Banking exposure to open the current account by the banks

-Siddarth Goel (finserv@vinodkothari.com)

Background

Declaration from current account customers

The RBI issued a circular dated August 06, 2020, whereby the regulator instructed all scheduled commercial banks and payments banks shall not open a current account for customers who have availed credit facilities in form of cash credit (CC)/overdraft (OD) from the banking system. The motive behind the circular being that all the transactions of borrowers should be routed through the CC/OD account.

The genesis of this circular was in RBI circular dated May 15, 2004, where banks were advised that at the time of opening of current accounts for their customers, they have to insist on a declaration form by the account-holder to the effect that he is not enjoying any credit facility with any other bank or obtain a declaration giving particulars of credit facilities enjoyed by such customer. The move was in essence to secure the overall credit discipline in banking so that there is no diversion of funds by the borrowers to the detriment of the banking system. Post-May 15, 2004, a clarification notification was issued by the regulator dated August 04, 2004, stipulating that in case there is no response obtained concerning NOC after waiting a minimum period of a fortnight, the banks may open current accounts of the customers.

Thus there was an obligation on banks to scrupulously ensure that their branches do not open current accounts of entities that enjoy credit facilities (fund based or non-fund based) from the banking system without specifically obtaining a No-Objection Certificate (NOC) from the lending bank(s). Further, the non-adherence by banks as per the circular is to be perceived as abetting the siphoning of funds and such violations which are either reported to RBI or noticed during the regulator inspection would make the concerned banks liable for penalty under Banking Regulation Act.

Establishment of CRILC

The RBI established a Central Repository of Information on Large Credits (CRILC). The CRILC was established in connection to the RBI framework “Early Recognition of Financial Distress, Prompt Steps for Resolution and Fair Recovery for Lenders: Framework for Revitalising Distressed Assets in the Economy“. As under the framework banks were required to furnish credit information to CRILC on all their borrowers having aggregate fund-based and non-fund based exposure of Rs. 5 Crores and above with them. Besides banks were required to furnish current accounts of their customers with outstanding balance (debit or credit) of Rs 1 Crore and above to the CRILC. The reporting under the extant framework was to determine SMA-0 classification, where the principal or interest payment is not overdue for more than 30 days but account showing signs of stress. An increase in the frequency of overdrafts in current accounts is one of the illustrative methods for determining stress.

Reposting of large credits

Post establishment of CRILC, a subsequent guideline on the opening of current accounts by banks was issued by the RBI via circular dated July 02, 2015, dealing with the same subject. To enhance credit discipline, especially for the reduction in NPA level in banks, banks were asked to use the information available in CRILC and not limit their due diligence to seeking NOC. Banks were to verify from the data available in the CRILC database whether the customer is availing of credit facility from another bank.

The chart below highlights the series and events and relevant circulars.

Credit Discipline- August 06, 2020 Circular

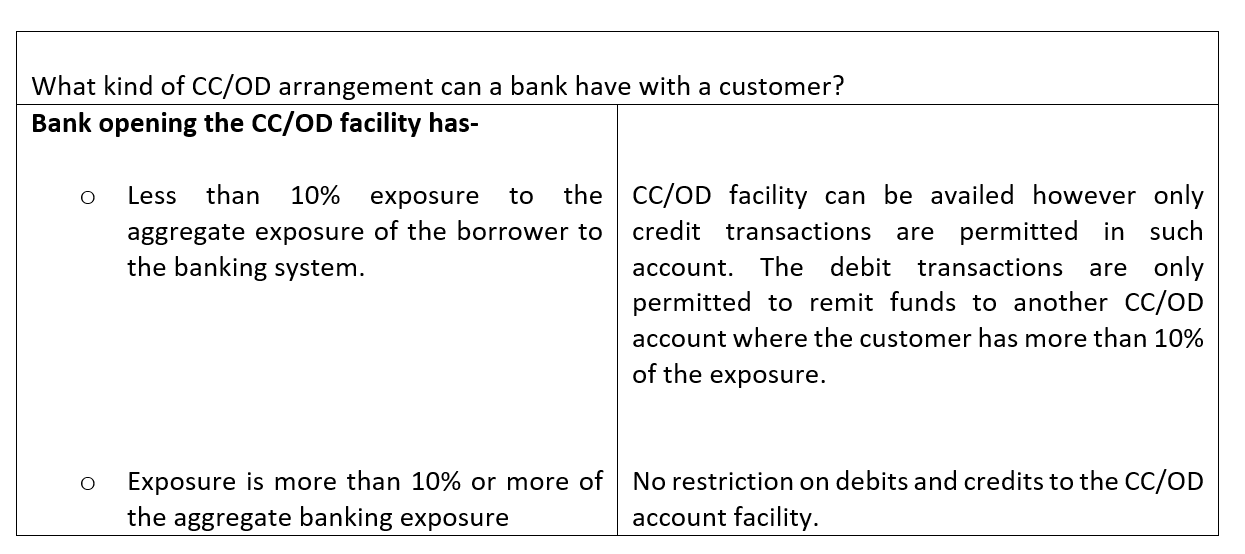

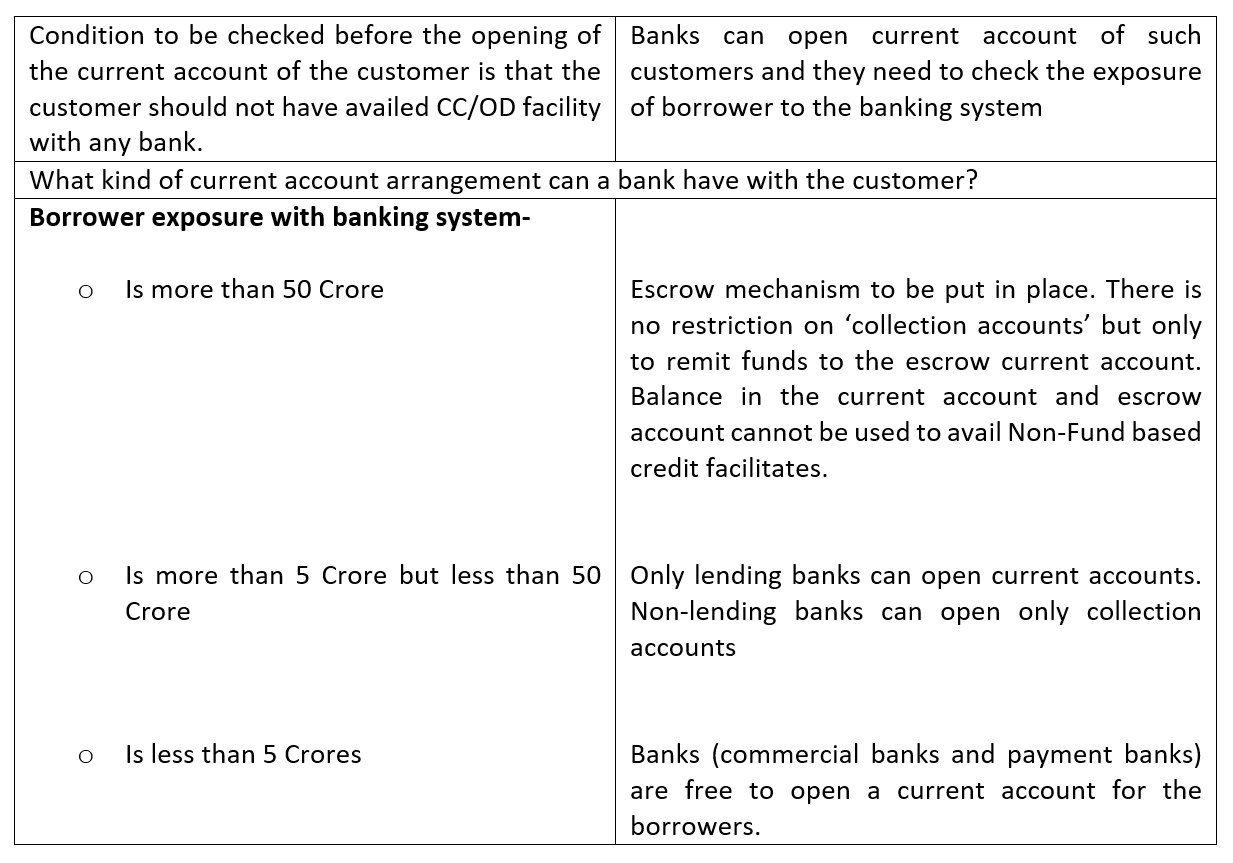

As per the circular dated August 06, 2020, issued by the regulator on Opening of Current Accounts by Banks – Need for Discipline (‘Revised Guidelines’), there are two aspects that need to be considered before opening a CC/OD facility or opening the current account of the customer. The Revised Guidelines provides a clear guiding flowchart for banks to follow when the customer approaches a bank for opening of the current account, the same has been categorised into two scenarios which could be considered by the banks to comply with the revised guideline.

Case 1: Customer wants to avail or is already having a credit facility in form of CC/OD

Case 2: Customer wants to open a current account or have an existing current account with the bank

Further, there is a requirement on banks to monitor all CC/OD accounts regularly at least quarterly, especially concerning the exposure of the banking system to the borrower. There has been an ambiguity surrounding what would amount to ‘exposure’ under the Revised Guidelines.

‘Exposure to the banking system’ under Revised Guidelines

The Revised Guidelines provides that exposure shall mean the sum of sanctioned ‘fund based and non-fund based credit facilities’. However, there is a regulatory ambiguity, since neither the term used by the RBI has been specifically defined in the Revised Guideline nor elsewhere under any other regulations. There is no straight jacket exclusive definition for determining as to what exposure banks should include determining funded and non-funded credit facilities. Therefore, based on back-tracing of regulatory regime an inclusive list can be of guidance for banks and borrowers especially large borrowers (like NBFCs and HFCs) and other financial institutions and corporates who rely on banking facilities (current account and CC/OD) extensively for their business.

The CRILC may not be the only source for banks while the collection of borrower’s credit information. Other modes could be information by Credit Information Companies (CICs), National E-Governance Services Ltd. (NeSL), etc., and even by obtaining customers’ declaration, if required. However, since the revised guideline stresses on borrowers having exposure more than 5 crores, therefore, information disseminated by the banks to CRILC is a good point to start with and to comply with under the revised guidelines. The circular dated July 02, 2015, draws reference to the Central Repository of Information on Large Credits (CRILC) to collect, store, and disseminate data on all borrowers’ credit exposures. The guideline further provided banks to verify the data available in the CRILC database whether the customer is availing credit facility from another bank. Further even under the Guidelines on “Early Recognition of Financial Distress, Prompt Steps for Resolution and Fair Recovery for Lenders” dated January 30, 2014, provided that credit information shall include all types of exposures as defined under RBI Circular on Exposure Norms.

The RBI Exposure Norms dated July 01, 2015, defines exposure as;

“Exposure shall include credit exposure (funded and non-funded credit limits) and investment exposure (including underwriting and similar commitments). The sanctioned limits or outstandings, whichever are higher, shall be reckoned for arriving at the exposure limit. However, in the case of fully drawn term loans, where there is no scope for re-drawal of any portion of the sanctioned limit, banks may reckon the outstanding as the exposure.”

The banking exposure norms provide for two exposures; namely credit and investment exposures. Further RBI Exposure Norms defines ‘credit exposure’ and ‘Investment Exposure’ as follows;

“2.1.3.3. Credit Exposure

Credit exposure comprises the following elements:

(a) all types of funded and non-funded credit limits.

(b) facilities extended by way of equipment leasing, hire purchase finance and factoring services.

2.1.3.4 Investment Exposure

- a) Investment exposure comprises the following elements:

(i) investments in shares and debentures of companies.

(ii) investment in PSU bonds

(iii) investments in Commercial Papers (CPs).

- b) Banks’ / FIs’ investments in debentures/ bonds / security receipts / pass-through certificates (PTCs) issued by an SC / RC as compensation consequent upon sale of financial assets will constitute exposure on the SC / RC. In view of the extraordinary nature of the event, banks / FIs will be allowed, in the initial years, to exceed the prudential exposure ceiling on a case-to-case basis.

- c) The investment made by the banks in bonds and debentures of corporates which are guaranteed by a PFI1(as per list given in Annex 1) will be treated as an exposure by the bank on the PFI and not on the corporate.

- d) Guarantees issued by the PFI to the bonds of corporates will be treated as an exposure by the PFI to the corporates to the extent of 50 per cent, being a non-fund facility, whereas the exposure of the bank on the PFI guaranteeing the corporate bond will be 100 per cent. The PFI before guaranteeing the bonds/debentures should, however, take into account the overall exposure of the guaranteed unit to the financial system.”

The Revised Guidelines, specifically define exposure in a footnote to the revised guideline stipulating that to arrive at aggregate exposures in the footnote as follows;

“‘Exposure’ for the purpose of these instructions shall mean sum of sanctioned fund based and non-fund based credit facilities”.

Further the RBI in its subsequent FAQs on revised guidelines dated December 14, 2020, guided on what could be included in aggregate exposure.

“4. Whether aggregate exposure shall include Day Light Over Draft (DLOD)/ intra-day facilities and irrevocable payment commitments, limits set up for transacting in FX and interest rate derivatives, CPs, etc.

All fund based and non-fund based credit facilities sanctioned by the banks and carried in their Indian books shall be included for the purpose of aggregate exposure.”

Further in FAQ No. 3 in the circular dated December 14, 2020, the RBI clarified that

“3. For the purpose of this circular, whether exposure of non-banking financial companies (NBFCs) and other financial institutions like National Housing Bank (NHB) shall be included in computing aggregate exposure of the banking system.

The instructions are applicable to Scheduled Commercial Banks and Payments Banks. Accordingly, the aggregate exposure for the purpose shall include exposures of these banks only”

While the regulator evaded assigning express meaning as to what could be included while determining banking exposure and took an inclusive view. However, from the foregoing, it is amply clear that the credit facilities should include credit exposures (funded and not funded) that have been sanctioned by banks. Therefore, only exposures to banks and payments banks are to be included while calculating exposures, any or all the exposure of a borrower to the other financial institutions like NHB, LIC Housing, SIDBI, NABARD, Mutual funds & other development Banks are neither commercial banks nor payments banks hence are to be excluded. [The list of licensed payments banks by the RBI can be viewed here. ]

CIRLC captures credit information of borrowers having aggregate fund-based and non-fund based exposures of Rs. 5 Crores and above including investment exposures. The banks are required to submit a quarterly return to CIRLC. It is pertinent to note that total investment exposure is to be indicated separately under the head total investment exposure. While there is a need for a detailed breakup on fund-based and non-fund based credit facilities in the CIRLC return. The table below is an indicative list of (funded and non-funded) loans to be submitted from the CIRLC return.

| Non-Funded credit exposure | Funded credit exposure |

| Letter of Credit | Cash Credit/ Overdraft |

| Guarantees | Working Capital Demand Loan (including CPs)* |

| Acceptances | Inland Bills |

| Foreign Exchange Contracts | Packing Credit |

| Interest Rate Derivatives (incl FX Interest Rate Derivatives) | Export Bills |

| Term Loan | |

| Credit equivalent of OBS/derivative exposure |

*CP to be included in WCDL only if part of working capital sanctioned limit. All other CPs are to be considered as investment exposure.

Therefore, all the investment exposures of banks to the borrower such as investments in corporate bonds, shares, PTCs issued by asset reconstruction companies and securitisation companies, and others are to be excluded while arriving at aggregate fund-based and non-fund based credit facilities as under the Revised Guidelines. Nevertheless, the PTCs issued by NBFCs or HFCs are investment exposure of banks on the underlying loan pools and not on the originator entity. Similarly, exposure of a bank in a co-lending transaction is exposure on the ultimate obligor and not the co-originating partner NBFC.

Our Other Related Articles

Banking Regulation (Amendment) Ordinance By Vallari Dubey – Vinod Kothari Consultants

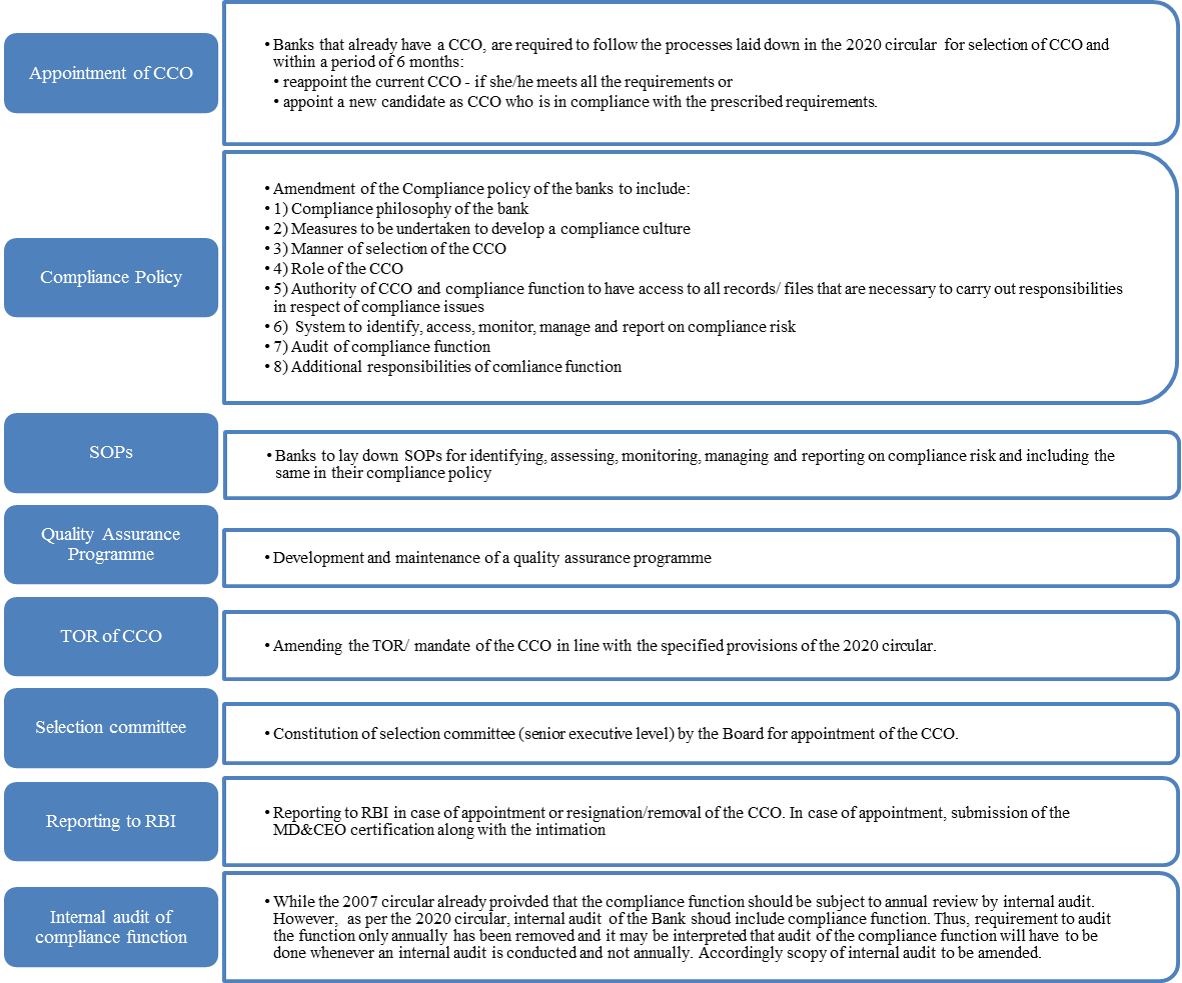

RBI guidelines on governance in commercial banks – Vinod Kothari Consultants

RBI proposes to strengthen governance in Banks – Vinod Kothari Consultants