Representation on the draft Amendment Directions for exemption from registration to eligible NBFCs

Loading…

Loading…

Loading…

Loading…

Loading…

Loading…

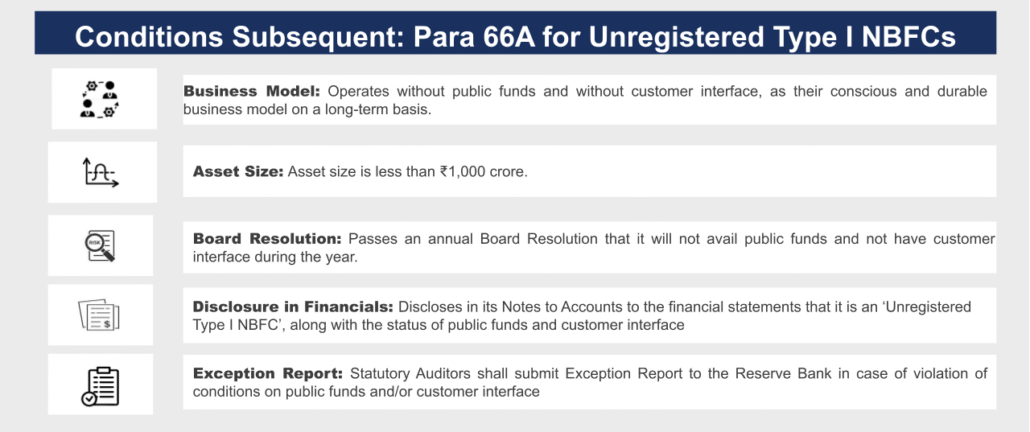

The RBI’s proposed relief to exempt pure investment companies from exemption from regulation is not a cakewalk but a hurdle race. It is not an exemption that comes in auto mode; you need to earn the right to be exempt. Some of the important pre-conditions that the RBI has proposed are:

| Type of NBFC | Options Available |

| NBFCs holding Type I Registration as on April 1, 2026 | Option 1: Apply for deregistration Option 2: Continue to remain as Type I NBFC |

| Entities that fulfil the conditions for Unregistered Type I NBFC, after April 1, 2026 | Option 1: Satisfy the conditions under 66A and remain unregistered [see box on Conditions Subsequent] Option 2: Apply for registration as Type I NBFC |

| NBFCs not having a customer interface and public funds and having an asset size below ₹1000 crores, but not registered as Type I | Option 1: Apply for deregistration Option 2: Apply for registration as Type I NBFC to avail regulatory exemptionOption 3: Maintain status quo |

| NBFCs not having a customer interface and public funds and having asset size above ₹1000 crores, but not registered as Type I | Option 1: Apply for registration as NBFC Type I Option 2: Apply for registration as NBFC Type II, in case of changes in business model |

Several NBFCs that have been registered with the RBI before the concept of Type 1 was introduced in 2016 may not have the CoR as a Type 1 NBFC in spite of the fact that as on date they don’t have access to public funds nor any customer interface. Such an NBFC with an asset size less than ₹1000 crores will still have an option to apply for deregistration, subject to the satisfaction of the conditions prescribed. However, such NBFCs in case they decide to maintain the status quo will not be eligible for the regulatory exemption available to Type 1 NBFCs.

If an entity carries investment activity with owned funds, within a limit of ₹1000 crores, does it need RBI registration? The answer seems to be – no. Such a company obviously does not have to go through the rigour of seeking registration first, and then qualifying for an exemption.

The company in question still has to satisfy the exemption conditions; and the auditor will need to give an exception report. The meaning of exception report is that if there is a breach of any of the conditions of exemption, or there is any breach of any other provisions of the law, the auditor shall be required to make an exception report.

Notably, CARO Order also requires auditors to comment on adherence to RBI regulations, which, in future, will include these conditions too.

Is the requirement of asset size being within ₹1000 crores based on stand-alone financial statements, or will the assets of companies within the group be aggregated, as is done for the purpose of determination of the middle layer status of companies?

It seems that the aggregation requirement is not there for the Type 1 exemption.

The basis for this is FAQ 13, which states as follows:

Q13. As per regulations of the Reserve Bank, total assets of all the NBFCs in a Group are consolidated to determine the classification of NBFCs in the Middle 11 Layer. What shall be the treatment given to ‘Type I NBFCs’ and ‘Unregistered Type I companies’ in this regard?

Ans: For aggregation purposes, the asset size of ‘Type I NBFCs’ shall be considered but asset size of ‘Unregistered Type I NBFCs’ shall not be considered. It is emphasized that ‘Type I NBFCs’ shall always be classified in Base Layer regardless of such aggregation.

Are the exemption conditions, that there is no access to public funds and no customer interface, merely a statement of intent, or must also be borne out by the conduct in any of the past 3 financial years? Looking at the definition in para 6 (14A), which reads “Not accepting public funds and not intending to accept public funds”, and likewise, “Not having customer interface and not intending to have customer interface”, it appears that the exemption conditions are both a statement of fact as well as intent. If one is negated by the fact, a mere statement of intent may not help.

However, assume there are isolated instances of intra-group loans taken or intra-group loans given. The transactions are not indicating a “business model”, at least the ones on the asset side. Are we saying that the breach of the conditions of “no public funds” and “no customer interface”, at any time during the last 3 years, will disentitle the exemption?

