A guide to concepts, taxation, and accounting aspects of sale and leaseback transactions.

Contents

Sale and Leaseback transaction. 2

Advantages to the Lessee. 2

Unlocking value, the hidden value of asset 2

Tax Benefits. 2

Legal issues in SLB: 3

Taxation of SLB transactions. 3

Direct Tax Aspect 3

Goods & Service Tax. 5

The Sale. 5

The Lease. 5

Place of supply. 6

Disposal of Capital Asset 6

Example of GST Calculations on Sale and Leasebacks. 6

Sale of Asset 7

Leasing of asset 7

Accounting of Sale and leasebacks. 7

Criteria for Sale. 8

Transfer of asset does not qualify as sale. 10

Transfer of asset qualifies as sale. 10

Sale at Fair Value. 10

Sale at a discount or premium.. 10

Example of Sale and Leaseback Accounting under Ind AS 109. 11

Calculations. 11

Rental Schedule. 11

Accounting Entries at Inception. 12

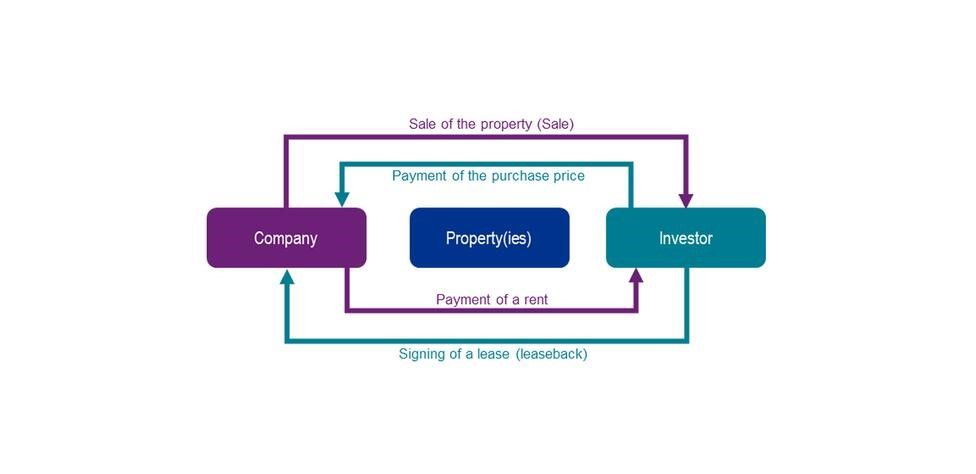

Sale and Leaseback transaction

A Sale and Leaseback (SLB) is a special case of application of leasing technique. Lease is a preferred mode of using the asset without having to own it. In case of leases, the lessee does not own the asset but acquires the right to use the asset for a specified period of time and pays for the usage.

SLB is a simple financial transaction which allows selling an asset and then taking it back on lease. The transaction thus allows a seller to be able to use the asset and not own it, at the same time releasing the capital blocked by the asset.

SLB allows the lessee to detach itself with legal ownership yet continuing to use the asset as well. In effect there is no movement of asset however on paper there is a change in the title of the asset.

Sale and Leaseback transactions are globally common in the Real estate investment trusts (REITs) and Aviation industry.

Advantages to the Lessee

Unlocking value, the hidden value of asset

As is evident from the mechanics of SLB above, SLB results in taking the asset off the books of the lessee and results in upfront cash which could be used for paying off existing liabilities. Hence this does not impact the existing lines of credit the lessee may be availing.

SLB can help entities raise finance for an amount equal to fair market value of the asset which may be significantly higher than its book value. Though there might be taxation challenges attached to it in Indian context. Nevertheless, SLB may bring about a financial advantage as well wherein a high-cost debt can be substituted with a low-cost lease liability.

Most of the assets considered for SLB have been used by the lessee for a substantial period of time and the value of the physical assets may be insignificant. Hence SLB is sometimes referred to as junk financing.

Tax Benefits

SLB may sometimes lead to tax benefits as well (we shall see this in detail in the sections below). This has been one of the major drivers of SLB transactions in India and has its own downsides as well. One of the major pitfalls to SLB is the danger of excess leveraging; the lessee may tend to overvalue the asset. Considering that SLB is a mode of asset-backed lending but the asset has may not have much value and the lessee may exercise discretion on the application of funds poses threat of misuse of the product.

