Webinar on KFS & APR – New Rules by RBI on Retail & MSME Lending

-Vinod Kothari and Anita Baid | finserv@vinodkothari.com

Loading…

Loading…

Our related resources on the topic:

-Vinod Kothari and Anita Baid | finserv@vinodkothari.com

Loading…

Loading…

Our related resources on the topic:

All-inclusive APR disclosure; third-party payments also included; no lender-induced changes during the validity period of KFS

-Team Finserv | finserv@vinodkothari.com

(Updated as on April 25, 2024)

The RBI vide its Statement on Developmental and Regulatory Policies dated February 08, 2024 announced its decision to mandate Regulated Entities (REs) to provide Key Fact Statement (KFS) for retail and Micro, Small & Medium Enterprise (MSME) loans.

Following the aforesaid, RBI issued a notification dated April 15, 2024 (Circular) to “harmonise” the instructions in this regard for all REs.

Since the intent of the RBI is to harmonise similar requirements, the KFS Circular overrides similar extant requirements in case of lending by banks to individuals, and digital lending.

Contents

| Meaning and Intent |

| Scope and Applicability |

| Contents of KFS |

| Meaning of Retail Lending |

| Meaning of MSME Lending |

| Validity period and Cooling off period |

| Annualised Percentage Rate |

| Other Requirements |

1. What is KFS?

2. How will KFS help transparency?

The intent is to have simple transparent, and comparable (STC) terms of the loan communicated to the customer upfront. The standardised format provides is simple and concise and has all the necessary details of the loan – annual percentage rate, fees, recovery mechanism, and associated risks in a straightforward format.

3. Has the format of KFS and other disclosures been prescribed?

Yes, the format for KFS has been prescribed in Annex A of the Circular. Further, formats for computation of APR and amortization schedule to be given to the borrower has also been prescribed in Annex B and C of the Circular respectively.

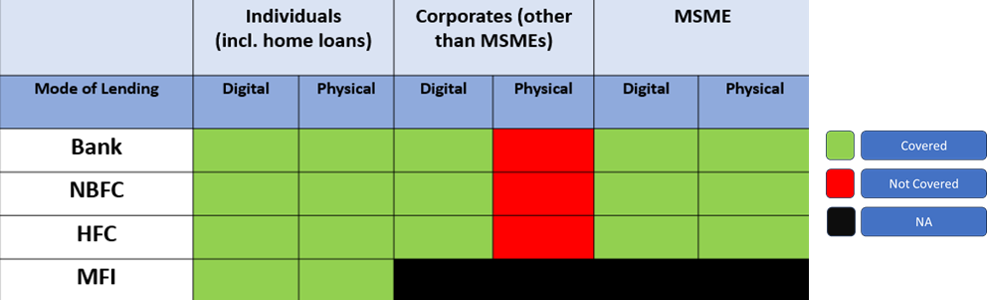

4. Which all entities are covered by the new requirement?

The following entities will be covered under the scope of the Circular –

5. In what kind of loans will KFS be mandatorily applicable?

Coverage of the Circular

6. Will the KFS norms be applicable on Housing Loans as well?

In case of housing loans extended by HFCs, sharing of most important terms and conditions (MITC) are applicable (Para 85.8 read with Annex XII of the HFC Master Directions). MITC is akin to KFS, however, the format of KFS is more focused on interest rate and other charges as well as a few qualitative terms of the loan, whereas MITC provides several other relevant details.

The Circular is addressed to HFCs as well. Further, meaning of “retail lending” (see below) includes home loans as well. In the absence of any other clarification, we would advise lenders to prepare MITC as well as KFS in case of home loans.

7. What happens to the existing circulars on Digital Lending and Microfinance Lending?

The existing provisions for KFS and APR in the Digital Lending Guidelines, MFI Directions and Display of Information by Banks circular shall stand repealed.

8. When does the new requirement become applicable?

The Circular is applicable with effect from October 1, 2024 to all new retail and MSME term loans sanctioned. Further, digital loans, MFI loans and bank finance extended to individuals post the said applicability date would also require to be aligned with the new requirement.