We do NOT think so. There are two reasons to say this:

In our view, since the deregistration application has to be made within September 30, 2026, the audited financials for FY 25-26 must have been prepared. Hence, the last three financial years that would be considered are FY 23-24, 24-25 and 25-26.

It is usually hard to get a relief from a regulator, as relief is seen as a prize that you earn. If the idea was based on the premise that what does not matter for the financial system, and is still being regulated, is a burden both for the regulator and for the regulated, there would have been a more welcoming approach to exemption. Specifically:

– Dayita Kanodia & Siddharth Pandey | finserv@vinodkothari.com

Budget 2026 proposed to introduce Total Return Swaps (TRS) for corporate bonds, purportedly as a measure for synthetic trading in corporate bonds. However, given the very slow pick up of credit default swaps, the much easier and globally prevalent version of credit derivatives, will the more esoteric TRS really make a difference? We explain what TRS is, how it differs from a CDS, give a sense of the global data on TRS as a part of OTC credit derivatives, and discuss how much the new measure will impact India’s bond market.

On February 6, RBI, in furtherance of the announcement in the Statement on Developmental and Regulatory Policies dated February 6, 2026, issued the draft revised Master Direction – RBI (Credit Derivatives) Directions, 2022. (‘Draft CD Directions’). The Draft CD Directions permit TRS to be issued to eligible persons.

India’s credit derivatives market has historically remained shallow, with hardly any transanctions involving credit default swaps. This has resulted in limited hedging options focused only on default risk and an absence of tools for transferring market and price risk.

This contrasts sharply with global trends. As of mid-2025, the notional outstanding volume of OTC derivatives exceeded USD 840 trillion, with credit derivatives, despite being smaller in absolute size than interest rate or FX derivatives, recording the fastest year-on-year growth at approximately 23%.

It may be noted that as of 1996, which is when credit derivatives had almost started emerging and gaining strength, TRS transactions were significant and took up almost 32% of the market share. However, the percentage of TRS dropped. Over time, CDSs overtook the position because CDSs are more definitive and limit the risks of the protection seller. In 2025, as per 118th edition of the OCC’s Quarterly Report on Bank Trading and Derivatives Activities based on call report information provided by all insured U.S. commercial banks and others, the TRSs had become a smaller segment representing 4.9 per cent of the credit derivative market.

In simple terms, a TRS swap transfers the entire volatility of returns of a reference asset from one party to another. TRS is a kind of derivative contract wherein the protection buyer agrees to transfer, periodically and throughout the term of the contract, the actual returns from a reference asset to the protection seller (“floating returns”), and the latter, in return, agrees to transfer returns calculated at a certain spread over a base rate (“fixed returns”) Total returns include the coupons, appreciation, and depreciation in the price of the reference bond. On the other hand, the protection seller will pay a certain base rate, say, risk free rate, plus a certain spread. The protection seller in the case of a TROR swap is also referred to as the total return receiver, and the protection buyer is similarly called the total return payer. The figure below illustrates the essential mechanics of a total return swap.

Impact of TRS

TRS swaps originate from synthetic equity structures, where economic returns of an asset are transferred without any actual investment in the underlying. The structure separates economic exposure from legal ownership. In a TROR swap, the economic impact is such that the total return receiver assumes the position of a synthetic lender to or investor in the bonds of the reference obligor, while the total return payer becomes a synthetic lender to the counterparty. Consider the illustration below:

Thus, the true impact of a TROR swap is the synthetic replacement of exposures. Consequently, the advantages of a TRS can be:

TRS structures have been used globally across a wide range of asset classes, including equities, bonds, loans, real estate and property interests, credit-linked notes, and portfolios or indices of such assets. Hence, a TRS is a credit derivative only when the reference asset is a credit asset, otherwise it is a generic total return derivative. The Draft CD Direction framework deliberately confines TRS usage to specified debt instruments in order to prevent synthetic funding and balance-sheet arbitrage.

| Aspects | CDS | TRS |

| Basic Definition | A credit derivative contract where a protection seller commits to pay the buyer in the event of a credit event. | A credit derivative contract where a payer transfers the entire economic performance of an asset to a receiver (protection seller). |

| Risk Transferred | Transfers only the credit risk associated with a specific obligation. The protection seller is only concerned with the risk of default or increase in credit spreads of the asset. That is, the reference transaction only shifts the risk of credit spreads | Transfers the total volatility of returns, including credit risk, interest rate risk, and market risk. The receiver gains exposure to all gains and losses (coupons, appreciation, and depreciation). |

| Cash Flow Mechanics | The buyer makes periodic premium payments to the seller until maturity or a credit event | Involves a periodic exchange of cash flow, the payer gives returns and appreciation; the receiver gives a benchmark rate + spread and depreciation. No fixed premium; the premium is inherent in the difference between actual returns and the agreed-upon spread |

| Synthetic Impact | Used primarily for credit insurance or hedging against specific default. | Used to synthetically replace the entire exposure of the parties, causing the receiver to assume the position of a synthetic lender to the reference obligation. |

Total Return Swaps can be categorized into several types based on their underlying assets and funding structures:

See further details on TRS in the book on Credit Derivatives and Structured Credit Trading by Mr Vinod Kothari

The Draft CD Directions permit the use of TRS while adding multiple safeguards to ensure that TRS functions strictly as a credit risk transfer instrument and not as a means of synthetic funding, balance-sheet arbitrage, or regulatory circumvention. The regulatory framework governs four key aspects:

Para 4.1.2(iii) of the revised Directions stipulates that at least one counterparty to every credit derivative transaction must be a market-maker. For this purpose, market-makers are defined to include

This requirement ensures that TRS transactions are intermediated by regulated entities with adequate risk management capabilities.

