Indian Securitisation Market opens big in FY 20 – A performance review and a diagnosis of the inherent problems in the market

/1 Comment/in Capital Markets, Financial Services, News on Securitization, Securitisation /by Vinod Kothari ConsultantsBy Abhirup Ghosh , (abhirup@vinodkothari.com)(finserv@vinodkothari.com)

Ever since the liquidity crisis crept in the financial sector, securitisation and direct assignment transactions have become the main stay fund raising methods for the financial sector entities. This is mainly because of the growing reluctance of the banks in taking direct exposure on the NBFCs, especially after the episodes of IL&FS, DHFL etc.

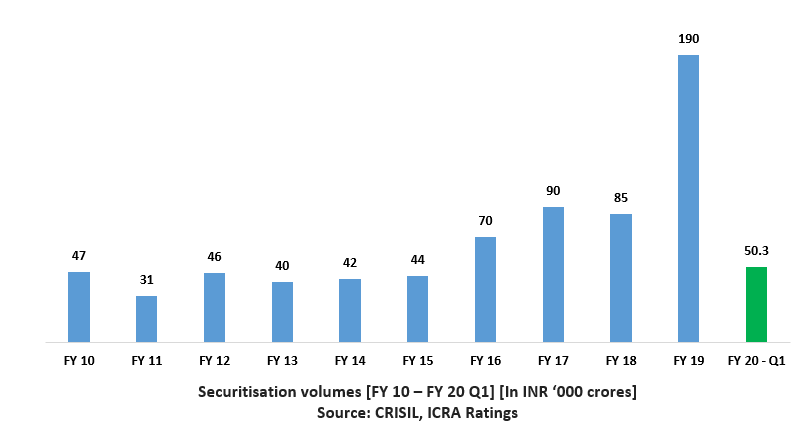

Resultantly, the transactions have witnessed unprecedented growth. For instance, the volume of transactions in the first quarter of the current financial year stood at a record ₹ 50,300 crores[1] which grew at 56% on y-o-y basis from ₹ 32,300 crores. Segment-wise, the securitisation transactions grew by whooping 95% to ₹ 22,000 crores as against ₹ 11,300 crores a year back. The volume of direct assignments also grew by 35% to ₹ 28,300 crores as against ₹ 21,000 crores a year back.

The chart below show the performance of the industry in the past few years:

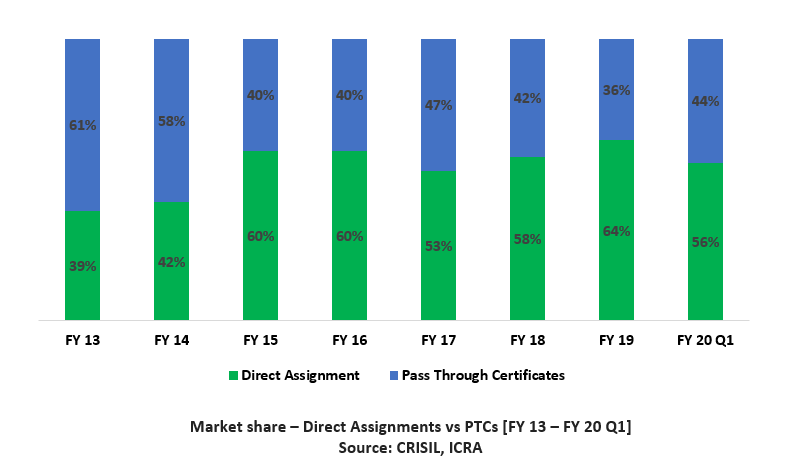

Direct Assignments have been dominating market with the majority share. During Q1 FY 20, DAs constituted roughly 56% of the total market and PTCs filled up the rest. The chart below shows historical statistics about the share of DA and PTCs:

In terms of asset classes, non-mortgage asset classes continue to dominate the market, especially vehicle loans. The table below shows the share of the different asset classes of PTCs:

|

Asset class |

Q1 FY 20 share | Q1 FY 19 share | FY 19 share |

| Vehicle (CV, CE, Car) | 51% | 57% | 49% |

| Mortgages (Home Loan & LAP) | 20% | 0% | 10% |

| Tractor | 6% | 0% | 10% |

| MSME | 5% | 1% | 4% |

| Micro Loans | 4% | 23% | 16% |

| Lease Rentals | 0% | 13% | 17% |

| Others | 14% | 6% | 1% |

Asset class wise share of PTCs

Source: ICRA

Shortcomings in the current securitisation structures

Having talked about the exemplary performance, let us now focus on the potential threats in the market. A securitisation transaction becomes fool proof only when the transaction achieves bankruptcy-remoteness, that is, when all the originator’s bankruptcy related risks are detached from the securitised assets. However, the way the current transactions are structured, the very bankruptcy-remoteness of the transactions has become questionable. Each of the problems have been discussed separately below:

Commingling risk

In most of the current structures, the servicing of the cash flows is carried out of the originator itself. The collections are made as per either of the following methods:

- Cash Collection – This is the most common method of repayment in case of micro finance and small ticket size loans, where the instalments are paid in cash. Either the collection agent of the lender goes to the borrower for collecting the cash repayments or the borrower deposits the cash directly into the bank account of the lender or at the registered office or branch of the lender.

- Encashment of post-dated cheques (PDCs) – The PDCs are taken from the borrower at the inception of the credit facility for the EMIs and as security.