It would, therefore, appear that extant requirements continue to apply from now until 30th September.

It would actually be better for lenders to transition into the new requirement before 1st October, at least on a parallel basis – this will serve as a dry run upto the new requirement from 1st October.

9. In case of banks, what is the applicability of this Circular?

The KFS Circular applies to banks for (a) all loans to individuals, as covered by Display of information by banks; (b) any loans to MSMEs; (c) any microfinance loans; (d) any digital loans.

10. Whether loans under digital lending need to comply with the Circular or will they continue to follow extant guidelines?

The Circular applies to digital loans as well. In fact, it repeals Para 5.1 and 5.2 of the digital lending guidelines dealing with APR and KFS provisions. However, until October 1, 2024, the existing guidelines may continue to be followed.

11. In case of co-lending transactions, is the compliance on the originating co-lender or the funding co-lender?

While specific details of co-lending arrangements are required to be shared with the borrower; the borrower interface is typically done by the originating co-lender. Hence, the originating co-lender should be making the requisite disclosures. Funding co-lenders may ensure that the originating co-lender is making the requisite disclosures.

12. What are the contents/format of KFS?

13. KFS is intended to be a “standardised format”. What is the significance of the format being standardised? Does the lender have the discretion to add/delete fields?

The Circular prescribes for a “standardised format” for KFS. The intent behind this standardisation is to enhance transparency and to facilitate the comparability of the loan terms offered by different lenders. The RBI refers to the KFS as a “standardised format”. Therefore, in our view, the comparability of the KFS will be compromised if it was loaded with new details or subjectivities not envisaged in the standard format.

14.Can the lender, for instance, add clauses like “this is not a sanction letter; the grant of the loan is eventually subject to sanction by the lender’s internal credit committee”, or similar conditionalities?

It is important to note that the format of the KFS is standardised. Therefore, the KFS is expected to remain limited to the fields given in the standardised format. However, the KFS may be an annexure to a sanction letter – see below.

15. Is the present practice of issuing sanction letter redundant? Can a lender issue a sanction letter in addition to KFS?

The KFS is a summarised version of the terms of the loan. However, the grant of the loan itself may have several conditions, typically comprised in the sanction letter. The RBI’s Fair Practices Code refers to a sanction letter – NBFCs shall convey in writing to the borrower in the vernacular language as understood by the borrower by means of sanction letter or otherwise, the amount of loan sanctioned along with the terms and conditions including annualised rate of interest

Hence, first, the sanction letter does not become redundant. Secondly, if there are conditionalities or compliances relating to the loan, the same may be contained in the sanction letter. For example, the borrower may be required to complete some conditions precedent. There are normally several conditions subsequently, commonly called “post-disbursement conditions”. Each of these may be contained in the sanction letter.

15A. The charges mentioned in KFS are an amount X. The KFS also says this amount can be varied by the company. Can the variation of this amount in future be done without the borrower’s consent?

Charges mentioned in KFS may relate to charges payable at the time of the taking the loan, charges over the term of the loan, and may include contingent charges too. Para 8 of the Circular also says that whatever is not disclosed cannot be charged without the explicit of the borrower.

Therefore,

(a) there is no question of charging something that is not a part of the KFS, without the borrowers’ explicit consent.

(b) as for amounts already disclosed, while the company would have reserved the right to vary, however, in our view, these charges cannot be varied as this would disrupt the comparability and standardisation of the KFS.

15B. The KFS circular applies from 1st October 2024 – can the company impose charges not already a part of the loan agreement and make them applicable before 1st October?

Since the KFS circular is coming with the perspective of fairness in practices, and given the fact that the prospective applicability date is merely to allow companies time to adhere to and transition to the new paradigm, the move as proposed will be seen as a way to take undue advantage of the applicability date.

16. Does the issuance of a KFS amount to a binding commitment on the part of the lender to lend?

The language of Explanation below clause 5 of the KFS Circular may give such an impression. It says: “Validity period refers to the period available to the borrower, after being provided the KFS by the RE, to agree to the terms of the loan. The RE shall be bound by the terms of the loan indicated in the KFS, if agreed to by the borrower during the validity period.”

However, in our view, the KFS is only the terms of the loan. The binding force of the KFS during the “validity period” is only on the terms, and not on the grant of the loan itself. If the conditions precedent for availing the loan have been satisfied, the lender will be bound by the terms as contained in the KFS; however, the grant of the loan itself is based on conditions precedent may still form part of the sanction letter.

17. Is it permissible for REs to include additional terms in the KFS alongside those outlined in the standardized format?

The purpose of requiring a standardized KFS for borrowers is to guarantee consistency in loan terms across different lenders, enabling borrowers to make fair comparisons. Therefore, we believe that REs should avoid subjectivity and strictly follow the standardized format outlined in the notification.

18. Can REs charge fees/charges not mentioned in the KFS?

The answer to this is positive as REs can charge fees/charges not mentioned in the KFS with the explicit consent of the borrower.

19. What are Equated Periodic Installments and how are they computed?

Equated Periodic Installment (EPI) refers to a fixed amount comprising both principal and interest repayments that a borrower must pay at regular intervals over a predetermined number of periods to repay a loan fully. These payments ensure the gradual amortization of the loan. When these installments are made on a monthly basis, they are commonly known as Equated Monthly Instalments (EMIs).

20. What is the meaning of retail loans?

Further, it may be noted that credit card receivables, though extended to individuals, are excluded from the purview of the Circular.

21. Give some examples of loans which are not retail lending?

Some examples of loans not considered as retail lending are –

22. What is lending to MSMEs?

Loans to entities satisfying the following conditions and holding Udyam registration as MSMEs:

| Investment in Plant & Machinery | Investment in Equipment | |

| Micro Enterprise | Upto 25 lakh | Upto 10 lakhs |

| Small Enterprise | 25 lakh – 5 crore | 10 lakhs – 2 crore |

| Medium Enterprise | 5 crore – 10 crore | 2 crore – 5 crore |

23. Are all loans to MSMEs covered under the scope of the Circular?

The Circular explicitly states its applicability solely to “MSME Term Loans”. Therefore, we understand that working capital loans or lines of credit extended by REs to MSMEs fall outside the scope of the Circular.

24. What is a Validity Period?

The validity period refers to the timeframe within which the borrower, upon receiving the KFS from the RE, can agree to the loan terms. In case the borrower accepts the terms outlined in the KFS during this validity period, the RE is bound by these terms as indicated in the statement.

25. How long should the Validity Period be?

In terms of the notification, the KFS must possess a validity period of a minimum of three working days for loans with a tenor of seven days or more, and one working day for loans with a tenor of less than seven days.

26. What if the customer does not accept the terms during the validity period?

The RE is only bound by the terms mentioned in the KFS if the same is accepted by the borrower during the validity period. Accordingly, if the borrower fails to accept the KFS terms during the validity period, the RE reserves the right to change the terms after the end of such period.

27. Where will the validity period be disclosed?

Going by the standardised format for KFS provided by RBI, there is no requirement to mention the validity period in the KFS. However, to ensure that the borrower is aware of the same, the validity period can be mentioned in the covering note or sanction letter.

28. What will be considered a Working Day?

Working days would mean Monday to Friday of the week excluding public holidays.

29. What is the difference between the validity period and cooling off period in case of digital loans?

| Validity Period | Cooling off Period |

| Applicable for digital as well as physical loans. | Applicable only for digital loans. |

| Pre-disbursement phase | Post-disbursement phase |

| Provided to the borrower to accept the terms of the loan as indicated in the KFS | Provided to the borrower for exiting digital loans without any pre-payment penalty in case a borrower decides not to continue with the loan. |

| The RE is bound by the terms of the loan if accepted by the borrower during the validity period. | Grants the borrower the right to repay the principal and the proportionate APR during this period. |

30. Is it necessary to provide a validity period to borrowers before approving top-up loans, even if the terms of the top-up loan are identical to those of the existing loan?

Yes, the notification is applicable from October 01, 2024. Accordingly, after this date, KFS should be provided for all top-up loans. Subsequently, following this date, KFS should be furnished for all top-up loans. As a result, borrowers must also be provided with a validity period to accept the terms of the top-up loan.