In alignment with this overarching requirement, the Draft CD Directions prescribe the following specific eligibility conditions for TRS:

In addition to prescribing eligible participants, the Draft CD Directions impose strict controls on the nature of reference entities and assets that may be used for TRS transactions. These controls are intended to ensure transparency, prevent regulatory arbitrage, and avoid the creation of complex or opaque synthetic exposures.

Reference entity:

A reference entity refers to the issuer whose credit risk and economic performance form the basis of the TRS contract. For TRS, the reference entity shall be a indian resident entity that is eligible to issue Reference assets under the Draft CD Directions.

By limiting reference entities to domestic issuers of eligible debt instruments, the framework ensures that TRS activity remains in the Indian corporate debt market, which was also the regulatory intent.

Reference assets:

A reference asset refers to the underlying corporate bond or debt instrument issued by the reference entity or an index of underlying debt instruments specified in a total return swap contract. The Draft CD Directions specify the following as eligible reference assets for TRS:

At the same time, the Directions expressly prohibit TRS on certain instruments, including asset-backed securities, mortgage-backed securities, credit-enhanced or guaranteed bonds, convertible bonds, and other hybrid or structured obligations. This exclusion reflects regulatory caution against layering derivatives on complex or credit-enhanced products that could obscure risk transfer.

Index-based reference assets

The Draft CD Directions also permit a TRS to reference an index, provided that:

Although such index based reference asset has been introduced for CDS and TRS, no such index for debt securities exists currently. Accordingly, such an index must be developed.

Para 4.5.1(ii) of the Draft CD Directions expressly provides that market participants shall not undertake credit derivative transactions, including Total Return Swaps, involving reference entities, reference obligations, or reference assets where such transactions would result in exposures that the participant is not permitted to assume in the cash market, or where they would otherwise violate applicable regulatory restrictions. This provision prevents the use of TRS to bypass exposure limits, concentration norms, sectoral caps, or investment restrictions applicable to the participants.

Additional safeguards for TRS used for hedging

Where a TRS is entered into for the purpose of hedging, the market-maker is required to ensure that the user satisfies the following conditions:

These safeguards reinforce the principle that hedging-oriented TRS must remain strictly co-terminous and proportionate to the underlying exposure, thereby avoiding over-hedging or speculations. Further, the Draft CD Direction specify that the settlement rules and standard documentation will be specified by shall be specified by the Fixed Income Money Market and Derivatives Association of India (FIMMDA), in consultation with market participants. However, the market participants are allowed to, alternatively, use a standard master agreement for credit derivative contracts.

Will this new instrument have an impact on bond markets in India? The first instance of guidelines on credit derivatives was issued in 2011; this failed to have any impact at all. Then, after the report of the Working Group, new Credit Derivatives Directions were issued in 2022. These also, at least based on anecdotal market information, have not had any significant traction at all.

CDS is much more standardised than TRS; as we have noted above, TRS is only 4.9% of the global credit derivatives market. Will the Indian market, which has not yet picked up credit spread trading in the form of CDS, delve into a far more esoteric TRS trade? Was it based on any reasoned or surveyed market feedback that this regulatory change was inspired? These questions, a priori, are difficult to answer. However, like a new flavour of ice cream, you never know until you try it.

Other Resources:

– Dayita Kanodia, Assistant Manager | finserv@vinodkothari.com

Holding Companies whose primary intent is to invest in their group companies have lately faced a paradox with respect to the requirement of registration as a Core Investment Company (CIC).

CICs are entities whose principal activity is the acquisition and holding of investments in group companies, rather than engaging in external investments or lending exposure outside the group. Para 3 of the Reserve Bank of India (Core Investment Companies) Directions, 2025 (‘CIC Directions’) prescribes the quantitative thresholds for classification of an NBFC as a CIC. In terms thereof, an NBFC that holds not less than 90% of its net assets in the form of investments in group companies, of which at least 60% is in equity instruments, is classified as a CIC and is required to obtain registration from the RBI, unless exempted.

Conceptually, a CIC is a sub-category of a Non-Banking Financial Company (NBFC) (para 3 of the CIC Directions), just like Housing Finance Companies, Micro Finance Institutions, etc. The threshold criteria that NBFCs are required to satisfy is the principal business criteria (PBC), pursuant to which at least 50% of the total assets of the entity must consist of financial assets and at least 50% of its total income must be derived from such financial assets.

The PBC has historically served as the foundational threshold for determining whether an entity is an NBFC. Once the entity satisfies this principal requirement of carrying out financial activity, the sub-category is to be determined based on its line of business, which, lately, has seen quite a varietty – fron tradtional variants such as investment and lending activities (ICC), to housing finance (HFC), to financing of receivables (Factoring companies), the more recent inclusions are account aggregators (AA), mortgage guarantee companies (MGCs), infrastructure finance compaies (IFC), etc. Each of these NBFCs first, and then they fall in their respective class. For instance, HFCs are a type of NBFCs that primarily focus on extending housing loans and hence, must have a minimum housing loan portfolio of 60% and an individual housing loan of 50%.