- Transfer through RTGS/NEFT by the customer to the originator’s bank account.

- NACH debit mandate or standing instructions.

In all of the aforesaid cases, the payment flows into the current/ business account of the originator. The moment the cash flows fall in the originator’s current account, they get exposed to commingling risk. In such a case, if the originator goes into bankruptcy, there could be serious concerns regarding the recoverability of the cash flows collected by the originator but not paid to the investors. Also, because redirection of cash flows upon such an event will be extremely difficult to implement. Therefore, in case of exigencies like the bankruptcy of the originator, even an AAA-rated security can become trash overnight. This brings up a very important question on whether AAA-PTCs are truly AAA or not.

This issue can be addressed if, going forward, the originators originate only such transactions in which repayments are to happen through NACH mandates. NACH mandates are executed in favour of third party service providers which triggers direct debit from the bank account of the customers every month against the instalments due. Upon receipt of the money from the customer, the third party service providers then transfer the amount received to the originators. Since, the mandates are originally executed in the name of the third party service providers and not on the originators, the payments can easily be redirected in favour of the securitisation trusts in case the originator goes into bankruptcy. The ease of redirection of cash flows NACH mechanism provides is not available in any other ways of fund transfer, referred above.

Will the assets form part of the liquidation estate of the lessor, since under IndAS the assets continue to get reflected on Balance Sheet of the originator?

With the implementation of Ind AS in financial sector, most of the securitisation transactions are failing to fulfil the complex de-recognition criteria laid down in Ind AS 109. Resultantly, the receivables continue to stay on the books of the originator despite a legal true sale of the same. Due to this a new concern has surfaced in the industry that is, whether the assets, despite being on the books of the originator, be absolved from the liquidation estate of the originator in case the same goes into liquidation.

Under the current framework for bankruptcy of corporates in India, the confines of liquidation estate are laid in section 36 of the IBC. Section 36 (3) lays what all will be included therein. Primarily, section 36 (3) (a) is the relevant provision, saying “any assets over which the corporate debtor has ownership rights” will be included in the estate. There is a reference to the balance sheet, but the balance sheet is merely an evidence of the ownership rights. The ownership rights are a matter of contract and in case of receivables securitised, the ownership is transferred to the SPV.

The bounds of liquidation estate are fixed by the contractual rights over the asset. Contractually, the originator has transferred, by way of true sale, the receivables. The continuing balance sheet recognition has no bearing on the transfer of the receivables. Therefore, even if the originator goes into liquidation, the securitised assets will remain unaffected.

Conclusion

Despite the shortcomings in the current structures, the Indian market has opened big. After the market posted its highest volumes in the year before, several industry experts doubted whether the market will be able to out-do its previous record or for that matter even reach closer to what it has achieved. But after a brilliant start this year, it seems the dream run of the Indian securitisation industry has not ended yet.

[1] https://www.icra.in/Media/OpenMedia?Key=94261612-a1ce-467b-9e5d-4bc758367220

Private virtual currencies out: India may soon see regulated virtual currency

/0 Comments/in Capital Markets, Financial Services, Fintechs and Payment and Settlement Systems /by Vinod Kothari Consultants-Kanakprabha Jethani | executive

kanak@vinodkothari.com

Background

A high-level Inter-ministerial Committee (IMC) (‘Committee’) was constituted under the chairmanship of Secretary, Department of Economic Affairs (DEA) to study the issues related to Virtual Currencies (VCs) and propose specific action to be taken in this matter. The Committee came up with its recommendations[1] recently. These recommendations include, among other things, ban on private VCs, examination of technologies underlying VCs and their impact on financial system, viability of issue of ‘Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC)’ as legal tender in India, and potential of digital currency in the near future.

The following write-up deals with an all-round study of the recommendations of the committee and their probable impacts on the financial systems and the economy as a whole.

Major recommendations of the Committee.

The report of the Committee focuses on Distributed Ledger Technologies (DLT) or blockchain technology and their use to facilitate transactions in VCs and their relation to financial system. Following are the major recommendations of the Committee.

- DEA should identify uses of DLT and various regulators should focus on developing appropriate regulations regarding use of DLT in their respective areas.

- All private cryptocurrencies should be banned in India.

- Introduction of an official digital currency to be known as Central bank digital currency (CBDC) which shall be acceptable as legal tender in India.

- Blockchain based systems may be considered by Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology (MEITY) for building low-cost KYC systems.

- DLT may be used for collection of stamp duty in the existing e-stamping system.

Why were these recommendations needed?

- DLT uses independent computers (called ‘nodes’), linked together through hash function, to record, share and synchronise transactions in their respective distributed ledgers. The detailed structure of DLTs and their functions and uses can be referred to in our other articles.[2]

Among its various benefits such as data security, privacy, permanent data retention, this system addresses one major issue linked to digital currency which is the problem of double-spend i.e. a digital currency can be spent more than once as digital data can be easily reproduced. In DLT, authenticity of a transaction can be verified by the user and only validated transactions form a block under this mechanism.

- Many companies have been using Initial Coin Offerings (ICO) as a medium to raise money by issuing digital tokens in exchange of fiat money or a widely accepted cryptocurrency. This way of raising money has been bothering regulators as it has no regulatory backing and such system can collapse any time. The regulators also fail to reckon whether ICO can be even considered as a security or how it should be taxed.