31. What is APR?

Annual Percentage Rate (APR) is the annual cost of credit to the borrower that includes interest rate and all other charges associated with the loan.

32. What are the components of APR?

The following are the components of APR –

Excluding

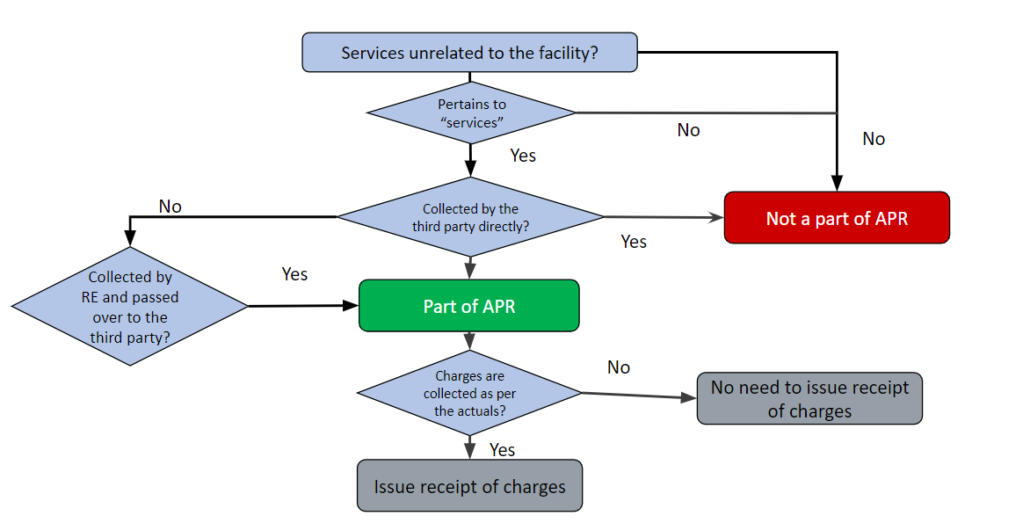

33. Are charges recovered on behalf of third party also a part of the lender’s APR?

Yes, the charges that borrowers pay to the RE, which are passed on to third-party service providers based on actual expenses, like insurance or legal charges, will also be included in the calculation of APR. See the discussion below.

33A. What is the meaning of the expression “service providers”? Can statutory charges such as stamp duty etc also be a part of APR?

The Circular uses the following language: “Charges recovered from the borrowers by the REs on behalf of third-party service providers on actual basis, such as insurance charges, legal charges etc., shall also form part of the APR and shall be disclosed separately.” In our view, the expression “service providers” has been used consciously, to refer to some entities providing services either in relation to the loan, or the subject matter of the loan.

Stamp duty is a statutory charge and is in the nature of a tax/duty payable to the statutory authorities. It cannot be contended that the state is providing any specific service either in relation to the loan or the subject matter of the loan. Hence, in our view, it is only the charges payable in respect of services, recovered by the lender, which should be forming part of the APR.

34. Should charges not directly linked/integrated with the loan, also form part of the APR? Will the answer remain the same even if such charges are deducted from the disbursement amount ?

As regards the inclusion of charges within APR, the essential basis should be the definition of APR, defining it as “the annual cost of credit to the borrower which includes interest rate and all other charges associated with the credit facility”. Therefore, a lender providing a credit facility imposes charges, in addition to interest, by whatever name called, including for third party services which are related to the credit facility or the subject matter of the credit facility, should be forming part of the APR. This will, of course, not include contingent charges such as delinquency penalties, repossession charges, etc.

The charges imposed by lenders may, illustratively, be as follows:

The charges for third-party services, which are typically related to the loan or the subject matter of the loan may be as follows:

The mode of collection of these charges does not matter – that is, these may be charged separately, or may be deducted from the disbursement.

35 .Whether statutory dues would form part of APR?

See answer above.

36. If, for instance, the borrower is required to place a security deposit/cash collateral, which is free of interest, is the impact of the same also captured in the APR?

While the placing of the security deposit may impact the overall cost of the borrower, but in our view, it is inappropriate to incorporate this cashflow as a part of the loan cashflows.

37. In case of loans for vehicles, it is common practice to require the borrower to make a down payment to the supplier. Is the same also captured in the APR?

The APR is computed on the loan amount; down payment is not a part of the loan.

37A In which all cases insurance charges paid to the third party will form a part of the APR ?

We take some illustrative situations below:

37B If cash flows are not at uniform period of time, how will the APR be calculated?

If cash flows are not at uniform periods of time, lenders generally use the XIRR method to calculate interest. Note that IRR formula fails to capture non-equidistant cashflows. However, XIRR is annually compounded rate. It may be converted into a monthly rate by using “nominal” formula, or de-compounding from a year to a month, and then multiplying the result by 12. It should be noted that XIRR is generally greater than APR.

37C In case of a demand loan, will the APR be computed based on the sanctioned amount or on the disbursed amount?

For demand loans, the APR should be calculated based on the sanctioned amount. This reflects the potential maximum cost of credit to the borrower if the borrower chooses to utilize the entire sanctioned amount.

38. Lenders quite often get payouts or subvention from third parties, say vendor, OEM, insurance companies, etc., which supplement the returns of the lender. Are these also disclosed as a part of the APR?

In our view, there is no reason to include payouts by third parties, that is, other than the borrower, as a part of the borrower’s cost of credit.

Having said this, if there are discounts/subventions being given by a vendor, the lender should make a fair disclosure of the discount, showing the same as a deduction from his cost of interest.

Graphical illustration summarising APR

39. What are the disclosure requirements?

Following additional disclosures are to be made by the REs along with KFS –

40. What are the other requirements as per the Circular?

As per the Circular REs are obligated to do the following –

41. In case of digital loans how will RE be able to explain the contents of KFS to the borrower?

For digital loans, REs may have the option to exhibit a pre-recorded video within their application or present a document that elucidates the contents of the KFS.

42. What will be the impact of this circular in existing loans?

REs will not be required to issue KFS in existing loans. However, compliance with this circular will be required for any new loan or top-up loan provided to existing customers.

43. Para 7 of the Circular provides that charges recovered from the borrowers by the REs on behalf of third-party service providers on actual basis shall also form part of the APR and has to be disclosed separately. So does this imply that any amount over and above the actuals will not form a part of APR?

In case the RE is collecting charges that are over and above the actuals, the same is int he form of charges levied by the RE itself and by default should always be included in the APR computation. However, in case of collection of charges on actuals on behalf third-party service provider, the RE shall be required to provide receipt and related documents will have to be provided to the borrower, within a reasonable time.

44. The KFS also needs to disclose the phone number and email id of the grievance redressal officer. So, will it be sufficient compliance with the regulations if a generic email id of the grievance redressal cell is provided ?

As per the KFS format provided, a generic email id and phone number can be provided by the RE in the KFS subject to the customer complaints being redressed within one working day.

45. The KFS must reveal whether the loan is currently or potentially subject to transfer to another RE entity or securitization. Therefore, if an RE fails to disclose this information while providing the KFS to the borrower, does it mean the RE is barred from transferring or securitizing the loan?

In case, the RE has revealed its intention to not transfer/securitise the loan but subsequently after disbursal intends to transfer/securitise the loan, it has to obtain the borrowers approval.

46. The Circular has prescribed that if the charges/fee payable cannot be determined prior to sanction, an upper ceiling may be prescribed by the RE. How will this upper ceiling be determined by the RE ?

The upper ceiling should be mentioned by the REs considering the maximum amount of charges that can be levied.

47. The Circular also extends to all HFCs. Henceforth, do HFCs solely need to furnish the KFS, or is there still an obligation to supply the MITC to borrowers as per the HFC directions?

The HFC directions require MITC to be provided to all borrowers for home loans. Additionally, the relevant provision of the HFC directions that mandates MITC provision has not been repealed. Therefore, until further regulatory clarity is provided on the subject, HFCs are obligated to furnish both MITC and KFS to borrowers.

48. What are the actionables for REs?

The immediate actionables for an RE shall be as follows:

Our other resources on the topic are:-

Watch our Webinar on the topic here:

– Team Finserv | finserv@vinodkothari.com

The Reserve Bank of India on 19th December 2023 issued a notification[1] imposing a bar on all regulated entities[2] (REs) with respect to their investments in AIFs. We had covered the same in our earlier write-up. The Circular has already created some bloodshed as several banks took a hit in their Q3 results. Though late, yet welcome, the RBI has now come with some relief by a March 27 2023 circular. The following Highlights are based on the original circular, as amended by the March 27th circular :-

Direct or indirect investments:

Investments through mutual funds and FOFs exempt:

Priority distribution model or structured AIFs

In our view, there is a need to review the regulatory mechanism for AIFs, as currently, AIFs are being used as instruments of regulatory arbitrage.

[1] https://rbi.org.in/Scripts/NotificationUser.aspx?Id=12572&Mode=0

[2] Commercial Banks (including Small Finance Banks, Local Area Banks and Regional Rural Banks), Primary (Urban) Co-operative Banks/State Co-operative Banks/ Central Co-operative Banks, All-India Financial Institutions, Non-Banking Financial Companies (including Housing Finance Companies)

Other articles related to the topic:

-Archisman Bhattacharjee I finserv@vinodkothari.com

Loading…

Loading…

– Vinod Kothari | finserv@vinodkothari.com

One of the most important, and often the most complicated issues in applying IndAS 109 to financial assets, particularly loan portfolios, is to the computation of expected credit losses (ECL). The following points need to be noted about ECL computation:

– Archisman Bhattacharjee & Kaushal Shah | finserv@vinodkothari.com

In order to harmonise the procedure of filing of regulatory returns across Supervised Entities (SEs) and create a single reference point, the RBI has issued Master Directions RBI (Filing of Supervisory Returns) Directions, 2024 (‘Returns Master Directions’) on February 27, 2024. As stated in the Statement on Developmental and Regulatory Policies dated August 10, 2023, these directions consolidate and harmonize instructions for filing supervisory/ regulatory returns.

The Returns Master Directions cover the following entities, collectively referred to as Supervised Entities (‘SEs’):

These Master Directions are effective immediately as on the date of notification (i.e. February 27, 2024).

Read more →– Anita Baid, finserv@vinodkothari.com

The recent RBI directive on streamlining the internal compliance monitoring function by leveraging technology has raised concerns regarding actionable on the part of regulated entities covered thereunder. The notification on Streamlining of Internal Compliance monitoring function – leveraging use of technology dated January 31, 2024 is based on RBI’s review of of the prevailing system in place for internal monitoring of compliance with regulatory instructions and the extent of usage of technological solutions to support this function.

Read more →| Register here: https://forms.gle/cQ3RYWAwhqd3hqTs7 |

Loading…

Loading…

Our resources on KYC can be accessed here.

Our resources on SBR:

Vinod Kothari, finserv@vinodkothari.com

Not sure if any cake was cut[1], but NBFC regulation turned 60, on 1st Feb., 2024. It was on 1st Feb., 1964 that the insertion of Chapter IIIB in the RBI Act was made effective. This is the chapter that gave the RBI statutory powers to register and regulate NBFCs.

What was the background to insertion of this regulatory power? Chapter IIIB was inserted by the Banking Law (Miscellaneous Provisions) Act, 1963. The text of the relevant Bill, 1963 gives the object of the amendment: “The existing enactments relating to banks do not provide for any control over companies or institutions, which, although they are not treated as banks, accept deposits from the general public or carry other business which is allied to banking. For ensuring more effective supervision and management of the monetary and credit system by the Reserve Bank, it is desirable that the Reserve Bank should be enabled to regulate the conditions on which deposits may be accepted by these non-banking companies or institutions. The Reserve Bank should also be empowered to give to any financial institution or institutions directions in respect of matters, in which the Reserve Bank, as the central banking institution of the country, may be interested from the point of view of the control of credit policy.”

Therefore, there were 2 major objectives – regulation of deposit-taking companies, and giving credit-creation connected directions, as these entities were engaged in quasi-banking activities.

Read more →