Accordingly, all categories of NBFCs must first be ascertained to be carrying out financial activities as their primary business, and thereafter, the specific product helps to determine the category. Consequently, holding companies or CICs should ideally also adhere to the 50-50 criteria first and thereafter meet the 90-60 criteria for CIC classification.

However, there is a common perception among the market participants that CICs, irrespective of meeting such PBC, in case they reach the 90-60 criteria, will be required to obtain registration as a CIC. Several news reports also note this perception.

This perception among the market participants that CICs are not required to adhere to the PBC criteria stems from para 17(3) of the CIC Directions, which explicitly provides that:

“CICs need not meet the principal business criteria for NBFCs as specified under paragraph 38 of the Reserve Bank of India (Non-Banking Financial Companies – Registration, Exemptions and Framework for Scale Based Regulation) Directions.”

It may be noted that the above-quoted provision, which has recently been made a part of the CIC Directions pursuant to the November 28 consolidation exercise, was earlier included in the FAQs released by RBI on CICs. FAQs are RBI staff views; whereas Directions or Regulations are a part of subordinate law; however, in the consolidation exercise, a whole lot of FAQs and circulars became a part of the Directions.

Going by the intent of the NBFC classification and categorisation, the above-quoted provisions seem more relevant for registered CICs, implying that CICs once registered need not meet the PBC on an ongoing basis. CICs predominantly hold investments in group companies and therefore satisfy the 90–60 thresholds, but often do not derive any financial income from such investments. Group investments, being strategic in nature, are rarely disposed of, and the dividend income from such investments depends on the dividend/payout ratio, which may be quite low. In several cases, such entities continue to earn income, say, by way of royalty for a group brand name. Even the slightest of non-financial income will seem to breach the PBC criteria, which may challenge the continuation of registration of the CIC as an NBFC. In order to redress this, the provision under para 17(3) of the CIC Directions provides that CICs need not meet the PBC criteria on an ongoing basis.

What is the basis of this argument? The definition of a CIC comes from para 3, which says as follows: “These directions shall be applicable to every Core Investment Company (hereinafter collectively referred to as ‘CICs’ and individually as a ‘CIC’), that is to say, a non-banking financial company carrying on the business of acquisition of shares and securities, and which satisfies the following conditions.” Para 17 (3) is a note to Para 17, which apparently deals with conditions of continued registration.

Given that CIC is a category of NBFC, it would be counter-intuitive to say that the regulatory requirement requires holding companies to go for registration as a CIC even if they do not meet the PBC for an NBFC. In fact, if an entity is not an NBFC because it fails the principality of its business, it would not even come under the statutory ambit of the RBI by virtue of section 45-IC.

Accordingly, without going by just the text of the regulations, in our view, considering the regulatory intent, the following could be inferred:

Other Resources:

– Team Finserv | finserv@vinodkothari.com

Loading…

Loading…

– Chirag Agarwal & Siddharth Pandey | finserv@vinodkothari.com

The framework for Integrated Ombudsman Scheme (IOS) constitutes a cornerstone of the RBI’s customer protection and grievance redressal mechanism across the financial sector. With the objective of providing customers a single, unified and accessible platform for redressal of complaints against Regulated Entities, the RBI introduced the Integrated Ombudsman framework.

The RBI has now introduced the Reserve Bank – Integrated Ombudsman Scheme, 2026 (“IOS 2026”), which supersedes the earlier Reserve Bank – Integrated Ombudsman Scheme, 2021 (“IOS 2021”). The new Scheme shall come into force with effect from July 1, 2026.

The IOS 2026 seeks to refine and reinforce the existing mechanism by expanding the scope of coverage, strengthening the powers of the Ombudsman, tightening procedural timelines, enhancing disclosure and reporting. The table below highlights and analyses the key changes introduced under IOS 2026 as compared to the IOS 2021, to enable stakeholders to assess the regulatory and operational impact of the revised framework.

| Provision | IOS 2021 | IOS 2026 | Analysis / Impact |

| Definition of “Customer” & “Deficiency in Service” | The term “Customer” was not defined. Limited definition for ‘Deficiency in Service’, largely linked to users/applicants of financial services. | ‘Customer’ means a person who uses, or is an applicant for, a service provided by a Regulated Entity. (Para 3(1)(h)) ‘Deficiency in Service’ now applicable across all services provided by Regulated Entities and not just restricted to financial services. (Para 3(1)(i)) | Broadens the scope of protection by covering all services offered by Regulated Entities, not just financial services. |

| Definition of “Rejected Complaints” | Not expressly defined | New definition introduced – complaints closed under Clause 16 of the Scheme. (Para 3(1)(o)) | Clarificatory in nature; definition is not used elsewhere in the Scheme |

| Power to Implead Other Regulated Entities | No explicit power | Ombudsman empowered to make other Regulated Entities a party to the complaint if such Regulated Entity has, by an act, negligence, or omission, failed to comply with any directions, instructions, guidelines, or regulations issued by the RBI. (Para 8(6)) | Expands investigative and adjudicatory powers of the RBI Ombudsman |

| Annual Report on Scheme Functioning | The Ombudsman was required to submit an annual report to the Deputy Manager of the RBI; however, the RBI was not obligated to publish it. | It has now been made mandatory for the RBI to publish an annual report on the functioning and activities carried out under the Scheme. (Para 8(7)) | Enhances transparency and public accountability of the Ombudsman framework |