- Some countries allow use of VCs as a mode of payment but no country in the world accepts VCs as legal tender. In India, however, no such permissions are granted to VCs. Despite the non-acceptability of VCs in India, investors have been actively investing in VCs like bitcoin, which is a sign of danger for the economy as it is draining the financial systems of fiat money. Further, they pose a risk over the financial system as they are highly volatile, with no sovereign backing and no regulators to oversee. It has been witnessed in the recent years that there have been detrimental implications on the economy due to volatility of VCs such as bitcoins. the same has been dealt with in detail in our report[3] on Bitcoins. They are also suspected to have been facilitating criminal activities by providing anonymity to the transactions as well as to the persons involved.

- The future is of digitisation. An economy with everything running on physical basis will not survive in the competitive world. A universally accepted system for digital payments would require digitisation of currency as well.

What is the regulatory philosophy in the world?

As a mode of payment: Countries like Switzerland, Thailand, Japan and Canada permit VCs as a mode of payment while New York requires persons using VCs to take prior registration with a specified authority. Russia allows only barter exchange through use of virtual currency which means that such exchange can only take place when routed through barter exchanges of Russia. China prohibits use of VCs as a mode of payment.

For investment purposes: Russia, Switzerland, Thailand, New York and Canada permit investment in VCs and have in place frameworks to regulate such investments. Further, countries like Russia, Thailand, japan, New York and Canada have also allowed setting up of crypto exchanges and have a framework for regulating the setting up and operations such exchange and subsequent trading of VCs on them. On the other hand, China altogether prohibits investments and trading in VCs and the law of Switzerland is silent as to allowing setting up of crypto exchanges.

Further, China has imposed a strict ban on any activity in cryptocurrencies and has also taken measures to prohibit crypto mining activities in its jurisdiction. No country in the world has allowed acceptance of virtual currency as legal tender. It is noteworthy that though Japan and Thailand allow transactions in VCs, such transactions are restricted to approved cryptocurrencies only.

Tunisia and Ecuador have issued their own blockchain based currency called eDinar and SISTEMA de Dinero Electronico respectively. Venezuela has also launched an oil-based cryptocurrency.

Issue of official digital currency

Sensing the keen inclination of financial systems towards technological innovation and witnessing declining use of physical currency in various countries, the Committee is of the view that a sovereign backed digital currency is required to be issued which will be treated at par with any other legal tender of the country.

Various legislations of the country need to be reviewed in this direction. This would include amendments to the definition of “Coin” as per Coinage Act for clarifying whether digital currency issued by RBI shall be included in the said definition. Further, on issue of such currency, it must be approved to be a “bank note” as per section 25 of RBI Act through notification in Gazette of India.

Various regulators would also be required to amend their respective regulations to align them in the direction of allowing use of such digital currency as an accepted form of currency.

Key features of CBDC are expected to be as follows:

- The access to CBDC will be subject to time constraints as decided in the framework regulating the same.

- CBDC will be designed to provide anonymity in the transaction. However, the extent of anonymity will depend on the decisions of the issuing authority.

- Two models are under consideration for defining transfer mechanism for CBDC. One is account-based model which will be centralised and other one is value-based model which will be decentralised model. Hybrid variants may also be considered in this regard.

- Contemplations as to have interest-bearing or non-interest-bearing CBDC are going on. An interest-bearing CBDC would allow value addition whereas non-interest bearing CBDC will operate as cash.

Why should DLT be used in financial systems?

- Intermediation: Usually, in payment systems, there are layers of intermediation that add to cost of transaction. Through DLT, the transaction will be executed directly between the nodes with no intermediary which would then reduce the transaction costs. Further, in cross-border transactions through intermediaries, authorisations require a lot of time and result in slow down of transaction. This can also be done away through DLT.

- KYC: Keeping KYC records and maintaining the same requires huge amounts of data to be stored and updated regularly. Various entities undergoing the same KYC processes, collecting the same proofs of identity from the same person for different transactions result in duplication of work. Through a blockchain based KYC record, the same record can be made available to various entities at once, while also ensuring privacy of data as no centralised entity will be involved. Loan appraisal: A blockchain technology can largely reduce the burden of due-diligence of loan applicant as the data of customers’ earlier loan transactions is readily available and their credit standing can be determined through that.

- Trading: In trading, blockchain based systems can result in real-time settlement of transactions rather than T+2 settlement system as prevailing under the existing stock exchange mechanism. Since all the transactions are properly recorded, it provides an easier way of post-trade regulatory reporting.

- Land registries and property titles: A robust land registry system can be established through use of blockchain mechanism which will have the complete history of ownership records and other rights relating to the property which would facilitate transfer of property as well as rights related to it.

- E-stamping: A blockchain based system would ease out the process of updation of records across various authorities involved and would eliminate the need of having a central agency for keeping records of transaction.

- Financial service providers: They can be benefited by the concept of ‘localisation of data’ due to which their data is protected from cyber-attacks and theft. Our article[4] studies implementation of blockchain technology in financial sector.

What will be the challenges?

- For implementation of DLT: Though a wide range of benefits can be reaped out of implementation of DLT in various aspects of financial systems, it has still not been implemented because there are a few hindrances that remain and are expected to continue even further. Some of the challenges that are slowing the pace of transition towards this technology are as follows:

- Lack of technological equipment to handle volumes of transactions on blockchains and to ensure data security at the same time.

- Absence of centralised infrastructure or central entity to regulate implementation of DLT in the financial system. Also, the existing regulators lack the expertise to oversee proper implementation.

- First, a comprehensive regulatory framework needs to be in place that ensures governance in implementation. The framework will need to address concerns like jurisdiction in case of cross border ledgers, point of finality of transactions etc.

- For common digital currency: Decisions regarding validation function, settlement, transfer, value-addition etc. are of crucial importance and would require extensive study. Factors that might be hampering issue of such currency are as follows:

- Having in place a safe and secure blockchain network and robust technology to handle the same will require significant investments.

- High volumes of transactions may not be supported and might result in delays in processing.

- In case an interest bearing CBDC is issued, it would pose great threat over the commercial banking system as the investors will be more inclined towards investing in CBDCs instead of bank deposits.

- This is also likely to increase competition in the market and lower the profitability of commercial banks. Commercial banks may rely on overseas wholesale funding which might result in downturn of such banks in overseas market.

- For banning of private cryptocurrencies: A circular issued by the RBI has already banned its regulated entities from dealing in VCs. Many other countries have also banned dealing in VCs. Despite such restrictions, entities continue to deal in VCs because their speculative motives drive the dealing in VCs to a great extent.

Conclusion

The recommendations of the Committee intend to ensure safety of financial systems and simultaneously urge the growth of the system through innovation and technological advances. Rising above the glorious scenes of these recommendations, one realises that achieving this is a far-fetched reality. One needs to accept the fact that India still lacks in technology and systems sufficient to support innovations like blockchain. Various reports have already shown that operation of blockchains consumes huge volumes of energy, which can be the biggest issue for the energy-scarce India. India needs to work in order to strengthen its core before flapping its wings towards such sophisticated innovation.

[1] https://dea.gov.in/sites/default/files/Approved%20and%20Signed%20Report%20and%20Bill%20of%20IMC%20on%20VCs%2028%20Feb%202019.pdf

[2] http://vinodkothari.com/2019/06/blockchain-technology-its-applications-in-financial-sector/

http://vinodkothari.com/2019/06/an-introduction-to-smart-contracts-guest-post/

[3] http://vinodkothari.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/Bitcoints-India-Report.pdf

[4] http://vinodkothari.com/2019/07/blockchain-based-lending-a-peer-to-peer-approach/

Distinguishing between Options and Forwards

/0 Comments/in Capital Markets, Corporate Laws, UPDATES /by Vinod Kothari ConsultantsBy Falak Dutta (rajeev@vinodkothari.com)

Ruling of Bombay High Court

The Bombay High Court on March 27, 2019, in the case of Edelweiss Financial Services v. Percept Finserve Pvt. Ltd.[1], ruled out an award passed by a sole arbitrator with respect to a share purchase agreement (SPA). The High Court allowed enforcing of a put option clause to be exercised by Edelweiss, the appellant, to sell back the shares it had acquired from Percept Group, the respondent.

Before delving into the proceedings of the aforesaid case, it is important to understand certain basic concepts, to appreciate the ‘option clause’ in the case. An option is a derivative contract which gives the holder the right but not the obligation to buy (call) or sell (put) the underlying within a stipulated time in exchange for a premium. Options are not just traded on exchanges but are also used in debt instruments (eg. callable and puttable bonds), private equity and venture capital investment covenants. Even insurance is a type of option contract where the insured pays monthly premium in exchange of a monetary claim upon the future occurrence of a contingent event (accident, disease, damage to property etc.).

Facts of the case

Edelweiss Financial Services Pvt. Ltd. entered into a share purchase agreement (SPA) dated 8, December, 2007 with the Percept Group where it invested in the shares of Percept Group subject to a condition that the latter shall restructure itself as agreed between the parties followed by an IPO. Under the terms of the SPA, the appellant (Edelweiss) purchased 228,374 shares for a consideration of Rs. 20 crores. One of the conditions in the agreement, required Percept to entirely restructure by 31st December, 2007 and to provide proof of such restructuring. Upon failure of compliance by the respondent, the date was further extended to 30 June, 2008 with obligation to provide documentary evidence of completion by 15th, July 2008. Upon non-fulfillment within the extended date, Edelweiss had the option to re-sell the shares to Percept, where Percept was obligated to purchase the shares at a price which gave the appellant an internal rate of return of 10% on the original purchase price.

As was the case, Percept failed to restructure itself within the stipulated time. Subsequently in view of this breach Edelweiss exercised the put option and Percept was required to buy back the shares for a total consideration of Rs. 22 crores. Since the respondent refused to comply the appellant invoked the arbitration clause in the SPA and a sole arbitrator was appointed to adjudicate the dispute. The arbitrator submitted that despite Percept being in breach of the conditions in the SPA, the petitioner’s claim to exercise the put option was illegal and unenforceable, being in conflict with the Securities Contracts regulation Act (SCRA), 1956. The unenforceability was proposed on two grounds. First, for the clause being a forward contract prohibited under Section 16 of SCRA read with SEBI March 2000 notification, which recognizes only spot delivery transactions to be valid. Secondly these clauses were illegal because they contained an option concerning a future purchase of shares and were thus a derivatives contract not traded on a recognized stock exchange and thus were illegal under Section 18 of SCRA, which deals with derivative trading.

Aggrieved by the arbitrator’s order, Edelweiss challenged it before the Bombay High Court under section 34 of the Arbitration & Conciliation Act, 1996.

The Judgement

The Bombay High Court observed the reasoning of the order by the arbitrator and the contentions made by Percept. The said order confirmed the breach caused by Percept, but found the particular clauses of put option in the SPA to be illegal under two grounds as mentioned earlier. The Court divided the judgement along the sections involved.

The first of the arbitrator’s conclusion was found untenable when referred to the judgement in the case of MCX Stock Exchange Ltd. vs. SEBI [2]which deals with such a purchase option as in the present case. The Court observed that the put option clause contained in the SPA cannot be a derivatives contract prohibited by SCRA, because there was no present obligation at all and the obligation arose by reason of a contingency occurring in the future. The contract only came into being upon the following two conditions being met: (i) failure of the condition attributable to Percept (ii) exercise of the option by Edelweiss upon such failure. Whereas a forward contract is an unconditional obligation, the option in the SPA only comes into being when the aforesaid conditions are met. Thus, the arbitrator’s claim of the clause being a forward contract disregards the law stated by the Court in MCX Stock (supra).

Subsequently, respondent (Percept Group) challenged the relevance of the MCX Stock case to the present one. In the MCX Stock Exchange case, upon the exercise of the option the contract would be fulfilled by means of a spot delivery, that is, by immediate settlement. Whereas Edelweiss’s letter by which it exercised the put option required the shares to be re-purchased with immediate effect or before 12 Jan, 2009. This deferral of repurchase upon exercise of the option was not part of the MCX Stock Exchange case’s option clause and hence is not comparable to the present case.

This too was disregarded by the Court on the ground:

“It is submitted that in as much as this exercise of options demands repurchase on or before a future date, it is not a contract excepted by the circular of the SEBI dated 1 March, 2000.

Just because the original vendor of securities is given an option to complete repurchase of securities by a particular date it cannot be said that the contract for repurchase is on any basis other than spot delivery.

There is nothing to suggest that there is any time lag between payment of price and delivery of shares.”

Now, this brings us to the second leg of the arbitrator’s award regarding the illegality and unenforceability of the SPA option on account of breach of Section 18A of SCRA, which deals in derivative trading. The following is an excerpt from Section 18A:

Contracts in derivative. — Notwithstanding anything contained in any other law for the time being in force, contracts in derivative shall be legal and valid if such contracts are—

(a)Traded on a recognized stock exchange;

(b) Settled on the clearing house of the recognized stock exchange. In accordance with the rules and bye-laws of such stock exchange.

The respondent appeals that as the put option was not of a recognized stock exchange, it stands unenforceable and illegal. In response, the court submitted that the contract does contain a put option in securities which the holder may or may not exercise. But the real question is whether such option or its exercise is illegal? The presence of the option does not make it bad or impermissible.

“What the law prohibits is not entering into a call or put option per se; what it prohibits is trading or dealing in such option treating it as a security. Only when it is traded or dealt with, it attracts the embargo of law as a derivative, that is to say, a security derived from an underlying debt or equity instrument.”

There was further cross objections filed by the respondent but it was ruled out under Section 34 of the Arbitration & Conciliation Act, which deals with the application for setting aside arbitral award. Since the provisions of Civil Procedure Code, 1908 are not applicable to the proceedings under Section 34 and the section itself does not make any provision for filing of cross objections, the appeal was ruled out.

Conclusion

This Bombay High Court ruling in favor of Edelweiss provides an important distinction of options, from forward contracts. It highlighted that although both options and forwards are commonly categorized as derivatives, they share an important difference. On one hand, a forward contract contains a contractual obligation to buy or sell, on the other hand, the option gives the holder the right or choice but not the obligation to do the same. Options have always been integral to finance, routinely appearing in corporate covenants and contracts. Options are widely observed in mezzanine financing, private equity, start-up and venture funding among others. Given the Court’s distinction of forwards from options in their very essence and nature, the author believes this ruling is likely to be useful and a point of reference in future derivative litigations.

[1]https://bombayhighcourt.nic.in/generatenewauth.php?auth=cGF0aD0uL2RhdGEvanVkZ2VtZW50cy8yMDE5LyZmbmFtZT1PU0FSQlAxNDgxMTMucGRmJnNtZmxhZz1OJnJqdWRkYXRlPSZ1cGxvYWRkdD0wMi8wNC8yMDE5JnNwYXNzcGhyYXNlPTA0MDYxOTEwMDAyOQ==

Union Budget 2019-20: Impact on Corporate and Financial sector

/0 Comments/in Bond Market, Capital Markets, Financial Services, Good & Service Tax (GST), Housing finance, Insolvency and Bankruptcy, NBFCs, RBI, Taxation, UPDATES /by Vinod Kothari ConsultantsMunicipal Bonds-Way Forward

/0 Comments/in Bond Market, Capital Markets, Corporate Laws, Financial Services, SEBI, UPDATES /by Vinod Kothari ConsultantsSafe in sandbox: India provides cocoon to fintech start-ups

/0 Comments/in Capital Markets, Financial Services, Fintechs and Payment and Settlement Systems, Publications, RBI, UPDATES /by Vinod Kothari Consultants-Kanakprabha Jethani

kanak@vinodkothari.com, finserv@vinodkothari.com

Published on April 22, 2019 | Updated as on April 22, 2020

Background

April 2019 marks the introduction of a structured proposal[1] on regulatory sandboxes (“Proposal”). ‘Sandboxes’ is a new term and has created a hustle in the market. What are these? What is the hustle all about? The following article gives a brief introduction to this new concept. With the rapidly evolving entities based on financial technology (Fintech) having innovative and complex technical model, the regulators have also been preparing themselves to respond and adapt with changing times. To harness such innovative business concepts, several developed countries and emerging economies have recognised the concept of ‘regulatory sandboxes’. Regulatory sandboxes or RS is a framework which allows an innovative startup involved in financial technologies to undergo live testing in a controlled environment where the regulator may or may not permit certain regulatory relaxations for the purpose of testing. The objective of proposing RS is to allow new and innovative projects to conduct live testing and enable learning by doing approach. The objective behind the framework is to facilitate development of potentially beneficial but risky innovations while ensuring the safety of end users and stability of the marketplace at large. Symbolically, RSs’ are a cocoon in which the startups stay for some time undergoing testing and growing simultaneously, and where it is determined whether they should be launched in the market. In furtherance to the recommendation of an inter-regulatory Working Group (WG) vide its Report on FinTech and Digital Banking1 , the Reserve Bank of India has released the draft ‘Enabling Framework for Regulatory Sandbox’ on April 18, 20192 . The final guidelines shall be released based on the comments of the stakeholders on the aforesaid draft.

Benefits and Limitations

Benefits:

- Regulator can obtain a first-hand view of benefits and risks involved in the project and make future policies accordingly.

- Product can be tested without an expensive launch and any shortcoming thereto can be rectified at initial stages.

- Improvement in pace of innovation, financial inclusion and reach.

- Firms working closely with RS’s garner a greater degree of legitimacy with investors and customers alike.

Limitations:

- Applicant may tend to lose flexibility and time while undergoing testing.

- Even after a successful testing, the applicant will require all the statutory approvals before its launch in the market.

- They require time and skill of the regulator for assessing the complex innovation, which the regulator might not possess.

- It demands additional manpower and resources on part of regulator so as to define RS plans and conduct proper assessment.

Emergence of concept of RS

The concept of RS emerged soon after the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) in 2007-08. It steadily gained prominence and in 2012, Project Catalyst introduced by US Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) finally gave rise to the sandbox concept. In 2015, UK Government Office for Science exhibited the benefits of “close collaboration between regulator, institutions and FinTech companies from clinical environment or real people” through its FinTech Future report. In 2016, UK Financial Conduct Authority launched its regulatory sandbox. Emergence of RS in India In February 2018, RBI launched report of working group on FinTech and digital banking. It recommended Institute for Development and Research in Banking Technology (IDRBT) as the entity whose expertise could run RS in India in cooperation with RBI. After immense deliberations and research, RBI announced its detailed proposal on RS in April 2019. Some of the provisions of the proposal are described hereunder.

Who can apply?

A FinTech firm which fulfills criteria of a startup prescribed by the government can apply for an entry to RS. Few cohorts are to be run whereby there will be a limited number of entities in each cohort testing their products during a stipulated period. The RS must be based on thematic cohorts focusing on financial inclusion, payments and lending, digital KYC etc. Generally , 10-12 companies form part of each cohort which are selected by RBI through a selection process detailed in “Fit and Proper Criteria for Selection of Participants in RS”. Once approval is granted by RBI, the applicant becomes entity responsible for operating in RS. Focus of RBI while selecting the applicants for RS will be on following products/services or technologies:

Innovative Products/Services

- Retail payments

- Money transfer services

- Marketplace lending

- Digital KYC

- Financial advisory services

- Wealth management services

- Digital identification services

- Smart contracts

- Financial inclusion products

- Cyber security products Innovative Technology

- Mobile technology applications (payments, digital identity, etc.)

- Data Analytics

- Application Program Interface (APIs) services

- Applications under block chain technologies

- Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning applications

Who cannot apply?

Following product/services/technology shall not be considered for entry in RS:

- Credit registry

- Credit information

- Crypto currency/Crypto assets services

- Trading/investing/settling in crypto assets

- Initial Coin Offerings, etc.

- Chain marketing services

- Any product/services which have been banned by the regulators/Government of India

For how long does a company stay in the cocoon?

A cohort generally operates for a period of 6 months. However, the period can be extended on application of the entity. Also, RBI may, at its discretion discontinue testing of certain entities which fails to achieve its intended purpose. RS operates in following stages:

| S.No. | Stage | Time period | Purpose |

| 1 | Preliminary screening | 4 weeks | The applicant is made aware of objectives and principles of RS. |

| 2 | Test design | 3 weeks | FinTech Unit finalises the test design of the entity. |

| 3 | Application assessment | 3 weeks | Vetting of test design and modification. |

| 4 | Testing | 12 weeks | Monitoring and generation of evidence to assess the testing. |

| 5 | Evaluation | 4 weeks | Viability of the project is confirmed by RBI |

An alternative to RS

An alternative approach used in developing countries is known as the “test and learn” approach. It is a custom-made solution created by negotiations and dialogue between regulator and innovator for testing the innovation. M-PESA in Kenya emerged after the ‘test-and-learn’ approach was applied in 2005. The basic difference between RS and test-and-learn approach is that a RS is more transparent, standardized and published process. Also, various private, proprietary or industry led sandboxes are being operated in various countries on a commercial or non-commercial basis. They conduct testing and experimentation off the market and without involvement of any regulator. Asean Financial Innovation Network (AFIN) is an example of industry led sandbox.

Globalization in RS

A noteworthy RS in the Global context has been the UK’s Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) which has accepted 89 firms since its launch in 2016. It was one of the early propagators to lead the efforts for GFIN and a global regulatory sandbox. Global Financial Innovation Network (GFIN) is a network of 11 financial regulators mostly of developed countries and related organizations. The objective of GFIN is to establish a network of regulators, to frame joint policy and enable regulator collaboration as well as facilitate cross border testing for projects with an international market in view.

Final framework for RS

RBI introduced final framework[2] for the RS on August 13, 2019 which is almost on the same lines as the Proposal as mentioned above. However the RBI has relaxed the minimum capital requirement to Rs 25 lakhs in place of Rs. 50 lakhs as required under the draft framework with a view to expand the scope of eligible entities.

SEBI’s framework for RS

In May 2019, SEBI also came up with a discussion paper on RS for entities registered with SEBI under section 12 of SEBI Act. The framework was later on finalised in a board meeting of SEBI held in 2020. In line with the finalised framework, various SEBI regulations have also been amended to include a new chapter, allowing case-to-case based exemptions to entities operating in RS.

The SEBI framework is slightly different from the one prescribed by the RBI. SEBI has kept an open window for accepting applications under the RS framework, while the RBI will accept applications under theme-based cohorts. Further, RBI allows entities registered with it as well as other start-ups to apply for entry into RS. However, for the time being, SEBI has allowed only the entities registered under section 12 of SEBI Act to apply. Intermediaries that are registered under section 12 of SEBI Act are as follows:

- stock broker

- sub-broker

- share transfer agent

- banker to an issue

- trustee of trust deed

- registrar to an issue

- merchant banker

- underwriter

- portfolio manager

- investment adviser

-

depository

-

depository participant

-

custodian of securities

- credit rating agencies

- any other intermediary associated with the securities market

In the due course of time, SEBI may allow applications by other entities not registered with it.

Conclusion

Regulatory sandboxes were introduced with a motive to enhance the outreach and quality of FinTech services in the market and promote evolution of FinTech sector. Despite certain limitations, which can be overcome by using transparent procedures, developing well-defined principles and prescribing clear entry and exit criteria, the proposal is a promising one. It strives to strike a balance between financial stability and consumer protection along with beneficial innovation. It Is also likely to develop a market which supports a regulated environment for learning by doing in the scenario of emerging technologies.

[1] https://www.rbi.org.in/scripts/BS_PressReleaseDisplay.aspx?prid=46843

[2] https://www.rbi.org.in/scripts/PublicationReportDetails.aspx?ID=938

State of Bond Market in India

/0 Comments/in Bond Market, Capital Markets, Companies Act 2013, Financial Services, RBI, SEBI /by Vinod Kothari ConsultantsShould OCI be included as a part of Tier I capital for financial institutions?

/2 Comments/in Bond Market, Financial Services, NBFCs /by Vinod Kothari ConsultantsIndia has been adopted International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) in the form of Indian Accounting Standards (Ind AS) in a phased manner since 2016. Different implementation schedules have been issued by different regulatory authorities for different classes of companies and they are:

- Ministry of Corporate Affairs –

- For non-banking non-financial companies – Implementation schedule started from 1st April, 2016

- For non-banking financial companies – Implementation schedule started from 1st April, 2018

- Reserve Bank of India –

- For banking companies – The original scheduled start date was 1st April, 2018, subsequently, it was shifted to 1st April, 2019. However, a recent notification from the RBI has shifted the implementation schedule indefinitely.[1]

- Insurance Regulatory Development Authority of India –

- For insurance companies – The implementation schedule starts from 1st April, 2020.

Consequent upon implementation of IFRS, it is logical that the regulatory framework for financial institutions will also require modifications to bring it in line with the provisions requirements under the new standards.

Though the Ind AS already been implemented in the NBFC sector, no modifications in the existing regulations have been made. Consequently, this has led to the creation of several ambiguities; and one such is regarding treatment of the Other Comprehensive Income (OCI), as per Ind AS 109, for the purpose of computing Tier 1 capital.

This write up will solely focus on the issue relating to treatment of OCI for the purpose of Tier 1 capital.

Other Comprehensive Income (OCI)

Before delving further into specifics, let us have a quick recap of the concept of the OCI. The format of income reporting under Ind AS has undergone a significant change. Under Ind AS, the statement of profit or loss gives us Total Comprehensive Income which consists of a) profit or loss for the period and b) OCI. While the first component represents the profit or loss earned by the reporting entity during the financial year, OCI represents unrealized gains or losses from financial assets of the reporting entity.

The intention of showing OCI in the books of the accounts, is that it protects the gains/losses of companies from oscillation. As the fair values of assets and liabilities fluctuate with the market, parking the unrealized gains in the OCI and not in the P/L account provides stability. In addition to investment and pension plan gains and losses, OCI also captures that the hedging transactions undertaken by the company. By segregating OCI transactions from operating income, a financial statement reader can compare income between years and have more clarity about the sources of income.

While profit or loss earned during the year forms part of the surplus or other reserves in the balance sheet, OCI is shown separately under the Equity segment of the balance sheet.

Capital Risk Adequacy Ratio

Moving on to the meaning of capital risk adequacy ratio (CRAR), it is a measurement of a bank’s available capital expressed as a percentage of a bank’s risk-weighted credit exposures. The CRAR is used to protect creditors and promote the stability and efficiency of financial institutions. This in turn results in providing protection against insolvency. Two types of capital are measured: Tier-I capital, which can absorb losses without a bank being required to cease trading, and Tier-II capital, which can absorb losses in the event of a winding-up and so provides a lesser degree of protection to depositors.

The concept of CRAR comes from the Basel framework laid down by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS), a division of Bank of International Settlement. The latest framework being followed worldwide is Basel III framework.

RBI has also adopted the Basel framework, however, with modifications to suit the economic environment in the country. The CRAR requirements have been made applicable to banks as well as NBFCs, however, the requirements vary. While banks are required to maintain 9% CRAR, NBFCs are required to maintain 15% CRAR.

To understand whether OCI should form part of CRAR, it is important to understand the components of CRAR.

Components of Tier I and II Capital as per RBI Master Directions[2] for NBFCs

For the purpose of this write-up, requirements have been examined only from the point of view of NBFCs, as Ind AS is yet to be implemented for banking companies.

CRAR comprises of two parts – Tier I capital and Tier II capital. Each of the two have been defined in the Master Directions issued by the RBI, in the following manner:

(xxxii) “Tier I Capital” means owned fund as reduced by investment in shares of other non-banking financial companies and in shares, debentures, bonds, outstanding loans and advances including hire purchase and lease finance made to and deposits with subsidiaries and companies in the same group exceeding, in the aggregate, ten percent of the owned fund; and perpetual debt instruments issued by a non-deposit taking non-banking financial company in each year to the extent it does not exceed 15% of the aggregate Tier I Capital of such companies as on March 31 of the previous accounting year;

The term “owned funds” have been defined as:

“owned fund” means paid up equity capital, preference shares which are 9 compulsorily convertible into equity, free reserves, balance in share premium account and capital reserves representing surplus arising out of sale proceeds of asset, excluding reserves created by revaluation of asset, as reduced by accumulated loss balance, book value of intangible assets and deferred revenue expenditure, if any;

Tier II capital has been defined as:

(xxxiii) “Tier II capital” includes the following:

- preference shares other than those which are compulsorily convertible into equity;

- revaluation reserves at discounted rate of fifty five percent;

- General provisions (including that for Standard Assets) and loss reserves to the extent these are not attributable to actual diminution in value or identifiable potential loss in any specific asset and are available to meet unexpected losses, to the extent of one and one fourth percent of risk weighted assets;

- hybrid debt capital instruments;

- subordinated debt; and

- perpetual debt instruments issued by a non-deposit taking non-banking financial company which is in excess of what qualifies for Tier I Capital, to the extent the aggregate does not exceed Tier I capital.

The above definitions of Tier I and II capital do not talk about OCI. However, the Directions were prepared before the implementation of Ind AS 109 and no clarity on the subject has come from RBI post implementation of Ind AS 109.

Therefore, for determining whether OCI should be made a part of Tier I or Tier II capital, we can draw reference from Basel III framework.

Components of Tier I capital as per Basel III framework [3]

As per Para 52 of the framework, the Tier I capital consists of:

Common Equity Tier 1 capital consists of the sum of the following elements:

- Common shares issued by the bank that meet the criteria for classification as common shares for regulatory purposes (or the equivalent for non-joint stock companies);

- Stock surplus (share premium) resulting from the issue of instruments included Common Equity Tier 1;

- Retained earnings;

- Accumulated other comprehensive income and other disclosed reserves;

- Common shares issued by consolidated subsidiaries of the bank and held by third parties (ie minority interest) that meet the criteria for inclusion in Common Equity Tier 1 capital. See section 4 for the relevant criteria; and

- Regulatory adjustments applied in the calculation of Common Equity Tier 1

Retained earnings and other comprehensive income include interim profit or loss. National authorities may consider appropriate audit, verification or review procedures. Dividends are removed from Common Equity Tier 1 in accordance with applicable accounting standards. The treatment of minority interest and the regulatory adjustments applied in the calculation of Common Equity Tier 1 are addressed in separate sections.

The Basel III norms clearly states that accumulated other comprehensive income forms a part of the Tier I capital.

It is very interesting to note that RBI had also adopted Basel III framework on July 1, 2015, however, the framework adopted and introduced is silent on the treatment of the OCI, unlike the original Basel III framework. The reason for the omission of the concept of OCI is that the framework was adopted in India way before Ind AS implementation and under the erstwhile IGAAP, there was no concept of OCI or booking of unrealized gains or losses in the books of accounts.

It is well understood that due to the very recent implementation of IndAS 109, the guidelines have not been revised in line with the IndAS. However, going by the spirit of Basel III regulation, this leaves us very little doubt what the treatment of OCI for the purpose of CRAR computation should be. Therefore, one can safely conclude that the OCI should form part of Tier I capital, unless, anything contrary is issued by the RBI subsequently.

[1] https://www.rbi.org.in/Scripts/NotificationUser.aspx?Id=11506&Mode=0

[2] https://rbidocs.rbi.org.in/rdocs/notification/PDFs/45MD01092016B52D6E12D49F411DB63F67F2344A4E09.PDF0