries, participating in collection and remittance of payments have acquired the market-used terminology ‘Payment Aggregators’. In order to regulate the operations of such payment intermediaries, the RBI had issued detailed Guidelines on Regulation of Payment Aggregators and Payment Gateways, on March 17, 2020. (‘PA Guidelines’)

The payment aggregator business has become a forthcoming model in the online retail payments ecosystem. During an online retail payment by a customer, at the time of checkout vis-à-vis a payment aggregator, there are multiple parties involved. The contractual parties in one single payment transaction are buyer, payment aggregator, payment gateway, merchant’s bank, customer’s bank, and such other parties, depending on the payment mechanism in place. The rights and obligations amongst these parties are determined ex-ante, owing to the sensitivity of the payment transaction. Further, the participants forming part of the payment system chain are regulated owing to their systemic interconnectedness along with an element of consumer protection.

This write-up aims to discuss the intricacies of the regulatory framework under PA Guidelines adopted by the RBI to govern payment aggregators and payment gateways operating in India. The first part herein attempts to depict growth in electronic payments in India along with the turnover data by volumes of the basis of payment instruments used. The second part establishes a contrast between payment aggregator and payment gateway and gives a broad overview of a payment transaction flow vis-à-vis payment aggregator. The third part highlights the provisions of the PA Guidelines and establishes the underlying internationally accepted best principles forming the basis of the regulation. The principles are imperative to understand the scope of regulation under PA Guidelines and the contractual relationship between parties forming part of the payment chain.

The RBI in its report stated that the leverage of technology through the use of mobile/internet electronic retail payment space constituted around 61% share in terms of volume and around 75% in share in terms of value during FY 19-20.[2] The innovative payment instruments in the retail payment space, have led to this surge in electronic payments. Out of all the payment instruments, the UPI is the most innovative payment instrument and is the spine for growth in electronic payments systems in India. Chart 1 below compares some of the prominent payment instruments in terms of their volumes and overall compounded annual growth rate (CAGR) over the period of three years.

The payment system data alone does not show the complete picture. In conformity with the rise in electronic payment volumes, as per the Government estimates the overall online retail market is set to cross the $ 200 bn figure by 2026 from $ 30 bn in 2019, at an expected CAGR of 30 %.[4] India ranks No. 2 in the Global Retail Development Index (GRDI) in 2019. It would not be wrong to say, the penetration of electronic payments could be due to the presence of more innovative products, or the growth of online retail has led to this surge in electronic payments.

The terms Payment Aggregator (‘PA’) and Payment Gateways (‘PG’) are at times used interchangeably, but there are differences on the basis of the function being performed. Payment Aggregator performs merchant on-boarding process and receives/collects funds from the customers on behalf of the merchant in an escrow account. While the payment gateways are the entities that provide technology infrastructure to route and/or facilitate the processing of online payment transactions. There is no actual handling of funds by the payment gateway, unlike payment aggregators. The payment aggregator is a front-end service, while the payment gateway is the back-end technology support. These front-end and back-end services are not mutually exclusive, as some payment aggregators offer both. But in cases where the payment aggregator engages a third-party service provider, the payment gateways are the ‘outsourcing partners’ of payment aggregators. Thereby such payments are subject to RBI’s outsourcing guidelines.

One of the most sought-after electronic payments in the online buying-selling marketplace is the payment systems supported by PAs. The PAs are payment intermediaries that facilitate e-commerce sites and merchants in accepting various payment instruments from their customers. A payment instrument is nothing but a means through which a payment order or an instruction is sent by a payer, instructing to pay the payee (payee’s bank). The familiar payment instruments through which a payment aggregator accepts payment orders could be credit cards, debit cards/PPIs, UPI, wallets, etc.

Payment aggregators are intermediaries that act as a bridge between the payer (customer) and the payee (merchant). The PAs enable a customer to pay directly to the merchant’s bank through various payment instruments. The process flow of each payment transaction between a customer and the merchant is dependent on the instrument used for making such payment order. Figure 1 below depicts the payment transaction flow of an end-to-end non-bank PA model, by way of Unified Payment Interface (UPI) as a payment instrument.

In an end-to-end model, the PA uses the clearing and settlement network of its partner bank. The clearing and settlement of the transaction are dependent on the payment instrument being used. The UPI is the product of the National Payments Corporation of India (NPCI), therefore the payment system established by NPCI is also quintessential in the transaction. The NPCI provides a clearing and settlement facility to the partner bank and payer’s bank through the deferred settlement process. Clearing of a payment order is transaction authorisation i.e., fund verification in the customer’s bank account with the payer’s bank. The customer/payer bank debits the customer’s account instantaneously, and PA’s bank transfers the funds to the PA’s account after receiving authorisation from NPCI. The PA intimates the merchant on receipt of payment and the merchant ships the goods to the customer. The inter-bank settlement (payer’s bank and PA’s partner bank) happens at a later stage via deferred net-settlement basis facility provided by the NPCI.

The first leg of the payment transaction is settled between the customer and PA once the PA receives the confirmation as to the availability of funds in the customer’s bank account. The partner bank of PA transfers the funds by debiting the account of PA maintained with it. The PA holds the exposure from its partner bank, and the merchant holds the exposure from the PA. This explains the logic of PA Guidelines, stressing on PAs to put in place an escrow mechanism and maintenance of ‘Core Portion’ with escrow bank. It is to safeguard the interest of the merchants onboarded by the PA. Nevertheless, in the second leg of the transaction, the merchant has its right to receive funds against the PA as per the pre-defined settlement cycle.

The international standards and best practices on regulating Financial Market Infrastructure (FMI) are set out in CPSS-IOSCO principles of FMI (PFMI).[5] A Financial Market Infrastructure (FMI) is a multilateral system among participating institutions, including the operator of the system. The consumer protection aspects emerging from the payment aggregation business model, are regulated by these principles. Based on CPSS-IOSCO principles of (PFMI), the RBI has described designated FMIs, and released a policy document on regulation and supervision of FMIs in India under its regulation on FMIs in 2013.[6] The PFMI stipulates public policy objectives, scope, and key risks in financial market infrastructures such as systemic risk, legal risk, credit risk, general business risks, and operational risk. The Important Retail Payment Systems (IRPS) are identified on the basis of the respective share of the participants in the payment landscape. The RBI has further sub-categorised retail payments FMIs into Other Retail Payment Systems (ORPS). The IRPS are subjected to 12 PFMI while the ORPS have to comply with 7 PFMIs. The PAs and PGs fall into the category of ORPS, regulatory principles governing them are classified as follows:

These principles of regulation are neither exclusive nor can said to be having a clear distinction amongst them, rather they are integrated and interconnected with one another. The next part discusses the broad intention of the principles above and the supporting regulatory clauses in PA Guidelines covering the same.