| Interim Advisory | No express provision | Ombudsman expressly empowered, if deemed necessary and based on the circumstances of the complaint, to issue an advisory to the RE at any stage to take such action as may lead to full or partial resolution and settlement of the complaint. (Para 14(6)) | Enables interim reliefs/directions and more effective complaint handling. This would help in resolving disputes by settlement at any stage. IOS permits advisories i.e., communications from the Ombudsman advising REs to take actions for full or partial complaint resolution. Advisories are non-binding and serve as a pre-award tool to facilitate quicker settlements. |

| Principal Nodal Officer (PNO) – Change Reporting | Reporting obligation not specified | Any change in appointment or contact details of PNO must be reported to CEPD, RBI (prior to change or immediately post-change) (Para 18(2)) | Additional intimation requirement for regulated entities |

| Compensation – Consequential Loss | Capped at ₹20 lakh | Enhanced to ₹30 lakh (Para 8(3)) | Increases the limit of potential financial risk for Regulated Entities |

| Compensation – Harassment & Mental Anguish | Consolatory damages capped at ₹1 lakh | Increased to ₹3 lakh (in addition to other compensation) (Para 8(3)) | Compensation limit tripled |

| Limit on Amount in Dispute | No monetary cap | No change – still no limit (Para 8(3)) | Ombudsman continues to have wide jurisdiction irrespective of dispute value |

| Timeline for Filing Complaint | 1 year from RE’s reply; or 1 year + 30 days if no reply from RE | Complaint must be filed within 90 days from the expiry of the RE’s response timeline (30 days) or last communication, whichever is later. (Para 10(1)(g)) | Considerably tightens timelines; this would mean the customers must act swiftly |

| Guidance on Complaint Filing | Dispersed across the Scheme | Consolidated guidance provided in Part A of the Annexure along with Complaint Form. (Annex) | The guidance merely reiterates the points from the scheme that relate to admissibility of a valid complaint, but this is useful for the complainant as he will be aware of the complaint filing requirements and shall not be required to be thorough with the scheme itself |

| Modes of Filing Complaint | Specified the options to file a complaint through portal, email, or courier at CRPC. | Explicitly specified the email-ID of CRPC, and the address at which the complaint shall be couriered. (Para 6(2)) | Specification of the details for filing complaint |

| Data Consent in Complaint Form | No explicit consent requirement | Explicit consent for use of personal data mandatory. (Annex) | Aligns complaint process with evolving data protection and privacy standards |

| Categorisation of Complaints in complaint form | Limited classification | Detailed categorisation of complainant type and nature of complaint. (Annex) | Enables better routing, analytics, and faster resolution |

| Maintainability Check in Complaint Form | No upfront maintainability warning | Explicit note stating non-maintainable scenarios (court pending, advocate filing, etc.). (Annex) | Reduces frivolous filings and early-stage rejections |

| Appellate Authority | Executive Director in charge of concerned RBI department | Executive Director in charge of Consumer Education and Protection Department (CEPD) explicitly designated. (Para 3(1)(a)) | Clarificatory in nature |

| Introduced system-based validation | No such provision | Complaints received via portal, will undergo a system-based validation/check and will be rejected at the outset for being non-maintainable complaints. For the complaints received via e-mail and physical mode, CRPC will assess their maintainability under the Scheme. (Para 12(1)) | This would enhance the “gatekeeping” responsibility of the CRPC, which should speed up the process for valid complaints by weeding out inadmissible ones. |

Other Related Resources:

-Team Finserv | finserv@vinodkothari.com

On January 5, 2026, the RBI issued the Amendment Directions on Lending to Related Parties by Regulated Entities. Pursuant to this, changes were introduced to Reserve Bank of India (Non-Banking Financial Companies – Credit Risk Management) – Amendment Directions, 2026 (CRM Amendment Directions) and Reserve Bank of India (Non-Banking Financial Companies – Financial Statements: Presentation and Disclosures) Directions, Amendment Directions, 2026. Previously, Draft Directions were also issued on the subject. Our write-up on the draft directions can be accessed here.

The amendments under CRM Directions shall apply to all NBFCs, including Housing Finance Companies (HFCs) with regard to lending by an NBFC to its ‘related party’ and any contract or arrangement entered into by an NBFC with a ‘related party’. However, Type 1 NBFCs and Core Investment Companies shall not be covered under the applicability.

These amendments shall come into force on 1 April 2026. NBFCs may, however, choose to implement the amendments in their entirety from an earlier date.

In addition to complying with the provisions of the Amendment Directions, listed NBFCs shall continue to adhere to the applicable requirements of the Securities and Exchange Board of India (Listing Obligations and Disclosure Requirements) Regulations, 2015, as amended from time to time.

Grandfathering of existing arrangements: Existing RPTs that are not compliant with these amendments may continue until their original maturity. However, such loans, contracts, or credit limits shall not be renewed, reviewed, or extended upon expiry, even where the original agreement provides for renewal or review.

