Is half-truth a lie: Hidden Costs in zero-interest loans

-Chirag Agarwal & Archisman Bhattacharjee I finserv@vinodkothari.com

In the realm of personal finance, the attraction of borrowing money without incurring interest charges is an enticing prospect. Zero percent interest rate loans, often advertised as promotional offers by retail financing companies, credit card companies, retailers, and financial institutions, have garnered significant attention in recent years. But what exactly are these loans? Are they really zero-interest loans? No one would believe that the lender is getting zero income on the loans. And if the lender is indeed getting some income, even if not from the borrower, that income is not completely disconnected with the loan. Therefore, are there fair disclosure requirements that may require the lender to disclose his yield on the so-called zero interest loans?

Zero percent financing refers to a loan where no interest is applied, either throughout its duration or for a set period.

One form of zero percent interest rate loans is known as merchant subvention. In this model, the seller or manufacturer of the product assumes responsibility for paying the interest to the lender. This arrangement allows the merchant to effectively market and sell the product, attracting more customers to the merchant’s business. Meanwhile, the customer gets the perceived “feel good” benefit of obtaining the product at a zero percent interest rate. If happiness is all about feeling good and not necessarily being good, it is a mutually beneficial situation for the buyer, seller and the lender.

Another form of zero percent loan may be where lenders load additional charges in some form other than interest, and pretend to provide an interest-free loan. These could comprise of of a one-time high processing fees, or similar other charges, which disguise the interest component . This practice, we understand, is deceptive and is against the concept of fair lending. Hence, if the lender is charging interest in form of the so-called “other charges”, and claims to be providing interest-free loan, that is a case of lie. However, in this article, we are not dealing with a lie – we are dealing with a half-truth. .

And what is that half truth? , If the lender is making his target yield by way of third party cashflows, such as merchant subvention, product discount, etc., is it fair for the lender to demonstrate that he is lending free of interest? .

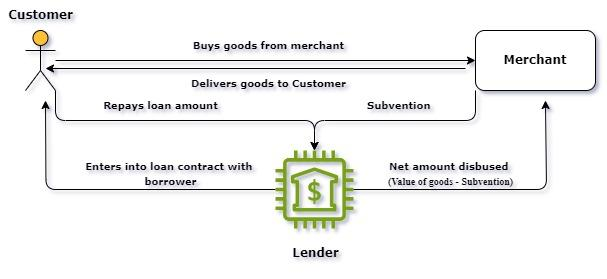

Understanding the mechanism of merchant subvention

It is a well-established practice among dealers or manufacturers to offer subventions or discounts on products to customers availing loans from financial institutions. In such instances, banks/NBFCs, leverage their volumes and vendor relationships to secure favourable terms. Here, it becomes imperative that these benefits are passed on to customers without altering the applicable rate of interest (RoI) of the product. Furthermore, the actual discount is not provided by the bank/NBFC, but by the merchant as a part of the merchant’s customer acquisition strategy. As a regulated entity, the lender is expected to ensure full and transparent disclosure of these benefits to customers

Hence, the lender showing the loan as 0% is essentially passing the discount or benefits provided by the merchant to the lender. It cannot be contended that the lender would have bought the product or service but for the purpose of the loan. In fact, the lender is not the actual purchaser; the lender is simply aiding or pushing the sales of the merchant by offering credit. It is the credit facility that triggers the purchase; it is the purchase that triggers the discount. Hence, there is a clear nexus between the grant of the merchant’s benefits to the lender.

Quite often, the issue is – will the customer be able to get the same discount, subvention or benefits if the customer was to make a direct purchase from the vendor? The answer will mostly be negative. The lender has a relationship with the vendor, whereby the lender gives volumes as well as regular business. But no lender will obviously do a loan without a threshold rate of return. There is absolutely nothing wrong in saying that the interest charged to the customer is zero, but at the same time, to not make basic disclosure about the extent of discount or benefits that the lender gets from the merchant will be a case of half truth.

The following is a diagrammatic illustration of how the concept of merchant subvention works

The concept of annualised percentage rate (APR) has also been introduced to enhance transparency and reduce information asymmetry on financial products being offered by different regulated entities, thereby empowering borrowers to make informed financial decisions. Accordingly, discussion on what is APR and how merchant subvention should be disclosed holds precedence.

Definition of APR

In India, as per Key Facts Statement (KFS) for Loans & Advances the term APR ”is the annual cost of credit to the borrower which includes interest rate and all other charges associated with the credit facility”. The said circular covers retail loans, MSME term loans, digital loans, MFI loans, and all loans extended by banks to individuals. Our FAQs on the said circular can be read here.

Further, as per Para 2(a)(iii) of the Display of information by banks APR allows customers to compare the costs associated with borrowing across products and/ or lenders. Further, through the circular dated September 17, 2013 the RBI emphasised that it is important to ensure that the borrowers are fully aware of associated benefits, with emphasis on indiscriminately passing on such benefits without altering the Rate of Interest (RoI). To address this, the RBI directed that when discounts are provided on product prices, the loan amount sanctioned should reflect the discounted price, rather than adjusting the RoI to incorporate the benefit.

The Consumer Credit (Disclosure of Information) Regulations 2010, which is a UK regulation defines the term APR as “annual percentage rate of charge for credit xx…. and the total charge for credit rules”. Further, as per the regulation, APR helps the borrowers compare different offers.

The Truth in Lending (Regulation Z) defines APR in the case of closed-end credit as a “measure of the cost of credit, expressed as a yearly rate, that relates the amount and timing of value received by the consumer to the amount and timing of payments made”.

Components of APR

I. India

In accordance with the definition as provided under the Key Facts Statement (KFS) for Loans & Advances APR includes the following:

- Rate of interest

- Associated charges

- Processing fee

- Valuation fee

- Other non-contingent charges

c. Third-party service provider fees/charges (if collected by lender on behalf of third-party)

- Insurance charges

- Legal charges

- Other charges of similar nature

However, excluding contingent charges like penal charges, foreclosure charges, etc.

The intent is to have simple transparent, and comparable (STC) terms of the loan communicated to the customer upfront and hence, an illustrative example for the computation is provided. The illustration includes all charges that the RE levies.

II. United Kingdom

In accordance with the definition provided, APR refers to the annual percentage rate of charge for credit along with the total charge for credit as provided under credit rule As per FCA handbook, the total charge for credit, applicable to an existing or potential loan agreement, encompasses the “comprehensive cost” incurred by the borrower.

“Comprehensive cost” includes all pertinent expenses such as interest, commissions, taxes, and any other associated fees that are obligatory for the borrower to be paid in conjunction with the loan agreement.

The FCA handbook further specifies that the total cost of credit includes fees to credit brokers, account maintenance expenses, payment method costs, and ancillary service fees. However, the total cost of credit to the borrower must not take account of any discount, reward (including ‘cash back’) or other benefit to which the borrower might be entitled, whether such an entitlement is subject to conditions or otherwise.

To summarise, the components of APR as per UK regulations are:

- Rate of Interest

- Commission and taxes

- Fees/Charges payable by borrower to agents

- Expenses associated with maintaining loan account

- Costs linked with means of payment

- Costs associated with ancillary services

Further, the following shall not be considered while computing the APR and hence, will be disclosed separately:

- Discounts, cashback incentives;

- Contingent charges

III. USA

Section 107(a)(1)(A) of the Consumer Credit Protection Act outlines how to calculate the annual percentage rate (APR) for credit facilities other than open-ended ones. The APR is the rate that, when applied to the unpaid balance of the loan, equals the total finance charge spread out over the loan’s term. This means that the APR represents the finance charge stretched over the entire duration of the loan. Finance charges, as defined by the Act, include various fees like interest, service charges, origination fees, credit investigation fees, insurance premiums, and other related charges.

Hence, the components of APR as per USA include:

- Rate of interest;

- Discounts;

- Associated charges

- Service fees;

- Fees associated with loan origination

- Charges for credit investigation or reports

d. Third-party service provider charges (such as insurance charges)

Comparative analysis

Upon examining international practices, it becomes evident that the APR encompasses more than just the rate of return; it also incorporates additional charges, often in the form of finance charges, which are annualised over the tenure of the loan. To summarise and consolidate the various laws discussed above, the following factors are considered in determining the APR:

- Rate of Interest;

- Service charges;

- Fees associated with loan origination;

- Charges for credit investigation and reports;

- Charges for mandatory credit-related insurances, when not separately disclosed in the Key Facts Statement (KFS);

- Expenses related to maintaining the account

However, certain elements which are not included in the calculation of APR:

- Contingent charges;

- Discounts applied to the interest rate.

While US law suggests factoring in discounts when calculating the APR, the stance established by the RBI is clear that: discounts cannot be incorporated when declaring the APR- as the same would be deceptive and shall not disclose the actual bifurcation of cost. Similarly, the perspective under UK law aligns with this stance to separately disclose the merchant discount and deduct it from the APR.

Regulatory concerns

The RBI addressed regulatory concerns pertaining to zero percent loans facilitated by merchant subvention through its circular dated September 17, 2013. A key focus was ensuring borrowers full awareness of associated benefits, with emphasis on indiscriminately passing on such benefits without altering the Rate of Interest (RoI). To address this, the RBI directed that when discounts are provided on product prices, the loan amount sanctioned should reflect the discounted price, rather than adjusting the RoI to incorporate the benefit.

Disclosure of merchant subvention by lenders

As discussed, the rate of interest is a part of the Annual Percentage Rate (APR), which is a measure used by borrowers to compare similar products from different lenders. If the lender changes the rate of interest, it affects the entire APR, making it difficult for customers to compare different loan products. It is important to understand that whether or not there’s a merchant subvention, the rate of return for the lender remains unchanged, hence the APR irrespective of there being any merchant subvention should also remain unaltered.