Legal issues in SLB:

The legal validity of SLB was discussed by the U.S Supreme Court in the landmark ruling of Frank Lyon and Company[1]. In Frank Lyon’s case the bank took the building on SLB. Under the lease terms the bank was liable to pay rentals periodically and had the option to purchase the building at various times at a consideration based on its outstanding balance. The bank took possession of the building in the year it was completed and the lessor claimed deductions on depreciation, interest on construction loan, expenses related to sale and lease back and accrued the rent from the bank.

The Commissioner of Internal Revenue denied the claims of the petitioner on the grounds that the petitioner was not the owner of the building and the sale and leaseback was a mere financing transaction. The Hon’ble Court held that –

Where, as here, there is a genuine multiple-party transaction with economic substance that is compelled or encouraged by business or regulatory realities, that is imbued with tax-independent considerations, and that is not shaped solely by tax-avoidance features to which meaningless labels are attached, the Government should honor the allocation of rights and duties effectuated by the parties; so long as the lessor retains significant and genuine attributes of the traditional lessor status, the form of the transaction adopted by the parties governs for tax purposes.

The fundamental principle is that the Court should be concerned with the real substance of the transaction rather than the form of the same. If there are reasons to believe that the form of the transaction and its real substance are not aligned, the Court must not be simply concerned by the form of the transaction nor by the nomenclature that the parties have given to it.

In India too, the legality of SLB transactions have been questioned in several cases; sometimes the transactions have come out clean while in some cases, SLBs were considered an accounting gimmick.

The legality of SLB transactions and analysis of various judicial pronouncements on the same, have been discussed in detail in our write up “Understanding Sale and leaseback”

Taxation of SLB transactions

Tax aspects specifically direct tax acts as a major motivation behind such transactions, SLB provides a creative playground for finance professionals to structure transactions in a manner that can lead to substantial benefit to the entity, and taxation acts as a major tool at their disposal.

Direct Tax Aspect

Though tax benefits have been a motivator for SLB transaction, the same has also been the reason for near wipe-out of SLB from Indian markets.

During the 1996-98 period one of the most infamous cases was the sale and leaseback of electric meters by state electricity boards (SEBs). For SEBs it made perfect sense as it amounted to cheap borrowing by the cash starved SEBs who had practically no other source of borrowing.

For leasing companies and others looking for a tax break, it was a perfect deal as there was 100% write off in case of assets costing Rs 5000 or less. Thus, an electric meter will qualify for 100% deduction. Several SEBs had undertaken such transactions in those days. Obvious enough the sole motive was tax deduction no one would care about the value, quality, existence etc of the meters. In some cases, the asset was bought on 30th March to be used only for a day, assets revalued heavily at the time of sale to leasing companies etc. Lease of non-existing assets such as electric meters, computers, glass bottles, tools, etc, lure of depreciation allowances caused the tax authorities to come down hard on sale and leaseback transactions calling them tax evading transactions. The whole fiasco of such sham transactions resulted in leasing going off the market completely. The burns of the past continue to linger even after a decade and half since SLB transactions were completely written off.

The most significant consideration in lease transactions is the depreciation claim. For tax purposes, depreciation is calculated on the block of the assets and not on the written down value of each asset separately.

Section 2(11) of the Income Tax Act, 1961 (IT Act) defines block of assets to mean

“”block of assets” means a group of assets falling within a class of assets comprising—

(a) tangible assets, being buildings, machinery, plant or furniture;

(b) intangible assets, being know-how, patents, copyrights, trade-marks, licences, franchises or any other business or commercial rights of similar nature, in respect of which the same percentage of depreciation is prescribed.”

The sale proceeds of the assets sold are deducted from the written down value of the block. In case of SLB transaction, assets are sold at higher than written down value, and the gain made on such a sale results in reduction in depreciable value of the block of assets. The reduction in depreciation will be allowed over a number of years. Similar would be the case in case the asset was sold at less than written down value, sale consideration would be reduced from the block of the assets.

Once the asset is sold and taken off the books of the lessee, the lessee is able to account for an immediate accounting profit without having to pay tax on it instantly. As under the block concept of depreciation, when the lessee sells the capital assets, the sale proceeds including the profits on sale are allowed to be deducted from the block of assets and hence there is no immediate tax on the accounting profits.

Also, typically the asset is recorded on historical costs which may be lower than the intrinsic value of the asset. SLB sometimes allows the entities to unlock the appreciation in value. However, it is not always necessary that the asset would have appreciated value. In some cases, the asset may have become junk completely.

To avoid the same revenue has introduced following provisions in the IT act, in order to restrict undue benefits being passed by use of sham SLB transactions:

Section 43 (1) provides for treatment of sale and lease back transactions for tax purposes, the relevant extracts are reproduced below –

“Explanation 3.—Where, before the date of acquisition by the assessee, the assets were at any time used by any other person for the purposes of his business or profession and the Assessing Officer is satisfied that the main purpose of the transfer of such assets, directly or indirectly to the assessee, was the reduction of a liability to income-tax (by claiming depreciation with reference to an enhanced cost), the actual cost to the assessee shall be such an amount as the Assessing Officer may, with the previous approval of the Joint Commissioner, determine having regard to all the circumstances of the case.”

“Explanation 4A.—Where before the date of acquisition by the assessee (hereinafter referred to as the first mentioned person), the assets were at any time used by any other person (hereinafter referred to as the second mentioned person) for the purposes of his business or profession and depreciation allowance has been claimed in respect of such assets in the case of the second mentioned person and such person acquires on lease, hire or otherwise assets from the first mentioned person, then, notwithstanding anything contained in Explanation 3, the actual cost of the transferred assets, in the case of first mentioned person, shall be the same as the written down value of the said assets at the time of transfer thereof by the second mentioned person.

Explanation 3 and 4A of Section 43 (1) restricts the consideration at which the lessor purchases the assets to written down value of the asset as appearing in the books of the lessee before it was sold and taken back on lease. The explanation explicitly states that the sale value for such sale and lease back transactions will be ignored and depreciation will be allowed on the first seller’s depreciated value. Take, for instance, A purchased machinery for Rs. 10 crores from B, though the WDV in the books of B is Rs. 2 crores. A can claim depreciation on Rs. 2 crores and not on Rs. 10 crores.

The said provisions removes any motivation for the lessor to carryout transactions at inflated values. Hence preventing junk financing to enter into SLB transactions.

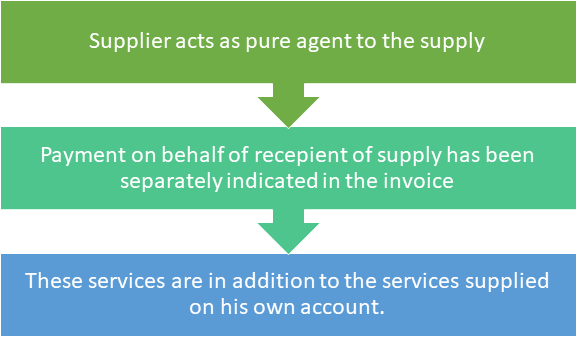

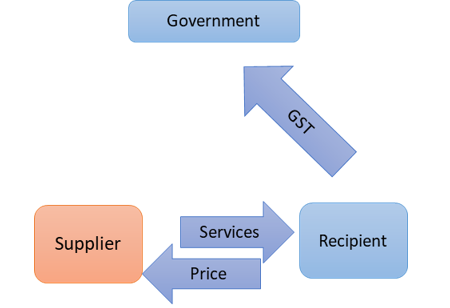

Goods & Service Tax

Pre-GST indirect taxation regime acted as a major road block in the development of leasing industry as a whole, the legal differentiation as well as non-availability of credit among central and state taxes made leasing transactions costly.

Introduction of GST is playing a key role in development of leasing industry, from a stage where it had nearly become extinct. We have further discussed GST implications on leasing.

The Sale

The first leg of the transaction would involve sale of Assets by lessee to lessor.

In terms of section 7(1)(a) “all forms of supply of goods or services or both such as sale, transfer, barter, exchange, licence, rental, lease or disposal made or agreed to be made for a consideration by a person in the course or furtherance of business;”

The taxability under GST arises on the event of supply accordingly the sale of capital assets for a consideration would fall under the ambit of supply and accordingly GST shall be levied.

The Lease

The second part of transaction would lease back that is when the asset is leased back from buyer -lessor to seller lessee. The leaseback would be subject to GST like any other lease transaction.

The term lease has not been defined anywhere in GST Act or Rules. To classify a lease transaction as either supply of goods or supply of service, we have to refer Schedule II of the CGST Act, 2017 where in clear guidelines for classification of a transaction as either “supply of goods” or “supply of services” has been enumerated, based on certain parameters: –

- Any transfer of the title in goods is a supply of goods;

- Any transfer of right in goods or of undivided share in goods without the transfer of title thereof, is a supply of services;

- Any transfer of title in goods under an agreement which stipulates that property in goods shall pass at a future date upon payment of full consideration as agreed, is a supply of goods.

- Any lease, tenancy, easement, licence to occupy land is a supply of services;

- Any lease or letting out of the building including a commercial, industrial or residential complex for business or commerce, either wholly or partly, is a supply of services.

Place of supply

Undoubtedly, the SLBs do not involve movement of goods, the seller lessee continuous to be in possession of leased asset even after the sale. Hence, In the case of such sale, there is no physical movement of the asset from the premises of the lessee to the premises of the lessor. The ownership gets transferred in the premise of the lessee.

In terms of Section 10(1)(c) of the IGST Act, the place of supply of goods where the supply does not involve movement of the said goods whether by the supplier or the recipient shall be the location of such goods at the time of delivery to the recipient. Accordingly, the place of supply in this case will be same as the location of the supplier. Accordingly, the sale of the asset will be considered as an intra-state supply as per Section 8 of the IGST Act and will be subjected to CGST + SGST.

Disposal of Capital Asset

Applications of GST on disposal of capital assets is one of the major deterring factors of in SLBs. Section 18(6) of the CGST Act,2017 state that:

“In case of supply of capital goods or plant and machinery, on which input tax credit has been taken, the registered person shall pay an amount equal to the input tax credit taken on the said capital goods or plant and machinery reduced by such percentage points as may be prescribed or the tax on the transaction value of such capital goods or plant and machinery determined under section 15, whichever is higher:”

Entry no. (6) Of Rule 44 of CGST Rules, 2017: Manner of Reversal of ITC under Special Circumstances which reads as under: –

“The amount of input tax credit for the purposes of sub-section (6) of section 18 relating to capital goods shall be determined in the same manner as specified in clause (b) of sub-rule (1) and the amount shall be determined separately for input tax credit of central tax, State tax, Union territory tax and integrated tax:”

“……………..Clause (b) of sub rule 1 of same rules states that :

(b) for capital goods held in stock, the input tax credit involved in the remaining useful life in months shall be computed on pro-rata basis, taking the useful life as five years………….”

Generally, the lessor procures the capital Assets at WDV due to Income tax Act implication. In that case WDV as per Income tax act would be the transaction value.

Example of GST Calculations on Sale and Leasebacks

Let’s consider a numerical example: an Entity A enters into SLB arrangement with an Entity B. A sells its machinery to B for Rs. 5,00,000/- as on 31st May 2021. The entity had purchased the asset for Rs. 6,00,000/- as on 31st March 2019.

B then leases back the asset to A for a yearly rental of Rs, 1,00,000/- for 3 years term with a purchase option at the end of 4th year at Rs. 2,50,000. (Assumed to be exercised)

(GST @ 18%)

Sale of Asset

Disposal of assets

On disposal asset, GST will be charged on the selling price of the asset. However, the amount to be deposited to the government with respect to this sale transaction shall be higher of the following:

- GST on the sale consideration;

- ITC reversed on transfer of capital asset or plant and machinery based on the prescribed formula

Portion of ITC availed on the asset, attributable to the period during which the transferor used the asset:

6,00,000 * 18% * (5% * 8) = 43200

Remaining ITC = (6,00,000 * 18%) – 43200 = 64800

GST on the selling price = 500000 * 18% = 90000

Therefore, GST to be paid to the government is 90000, that is higher of the two amounts discussed above.

Leasing of asset

As mentioned above GST shall be chargeable to lease rental, at the rate similar to that charged on acquisition of leased asset. Accordingly, Entity B shall charge GST on rentals for an amount of Rs. 18,000/- (Rs. 1,00,000/- * 18%).

Further GST shall also be charged on sale of asset at the end of lease tenure for an amount of Rs. 45,000/-(2,50,000*18%).

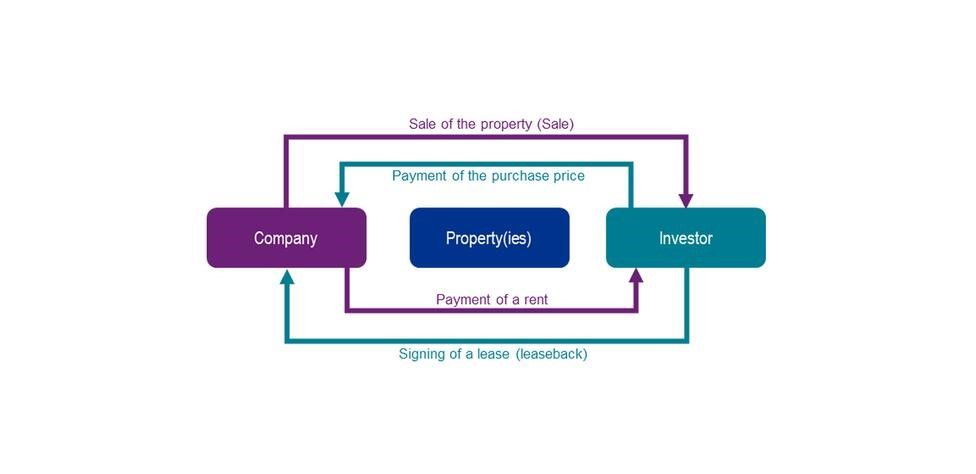

Accounting of Sale and leasebacks

IAS 17 covered the accounting for a sale and leaseback transaction in considerable detail but only from the perspective of the seller-lessee.

As Ind AS 116/IFRS 16 has withdrawn the concepts of operating leases and finance leases from lessee accounting, the accounting requirement that the seller-lessee must apply to a sale and leaseback is more straight forward.

The graphic below shows how SLB transactions should be accounted for:

Criteria for Sale

IFRS 16/Ind AS 116 state that

“ An entity shall apply the requirements for determining when a performance obligation is satisfied in Ind AS 115 to determine whether the transfer of an asset is accounted for as a sale of that asset.”

Accordingly, when a seller-lessee has undertaken a sale and lease back transaction with a buyer-lessor, both the seller-lessee and the buyer-lessor must first determine whether the transfer qualifies as a sale. This determination is based on the requirements for satisfying a performance obligation in IFRS 15/Ind AS 115 – “Revenue from Contracts with Customers”.

The accounting treatment will vary depending on whether or not the transfer qualifies as a sale.

The para 38 of Ind AS 115/IFRS 15- Performance obligations satisfied at a point in time, provides ample guidance on determining whether the performance obligation is satisfied.

The para states that:

“If a performance obligation is not satisfied over time in accordance with paragraphs 35– 37, an entity satisfies the performance obligation at a point in time. To determine the point in time at which a customer obtains control of a promised asset and the entity satisfies a performance obligation, the entity shall consider the requirements for control in paragraphs 31–34. In addition, an entity shall consider indicators of the transfer of control, which include, but are not limited to, the following:

(a) The entity has a present right to payment for the asset—if a customer is presently obliged to pay for an asset, then that may indicate that the customer has obtained the ability to direct the use of, and obtain substantially all of the remaining benefits from, the asset in exchange.

(b) The customer has legal title to the asset—legal title may indicate which party to a contract has the ability to direct the use of, and obtain substantially all of the remaining benefits from, an asset or to restrict the access of other entities to those benefits. Therefore, the transfer of legal title of an asset may indicate that the customer has obtained control of the asset. If an entity retains legal title solely as protection against the customer’s failure to pay, those rights of the entity would not preclude the customer from obtaining control of an asset.

(c) The entity has transferred physical possession of the asset—the customer’s physical possession of an asset may indicate that the customer has the ability to direct the use of, and obtain substantially all of the remaining benefits from, the asset or to restrict the access of other entities to those benefits. However, physical possession may not coincide with control of an asset. For example, in some repurchase agreements and in some consignment arrangements, a customer or consignee may have physical possession of an asset that the entity controls. Conversely, in some bill-and-hold arrangements, the entity may have physical possession of an asset that the customer controls. Paragraphs B64–B76, B77–B78 and B79–B82 provide guidance on accounting for repurchase agreements, consignment arrangements and bill-and-hold arrangements, respectively.

(d) The customer has the significant risks and rewards of ownership of the asset—the transfer of the significant risks and rewards of ownership of an asset to the customer may indicate that the customer has obtained the ability to direct the use of, and obtain substantially all of the remaining benefits from, the asset. However, when evaluating the risks and rewards of ownership of a promised asset, an entity shall exclude any risks that give rise to a separate performance obligation in addition to the performance obligation to transfer the asset. For example, an entity may have transferred control of an asset to a customer but not yet satisfied an additional performance obligation to provide maintenance services related to the transferred asset.

(e) The customer has accepted the asset—the customer’s acceptance of an asset may indicate that it has obtained the ability to direct the use of, and obtain substantially all of the remaining benefits from, the asset. To evaluate the effect of a contractual customer acceptance clause on when control of an asset is transferred, an entity shall consider the guidance in paragraphs B83–B86.”

It shall be noted that no single criteria can be taken as a determining factor for concluding that sale has taken place. Each criterion should be individually assessed every case. Needless to say, substance of the transaction should be adjudge based on principles set.

The criteria set out in the para 38 specified above can be summarised as follows:

- There is a present right to payment has been established.

- The legal tittle of the asset is transferred. It shall be noted that this shall not conclusively determine sale, rather a to be considered in consonance with another criterion.

- Physical possession of the asset has been transferred. Now this is a matter of discussion, as under SLB, the possession never leaves the seller. However, in our view even in case of symbolic transfer of possession the criterion can be said to be satisfied subject to the condition that buyer-lessor has an ability to direct the use of asset. Hence, an entity should ensure that the buyer-lessor is not bound by sale agreement or otherwise to leaseback the asset.

- Significant risk and reward attached to ownership are transferred to the buyer

- The buyer has accepted the asset

Transfer of asset does not qualify as sale

If the transfer does not qualify as a sale the parties account for it as a financing transaction. This means that:

- The seller-lessee continues to recognise the asset on its balance sheet as there is no sale. The seller-lessee accounts for proceeds from the sale and leaseback as a financial liability in accordance with Ind AS 109/IFRS 9. This arrangement is similar to a loan secured over the underlying asset – in other words a financing transaction

- The buyer-lessor has not purchased the underlying asset and therefore does not recognise the transferred asset on its balance sheet. Instead, the buyer-lessor accounts for the amounts paid to the seller-lessee as a financial asset in accordance with Ind AS 109/IFRS 9. From the perspective of the buyer-lessor also, this arrangement is a financing transaction.

Transfer of asset qualifies as sale

Where the transfer qualifies as sale, there can be further two situations:

- Sale at Fair value

- Sale at discount or premium.

Sale at Fair Value

If the transfer qualifies as a sale and is on fair value basis the seller-lessee effectively splits the previous carrying amount of the underlying asset into:

- a right-of-use asset arising from the leaseback, and

- the rights in the underlying asset retained by the buyer-lessor at the end of the leaseback.

The seller-lessee recognises a portion of the total gain or loss on the sale. The amount recognised is calculated by splitting the total gain or loss into:

- an unrecognised amount relating to the rights retained by the seller-lessee, and

- a recognised amount relating to the buyer-lessor’s rights in the underlying asset at the end of the leaseback.

The leaseback itself is then accounted for under the lessee accounting model.

The buyer-lessor accounts for the purchase in accordance with the applicable standards (eg IAS 16 ‘Property, Plant and Equipment’ if the asset is property, plant or equipment or IAS 40 ‘Investment Property’ if the property is investment property). The lease is then accounted for as either a finance lease or an operating lease using IFRS 16’s lessor accounting requirements.

Sale at a discount or premium

The accounting methodology shall remain the same, However, Adjustments would be required to provide for the discounted or premium price.

These adjustments would be as follows:

- a prepayment would be recorded in order to provide for adjustment in regard to sale at a discount

- Any amount paid in excess of fair value would be recorded as an additional financing facility and accounted for under Ind AS 109.

Example of Sale and Leaseback Accounting under Ind AS 109

A sample spreadsheet calculations for the below example can be accessed here

Calculations

| Particular |

Amount |

Remarks |

| Sale considerations |

₹ 10,00,000.00 |

|

| Carrying Amount |

₹ 5,00,000.00 |

|

| Term |

15 |

year |

| Rentals/year |

₹ 80,000.00 |

year |

| Fair Value of Building |

₹ 9,00,000.00 |

|

| Incremental borrowing rate |

10% |

|

| PV of rentals |

₹ 6,08,486.36 |

|

| Additional Financing |

₹ 1,00,000.00 |

Sale Consideration

– Fair Value |

| Payments towards Lease Rentals |

₹ 5,08,486.36 |

PV of Rentals

– Additional Financing |

Ratio of PV of rentals and

Payment towards lease Rentals |

16% |

|

| Yearly payments towards Add. Financing |

₹ 13,147.38 |

Rental X Ratio |

| Yearly payments towards Lease Rental |

₹ 66,852.62 |

Rental – Payment toward Add. Fin. |

| ROU of Asset |

₹ 2,82,492.42 |

Carrying Amount X

[Payments towards Lease Rentals/Fair Value of Building] |

| Total Gain on sale |

₹ 4,00,000.00 |

Fair Value – Carrying Amount |

| Gain recognised Upfront |

₹ 1,74,006.06 |

Total Gain X [(Fair Value of Building-Payments towards Lease Rentals)

/Fair Value of Building] |

Rental Schedule

|

NPV |

NPV |

|

₹ 5,08,486.36 |

₹ 1,00,000.00 |

| Year |

Lease Rentals |

Additional Financing |

| 0 |

|

|

| 1 |

₹ 66,852.62 |

₹ 13,147.38 |

| 2 |

₹ 66,852.62 |

₹ 13,147.38 |

| 3 |

₹ 66,852.62 |

₹ 13,147.38 |

| 4 |

₹ 66,852.62 |

₹ 13,147.38 |

| 5 |

₹ 66,852.62 |

₹ 13,147.38 |

| 6 |

₹ 66,852.62 |

₹ 13,147.38 |

| 7 |

₹ 66,852.62 |

₹ 13,147.38 |

| 8 |

₹ 66,852.62 |

₹ 13,147.38 |

| 9 |

₹ 66,852.62 |

₹ 13,147.38 |

| 10 |

₹ 66,852.62 |

₹ 13,147.38 |

| 11 |

₹ 66,852.62 |

₹ 13,147.38 |

| 12 |

₹ 66,852.62 |

₹ 13,147.38 |

| 13 |

₹ 66,852.62 |

₹ 13,147.38 |

| 14 |

₹ 66,852.62 |

₹ 13,147.38 |

| 15 |

₹ 66,852.62 |

₹ 13,147.38 |

Accounting Entries at Inception

| Buyer-Lessor |

| Building |

₹ 9,00,000.00 |

|

| Financial Asset |

₹ 1,00,000.00 |

|

| Bank |

|

₹ 10,00,000.00 |

| *Lease accounted as per Finance or operating lease accounting |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Seller-Lessee |

| Bank |

₹ 10,00,000.00 |

|

| ROU |

₹ 2,82,492.42 |

|

| Building |

|

₹ 5,00,000.00 |

| Financial Liability |

|

₹ 6,08,486.36 |

| Gains on Asset Transfer |

|

₹ 1,74,006.06 |

[1] 435 U.S. 561 (1978)