Any enhancement of limits sanctioned prior to 1st April 2026 shall be permitted only if they are fully compliant with these amendments.

| RPs under Amendment Directions | Whether covered in the Present Regulations |

| (A) Related Persons: These can be non-corporate | |

| a promoter, or a director, or a KMP of the NBFC or relatives of the said (natural) person | All other persons except the promoter was covered |

| Person holding 5% equity or 5% voting rights, singly or jointly, or relatives of the said (natural) person | No |

| Person having the power to nominate a director through agreement, or relatives of the said (natural) person | No |

| Person exercising control, either singly or jointly, or relatives of the said (natural) person | Yes |

| (B) Related Parties: These can be any person other than individual/HUF, and cover Entities where (A) | Covered Partially |

| is a partner, manager, KMP, director or a promoter | Promoter not covered |

| hold/s 10% of PUSC | Holds lower of (i)10% of PUSC and (ii)₹5 crore in PUSC |

| has single or joint control with another person | Yes |

| controls more than 20% of voting rights | No |

| has power to nominate director on the Board | No |

| are such on the advice direction, or instruction of which the entities are accustomed to act | No |

| is a guarantor/surety | Yes |

| is a trustee or an author or a beneficiary (where entity is a private trust) | No |

| Entities which are related to (A) as subsidiary, parent/holding company, associate or joint venture | Yes |

The definition of “Related Party” remains unchanged from that provided under the Draft Directions.

Further, a clarification have been added where an entity in which a related person has the power to nominate a director solely pursuant to a lending or financing arrangement shall not be regarded as a related party.

Under the Draft directions, the definition of a “related person” included group entities. However, pursuant to the Amendment Directions, group entities have been expressly excluded from the scope of “related person.” The provisions are specific for lending to directors, KMPs and their related parties. In the case of lending to entities such as subsidiaries and associates, the NBFC must adhere to the concentration norms as prescribed under the CRM Directions.

The definition of “Senior Officer” as provided under the erstwhile regulations (Para 4(1)(vii) of the Credit Risk Management Directions) has been omitted and, in its place, the concept of “Specified Employees” has been introduced. “Specified Employees” has been defined to mean all employees of an NBFC who are positioned up to two levels below the Board, along with any other employee specifically designated as such under the NBFC’s internal policy.

Under the erstwhile regulations, the term “Senior Officer” was given the same meaning as defined under Section 178 of the Companies Act, 2013. Thus, the terms Senior Officer included the following:

Practically, this change implies that one additional hierarchical level would now need to be designated as “Specified Employees”. Further, the specific inclusions that earlier applied under the Companies Act and the LODR Regulations i.e., functional heads under the Companies Act and CS and CFO under the LODR will no longer be automatically covered, unless they fall within two levels below the Board or are specifically designated as such under the NBFC’s internal policy.

‘Lending’ in the context of related party transactions would include funded as well as non-fund-based credit facilities to related parties. It may further be noted that investments in debt instruments of related parties are specifically included within the ambit of lending. Accordingly, the scope is not just restricted to loans and advances but includes all fund based and non-fund based exposures as well as investment exposures.

While lending to related parties, the following principles and provisions are to be followed by NBFCs:

The credit policy of the NBFC must contain specific provisions on lending to RPs. Mandatory contents of such policy will include:

Earlier, the policy requirement was specifically applicable in case of base layer NBFCs, but now the same has been made applicable for all NBFCs.

The CRM Amendment Directions also mandate prescribing board-approved limits for lending to RPs. Further, sub-limits will also have to be prescribed for lending to a single RP and a group of RPs. Here, a question may arise on what basis will the NBFC prescribe such limits? Such limits may be prescribed after considering the ticket size of the loans generally offered by the Company, to ensure the loans to RPs are aligned with the loan products for general customers. The limit may be specified as a percentage of the NOF of the NBFC, similar to the credit concentration limits.

NBFCs may extend credit facilities to related parties in accordance with their Board-approved credit policy. Any such lending must be within the board-approved limit prescribed for lending to RPs (including a single RP and a group of RPs).

Further, under the Amendment Directions (Para 13G of the CRM Amendment Directions), RBI has now clearly laid down materiality thresholds for such lending to related parties, including those to directors, senior officers, and their relatives. Lending above the prescribed materiality threshold should be sanctioned by the Board/Board Committee of the NBFC. (other than the Audit Committee).

It may be noted that earlier, for middle and upper layer NBFCs, any loans aggregating to ₹ 5 Crore and above were to be sanctioned by the Board/Board Committee. The materiality thresholds prescribed under the Amendment Directions are based on the layer of the NBFC, as follows:

| Category of NBFCs | Materiality Threshold |

| Upper Layer and Top Layer | ₹10 crore |

| Middle Layer | ₹5 crore |

| Base Layer | ₹1 crore |

| Layer of the NBFC shall be based on the last audited balance sheet.For loans, materiality threshold shall apply at individual transaction level | |

Can the power to sanction loans be delegated to the Audit Committee?

The CRM Amendment Directions have defined the Committee on lending to related parties which will mean a committee of the Board of the NBFC entrusted with sanctioning of loans to related parties. NBFCs may also identify any existing Committee, other than the Audit Committee, for this purpose.

Further, para 13I provides that,

However, a NBFC at its discretion, may delegate the above powers of lending beyond the materiality threshold to a Committee of the Board (hereafter called Committee) other than the Audit Committee of the Board

Accordingly, on a reading of the above, it seems that the power to sanction loans cannot be provided to the Audit Committee of the Board.