The RBI through its circular dated September 17, 2013 notified certain “pernicious” practices being followed by banks regarding merchant subvention, whereunder it had provided a specific way of disclosing the discount, which directed that when discounts are provided on product prices, the loan amount sanctioned should reflect the discounted price, rather than adjusting the RoI to incorporate the benefit. We have aimed to understand the requirement of by RBI via an example below:

Assume a lender offers a loan of Rs. 100,000 for 6 months to someone without charging any interest. However, the lender only gives Rs. 95,000 to the merchant, and the remaining Rs. 5,000 is covered by the merchant i.e., the interest component of the loan is recovered from the merchant. The lender still expects the borrower to repay Rs. 100,000. So, to show the true cost in the APR, the lender should disclose the actual amount lent, which is Rs. 95,000, instead of the full Rs. 100,000. Additionally, the lender should include the interest rate the lender is effectively earning, on Rs 95000. This transparency helps customers understand exactly what they’re paying, making it easier to compare different loan options and lenders.

The circular as mentioned above was directed specifically for banks, however, NBFCs should also be guided by the same principles. There could be another method of disclosing the discount provided by the merchant. For instance, considering the above scenario, let say, the lender provides a loan of Rs. 1,00,000 and the merchant provides a subvention of Rs. 5,000. In this case, the APR is disclosed considering the subvention received from the merchant. Accordingly, the lender shows the loan to be Rs.1,00,000 and the interest of Rs.5000 is shown as a discount to the borrower, which has been recovered from the merchant. Even though the disclosure is being done for the subvention amount, this method does not depict the actual IRR of the lender. .

Note, however, that the APR computation in the two approaches will be different. The Table below shows the two APRs:

| Particulars | First option | Second option |

| Cost of the asset | 100000 | 100000 |

| Less: Discount | 5000 | |

| Net cashflow of the lender | 95000 | 100000 |

| Interest on the cashflow for 6 months(IRR computed on monthly intervals) | 10.30% | 10% |

| Amount of interest | 5000 | 5000 |

| Less: Discount | -5000 | |

| Amount paid by the borrower | 100000 | 100000 |

As may be noted from the above computation, the first option, computing the APR on a loan size of Rs 95000 shows the APR as 10.30%, while the second approach makes a simple interest computation for 6 months @ 10%. The second approach shows a lower APR than the actual yield.

Accounting

As per IND AS 109 Effective Interest Rate (EIR) has been defined as “The rate that exactly discounts estimated future cash payments or receipts through the expected life of the financial asset or financial liability to the gross carrying amount of a financial asset or to the amortised cost of a financial liability. When calculating the effective interest rate, an entity shall estimate the expected cash flows by considering all the contractual terms of the financial instrument (for example, prepayment, extension, call and similar options) but shall not consider the expected credit losses. The calculation includes all fees and points paid or received between parties to the contract that are an integral part of the effective interest rate,transaction costs, and all other premiums or discounts”.

The definition states that the calculation of EIR will include fees and points paid or received between the parties to the contract that are an integral part of the effective interest. While in normal course, this should refer to the cashflows emanating from the contract between the lender and the borrower. But in the present case, if only the cash flows between the lender and borrower is considered, it will give an EIR of 0%, indicating that the lender is not earning from the transaction, which is not the true picture. The subvention from the third party is an essential element in the entire scheme of things, it is through this the lender is recovering its income. Therefore, in the present context, a wider meaning should be ascribed to expression parties to the contract that are an integral part of the effective interest; and subvention received from third parties should also be considered for the purpose of determining the effective interest rate and the gross carrying amount of the loan.

The essence of the accounting definition is that cashflows that are “integral part” of the credit facility are included in EIR computation. While the subvention is paid by a third party and not a party to the contract, but it cannot be contended that the subvention is not an integral part of the loan. Taking such a view would lead to an impracticality showing the loan as having zero EIR.

Conclusion

The lure of zero percent interest rate loans is increasingly being used by vendors and lenders, in the realm of personal finance. However, it is crucial to understand the nuances and implications associated with such loans, particularly those facilitated through merchant subvention arrangements. Regulatory concerns have arisen regarding the transparency and fair disclosure of these loans, particularly in ensuring that the actual cost of credit is accurately represented to consumers. Distorting the interest rate structure compromises transparency and hampers informed decision-making by borrowers.

The components of the APR vary across different jurisdictions but universally include factors such as the rate of interest, associated charges, fees, and expenses related to the loan. However, discounts and contingent charges are typically excluded from the APR calculation. To uphold fair lending practices and ensure transparency, lenders must disclose the true cost of credit, including any merchant subvention arrangements, without altering the APR. This transparency empowers consumers to make informed choices and fosters trust in the financial system. A half truth reminds one of the Mahabharat anecdote of “Ashwatthama is dead”, suppressing whether it was elephant or man.