The legal basis principle lays the foundation for relevant parties, to define the rights and obligations of the financial market institutions, their participants, and other relevant parties such as customers, custodians, settlement banks, and service providers. Clause 3 of PA Guidelines provides that authorisation criteria are based primarily on the role of the intermediary in the handling of funds. PA shall be a company incorporated in India under the Companies Act, 1956 / 2013, and the Memorandum of Association (MoA) of the applicant entity must cover the proposed activity of operating as a PA forms the legal basis. Henceforth, it is quintessential that agreements between PA, merchants, acquiring banks (PA’s Partners Bank), and all other stakeholders to the payment chain, clearly delineate the roles and responsibilities of the parties involved. The agreement should define the rights and obligations of the parties involved, (especially the nodal/escrow agreement between partner bank and payment aggregator). Additionally, the agreements between the merchant and payment aggregator as discussed later herein are fundamental to payment aggregator business. The PA’s business rests on clear articulation of the legal basis of the activities being performed by the payment aggregator with respect to other participants in the payment system, such as a merchant, escrow banks, in a clear and understandable way.

The framework for the comprehensive management of risks provides for integrated and comprehensive view of risks. Therefore, this principle broadly entails comprehensive risk policies, procedures/controls, and participants to have robust information and control systems. Another connecting aspect of this principle is operational risk, arising from internal processes, information systems and disruption caused due to IT systems failure. Thus there is a need for payment aggregator to have robust systems, policies to identify, monitor and manage operational risks. Further to ensure efficiency and effectiveness, the principle entails to maintain appropriate standards of safety and security while meeting the requirements of participants involved in the payment chain. Efficiency is resources required by such payment system participants (PAs/PGs herein) to perform its functions. The efficiency includes designs to meet needs of participants with respect to choice of clearing and settlement transactions and establishing mechanisms to review efficiency and effectiveness. The operational risk are comprehensively covered under Annex 2 (Baseline Technology-related Recommendation) of the PA Guidelines. The Annex 2, inter alia includes, security standards, cyber security audit reports security controls during merchant on-boarding. These recommendations and compliances under the PA Guidelines stipulates standard norms and compliances for managing operational risk, that an entity is exposed to while performing functions linked to financial markets.

An important aspect of payment aggregator business covers merchant on-boarding policies and anti-money laundering (AML) and counter-terrorist financing (CFT) compliance. The BIS-CPSS principles do not govern within its ambits certain aspects like AML/CFT, customer data privacy. However, this has a direct impact on the businesses of the merchants, and customer protection. Additionally, other areas of regulation being data privacy, promotion of competition policy, and specific types of investor and consumer protections, can also play important roles while designing the payment aggregator business model. Nevertheless, the PA Guidelines provide for PAs to undertake KYC / AML / CFT compliance issued by RBI, as per the “Master Direction – Know Your Customer (KYC) Directions” and compliance with provisions of PML Act and Rules. The archetypal procedure of document verification while customer on-boarding process could include:

PAs shall ensure that the merchant’s site shall not save customer’s sensitive personal data, like card data and such related data. Agreement with merchant shall have provision for security/privacy of customer data.

The other critical facet of PA business is the settlement cycle of the PA with the merchants and the escrow mechanism of the PA with its partner bank. Para 8 of PA Guidelines provide for non-bank PAs to have an escrow mechanism with a scheduled bank and also to have settlement finality. Before understanding the settlement finality, it is important to understand the relevance of such escrow mechanisms in the payment aggregator business.

Surely there is a bankruptcy risk faced by the merchants owing to the default by the PA service provider. This default risk arises post completion of the first leg of the payment transaction. That is, after the receipt of funds by the PA from the customer into its bank account. There is an ultimate risk of default by PA till the time there is final settlement of amount with the merchant. Hence, there is a requirement to maintain the amount collected by PA in an escrow account with any scheduled commercial bank. All the amounts received from customers in partner bank’s account, are to be remitted to escrow account on the same day or within one day, from the date amount is debited from the customer’s account (Tp+0/Tp+1). Here Tp is the date on which funds are debited from the customer’s bank account. At end of the day, the amount in escrow of the PA shall not be less than the amount already collected from customer as per date of debit/charge to the customer’s account and/ or the amount due to the merchant. The same rules shall apply to the non-bank entities where wallets are used as a payment instrument.[7] This essentially means that PA entities should remit the funds from the PPIs and wallets service provider within same day or within one day in their respective escrow accounts. The escrow banks have obligation to ensure that payments are made only to eligible merchants / purposes and not to allow loans on such escrow amounts. This ensures ring fencing of funds collected by the PAs, and act as a deterrent for PAs from syphoning/diverting the funds collected on behalf of merchants. The escrow agreement function is essentially to provide bankruptcy remoteness to the funds collected by PA’s on behalf of merchants.

Settlement finality is the end-goal of every payment transaction. Settlement in general terms, is a discharge of an obligation with reference of the underlying obligation (whatever parties agrees to pay, in PA business it is usually INR). The first leg of the transaction involves collection of funds by the PA from the customer’s bank (originating bank) to the PA escrow account. Settlement of the payment transaction between the PA and merchant, is the second leg of the same payment transaction and commences once funds are received in escrow account set up by the PA (second leg of the transaction).

Settlement finality is the final settlement of payment instruction, i.e. from the customer via PA to the merchant. Final settlement is where a transfer is irrevocable and unconditional. It is a legally defined moment, hence there shall be clear rules and procedures defining the point of settlement between the merchant and PA.

For the second leg of the transaction, the PA Guidelines provide for different settlement cycles:

These settlement cycles are mutually exclusive and the PA business models and settlement structure cycle with the merchants could be developed by PAs on the basis of market dynamics in online selling space. Since the end-transaction between merchant and PA is settled on a contractually determined date, there is a deferred settlement, between PA and the merchant. Owing to the rules and nature of the relationship (deferred settlement) is the primary differentiator from the merchants proving the Delivery vs. Payment (DvP) settlement process for goods and services.

Banks operating as PAs do not need any authorisation, as they are already part of the the payment eco-system, and are also heavily regulated by RBI. However, owing to the sensitivity of payment business and consumer protection aspect non-bank PA’s have to seek RBI’s authorisation. This explains the logic of minimum net-worth requirement, and separation of payment aggregator business from e-commerce business, i.e. ring-fencing of assets, in cases where e-commerce players are also performing PA function. Non-bank entities are the ones that are involved in retail payment services and whose main business is not related to taking deposits from the public and using these deposits to make loans (See. Fn. 7 above).

However, one could always question the prudence of the short timelines given by the regulator to existing as well as new payment intermediaries in achieving the required capital limits for PA business. There might be a trade-off between innovations that fintech could bring to the table in PA space over the stringent absolute capital requirements. While for the completely new non-bank entity the higher capital requirement (irrespective of the size of business operations of PA entity) might itself pose a challenge. Whereas, for the other non-bank entities with existing business activities such as NBFCs, e-commerce platforms, and others, achieving ring-fencing of assets in itself would be cumbersome and could be in confrontation with the regulatory intention. It is unclear whether financial institutions carrying financial activities as defined under section 45 of the RBI Act, would be permitted by the regulator to carry out payment aggregator activities. However, in doing so, certain additional measures could be applicable to such financial entities.

The payment aggregator business models in India are typically based on front-end services, i.e. the non-bank entitles are aggressively entering into retail payment businesses by way of providing direct services to merchants. The ability of non-bank entitles to penetrate into merchant onboarding processes, has far overreaching growth potential than merchant on-boarding processes of traditional banks. While the market is at the developmental stage, nevertheless there has to be a clear definitive ex-ante system in place that shall provide certainty to the payment transactions. The CPSS-IOSCO, governing principles for FMIs lays down a good principle-based governing framework for lawyers/regulators and system participants to understand the regulatory landscape and objective behind the regulation of payment systems. PA Guidelines establishes a clear, definitive framework of rights between the participants in the payment system, and relies strongly on board policies and contractual arrangements amongst payment aggregators and other participants. Therefore, adequate care is necessitated while drafting escrow agreements, merchant-on boarding policies, and customer grievance redressal policies to abide by the global best practices and meet the objective of underlying regulation. In hindsight, it will be discovered only in time to come whether the one-size-fits-all approach in terms of capital requirement would prove to be beneficial for the overall growth of PA business or will cause a detrimental effect to the business space itself.

[1] RBI, Directions for opening and operation of Accounts and settlement of payments for electronic payment transactions involving intermediaries, November 24, 2009. https://www.rbi.org.in/scripts/NotificationUser.aspx?Mode=0&Id=5379

[2] Payment Systems in India – Booklet (rbi.org.in)

[3] https://m.rbi.org.in/Scripts/AnnualReportPublications.aspx?Id=1293

[4] https://www.investindia.gov.in/sector/retail-e-commerce

[5] The Bank for International Settlements (BIS), Committee on Payment and Settlement Systems (CPSS) and International Organisation of Securities Commissions (IOSCO) published 24 principles for financial market infrastructures and and responsibilities of central banks, market regulators and other authorities. April 2012 <https://www.bis.org/cpmi/publ/d101a.pdf>

[6]Regulation and Supervision of Financial Market Infrastructures, June 26, 2013 https://www.rbi.org.in/scripts/bs_viewcontent.aspx?Id=2705

[7] CPMI defines non-banks as “any entity involved in the provision of retail payment services whose main business is not related to taking deposits from the public and using these deposits to make loans” See, CPMI, ‘Non-banks in retail Payments’, September 2014, available at <https://www.bis.org/cpmi/publ/d118.pdf>

RBI to regulate operation of payment intermediaries – Vinod Kothari Consultants

– CS Burhanuddin Dohadwala | finserv@vinodkothari.com

GRM means the receipt and processing of complaints from the customer and taking necessary actions to address the same. The GRM of any organization is the gauge to measure its efficiency and effectiveness and provides a picture on how the banks value its customer.

Banks are in service organization. Customer satisfaction and loyalty is prime focus of any bank. Customer complaints are the part and parcel of day to day functioning of banks in India. To address this Reserve Bank of India (‘RBI’) had taken various initiatives over the years for improving customer service and GRM in banks which are as follows:

It is evident from the increasing number of complaints received in the Offices of Banking Ombudsman (‘OBOs’)[2] as per Annexure-1, that greater attention by banks to this area is warranted. More focused attention to customer service and grievance redress was required to ensure satisfactory customer outcomes and greater customer confidence.

Hence, with a view to strengthen and improve the efficacy of the internal GRM of the banks and to provide better customer service RBI vide its press release dated December 04, 2020 w.r.t Statement on Developmental and Regulatory Policies[3] decided:

The aforesaid framework was introduced by RBI on January 27, 2021 vide its notification w.r.t Strengthening of GRM in Banks[4]. The same shall be effective from January 27, 2021 and applicable to all scheduled commercial banks (excluding regional rural banks).

The write-up below shall discuss the framework introduced by RBI and actionables required at the end of the banks.

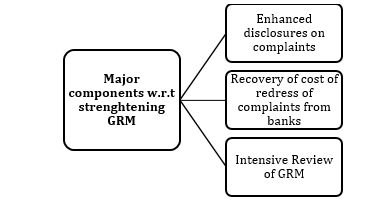

RBI proposes to strengthen GRM in the following areas:

Currently, banks were required to make disclosure regarding customer complaints and grievance redress in their annual report in terms of Para 16.4 w.r.t Analysis and Disclosure of complaints – Disclosure of complaints / unimplemented awards of Banking Ombudsmen along with Financial Results of the Master Circular on ‘Customer Service in Banks’ dated July 01, 2015[5] which are as follows:

(a) No. of complaints pending at the beginning of the year;

(b) No. of complaints received during the year;

(c) No. of complaints redressed during the year;

(d) No. of complaints pending at the end of the year;

(a) No. of unimplemented Awards at the beginning of the year;

(b) No. of Awards passed by the Banking Ombudsmen during the year;

(c) No. of Awards implemented during the year;

(d) No. of unimplemented Awards at the end of the year.

The same is now replaced by the set of granular disclosures to be made by banks in their annual reports as per Annexure 2. These disclosures are intended to provide to the customers of banks and members of public greater insight into the volume and nature of complaints received by the banks from their customers and the complaints received by banks from the OBOs, as also the quality and turnaround time of redress.

Presently, redress of complaints under BO Scheme, 2006[6] (‘BOS’) is cost-free for banks as well as their customers. With a view to ensure that banks discharge this responsibility effectively, the cost of redress of complaints will be recovered from those banks against whom the maintainable complaints[7] in the OBOs exceed their peer group average as provided below. However, grievance redressal under BOS for customers will continue to remain cost-free.

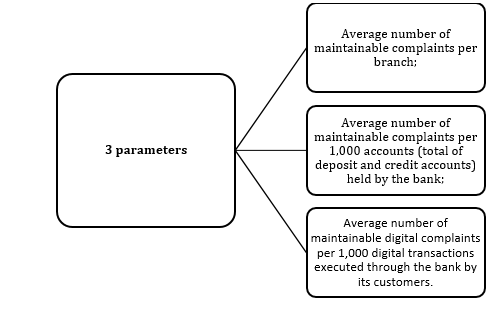

The cost-recovery framework for banks, peer groups based on the asset size of banks as on March 31 of the previous year will be identified, and peer group averages of maintainable complaints received in OBOs would be computed on the following three parameters:

The cost of redressing complaints in excess of the peer group average will be recovered from the banks as follows:

· Excess in any one parameter: 30% of the cost of redressing a complaint[8] (in the OBO) for the number of complaints in excess of the peer group average;

· Excess in any two parameters: 60% of the cost of redressing a complaint for the number of complaints exceeding the peer group average in the parameter with the higher excess;

· Excess in all the three parameters: 100% of the cost of redressing a complaint for the number of complaints exceeding the peer group average in the parameter with the highest excess.

RBI will undertake, as a part of its supervisory mechanism, annual assessments of customer service and grievance redressal in banks based on the data and information available through the CMS, and other sources and interactions.

Banks who are identified as having persisting issues in grievance redress will be subjected to an intensive review of their GRM to better identify the underlying systemic issues and initiate corrective measures. The intensive review shall include but not limited to the following area:

Based on the review, a remedial action plan will be formulated and formally communicated to the banks for implementation within a specific time frame. In case no improvement is observed in the GRM within the prescribed timelines despite the measures undertaken, the banks will be subjected to corrective actions through appropriate regulatory and supervisory measures.

To provide disclosure in the revised format on complaints received by the bank from customers and from the OBOs in the annual report from FY 20-21;

RBI with a view to strengthen and protect the consumers has laid down the aforesaid framework. This will make banks more vigilant to avoid any levy of the cost and supervisory action by RBI.

Annexure A: Chart representing number of complaints received by OBOs

Annexure 2: Part A w.r.t Summary information on complaints received by the bank from customers and from the OBOs

| Sr. No | Particulars | Previous Year | Current Year | |

| Complaints received by the bank from its customers | ||||

| 1. | Number of complaints pending at beginning of the year; | |||

| 2. | Number of complaints received during the year; | |||

| 3. | Number of complaints disposed during the year; | |||

| 3.1 | Of which, number of complaints rejected by the bank; (Newly Inserted) | |||

| 4. | Number of complaints pending at the end of the year; | |||

| Maintainable complaints received by the bank from OBOs | ||||

| 5. | Number of maintainable complaints received by the bank from OBOs; (Newly Inserted) | |||

| 5.1 | Of 5, number of complaints resolved in favour of the bank by BOs; (Newly Inserted) | |||

| 5.2 | Of 5, number of complaints resolved through conciliation/mediation/advisories issued by BOs; (Newly Inserted) | |||

| 5.3 | Of 5, number of complaints resolved after passing of Awards by BOs against the bank; (Newly Inserted) | |||

| 6. | Number of Awards unimplemented within the stipulated time (other than those appealed) | |||

| Note: Maintainable complaints refer to complaints on the grounds specifically mentioned in BO Scheme 2006 and covered within the ambit of the Scheme. | ||||

Annexure 2: Part B w.r.t Top five grounds of complaints received by the bank from customers (Newly Inserted)

| Grounds of complaints, (i.e. complaints relating to) | Number of complaints pending at the beginning of the year | Number of complaints received during the year | % increase/ decrease in the number of complaints received over the previous year | Number of complaints pending at the end of the year | Of 5, number of complaints pending beyond 30 days | |

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | |

| Current Year | ||||||

| Ground-1 | ||||||

| Ground-2 | ||||||

| Ground-3 | ||||||

| Ground-4 | ||||||

| Ground-5 | ||||||

| Others | ||||||

| Total | ||||||

| Previous Year | ||||||

| Ground-1 | ||||||

| Ground-2 | ||||||

| Ground-3 | ||||||

| Ground-4 | ||||||

| Ground-5 | ||||||

| Others | ||||||

| Total | ||||||

| Note: The master list for identifying the grounds of complaints is as follows:

· ATM/Debit Cards; · Credit Cards; · Internet/Mobile/Electronic Banking; · Account opening/difficulty in operation of accounts; · Mis-selling/Para-banking; · Recovery Agents/Direct Sales Agents; · Pension and facilities for senior citizens/differently abled; · Loans and advances; · Levy of charges without prior notice/excessive charges/foreclosure charges; · Cheques/drafts/bills; · Non-observance of Fair Practices Code; · Exchange of coins, issuance/acceptance of small denomination notes and coins; · Bank Guarantees/Letter of Credit and documentary credits; · Staff behavior; · Facilities for customers visiting the branch/adherence to prescribed working hours by the branch, etc.; · Others. |

||||||

| Our link to YouTube video and other articles can be accessed below:

1. YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCgzB-ZviIMcuA_1uv6jATbg; 2. Other articles w.r.t Financial Sector: http://vinodkothari.com/category/financial-services/ |

[2] As per RBI Annual Report of the Banking Ombudsman Scheme and Ombudsman Scheme for Non-Banking Financial Companies for the year 2018-19:

https://rbidocs.rbi.org.in/rdocs/Publications/PDFs/AR201820190FB8B9072F984910A9FC7BA568B634D8.PDF

[7] Maintainable complaints refer to complaints on the grounds specifically mentioned in BOS 2006 and are covered 1301within the ambit of the Scheme.

[8] Average cost of handling a complaint at the OBOs during the year.

-Siddarth Goel (finserv@vinodkothari.com)

The COVID pandemic last year was surely one such rare occurrence that brought unimaginable suffering to all sections of the economy. Various relief measures granted or actions taken by the respective governments, across the globe, may not be adequate compensation against the actual misery suffered by the people. One of the earliest relief that was granted by the Indian government in the financial sector, sensing the urgency and nature of the pandemic, was the moratorium scheme, followed by Emergency Credit Line Guarantee Scheme (ECLGS). Another crucial move was the allowance of restructuring of stressed accounts due to covid related stress. However, every relief provided is not always considered as a blessing and is at times also cursed for its side effects.

Amid the various schemes, one of the controversial matter at the helm of the issue was charging of interest on interest on the accounts which have availed payment deferment under the moratorium scheme. The Supreme Court (SC) in the writ petition No 825/2020 (Gajendra Sharma Vs Union of India & Anr) took up this issue. In this regard, we have also earlier argued that government is in the best position to bear the burden of interest on interest on the accounts granted moratorium under the scheme owing to systemic risk implications.[1] The burden of the same was taken over by the government under its Ex-gratia payment on interest over interest scheme.[2]

However, there were several other issues about the adequacy of actions taken by the government and the RBI, filed through several writ petitions by different stakeholders. One of the most common concern was the reporting of the loan accounts as NPA, in case of non-payment post the moratorium period. The borrowers sought an extended relief in terms of relaxation in reporting the NPA status to the credit bureaus. Looking at the commonality, the SC took the issues collectively under various writ petitions with the petition of Gajendra Sharma Vs Union of India & Anr. While dealing with the writ petitions, the SC granted stay on NPA classification in its order dated September 03, 2020[3]. The said order stated that:

“In view of the above, the accounts which were not declared NPA till 31.08.2020 shall not be declared NPA till further orders.”

The intent of granting such a stay was to provide interim relief to the borrowers who have been adversely affected by the pandemic, by not classifying and reporting their accounts as NA and thereby impacting their credit score.

The aforesaid order dated September 03, 2020, has also led to the creation of certain ambiguities amongst banks and NBFCs. One of them being that whether post disposal of WP No. 825/2020 Gajendra Sharma (Supra), the order dated September 03, 2020, should also nullify. While another ambiguity being that whether the stay is only for those accounts that have availed the benefit under moratorium scheme or does it apply to all borrowers.

It is pertinent to note that the SC was dealing with the entire batch of writ petitions while it passed the common order dated September 03, 2020. Hence, the ‘stay on NPA classification’ by the SC was a common order in response to all the writ petitions jointly taken up by the court. Thus, the stay order on NPA classification has to be interpreted broadly and cannot be restricted to only accounts of the petitioners or the accounts that have availed the benefit under the moratorium scheme. As per the order, the SC held that accounts that have not been declared/classified NPA till August 31, 2020, shall not be downgraded further until further orders. This relaxation should not just be restricted to accounts that have availed moratorium benefit and must be applied across the entire borrower segment.

The WP No. 825/2020 Gajendra Sharma (Supra) was disposed of by the SC in its judgment dated November 27, 2020[4], whereby in the petition, the petitioner had prayed for direction like mandamus; to declare moratorium scheme notification dated 27.03.2020 issued by Respondent No.2 (RBI) as ultra vires to the extent it charges interest on the loan amount during the moratorium period and to direct the Respondents (UOI and RBI) to provide relief in repayment of the loan by not charging interest during the moratorium period.

The aforesaid contentions were resolved to the satisfaction of the petitioner vide the Ex-gratia Scheme dated October 23, 2020. However, there has been no express lifting of the stay on NPA classification by the SC in its judgment. Hence, there arose a concern relating to the nullity of the order dated September 03, 2020.

The other writ petitions were listed for hearing on December 02, 2020, by the SC via another order dated November 27, 2020[5]. Since then the case has been heard on dates 02, 03, 08, 09, 14, 16, and 17 of December 2020. The arguments were concluded and the judgment has been reserved by the SC (Order dated Dec 17, 2020[6]).

As per the live media coverage of the hearing by Bar and Bench on the subject matter, at the SC hearing dated December 16, 2020[7], the advocate on behalf of the Indian Bank Association had argued that:

“It is undeniable that because of number of times Supreme Court has heard the matter things have progressed. But how far can we go?

I submit this matter must now be closed. Your directions have been followed. People who have no hope of restructuring are benefitting from your ‘ don’t declare NPA’ order.“

Therefore, from the foregoing discussion, it could be understood that the final judgment of the SC is still awaited for lifting the stay on NPA classification order dated September 03, 2020.

While the judgment of the SC is awaited, and various issues under the pending writ petitions are yet to be dealt with by the SC in its judgment, it must be reckoned that banking is a sensitive business since it is linked to the wider economic system. The delay in NPA classification of accounts intermittently owing to the SC order would mean less capital provisioning for banks. It may be argued that mere stopping of asset classification downgrade, neither helps a stressed borrower in any manner nor does it helps in presenting the true picture of a bank’s balance sheet. There is a risk of greater future NPA rebound on bank’s balance sheets if the NPA classification is deferred any further. It must be ensured that the cure to be granted by the court while dealing with the respective set of petitions cannot be worse than the disease itself.

The only benefit to the borrower whose account is not classified NPA is the temporary relief from its rating downgrade, while on the contrary, this creates opacity on the actual condition of banking assets. Therefore, it is expected that the SC would do away with the freeze on NPA classification through its pending judgment. Further, it is always open for the government to provide any benefits to the desired sector of the economy either through its upcoming budget or under a separate scheme or arrangement.

[Updated on March 24, 2021]

The SC puts the final nail to almost a ten months long legal tussle that started with the plea on waiver of interest on interest charged by the lenders from the borrowers, during the moratorium period under COVID 19 relief package. From the misfortunes suffered by the people at the hands of the pandemic to economic strangulation of people- the battle with the pandemic is still ongoing and challenging. Nevertheless, the court realised the economic limitation of any Government, even in a welfare state. The apex court of the country acknowledged in the judgment dated March 23, 2020[8], that the economic and fiscal regulatory measures are fields where judges should encroach upon very warily as judges are not experts in these matters. What is best for the economy, and in what manner and to what extent the financial reliefs/packages be formulated, offered and implemented is ultimately to be decided by the Government and RBI on the aid and advice of the experts.

Thus, in concluding part of the judgment while dismissing all the petitions, the court lifted the interim relief granted earlier- not to declare the accounts of respective borrowers as NPA. The last slice of relief in the judgement came for the large borrowers that had loans outstanding/sanctioned as on 29.02.2020 greater than Rs.2 crores. The court did not find any rationale in the two crore limit imposed by the Government for eligibility of borrowers, while granting relief of interest-on-interest (under ex-gratia scheme) to the borrowers.[9] Thus, the court directed that there shall not be any charge of interest on interest/penal interest for the period during moratorium for any borrower, irrespective of the quantum of loan. Since the NPA stay has been uplifted by the SC, NBFCs/banks shall accordingly start classification and reporting of the defaulted loan accounts as NPA, as per the applicable asset classification norms and guidelines.

The lenders should give credit/adjustment in the next instalment of the loan account or in case the account has been closed, return any amount already recovered, to the concerned borrowers.

[1] http://vinodkothari.com/2020/09/moratorium-scheme-conundrum-of-interest-on-interest/

[2] http://vinodkothari.com/2020/10/interest-on-interest-burden-taken-over-by-the-government/#:~:text=Blog%20%2D%20Latest%20News-,Compound%20interest%20burden%20taken%20over%20by%20the%20Central%20Government%3A%20Lenders,pass%20on%20benefit%20to%20borrowers&text=Of%20course%2C%20the%20scheme%2C%20called,2020%20to%2031.8.

[3] https://main.sci.gov.in/supremecourt/2020/11127/11127_2020_34_16_23763_Order_03-Sep-2020.pdf

[4] https://main.sci.gov.in/supremecourt/2020/11127/11127_2020_34_1_24859_Judgement_27-Nov-2020.pdf

[5] https://main.sci.gov.in/supremecourt/2020/11127/11127_2020_34_1_24859_Order_27-Nov-2020.pdf

[6] https://main.sci.gov.in/supremecourt/2020/11162/11162_2020_37_40_25111_Order_17-Dec-2020.pdf

[7] https://www.barandbench.com/news/litigation/rbi-loan-moratorium-hearings-live-from-supreme-court-december-16

[8] https://main.sci.gov.in/supremecourt/2020/11162/11162_2020_35_1501_27212_Judgement_23-Mar-2021.pdf

[9] Compound interest burden taken over by the Central Government: Lenders required to pass on benefit to borrowers – Vinod Kothari Consultants

[10] Moratorium on loans due to Covid-19 disruption – Vinod Kothari Consultants; also see Moratorium 2.0 on term loans and working capital – Vinod Kothari Consultants

-Vinod Kothari (finserv@vinodkothari.com)

The law relating to collective investment schemes has always been, and perhaps will remain, enigmatic, because these provisions were designed to ensure that enthusiastic operators do not source investors’ money with tall promises of profits or returns, and start running what is loosely referred to as Ponzi schemes of various shades. De facto collective investment schemes or schemes for raising money from investors may be run in elusive forms as well – as multi-level marketing schemes, schemes for shared ownership of property or resources, or in form of cancellable contracts for purchase of goods or services on a future date.

While regulations will always need to chase clever financial fraudsters, who are always a day ahead of the regulator, this article is focused on schemes of shared ownership of properties. Shared economy is the cult of the day; from houses to cars to other indivisible resources, the internet economy is making it possible for users to focus on experience and use rather than ownership and pride of possession. Our colleagues have written on the schemes for shared property ownership[1]. Our colleagues have also written about the law of collective investment schemes in relation to real estate financing[2]. Also, this author, along with a colleague, has written how the confusion among regulators continues to put investors in such schemes to prejudice and allows operators to make a fast buck[3].

This article focuses on the shared property devices and the sweep of the law relating to collective investment schemes in relation thereto.

The legislative basis for collective investment scheme regulations is sec. 11AA (2) of the SEBI Act. The said section provides:

Any scheme or arrangement made or offered by any company under which,

The major features of a CIS may be visible from the definition. These are:

The definition may be compared with section 235 of the UK Financial Services and Markets Act, which provides as follows:

It is conspicuous that all the features of the definition in the Indian law are present in the UK law as well.

Hong Kong Securities and Futures Ordinance [Schedule 1] defines a collective investment scheme as follows:

collective investment scheme means—

One may notice that this definition as well has substantially the same features as the definition in the UK law.

Part (iii) of the definition in Indian law refers to management of the contribution, property or investment on behalf of the investors, and part (iv) lays down that the investors do not have day to day control over the operation or management. The same features, in UK law, are stated in sec. 235 (2) and (3), emphasizing on the management of the contributions as a whole, on behalf of the investors, and investors not doing individual management of their own money or property. The question has been discussed in multiple UK rulings. In Financial Conduct Authority vs Capital Alternatives and others, [2015] EWCA Civ 284, [2015] 2 BCLC 502[4], UK Court of Appeal, on the issue whether any extent of individual management by investors will take the scheme of the definition of CIS, held as follows: “The phrase “the property is managed as a whole” uses words of ordinary language. I do not regard it as appropriate to attach to the words some form of exclusionary test based on whether the elements of individual management were “substantial” – an adjective of some elasticity. The critical question is whether a characteristic feature of the arrangements under the scheme is that the property to which those arrangements relate is managed as a whole. Whether that condition is satisfied requires an overall assessment and evaluation of the relevant facts. For that purpose it is necessary to identify (i) what is “the property”, and (ii) what is the management thereof which is directed towards achieving the contemplated income or profit. It is not necessary that there should be no individual management activity – only that the nature of the scheme is that, in essence, the property is managed as a whole, to which question the amount of individual management of the property will plainly be relevant”.

UK Supreme Court considered a common collective land-related venture, viz., land bank structure, in Asset Land Investment Plc vs Financial Conduct Authority, [2016] UKSC 17[5]. Once again, on the issue of whether the property is collective managed, or managed by respective investors, the following paras from UK Financial Conduct Authority were cited with approval:

The purpose of the ‘day-to-day control’ test is to try to draw an important distinction about the nature of the investment that each investor is making. If the substance is that each investor is investing in a property whose management will be under his control, the arrangements should not be regarded as a collective investment scheme. On the other hand, if the substance is that each investor is getting rights under a scheme that provides for someone else to manage the property, the arrangements would be regarded as a collective investment scheme.

Day-to-day control is not defined and so must be given its ordinary meaning. In our view, this means you have the power, from day-to-day, to decide how the property is managed. You can delegate actual management so long as you still have day-to-day control over it.[6]’

The distancing of control over a real asset, even though owned by the investor, may put him in the position of a financial investor. This is a classic test used by US courts, in a test called Howey Test, coming from a 1946 ruling in SEC vs. Howey[7]. If an investment opportunity is open to many people, and if investors have little to no control or management of investment money or assets, then that investment is probably a security. If, on the other hand, an investment is made available only to a few close friends or associates, and if these investors have significant influence over how the investment is managed, then it is probably not a security.

As is apparent, the definition in sec. 235 of the UK legislation has inspired the draft of the Indian law. It is intriguing to seek as to how the collective ownership or management of real properties has come within the sweep of the law. Evidently, CIS regulation is a part of regulation of financial services, whereas collective ownership or management of real assets is a part of the real world. There are myriad situations in real life where collective business pursuits, or collective ownership or management of properties is done. A condominium is one of the commonest examples of shared residential space and services. People join together to own land, or build houses. In the good old traditional world, one would have expected people to come together based on some sort of “relationship” – families, friends, communities, joint venturers, or so on. In the interweb world, these relationships may be between people who are invisibly connected by technology. So the issue, why would a collective ownership or management of real assets be regarded as a financial instrument, to attract what is admittedly a piece of financial law.

The origins of this lie in a 1984 Report[8] and a 1985 White Paper[9], by Prof LCB Gower, which eventually led to the enactment of the 1986 UK Financial Markets law. Gower has discussed the background as to why contracts for real assets may, in certain circumstances, be regarded as financial contracts. According to Gower, all forms of investment should be regulated “other than those in physical objects over which the investor will have exclusive control. That is to say, if there was investment in physical objects over which the investor had no exclusive control, it would be in the nature of an investment, and hence, ought to be regulated. However, the basis of regulating investment in real assets is the resemblance the same has with a financial instrument, as noted by UK Supreme Court in the Asset Land ruling: “..the draftsman resolved to deal with the regulation of collective investment schemes comprising physical assets as part of the broader system of statutory regulation governing unit trusts and open-ended investment companies, which they largely resembled.”

The wide sweep of the regulatory definition is obviously intended so as not to leave gaps open for hucksters to make the most. However, as the UK Supreme Court in Asset Land remarked: “The consequences of operating a collective investment scheme without authority are sufficiently grave to warrant a cautious approach to the construction of the extraordinarily vague concepts deployed in section 235.”

The intent of CIS regulation is to capture such real property ownership devices which are the functional equivalents of alternative investment funds or mutual funds. In essence, the scheme should be operating as a pooling of money, rather than pooling of physical assets. The following remarks in UK Asset Land ruling aptly capture the intent of CIS regulation: “The fundamental distinction which underlies the whole of section 235 is between (i) cases where the investor retains entire control of the property and simply employs the services of an investment professional (who may or may not be the person from whom he acquired it) to enhance value; and (ii) cases where he and other investors surrender control over their property to the operator of a scheme so that it can be either pooled or managed in common, in return for a share of the profits generated by the collective fund.”

While the intent and purport of CIS regulation world over is quite clear, but the provisions have been described as “extraordinarily vague”. In the shared economy, there are numerous examples of ownership of property being given up for the right of enjoyment. As long as the intent is to enjoy the usufructs of a real property, there is evidently a pooling of resources, but the pooling is not to generate financial returns, but real returns. If the intent is not to create a functional equivalent of an investment fund, normally lure of a financial rate of return, the transaction should not be construed as a collective investment scheme.

[1] Vishes Kothari: Property Share Business Models in India, http://vinodkothari.com/blog/property-share-business-models-in-india/

[2] Nidhi Jain, Collective Investment Schemes for Real Estate Investments in India, at http://vinodkothari.com/blog/collective-investment-schemes-for-real-estate-investment-by-nidhi-jain/

[3] Vinod Kothari and Nidhi Jain article at: https://www.moneylife.in/article/collective-investment-schemes-how-gullible-investors-continue-to-lose-money/18018.html

[4] http://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWCA/Civ/2015/284.html

[5] https://www.supremecourt.uk/cases/docs/uksc-2014-0150-judgment.pdf

[6] https://www.handbook.fca.org.uk/handbook/PERG/11/2.html

[7] 328 U.S. 293 (1946), at https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/328/293/

[8] Review of Investor Protection, Part I, Cmnd 9215 (1984)

[9] Financial Services in the United Kingdom: A New Framework for Investor Protection (Cmnd 9432) 1985

Our Other Related Articles

Property Share Business Models in India,< http://vinodkothari.com/blog/property-share-business-models-in-india/>

Collective Investments Schemes: How gullible investors continue to lose money < https://www.moneylife.in/article/collective-investment-schemes-how-gullible-investors-continue-to-lose-money/18018.html>

Collective Investment Schemes for Real Estate Investments in India, < http://vinodkothari.com/blog/collective-investment-schemes-for-real-estate-investment-by-nidhi-jain/>

-Siddarth Goel (finserv@vinodkothari.com)

“If it looks like a duck, swims like a duck, and quacks like a duck, then it probably is a duck”

The above phrase is the popular duck test which implies abductive reasoning to identify an unknown subject by observing its habitual characteristics. The idea of using this duck test phraseology is to determine the role and function performed by the digital lending platforms in consumer credit.

Recently the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) has constituted a working group to study how to make access to financial products and services more fair, efficient, and inclusive.[1] With many news instances lately surrounding the series of unfortunate events on charging of usurious interest rate by certain online lenders and misery surrounding the threats and public shaming of some of the borrowers by these lenders. The RBI issued a caution statement through its press release dated December 23, 2020, against unauthorised digital lending platforms/mobile applications. The RBI reiterated that the legitimate public lending activities can be undertaken by Banks, Non-Banking Financial Companies (NBFCs) registered with RBI, and other entities who are regulated by the State Governments under statutory provisions, such as the money lending acts of the concerned states. The circular further mandates disclosure of banks/NBFCs upfront by the digital lender to customers upfront.

There is no denying the fact that these digital lending platforms have benefits over traditional banks in form of lower transaction costs and credit integration of the unbanked or people not having any recourse to traditional bank lending. Further, there are some self-regulatory initiatives from the digital lending industry itself.[2] However, there is a regulatory tradeoff in the lender’s interest and over-regulation to protect consumers when dealing with large digital lending service providers. A recent judgment by the Bombay High Court ruled that:

“The demand of outstanding loan amount from the person who was in default in payment of loan amount, during the course of employment as a duty, at any stretch of imagination cannot be said to be any intention to aid or to instigate or to abet the deceased to commit the suicide,”[3]

This pronouncement of the court is not under criticism here and is right in its all sense given the facts of the case being dealt with. The fact there needs to be a recovery process in place and fair terms to be followed by banks/NBFCs and especially by the digital lending platforms while dealing with customers. There is a need to achieve a middle ground on prudential regulation of these digital lending platforms and addressing consumer protection issues emanating from such online lending. The regulator’s job is not only to oversee the prudential regulation of the financial products and services being offered to the consumers but has to protect the interest of customers attached to such products and services. It is argued through this paper that there is a need to put in place a better governing system for digital lending platforms to address the systemic as well as consumer protection concerns. Therefore, the onus of consumer protection is on the regulator (RBI) since the current legislative framework or guidelines do not provide adequate consumer protection, especially in digital consumer credit lending.

The Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) has laid a Special Purpose National Bank (SPNV) charters for fintech companies.[4] The OCC charter begins reviewing applications, whereby SPNV are held to the same rigorous standards of safety and soundness, fair access, and fair treatment of customers that apply to all national banks and federal savings associations.

The SPNV that engages in federal consumer financial law, i.e. in provides ‘financial products and services to the consumer’ is regulated by the ‘Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB)’. The other factors involved in application assessment are business plans that should articulate a clear path and timeline to profitability. While the applicant should have adequate capital and liquidity to support the projected volume. Other relevant considerations considered by OCC are organizers and management with appropriate skills and experience.

The key element of a business plan is the proposed applicant’s risk management framework i.e. the ability of the applicant to identify, measure, monitor, and control risks. The business plan should also describe the bank’s proposed internal system of controls to monitor and mitigate risk, including management information systems. There is a need to provide a risk assessment with the business plan. A realistic understanding of risk and there should be management’s assessment of all risks inherent in the proposed business model needs to be shown.

The charter guides that the ongoing capital levels of the applicant should commensurate with risk and complexity as proposed in the activity. There is minimum leverage that an SPNV can undertake and regulatory capital is required for measuring capital levels relative to the applicant’s assets and off-balance sheet exposures.

The scope and purpose of CFPB are very broad and covers:

“scope of coverage” set forth in subsection (a) includes specified activities (e.g., offering or providing: origination, brokerage, or servicing of consumer mortgage loans; payday loans; or private education loans) as well as a means for the CFPB to expand the coverage through specified actions (e.g., a rulemaking to designate “larger market participants”).[5]

CFPB is established through the enactment of Dood-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act. The primary function of CFPB is to enforce consumer protection laws and supervise regulated entities that provide consumer financial products and services.

“(5)CONSUMER FINANCIAL PRODUCT OR SERVICES The term “consumer financial product or service” means any financial product or service that is described in one or more categories under—paragraph (15) and is offered or provided for use by consumers primarily for personal, family, or household purposes; or **

“(15)Financial product or service-

(A)In general The term “financial product or service” means—(i)extending credit and servicing loans, including acquiring, purchasing, selling, brokering, or other extensions of credit (other than solely extending commercial credit to a person who originates consumer credit transactions);”

Thus CFPB is well placed as a separate institution to protect consumer interest and covers a wide range of financial products and services including extending credit, servicing, selling, brokering, and others. The regulatory environment has been put in place by the OCC to check the viability of fintech business models and there are adequate consumer protection laws.

EU’s technologically neutral regulatory and supervisory systems intend to capture not only traditional financial services but also innovative business models. The current dealing with the credit agreements is EU directive 2008/48/EC of on credit agreements for consumers (Consumer Credit Directive – ‘Directive’). While the process of harmonising the legislative framework is under process as the report of the commission to the EU parliament raised some serious concerns.[6] The commission report identified that the directive has been partially effective in ensuring high standards of consumer protection. Despite the directive focussing on disclosure of annual percentage rate of charge to the customers, early payment, and credit databases. The report cited that the primary reason for the directive being impractical is because of the exclusion of the consumer credit market from the scope of the directive.

The report recognised the increase and future of consumer credit through digitisation. Further the rigid prescriptions of formats for information disclosure which is viable in pre-contractual stages, i.e. where a contract is to be subsequently entered in a paper format. There is no consumer benefit in an increasingly digital environment, especially in situations where consumers prefer a fast and smooth credit-granting process. The report highlighted the need to review certain provisions of the directive, particularly on the scope and the credit-granting process (including the pre-contractual information and creditworthiness assessment).

China has one of the biggest markets for online mico-lending business. The unique partnership of banks and online lending platforms using innovative technologies has been the prime reason for the surge in the market. However, recently the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) and China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission (CBIRC) issued draft rules to regulate online mico-lending business. Under the draft rules, there is a requirement for online underwriting consumer loans fintech platform to have a minimum fund contribution of at least 30 % in a loan originated for banks. Further mico-lenders sourcing customer data from e-commerce have to share information with the central bank.

The main legislation that governs the consumer credit industry is the National Consumer Credit Protection Act (“National Credit Act”) and the National Credit Code. Australian Securities & Investments Commission (ASIC) is Australia’s integrated authority for corporate, markets, financial services, and consumer credit regulator. ASIC is a consumer credit regulator that administers the National Credit Act and regulates businesses engaging in consumer credit activities including banks, credit unions, finance companies, along with others. The ASIC has issued guidelines to obtain licensing for credit activities such as money lenders and financial intermediaries.[7] Credit licensing is needed for three sorts of entities.

The applicants of credit licensing are obligated to have adequate financial resources and have to ensure compliance with other supervisory arrangements to engage in credit activates.

Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) is the regulator for consumer credit firms in the UK. The primary objective of FCA ensues; a secure and appropriate degree of protection for consumers, protect and enhance the integrity of the UK financial system, promote effective competition in the interest of consumers.[8] The consumer credit firms have to obtain authorisation from FCA before carrying on consumer credit activities. The consumer credit activities include a plethora of credit functions including entering into a credit agreement as a lender, credit broking, debt adjusting, debt collection, debt counselling, credit information companies, debt administration, providing credit references, and others. FCA has been successful in laying down detailed rules for the price cap on high-cost short-term credit.[9] The price total cost cap on high-cost short-term credit (HCSTC loans) including payday loans, the borrowers must never have to pay more in fees and interest than 100% of what they borrowed. Further, there are rules on credit broking that provides brokers from charging fees to customers or requesting payment details unless authorised by FCA.[10] The fee charged from customers is to be reported quarterly and all brokers (including online credit broking) need to make clear that they are advertising as a credit broker and not a lender. There are no fixed capital requirements for the credit firms, however, adequate financial resources need to be maintained and there is a need to have a business plan all the time for authorisation purposes.

Countries across the globe have taken different approaches to regulate consumer lending and digital lending platforms. They have addressed prudential regulation concerns of these credit institutions along with consumer protection being the top priority under their respective framework and legislations. However, these lending platforms need to be looked at through the current governing regulatory framework from an Indian perspective.

The typical credit intermediation could be performed by way of; peer to peer (P2P) lending model, notary model (bank-based) guaranteed return model, balance sheet model, and others. P2P lending platforms are heavily regulated and hence are not of primary concern herein. Online digital lending platforms engaged in consumer lending are of significance as they affect investor’s and borrowers’ interests and series of legal complexions arise owing to their agency lending models.[11] Therefore careful anatomy of these models is important for investors and consumer protection in India.

Under the current system, only banks, NBFCs, and money lenders can undertake lending activities. The regulated banks and NBFCs also undertake online consumer lending either through their website/platforms or through third-party lending platforms. These unregulated third-party digital lending platforms count on their sophisticated credit underwriting analytics software and engage in consumer lending services. Under the simplest version of the bank-based lending model, the fintech lending platform offers loan matching services but the loan is originated in books of a partnering bank or NBFC. Thus the platform serves as an agent that brings lenders (Financial institutions) and borrowers (customers) together. Therefore RBI has mandated fintech platforms has to abide by certain roles and responsibilities of Direct Selling Agent (DSA) as under Fair Practice Code ‘FPC’ and partner banks/NBFCs have to ensure Guidelines on Managing Risks and Code of Conduct in Outsourcing of Financial Service (‘outsourcing code’).[12] In the simplest of bank-based models, the banks bear the credit risk of the borrowers and the platform earns their revenues by way of fees and service charges on the transaction. Since banks and NBFCs are prudentially regulated and have to comply with Basel capital norms, there are not real systemic concerns.

However, the situation alters materially when such a third-party lending platform adopts balance sheet lending or guaranteed return models. In the former, the servicer platform retains part of the credit risk on its book and could also give some sort of loss support in form of a guarantee to its originating partner NBFC or bank.[13] While in the latter case it a pure guarantee where the third-party lending platform contractually promises returns on funds lent through their platforms. There is a devil in detailed scrutiny of these business models. We have earlier highlighted the regulatory issues in detail around fintech practices and app-based lending in our write up titled ‘Lender’s piggybacking: NBFCs lending on Fintech platforms’ gurantees’.

From the prudential regulation perspective in hindsight, banks, and NBFCs originating through these third-party lending platforms are not aware of the overall exposure of the platforms to the banking system. Hence there is a presence of counterparty default risk of the platform itself from the perspective of originating banks and NBFCs. In a real sense, there is a kind of tri-party arrangement where funds flow from ‘originator’ (regulated bank/NBFC) to the ‘platform’ (digital service provider) and ultimately to the ‘borrower'(Customer). The unregulated platform assumes the credit risk of the borrower, and the originating bank (or NBFC) assumes the risk of the unregulated lending platform.

In the balance sheet and guaranteed return models, an undercapitalized entity takes credit risk. In the balance sheet model, the lending platform is directly taking the credit risk and may or may not have to get itself registered as NBFC with RBI. The registration requirement as an NBFC emanates if the financial assets and financial income of the platform is more than 50 % of its total asset and income of such business (‘principal business criteria’ see footnote 12). While in the guaranteed return model there is a form of synthetic lending and there is absolutely no legal requirement for the lending platform to get themselves registered as NBFC. The online lending platform in the guaranteed return model serves as a loan facilitator from origination to credit absorption. There is a regulatory arbitrage in this activity. Since technically this activity is not covered under the “financial activity” and the spread earned in not “financial income” therefore there is no requirement for these entities to get registered as NBFCs.[14]