5. Quid Pro Quo Arrangements

The CRM amendment directions also provide that any arrangements which aim at circumventing the Amendment Directions will be treated as lending to RPs. Accordingly, any such arrangements involving reciprocal lending to related parties shall be subject to all the provisions of this direction.

Para 13J requires that Directors, KMPs and specified employees must recuse themselves from any deliberations or decision-making on loan proposals, contracts or arrangements that involve themselves or their related parties. This obligation also applies to all subsequent decisions involving material changes to such loans, including one-time settlements, write-offs, waivers, enforcement of security and implementation of resolution plans, to ensure independence and avoid conflicts of interest.

Details of exposure to related parties as per these Directions shall be disclosed in the Notes To Accounts pursuant to para 21(9A) of the Reserve Bank of India (Non-Banking Financial Companies – Financial Statements: Presentation and Disclosures) Directions, 2025 in the following format:

| (Amt in ₹ Crore) | |||

| Sr. No | Particulars | Previous Year | Current Year |

| Loans to Related Parties | |||

| 1 | Aggregate value of loans sanctioned to related parties during the year | ||

| 2 | Aggregate value of outstanding loans to related parties as on 31st March | ||

| 3 | Aggregate value of outstanding loans to related parties as a proportion of total credit exposure as on 31st March | ||

| 4 | Aggregate value of outstanding loans to related parties which are categorized as: | ||

| (i) Special Mention Accounts as on 31st March | |||

| (ii) Non-Performing Assets as on 31st March | |||

| 5 | Amount of provisions held in respect of loans to related parties as on 31st March | ||

| Contracts and Arrangements involving Related Parties | |||

| 6 | Aggregate value of contracts and arrangements awarded to related parties during the year | ||

| 7 | Aggregate value of outstanding contracts and arrangements involving related parties as on 31st March | ||

| Parameters | Existing Guidelines | Amendment Directions |

| Applicability | NBFC-BL- only policy requirement was prescribedNBFC-ML and above – threshold, approval and reporting was applicable | NBFCs in all layers, except Type 1 and CICs |

| Materiality Threshold/ Threshold for seeking board approval | NBFCs-BL- As per the PolicyNBFCs-ML- Rs. 5 croreNBFCs-UL- Rs. 5 crore | NBFCs-BL- Rs. 1 croreNBFCs-ML- Rs. 5 croreNBFCs-UL- Rs. 10 crore. Lending beyond the MT requires board or board committee approval (other than AC). |

| Board approved limits for lending to RPs | No such limit was required to be prescribed | Policy shall specify aggregate limits for loans towards related parties. Within this aggregate limit, there shall be sub-limits for loans to a single relatedparty and a group of related parties.Lending beyond the board approved limit, requires ratification by the Board/AC. |

| Monitoring | Loans and Advances to Directors less than ₹5 crores shall be reported to the Board. Further, all loans and advances to senior officers shall be reported to the Board. | Para 13K: Maintain and periodically update list of related persons, related parties, and loans to them. Para 13L: Annually report credit facilities to specified employees and relatives to the Board. Para 13M: Quarterly or shorter internal audit reviews on adherence to related party guidelines. Para 13N: Report deviations and reasons to the Audit Committee or Board. Para 13O: Products/structures circumventing Directions (reciprocal lending, quid pro quo) shall be treated as related party lending. |

| Policy Requirement | Only for NBFC-BL. NBFCs were required to prescribe a threshold beyond which the loans shall be required to be reported to the Board | Applicable for all NBFCs. |

| Recusal by interested parties | Directors who are directly or indirectly concerned or interested in any proposal should disclose the nature of their interest to the Board when any such proposal is discussed | Interested parties, including specified employees to recuse themselves |

| Disclosure under FS | Related Party Disclosure were specified as per format prescribed under Para 21(9) of Financial Statement Disclosures Directions | In addition to the earlier requirement, another format has been prescribed under Para 21(9A) with respect to details of exposures to related parties |

| Power to sanction loans to RPs | For NBFCs-BL: Only reporting is required; no board approval For NBFCs-ML and above: Board approval required for loans above the threshold. | For all NBFCs:Loans above materiality threshold shall be sanctioned by Board or delegated Committee (not Audit Committee) Loans below the threshold shall be sanctioned by appropriate authority as defined under the Policy. |

Our Other Resources:

– Vinod Kothari | finserv@vinodkothari.com

The new dispensation implemented from 5th December 2025 implies that lending business, obviously carried in the parent bank, needs to be allocated between the bank and the group entities so as to avoid overlaps. The bank will have to take its business allocation plan, at a group level, to its board, by 31st March 2026.

The RBI’s present move has certain global precedents. Singapore passed an anti-commingling rule applicable to banking groups way back in 2004, but has subsequently relaxed the rule by a provision referred to as section 23G of the Banking Regulations. However, the approach is not uniformly shared across jurisdictions.

We are of the view that as the decision works both at the bank as well as the NBFC/HFC level, the same has to be taken to the boards of the respective NBFCs/HFCs too.

Businesses which currently overlap include the following:

In our view, banks will have serious concerns in meeting their priority sector lending targets, unless they decide to keep priority sector lending business in the bank’s books. Priority sector lending is quite often much less profitable, and the NBFCs in the group are able to create such loans at much higher rates of return due to their delivery strengths or customer franchise. As to how the banks will be able to originate such loans departmentally, will remain a big question.

