By Sharon Pinto & Sachin Sharma, Corplaw division, Vinod Kothari & Company (corplaw@vinodkothari.com)

Background

The inception of the idea of Social Stock Exchanges (SSEs) in India can be traced to the mention of the formation of an SSE under the regulatory purview of Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI) for listing and raising of capital by social enterprises and voluntary organisations, in the 2019-20 Budget Speech of the Finance Minister. Consequently, SEBI constituted a working group on SSEs under the Chairmanship of Shri Ishaat Hussain on September 19, 2019[1]. The report of the Working Group (WG) set forth the framework on SSEs, shed light on the concept of social enterprises as well as the nature of instruments that can be raised under such framework and uniform reporting procedures. For further deliberations and refining of the process, SEBI set up a Technical Group (TG) under the Chairmanship of Dr. Harsh Kumar Bhanwala (Ex-Chairman, NABARD) on September 21, 2020[2]. The report, made public on May 6, 2021[3], of the TG entails qualifying criteria as well as the exhaustive ecosystem in which such an SSE would function.

In this article we have analysed the framework set forth by the reports of the committees with the globally established practices.

Concept of SSEs

As per the report of the WG dated June 1, 2020[4], SSE is not only a place where securities or other funding structures are “listed” but also a set of procedures that act as a filter, selecting-in only those entities that are creating measurable social impact and reporting such impact. Further the SSE shall be a separate segment under the existing stock exchanges. Thus, an SSE provides the infrastructure for listing and disclosure of information of listed social enterprises.

Such a framework has been implemented in various countries and an analysis of the same can be set forth as follows:

A. United Kingdom

- The Social Stock Exchange (SSX) was formed in June 2013 on the recommendation of the report of Social Investment Taskforce. The exchange does not yet facilitate share trading, but instead serves as a directory of companies that have passed a ‘social impact test’. It thus provides a detailed database of companies which have social businesses. It facilitates as a research service for potential social impact investors.

- Further, companies that are trading publically in the main board stock exchange, may list their securities on SSX, thus only for-profit companies can list on the SSX[5] It works with the support of the London Stock Exchange and is a standalone body not regulated by any official entity.

- Social and environment impact is the core aim of SSX. To satisfy the same, companies are required to submit a Social Impact Report for review by the independent Admissions Panel composed of 11 finance and impact investing experts.

- The disclosure framework comprises adherence to UK Corporate Governance Guidelines and Filing Annual Social Impact Reports determine the continuation of listing in SSX.

B. Canada

- Social Venture Connection (SVX)[6] was launched in 2013. Like SSX, SVX is not an actual trading platform but it is a private investment platform built to connect impact ventures, funds, and investors. It is open only for institutional investors[7].

- The platform facilitates listing of for-profit business, NPO, or cooperatives categorized as, Social Impact Issuers and Environment Impact Issuers. These entities are required to be incorporated in Ontario for at least 2 years and have audited financial statements available.

- For listing, a for-profit business must obtain satisfactory company ratings through GIIRS, a privately administered rating system.

- Issuer must conform to the SVX Issuer Manual. In addition to this reporting of expenditure and other financial transactions shall be done once capital is raised. Further the issuers are required to file financial statements annually in accepted accounting methods and shall not have any misleading information. Ratings are required to be obtained, however the provisions are silent on the periodicity of revision of ratings.

C. Singapore

- Singapore has established Impact Exchange (IX) which is operated by Stock Exchange of Mauritius and regulated by the Financial Service Commission of Mauritius.

- IX is the only SSE that is an actual public exchange. It is thus a public trading platform dedicated to connecting social enterprise with mission-aligned investment. Social enterprises, both for-profits and non-profits, are permitted to list their project. NGOs are allowed as issuers of debt securities (such as bonds).

- Listing requirements on the exchange are enumerated into social and financial categories. Following comprise the social criteria for listing:

- Specify social or economic impact as the reason for their primary existence.

- Articulate the purpose and intent of the company in the form of a theory of change- basis for demonstrating social performance.

- Commit to ongoing monitoring and evaluation of impact performance assessment and reporting.

- Minimum 1 year of impact reports prepared as per IX reporting principles.

- Certification of impact reports by an independent rating body 12 months prior listing.

Further the financial criteria entails the need for a fixed limit of minimum market capitalization, publication of financial statements and use of market-based approach for achieving its purpose.

D. South Africa

- The ‘South Africa Social Exchange’ or SASIX[8], offers ethical investors a platform to buy shares in social projects according to two classifications: by sector and by province[9]. Guidelines for listing prescribe compliance with SASIX’s good practice norms for each sector.

- In order to get listed, entities have to achieve a measurable social impact. The platform acts as a tool of research, evaluation and match-making to facilitate investments into social development projects

- NGOs can also list their social projects on the exchange. Value of the projects is assessed and then divided into shares. Following project implementation, investors are given access to financial and social reports.

- While social enterprises are required to have a social purpose as their primary aim, they are also expected to have a financially sustainable business model. The SASIX ceased functioning in 2017[10].

Key ingredients for a social enterprise

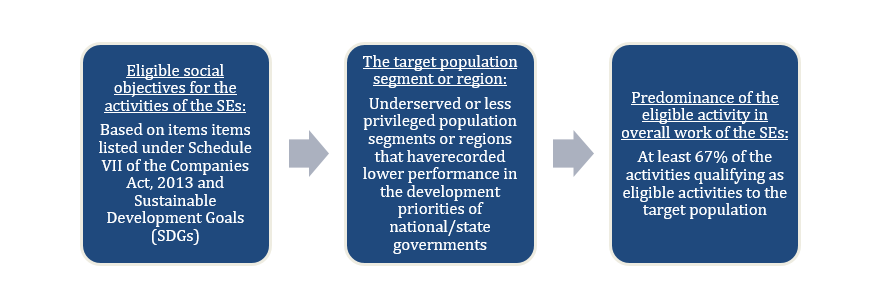

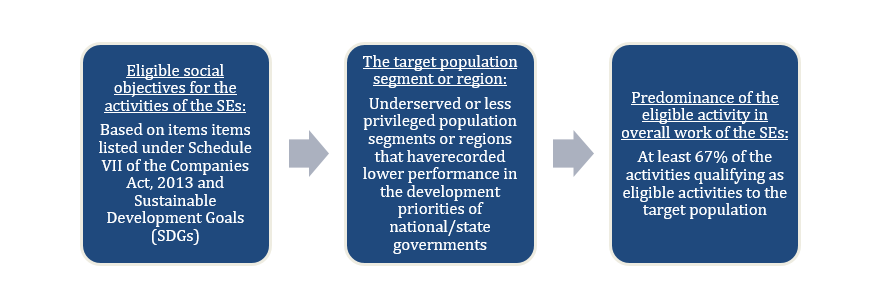

- The report of the TG[11] has categorised social enterprises into For Profit Enterprise (FPEs) and Not for Profit Organisation (NPOs). In order to qualify as a social enterprise the entities shall establish primacy of social impact which shall be determined by application of the following 3 filters:

- On establishment of the primacy of social impact through the three filters as stated above, the entity shall be eligible to qualify for on-boarding the SSE and access to the SSE for fund-raising upon submitting a declaration as prescribed.

Qualifying criteria and process for onboarding

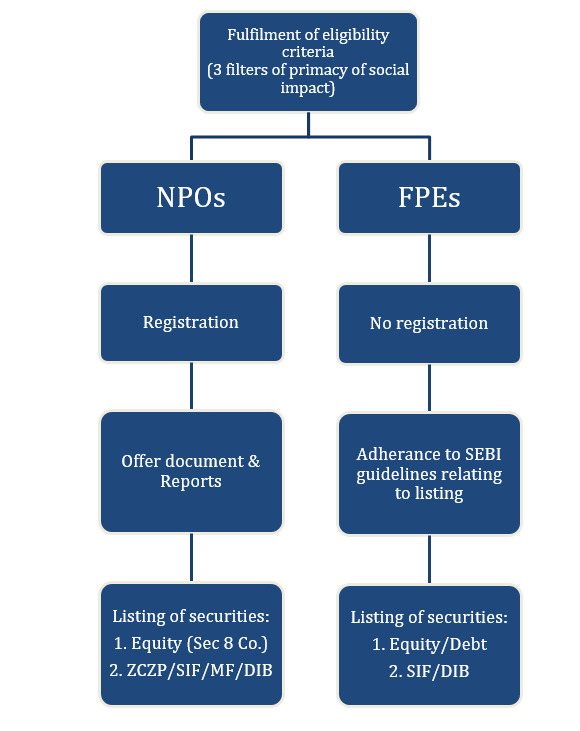

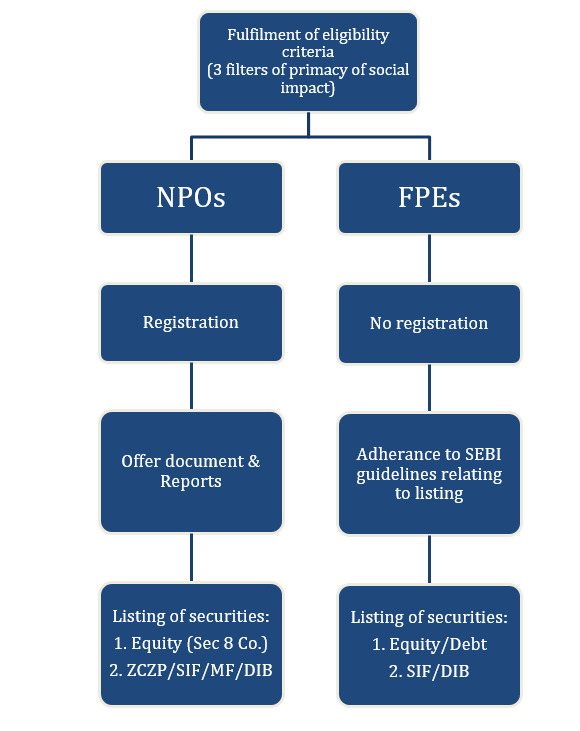

As per TG recommendation, an NPO is required to register on any of the Social Stock Exchange and thereafter, it may choose to list or not. However, an FPE can proceed directly for listing, provided it is a company registered under Companies Act and complies with the requirements in terms of SEBI Regulations for issuance and listing of equity or debt securities.

Further, the TG has recommended a set of mandatory criteria as mentioned below that NPOs shall meet in order to register.

A. Legal Requirements:

- Entity is legally registered as an NPO (Charitable Trust/ Society/Section-8 Co’s).

- Shall have governing documents (MoA & AoA/ Trust Deed/ Bye-laws/ Constitution) & Disclose whether owned and/or controlled by government or private.

- Shall have Registration Certificate under 12A/12AA/12AB under Income Tax.

- Shall have a valid IT PAN.

- Shall have a Registration Certificate of minimum 3 years of its existence.

- Shall have valid 80G registration under Income-Tax.

B. Minimum Fund Flows:

In order to ensure that the NPO wishing to register has an adequate track-record of operations.

- Receipts or payments from Audited accounts/ Fund Flow Statement in the last financial year must be at least Rs. 50 lakhs.

- Receipts from Audited accounts/ Fund Flow Statement in the last financial year must be at least Rs. 10 lakhs.

Framework for listing

Post establishment of the eligibility for listing and the additional registration criteria in case of NPOs, the social enterprises may list their securities in the manner discussed further. The listing procedures vary for NPOs and FPEs and is set forth as follows:

A. NPOs

- NPO shall be required to provide audited financial statements for the previous 3 years and social impact statements in the format prescribed. Further the offer document shall comprise of ‘differentiators’ which shall help the potential investors to assess the NPOs being listed and form a sound and well-informed investment decision. A list of 11 such differentiators has been provided in the report of the TG.

- Further in case of program-specific or project-specific listings, the NPO shall have to provide a greater level of detail in the listing document about its track record and impact created in the program target segment.

- All the information submitted as part of pre-listing and post-listing requirements, shall be duly displayed on the website of the NPO.

B. FPEs

- In case of an FPE, existing regulatory guidelines under various SEBI Regulations for listing securities such as equity, debt shall be complied with.

- The differentiators will be in addition to requirements as mandated in SEBI Regulations in respect of raising funds through equity or debt.

- Further, FPEs have been granted an option to list their securities on the appropriate existing boards. Thus the issuer may at their discretion list their debt securities on the main boards, while equity securities may be listed on the main boards, or on the SME or IGP.

Types of instruments

Depending on the type of organisation, SSEs shall allow a variety of financing instruments for NPOs and FPEs. As FPEs have already well-established instruments, these securities are permitted to be listed on the Main Board/IGP/SME, however visibility shall be given to such entities by identifying them as For Profit Social Enterprise (FPSE) on the respective stock exchanges.

Modes available for fundraising for NPOs shall be Equity (Section 8 Co’s.), Zero Coupon Zero Principal (ZCZP) bonds [this will have to be notified as a security under Securities Contracts (Regulation) Act, 1956 (SCRA)], Development Impact Bonds (DIB), Social Impact Fund (SIF) (currently known as Social Venture Fund) with 100% grants-in grants out provision and funding by investors through Mutual Funds. On the other hand, FPEs shall be able to raise funds through equity, debt, DIBs and SIFs.

While SVF is an existing model for fund-raising, the TG has proposed various changes in order to incentivise investors and philanthropists to invest in such instruments. In addition to change in nomenclature from SVF to SIF, minimum corpus size is proposed to be reduced from Rs. 20 Cr to Rs. 5 Cr. Further, minimum subscription shall stand at Rs. 2L from the current Rs. 1 Cr. The amendments shall also allow corporates to invest CSR funds into SVFs with a 100% grants-in, grants out model.

Disclosure and Reporting norms

Once the FPE or the NPO (registered/listed) has been demarcated by the exchange to be an SE, it needs to comply with a set of minimum disclosure and reporting requirements to continue to remain listed/registered. The disclosure requirements can be enlisted as follows:

For NPO:

- NPO’s (either registered or listed) will have to disclose on general, governance and financial aspects on an annual basis.

- The disclosures will include vision, mission, activities, scale of operations, board and management, related party transactions, remuneration policies, stakeholder redressal, balance sheet, income statement, program-wise fund utilization for the year, auditors report etc.

- NPO’s will have to report within 7 days any event that might have a material impact on the planned achievement of their outputs or outcomes, to the exchange in which they are registered/listed. This disclosure will include details of the event, the potential impact and what the NPO is doing to overcome the impact.

- NPO”s that have listed its securities will have to disclose Social Impact Report covering aspects such as strategic intent and planning, approach, impact score card etc. on annual basis.

For FPE:

FPE’s having listed equity/debt will have to disclose Social Impact Report on annual basis and comply with the disclosure requirements as per the applicable segment such as main board, SME, IGP etc.

Other factors of the SSE ecosystem

a. Capacity Building Fund

As per the recommendation of the WG, constitution of a Capacity Building Fund (CBF) has been proposed. The said fund shall be housed under NABARD and funded by Stock Exchanges, other developmental agencies such as SIDBI, other financial institutions, and donors (CSRs). The fund shall have a corpus of Rs. 100 Cr and shall be an entity registered under 80G, which shall make it eligible for receiving CSR donations pursuant to changes to Section 135/Schedule VII of Companies Act 2013. The role of the fund shall encompass facilitating NPOs for registration and listing procedures as well as proper reporting framework. These functions shall be carried out in the form awareness programs.

b. Social Auditors

Social audit of the enterprises shall compose of two components – financial audit and non-financial audit, which shall be carried out by financial or non-financial auditors. In addition to holding a certificate of practice from the Institute of Chartered Accountants of India (ICAI), the auditors will be required to have attended a course at the National Institute of Securities Markets (NISM) and received a certificate of completion after successfully passing the course examination. The SRO shall prepare the criteria and list of firms/institutions for the first phase soon after the formation of SSEs, and those firms/institutions shall register with the SRO.

c. Information Repositories

The platform shall function as a research tool for the various social enterprises to be listed, thus Information Repository (IR) forms an important component of the framework. It functions as an aggregator of information on NGOs, and provides a searchable electronic database in a comparable form. Thus it shall provide accurate, timely, reliable information required by the potential investors to make well informed decisions.

Conclusion

The social sector in India is getting increasingly powerful – this was evident during Covid-crisis based on the wonderful work done by several NGOs. Of course, all social work requires funding, and being able to crowd source funding in a legitimate and transparent manner is quintessential for the social sector. We find the report of the TG to be raising and addressing relevant issues. We are hoping that SEBI will now find it easy to come out with the needed regulatory platform to allow social enterprises to get funding through SSEs.

Our other article on the similar topic can be read here – http://vinodkothari.com/2019/09/social-stock-exchange-a-guide/

[1] https://www.sebi.gov.in/media/press-releases/sep-2019/sebi-constitutes-working-group-on-social-stock-exchanges-sse-_44311.html

[2] https://www.sebi.gov.in/media/press-releases/sep-2020/sebi-constitutes-technical-group-on-social-stock-exchange_47607.html

[3] https://www.sebi.gov.in/reports-and-statistics/reports/may-2021/technical-group-report-on-social-stock-exchange_50071.html

[4] https://www.sebi.gov.in/reports-and-statistics/reports/jun-2020/report-of-the-working-group-on-social-stock-exchange_46852.html

[5] https://scholarship.law.upenn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1906&context=jil&httpsredir=1&referer=

[6] https://www.svx.ca/faq

[7] https://ssir.org/articles/entry/the_rise_of_social_stock_exchanges

[8] https://www.sasix.co.za/

[9] https://ssir.org/articles/entry/the_rise_of_social_stock_exchanges

[10] https://www.samhita.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/India-SSE-report-final.pdf

[11] https://www.sebi.gov.in/reports-and-statistics/reports/may-2021/technical-group-report-on-social-stock-exchange_50071.html