There are other implications of the above restrictions too:

In case of several non-lending products such as securities trading, demat services, etc., the approach may be easier. However, lending services constitute the bulk of any bank’s financial business, and group NBFCs and HFCs are also evidently engaged in lending. Hence, there may be a delicate decisioning by each of the boards on who does what. Note that this choice is not spasmodic – it is a strategic decision that will bind the entities for several years.

The factors based on which banks will have to decide on their business allocation may include:

Talking about pass through certificates, there is a complicated question as to whether the investment limits imposed by the 5th Dec. 2025 amendment on aggregate investments in group entities will include investment in pass through certificates arising out of pools originated by group entities. In our view, the answer is in the negative, as the investment is not originator, but in the asset pools. However, if the bank makes investment in the equity tranche or credit enhancing unrated tranches, the view may be different.

Banks are heading shortly in the last quarter of a year which is laden with strong headwinds. In this scenario, facing business allocation decisions, rather than business expansion or risk management, may be more challenging than it may seem to the regulators.

Other resources:

– Dayita Kanodia | finserv@vinodkothari.com

RBI on December 5, 2025 issued RBI (Commercial Banks – Undertaking of Financial Services) (Amendment) Directions, 2025 (‘UFS Directions’) in terms of which NBFCs and HFCs, which are group entities of Banks and are therefore undertaking lending activities, will be required to comply with the following additional conditions:

The requirements become applicable from the date of notification itself that is December 5, 2025. Further, it may be noted that the applicability would be on fresh loans as well as renewals and not on existing loans. The following table gives an overview of the compliances that NBFCs/HFCs, which are a part of the banking group will be required to adhere to:

| Common Equity Tier 1 | RBI (Non-Banking Financial Companies – Prudential Norms on Capital Adequacy) Directions, 2025 | Entities shall be required to maintain Common Equity Tier 1 capital of at least 9% of Risk Weighted Assets. |

| Differential standard asset provisioning | RBI (Non-Banking Financial Companies – IncomeRecognition, Asset Classification and Provisioning) Directions, 2025 | Entities shall be required to hold differential provisioning towards different classes of standard assets. |

| Large Exposure Framework | RBI (Non-Banking Financial Companies – Concentration Risk Management) Directions, 2025 | NBFCs/HFCs which are group entities of banks would have to adhere to the Large Exposures Framework issued by RBI. |

| Internal Exposure Limits | In addition to the limits on internal SSE exposures, the Board of such bank-group NBFCs/HFCs shall determine internal exposure limits on other important sectors to which credit is extended. Further, an internal Board approved limit for exposure to the NBFC sector is also required to be put in place. | |

| Qualification of Board Members | RBI (Non-Banking Financial Companies – Governance)Directions, 2025 | NBFC in the banking group shall be required to undertake a review of its Board composition to ensure the same is competent to manage the affairs of the entity. The composition of the Board should ensure a mix of educational qualification and experience within the Board. Specific expertise of Board members will be a prerequisite depending on the type of business pursued by the NBFC. |

| Removal of Independent Director | The NBFCs belonging to a banking group shall be required to report to the supervisors in case any Independent Director is removed/ resigns before completion of his normal tenure. | |

| Restriction on granting a loan against the parent Bank’s shares | RBI (Commercial Banks – Credit Risk Management) Directions, 2025 | NBFCs/HFCs which are group entities of banks will not be able to grant a loan against the parent Bank’s shares. |

| Prohibition to grant loans to the directors/relatives of directors of the parent Bank | NBFCs/HFCs will not be able to grant loans to the directors or relatives of such directors of the parent bank. | |

| Loans against promoters’ contribution | RBI (Commercial Banks – Credit Facilities) Directions,2025 | Conditions w.r.t financing promoters’ contributions towards equity capital apply in terms of Para 166 of the Credit Facilities Directions. Such financing is permitted only to meet promoters’ contribution requirements in anticipation of raising resources, in accordance with the board-approved policy and treated as the bank’s investment in shares, thus, subject to the aggregate Capital Market Exposure (CME) of 40% of the bank’s net worth. |

| Prohibition on Loans for financing land acquisition | Group NBFCs shall not grant loans to private builders for acquisition and development of land. Further, in case of public agencies as borrowers, such loans can be sanctioned only by way of term loans, and the project shall be completed within a maximum of 3 years. Valuation of such land for collateral purpose shall be done at current market value only. | |

| Loan against securities, IPO and ESOP financing | Chapter XIII of the Credit Facilities Directions prescribes limits on the loans against financial assets, including for IPO and ESOP financing. Such restrictions shall also apply to Group NBFCs. The limits are proposed to be amended vide the Draft Reserve Bank of India (Commercial Banks – Capital Market Exposure) Directions, 2025. See our article on the same here. | |

| Undertaking Agency Business | Reserve Bank of India (Commercial Banks – Undertaking of Financial Services) Directions, 2025 | NBFCs/HFCs, which are group entities of Banks can only undertake agency business for financial products which a bank is permitted to undertake in terms of the Banking Regulations Act, 1949. |

| Undertaking of the same form of business by more than one entity in the bank group | UFS Directions | There should only be one entity in a bank group undertaking a certain form of business unless there is proper rationale and justification for undertaking of such business by more than one entities. |

| Investment Restrictions | Restrictions on investments made by the banking group entities (at a group level) must be adhered to. |

Read our write-up on other amendments introduced for banks and their group entities here.

Other resources: