About time to unfreeze NPA classification and reporting

/2 Comments/in Banking Regulations, Housing finance, Indian Accounting Standards (Ind AS), Insolvency and Bankruptcy, NBFCs, RBI /by Vinod Kothari Consultants-Siddarth Goel (finserv@vinodkothari.com)

Introduction

The COVID pandemic last year was surely one such rare occurrence that brought unimaginable suffering to all sections of the economy. Various relief measures granted or actions taken by the respective governments, across the globe, may not be adequate compensation against the actual misery suffered by the people. One of the earliest relief that was granted by the Indian government in the financial sector, sensing the urgency and nature of the pandemic, was the moratorium scheme, followed by Emergency Credit Line Guarantee Scheme (ECLGS). Another crucial move was the allowance of restructuring of stressed accounts due to covid related stress. However, every relief provided is not always considered as a blessing and is at times also cursed for its side effects.

Amid the various schemes, one of the controversial matter at the helm of the issue was charging of interest on interest on the accounts which have availed payment deferment under the moratorium scheme. The Supreme Court (SC) in the writ petition No 825/2020 (Gajendra Sharma Vs Union of India & Anr) took up this issue. In this regard, we have also earlier argued that government is in the best position to bear the burden of interest on interest on the accounts granted moratorium under the scheme owing to systemic risk implications.[1] The burden of the same was taken over by the government under its Ex-gratia payment on interest over interest scheme.[2]

However, there were several other issues about the adequacy of actions taken by the government and the RBI, filed through several writ petitions by different stakeholders. One of the most common concern was the reporting of the loan accounts as NPA, in case of non-payment post the moratorium period. The borrowers sought an extended relief in terms of relaxation in reporting the NPA status to the credit bureaus. Looking at the commonality, the SC took the issues collectively under various writ petitions with the petition of Gajendra Sharma Vs Union of India & Anr. While dealing with the writ petitions, the SC granted stay on NPA classification in its order dated September 03, 2020[3]. The said order stated that:

“In view of the above, the accounts which were not declared NPA till 31.08.2020 shall not be declared NPA till further orders.”

The intent of granting such a stay was to provide interim relief to the borrowers who have been adversely affected by the pandemic, by not classifying and reporting their accounts as NA and thereby impacting their credit score.

The legal ambiguity

The aforesaid order dated September 03, 2020, has also led to the creation of certain ambiguities amongst banks and NBFCs. One of them being that whether post disposal of WP No. 825/2020 Gajendra Sharma (Supra), the order dated September 03, 2020, should also nullify. While another ambiguity being that whether the stay is only for those accounts that have availed the benefit under moratorium scheme or does it apply to all borrowers.

It is pertinent to note that the SC was dealing with the entire batch of writ petitions while it passed the common order dated September 03, 2020. Hence, the ‘stay on NPA classification’ by the SC was a common order in response to all the writ petitions jointly taken up by the court. Thus, the stay order on NPA classification has to be interpreted broadly and cannot be restricted to only accounts of the petitioners or the accounts that have availed the benefit under the moratorium scheme. As per the order, the SC held that accounts that have not been declared/classified NPA till August 31, 2020, shall not be downgraded further until further orders. This relaxation should not just be restricted to accounts that have availed moratorium benefit and must be applied across the entire borrower segment.

The WP No. 825/2020 Gajendra Sharma (Supra) was disposed of by the SC in its judgment dated November 27, 2020[4], whereby in the petition, the petitioner had prayed for direction like mandamus; to declare moratorium scheme notification dated 27.03.2020 issued by Respondent No.2 (RBI) as ultra vires to the extent it charges interest on the loan amount during the moratorium period and to direct the Respondents (UOI and RBI) to provide relief in repayment of the loan by not charging interest during the moratorium period.

The aforesaid contentions were resolved to the satisfaction of the petitioner vide the Ex-gratia Scheme dated October 23, 2020. However, there has been no express lifting of the stay on NPA classification by the SC in its judgment. Hence, there arose a concern relating to the nullity of the order dated September 03, 2020.

The other writ petitions were listed for hearing on December 02, 2020, by the SC via another order dated November 27, 2020[5]. Since then the case has been heard on dates 02, 03, 08, 09, 14, 16, and 17 of December 2020. The arguments were concluded and the judgment has been reserved by the SC (Order dated Dec 17, 2020[6]).

As per the live media coverage of the hearing by Bar and Bench on the subject matter, at the SC hearing dated December 16, 2020[7], the advocate on behalf of the Indian Bank Association had argued that:

“It is undeniable that because of number of times Supreme Court has heard the matter things have progressed. But how far can we go?

I submit this matter must now be closed. Your directions have been followed. People who have no hope of restructuring are benefitting from your ‘ don’t declare NPA’ order.“

Therefore, from the foregoing discussion, it could be understood that the final judgment of the SC is still awaited for lifting the stay on NPA classification order dated September 03, 2020.

Interim Dilemma

While the judgment of the SC is awaited, and various issues under the pending writ petitions are yet to be dealt with by the SC in its judgment, it must be reckoned that banking is a sensitive business since it is linked to the wider economic system. The delay in NPA classification of accounts intermittently owing to the SC order would mean less capital provisioning for banks. It may be argued that mere stopping of asset classification downgrade, neither helps a stressed borrower in any manner nor does it helps in presenting the true picture of a bank’s balance sheet. There is a risk of greater future NPA rebound on bank’s balance sheets if the NPA classification is deferred any further. It must be ensured that the cure to be granted by the court while dealing with the respective set of petitions cannot be worse than the disease itself.

The only benefit to the borrower whose account is not classified NPA is the temporary relief from its rating downgrade, while on the contrary, this creates opacity on the actual condition of banking assets. Therefore, it is expected that the SC would do away with the freeze on NPA classification through its pending judgment. Further, it is always open for the government to provide any benefits to the desired sector of the economy either through its upcoming budget or under a separate scheme or arrangement.

THE VERDICT

[Updated on March 24, 2021]

The SC puts the final nail to almost a ten months long legal tussle that started with the plea on waiver of interest on interest charged by the lenders from the borrowers, during the moratorium period under COVID 19 relief package. From the misfortunes suffered by the people at the hands of the pandemic to economic strangulation of people- the battle with the pandemic is still ongoing and challenging. Nevertheless, the court realised the economic limitation of any Government, even in a welfare state. The apex court of the country acknowledged in the judgment dated March 23, 2020[8], that the economic and fiscal regulatory measures are fields where judges should encroach upon very warily as judges are not experts in these matters. What is best for the economy, and in what manner and to what extent the financial reliefs/packages be formulated, offered and implemented is ultimately to be decided by the Government and RBI on the aid and advice of the experts.

Thus, in concluding part of the judgment while dismissing all the petitions, the court lifted the interim relief granted earlier- not to declare the accounts of respective borrowers as NPA. The last slice of relief in the judgement came for the large borrowers that had loans outstanding/sanctioned as on 29.02.2020 greater than Rs.2 crores. The court did not find any rationale in the two crore limit imposed by the Government for eligibility of borrowers, while granting relief of interest-on-interest (under ex-gratia scheme) to the borrowers.[9] Thus, the court directed that there shall not be any charge of interest on interest/penal interest for the period during moratorium for any borrower, irrespective of the quantum of loan. Since the NPA stay has been uplifted by the SC, NBFCs/banks shall accordingly start classification and reporting of the defaulted loan accounts as NPA, as per the applicable asset classification norms and guidelines.

The lenders should give credit/adjustment in the next instalment of the loan account or in case the account has been closed, return any amount already recovered, to the concerned borrowers.

[1] http://vinodkothari.com/2020/09/moratorium-scheme-conundrum-of-interest-on-interest/

[2] http://vinodkothari.com/2020/10/interest-on-interest-burden-taken-over-by-the-government/#:~:text=Blog%20%2D%20Latest%20News-,Compound%20interest%20burden%20taken%20over%20by%20the%20Central%20Government%3A%20Lenders,pass%20on%20benefit%20to%20borrowers&text=Of%20course%2C%20the%20scheme%2C%20called,2020%20to%2031.8.

[3] https://main.sci.gov.in/supremecourt/2020/11127/11127_2020_34_16_23763_Order_03-Sep-2020.pdf

[4] https://main.sci.gov.in/supremecourt/2020/11127/11127_2020_34_1_24859_Judgement_27-Nov-2020.pdf

[5] https://main.sci.gov.in/supremecourt/2020/11127/11127_2020_34_1_24859_Order_27-Nov-2020.pdf

[6] https://main.sci.gov.in/supremecourt/2020/11162/11162_2020_37_40_25111_Order_17-Dec-2020.pdf

[7] https://www.barandbench.com/news/litigation/rbi-loan-moratorium-hearings-live-from-supreme-court-december-16

[8] https://main.sci.gov.in/supremecourt/2020/11162/11162_2020_35_1501_27212_Judgement_23-Mar-2021.pdf

[9] Compound interest burden taken over by the Central Government: Lenders required to pass on benefit to borrowers – Vinod Kothari Consultants

[10] Moratorium on loans due to Covid-19 disruption – Vinod Kothari Consultants; also see Moratorium 2.0 on term loans and working capital – Vinod Kothari Consultants

Scalar regulatory framework for the NBFC sector

/0 Comments/in NBFCs /by Vinod Kothari Consultants-Financial Services Division (finserv@vinodkothari.com)

RBI has issued the Revised Regulatory Framework for NBFCs, effective from October 1, 2022. Highlights of prescribed framework can be accessed at this link.

Introduction

Systemic risk of NBFCs has been an issue for discussion, specifically in India as there have been some major NBFC failures, and the issue of inter-connectivity between NBFCs and the rest of the financial sector became clearly evident[1]. The issue is not limited to India -globally, an annual publication of the Financial Stability Board, called Global Monitoring Report on Non-banking Financial Intermediation[2] has been drawing attention to the increasing relevance of non-banking financial intermediaries and the risk they pose.

The RBI had, in its Statement on Development and Regulatory Policies dated December 4, 2020[3], highlighted a need to review the regulatory framework in line with the changing risk profile of NBFCs. The NBFC sector has witnessed various changes in the regulatory framework in the past few years, making it more comprehensive. However, the tremendous growth in the sector combined with regulatory arbitrage enjoyed by the NBFCs is now leading to a systemic risk. Hence, the regulators have thought it necessary to tighten the regulatory norms for NBFCs holding a major chunk of market share.

In line with the aforesaid announcement, the RBI released a Discussion Paper on January 22, 2021[4] seeking inputs from industry participants. The following write-up analyses the major propositions made by the RBI.

Highlights of the New Regulatory Framework

- 4 layers of regulatory intensity – progressively from bottom – BL, ML, UL, and TL, Base layer (BL) to be systematically non-significant entities, with light touch regulation. Some entities like Type 1 NBFCs (those without public interface or public funds) will always remain in the Base layer, seemingly irrespective of size. ML to consist of the systemically important NBFCs. From ML, 20-25 entities to be selected for tighter supervision, based on indicia of higher systematic risk. TL is empty by default, but to be populated only on exercise of supervisory discretion for extreme risks.

- Monetary threshold for systematic significance to be revised upwards from Rs 500 crores to Rs 1000 crores

- Aims at eliminating regulatory arbitrage at Layer 2 (ML) and above; seeks to align regulatory framework at ML with banks.

- Layer 3 (UL) is a new regulatory layer; regulations expected to be at par with banks.

- UL classification is not something that would take the NBFC by surprise; the decision to be put into the category will be communicated in advance with an opportunity to manoeuvre and come out the classification

- Entry-point requirement for new NBFC registrations to be increased 10 times, from Rs 2 crores to Rs 20 crores. Existing NBFCs to be given a timeframe, say, 5 years to measure up.

- NPA norms for BL NBFCs (currently, the NSI category) to be made 90 days instead of 180 days as of now

- At least one of the directors of the NBFCs to be a person with retail lending experience.

- ICAAP to be applicable to NBFC-ML and above.

- Auditor rotation after 3 years, appointment of a Chief Compliance Officer, managerial compensation controls, and several disclosure requirements to be imposed on ML entities.

- Concentration limits: Board-imposed caps on sectoral exposure; IPO financing limits, self-imposed real estate exposure – proposed for ML entities

- Core Banking Solution be adopted by NBFCs with 10 or more branches

- Upper Layer to consist of 25-30 entities selected from a sample of about 50 entities, based on scoring methodology, indicating distinctive systemic risk. 9% Common Equity Tier to be prescribed for these entities. Additionally, leverage limits may also be imposed.

- Differential provision for standard assets to prescribed for UL entities

- Mandatory listing, managerial remuneration controls, etc to be prescribed for UL entities

- Top layer to be similar to protective framework in case of banks: Higher capital charge, capital conservation buffer

Regulatory arbitrage: The concern behind present regulatory proposal

The operational flexibility provided to NBFCs has enabled them to assume a scale that would potentially impact systemic stability. In recent years, the regulator has identified structural arbitrage and prudential arbitrage between banks and NBFCs. While the former emanates from differences in legislative and licensing framework like net owned funds, branch approval requirements etc., the latter is concerning CRAR, prescribed leverage, liquidity guidelines etc.

There also exists some relaxation in corporate governance and disclosure norms for NBFCs in comparison to banks such as instructions on compensation policy for WTD/CEOs/Risk Control Staff and most of SCB being listed and thus abiding by the listing requirement.

NBFCs have become more interconnected with the financial system. Linkages are due to the substantial exposure that banks have in NBFCs. As per the Financial Stability Report of January 2021, NBFCs were the largest net borrowers of funds from the financial system. The gross payables and receivables stood around ₹9.37 lakh crore and ₹0.93 lakh crore as at end-September 2020.[5] More than half of this funding was supported by scheduled commercial banks (SCBs) followed by Asset Management Companies-Mutual Funds (AMC-MF) and Insurance Companies. Further the Discussion Paper noted that there are seven NBFCs (including HFCs) each having asset size exceeding 1 lakh crore and above.

The unconstrained growth of the NBFC sector in addition to the lenient regulatory framework within an interconnected financial system may sow the seeds of systemic risk. In the present scenario, failure of any large and deeply interconnected NBFC is capable of transmitting shocks into the entire financial sector and causing disruption even to the operations of the small and mid-sized NBFCs.

Classification of NBFCs by scale of activities, risks and size

The proposed framework provides for the regulation on scale based approach. This essentially means that regulatory and supervisory resources are to be more focused on the entities which have become too-big-to-fail (TBTF) owing to their systemic interconnectedness with other financial market participants. The degree of regulation is to be based on ‘principle of proportionality’. The three triggers of scale based regulation are:

- Risk perception: This parameter is based on size, leverage and interconnectedness of the NBFC with market participants in terms of prescribed threshold.

- Size of operations: The size of the balance sheet of an NBFC beyond a certain prescribed high threshold would be an important independent factor in determination of regulation.

- Nature of activity – Just by performing financial activity cannot give rise to systemic risk. Like Type 1 NBFCs which do not access public deposits and neither have customer interfaces are to be regulated with light touch. The essence of such form of NBFCs is that the financial activity is being carried out by net-owned funds. However some activities are regarded as high risk owing to their systemic connectivity and business model. The draft paper categorises NBFC-HFC, IFC, IDF, SPD and CIC as they are interconnected with other financial institutions while performing credit intermediation.

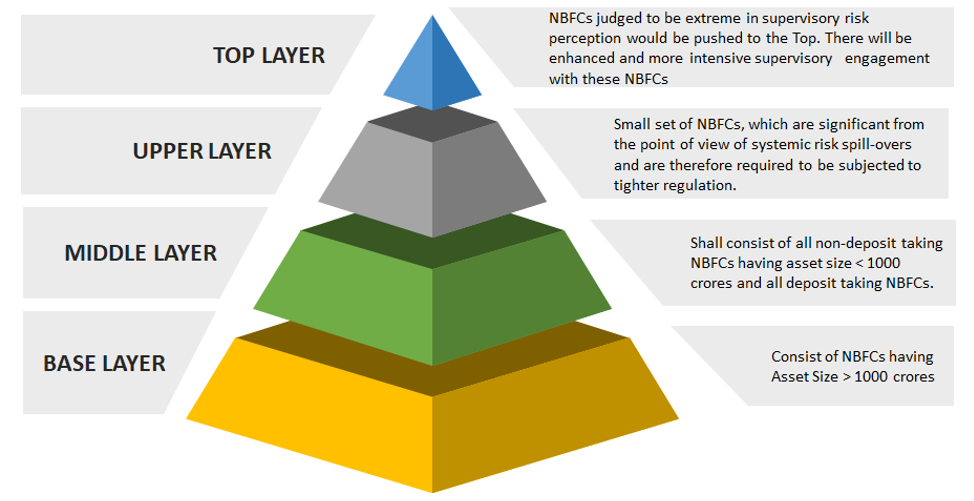

The RBI has proposed a scale-based four-layered structure regulatory framework–viz. Base Layer (NBFC-BL), Middle Layer (NBFC-ML), Upper Layer (NBFC-UL) and Top Layer. The classification of layers is made commensurate to the regulatory intervention required- i.e. the base layer having the least regulatory intervention and the intervention increasing as the one moves up the pyramid. The proposed categorisation/classification as provided in the discussion paper is summarized in the fig below.

Interestingly, CICs are poised to be put under greater scrutiny- this is possibly the regulatory reaction to a recent NBFC default. CICs are proposed to be regarded as Middle Layer NBFC (NBFC-ML) along with NBFCs currently classified as systemically important NBFCs (NBFC-ND-SI), deposit-taking NBFCs (NBFC-D), HFCs, IFCs, IDFs, SPDs. Though CICs and SPDs will fall in the Middle Layer of the regulatory pyramid, the existing regulations specifically applicable to them, will continue to apply. However, a pertinent question for discussion would be whether the activity-based classification of NBFC-AA, P2P, NOFHC in Lower Layer and NBFC-HFC, IFC, IDF, CIC and Standalone Primary Dealers in Middle Layer justified.

Increased NOF & harmonisation of NPA recognition

Further, NOF is proposed to be raised to Rs. 20 crores. Further, in order to ensure a smooth transition, a well-defined timeline will be prescribed by the RBI for existing NBFCs, spanning over a period of, say, five years. For new registrations, the higher NOF norms will get implemented immediately on the issue of instructions.

NPA recognition based on 90 DPD will be extended to all NBFCs including those which are not systemically important.

Recognition of NBFCs in Upper Layer

NBFC categorisation is based on annual review. The paper recognises two parameters; quantitative and qualitative:

- The quantitative parameters will have 70% weightage.

- The qualitative parameters will have 30% weightage.

The table below represents quantitative and qualitative parameters as proposed:

| Parameter | Sub-parameter | Sub weight | Weights |

| Quantitative Parameters (70%) | |||

| Size & Leverage | Size: Total exposure (on-and off-balance sheet)

Leverage: total debt to total equity |

20+15 | 35 |

| Interconnectedness | i) Intra-financial system assets:

– Lending to FIs – Securities of other FIs – Mark to market REPO – OTC derivatives

ii) Intra-financial system liabilities

– Borrowings from FIs – Marketable securities issued by finance company to FI – Mark to market OTC derivative with FIs iii) Securities outstanding (issued by NBFC) |

10

10

5 |

25

|

| Complexity | i) Notional amount of OTC derivatives

– CCP centrally – Bilateral OTC

ii) Trading and available for sale securities |

5

5 |

10 |

| Qualitative Parameters/Supervisory inputs (30%) | |||

| Nature and type of liabilities | – Degree of reliance on short term funding

– Liquid asset ratios – Callable debts – Asset backed funding Vs. other funding – Asset liability duration and gap analysis – Borrowing split (secured debt, CCPS, CPs, unsecured debt) |

10 | 30

|

| Group Structure | – Total number of entities

– Total number of layers – Total intra-group exposure |

10 | |

| Segment Penetration | Importance of NBFC as a source of credit in a specific segment or area | 10 | |

The scoring will be done on a sample basis, by dividing the individual NBFCs amount by the aggregate sum of all the indicators in the sample. The score for each category will be converted into basis points and the overall systemic significance score will be based on the relative importance of the NBFC compared with other NBFCs in the sample.

The sample criteria for the purpose of above parameter based measurement is to be as follows:

- Excluding the top 10 NBFCs (based on asset size) as they will automatically fall in upper layer regulation.

- The sample will include next 50 NBFCs based on total exposure (including off balance sheet)

- NBFCs designated as NBFC-UL in previous year

- NBFCs added to sample by supervisors judgement

For leverage calculation the individual score of NBFC is to be divided by average leverage of the sample. A NBFC-UL will be subjected to enhanced regulatory requirements similar to that of banks at least for a period of four years from its last appearance in the category, even where it does not meet the parametric criteria in the subsequent year.

NBFCs in Base Layer

The base layer would cover NBFCs with asset size upto Rs 1000 crores. The major propositions for this layer are provided in the table below:

| Proposals for NBFCs in Base Layer | |

| 1. | The current regulations require NPA classification of the asset having more than 180 DPDs the same is proposed to be reduced to 90 DPDs in order to bring it in sync with the regulatory guidelines for other classes of NBFCs |

| 2. | The board shall be required to have –

(i) Adequate experience and educational qualification (ii) At least one of the directors should have experience in retail lending in a bank/NBFC |

| 3. | For the Risk Management Committee-

(i) Overall role and responsibilities to be laid out, and (ii) Composition could be Board or Executive level as to be decided by the Board |

| 4. | The regulations for sale of stressed assets shall be made at par with banks once guidelines are finalized |

| 5. | Additional disclosures on type of exposures, related party transactions, customer complaints shall be prescribed |

NBFCs in Middle Layer

Several new regulatory requirements are proposed for this category in addition to the proposals for the base layer. There are no changes proposed in capital requirements for NBFC-ML.

| Proposals for NBFCs in Middle Layer | |

| 1. | Board approved policy taking into account all risks for Internal Capital Adequacy Assessment shall be required. |

| 2. | The extant credit concentration limits prescribed for NBFCs for lending and investment is proposed to be merged into a single exposure limit of 25% for single borrower and 40% for group of borrowers anchored to Tier 1 capital instead of Owned Funds |

| 3. | Compulsory Rotation of auditors shall be applicable- After completion of continuous audit tenure of three years, Auditors shall not be eligible for re-appointment for a period of six years (two tenures) |

| 4. | i) Appointment of a functionally independent Chief Compliance Officer.

ii) Additional Corporate Governance and Disclosure Requirements, including requirement for Secretarial Audit. |

| 5. | It has been proposed that no KMP of an NBFC shall be allowed hold office in any other NBFC-ML or NBFC-UL or subsidiaries, further, an Independent Director cannot be director in more than two NBFCs (NBFC-ML and NBFC-UL) at the same time |

| 6. | Board approved internal limits and adequate disclosures would be required for exposure to sensitive exposures and Dynamic vulnerability assessment by NBFCs shall be required. Sub-limit within the commercial real estate exposure ceiling should be fixed internally for financing land acquisition

|

| 7. | Restrictions on grant of loans and advances for/to the following:

(a) buy back of shares/ securities (b) activities leading to Ozone Depleting Substances (c) Directors and relatives of directors (d) Officers and relatives of Senior Officers (e) Real Estate – only where project approvals other permissions are in place. |

| 8. | The IPO financing by NBFCs shall be capped at Rs.1 crore. There is no limit prescribed for NBFCs at present, while there is a limit of Ts. 10 lakh for banks for IPO financing. |

| 9. | Mandatory for NBFCs with more than 10 branches to have Core Banking Solution for NBFCs |

NBFCs in Upper layer

In addition to the regulations applicable to NBFC-ML, a set of additional regulations will apply to NBFC-UL, they are:

| Proposals for NBFCs in Upper Layer | |

| 1. | CET 1 may be prescribed at 9% within the Tier I capital

In addition to the CRAR requirements, NBFCs will also be subjected to a leverage requirement |

| 2. | Differential Provisioning being similar as banks for standard assets to be made applicable |

| 3. | For Concentration norms-

(i) Large Exposure Framework (LEF) as applicable to banks with suitable modification will apply (ii) Transition time for implementation |

| 4. | Corporate Governance norms to be similar lines as applicable for Private Sector Banks. Additional governance regulations such as specifying qualification of board members, providing detailed disclosure on group companies including consolidated financial position and details of related party transactions. |

| 5. | Adequate phase-in-time for mandatory listing to be provided. However, disclosure requirements will kick in earlier than actual listing within the broad implementation plan for NBFC-UL |

| 6. | Removal of Independent Director shall require supervisory approval |

NBFCs in Top Layer

The top layer is currently empty and will get populated in case RBI takes a view that there has been an unsustainable increase in the systemic risk spill-overs from specific NBFCs in the Upper Layer. NBFCs in this Layer will be subject to higher capital charge, including Capital Conservation Buffers. There will be enhanced and more intensive supervisory engagement with these NBFCs.

Monetary threshold for systemically important NBFCs

Asset size of Rs 500 crores was stipulated a long time back for distinguishing between SI and NSI NBFCs, that is on November 10, 2014. The limits were in line with recommendations made by the Working Group on Issues and Concerns in the NBFC Sector, chaired by Smt. Usha Thorat.

After more than 6 years, the RBI proposes to increase the threshold from Rs 500 crores to Rs 1000 crores.

The inherent sense of reservation in this measure is itself evident from the data that the RBI has shared – that the number of NSI companies will go up from 9133 to 9209. That is, merely 76 companies will be taken out of the SI classification and put into BL category.

10-fold jump in entry point net worth requirement

If some people familiar with the evolution of regulatory framework for NBFCs may recall, the NOF requirement for NBFCs was Rs 25 lacs in 1990s. Then, it was increased to Rs 2 crores. The regulator is now proposing to increase the same to Rs 20 crores – a 10 fold increase. The underlying rationale is to have a stronger entry barrier, and to ensure that NBFCs have the initial capital for investing in technology, manpower and establishment. However, this sharp hike in entry point requirement will keep smaller NBFCs out of the fray. Smaller NBFCs, particularly those with geographical or sectoral focus, have been doing a useful job in financial inclusion.

Conclusion

The regulatory frame is going for a complete overhaul. While the new regulatory framework should have been expected to to smaller NBFCs out of regulatory glare, it is notable that only 76 companies are sliding down from SI status to NSI status due to the proposed change. The whole principle of scalar regulation should have been lesser entities to regulate, so that there is more attention where attention is needed. Further, the principle of scalar regulation would intuitively have more regulation at higher levels, but lesser regulation at the bottom of the pyramid. There are no apparent signals of reduced regulation at the base level. On an overall assessment, the scalar regulatory frame is a new thought process, and should be appreciated.

The video on “Round table discussion on RBI’s proposed regulatory framework for NBFCs” can be viewed here

Our Presentation on the topic can be viewed here

[1] See an article by Vinod Kothari, tilted Shadow Banking in India – Creating an Opportunity out of a Crisis, at http://vinodkothari.com/2020/01/shadow-banking-in-india/

[2] The 2020 Report is here: https://www.fsb.org/wp-content/uploads/P161220.pdf

[3] https://www.rbi.org.in/Scripts/BS_PressReleaseDisplay.aspx?prid=50748

[4] https://rbidocs.rbi.org.in/rdocs/Publications/PDFs/DP220121630D1F9A2A51415B98D92B8CF4A54185.PDF

Digital Consumer Lending: Need for prudential measures and addressing consumer protection

/0 Comments/in Banking Regulations, Consumer Protection, Financial Services, Fintech, Fintechs and Payment and Settlement Systems, NBFCs, RBI /by Vinod Kothari Consultants-Siddarth Goel (finserv@vinodkothari.com)

Introduction

“If it looks like a duck, swims like a duck, and quacks like a duck, then it probably is a duck”

The above phrase is the popular duck test which implies abductive reasoning to identify an unknown subject by observing its habitual characteristics. The idea of using this duck test phraseology is to determine the role and function performed by the digital lending platforms in consumer credit.

Recently the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) has constituted a working group to study how to make access to financial products and services more fair, efficient, and inclusive.[1] With many news instances lately surrounding the series of unfortunate events on charging of usurious interest rate by certain online lenders and misery surrounding the threats and public shaming of some of the borrowers by these lenders. The RBI issued a caution statement through its press release dated December 23, 2020, against unauthorised digital lending platforms/mobile applications. The RBI reiterated that the legitimate public lending activities can be undertaken by Banks, Non-Banking Financial Companies (NBFCs) registered with RBI, and other entities who are regulated by the State Governments under statutory provisions, such as the money lending acts of the concerned states. The circular further mandates disclosure of banks/NBFCs upfront by the digital lender to customers upfront.

There is no denying the fact that these digital lending platforms have benefits over traditional banks in form of lower transaction costs and credit integration of the unbanked or people not having any recourse to traditional bank lending. Further, there are some self-regulatory initiatives from the digital lending industry itself.[2] However, there is a regulatory tradeoff in the lender’s interest and over-regulation to protect consumers when dealing with large digital lending service providers. A recent judgment by the Bombay High Court ruled that:

“The demand of outstanding loan amount from the person who was in default in payment of loan amount, during the course of employment as a duty, at any stretch of imagination cannot be said to be any intention to aid or to instigate or to abet the deceased to commit the suicide,”[3]

This pronouncement of the court is not under criticism here and is right in its all sense given the facts of the case being dealt with. The fact there needs to be a recovery process in place and fair terms to be followed by banks/NBFCs and especially by the digital lending platforms while dealing with customers. There is a need to achieve a middle ground on prudential regulation of these digital lending platforms and addressing consumer protection issues emanating from such online lending. The regulator’s job is not only to oversee the prudential regulation of the financial products and services being offered to the consumers but has to protect the interest of customers attached to such products and services. It is argued through this paper that there is a need to put in place a better governing system for digital lending platforms to address the systemic as well as consumer protection concerns. Therefore, the onus of consumer protection is on the regulator (RBI) since the current legislative framework or guidelines do not provide adequate consumer protection, especially in digital consumer credit lending.

Global Regulatory Approaches

US

The Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) has laid a Special Purpose National Bank (SPNV) charters for fintech companies.[4] The OCC charter begins reviewing applications, whereby SPNV are held to the same rigorous standards of safety and soundness, fair access, and fair treatment of customers that apply to all national banks and federal savings associations.

The SPNV that engages in federal consumer financial law, i.e. in provides ‘financial products and services to the consumer’ is regulated by the ‘Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB)’. The other factors involved in application assessment are business plans that should articulate a clear path and timeline to profitability. While the applicant should have adequate capital and liquidity to support the projected volume. Other relevant considerations considered by OCC are organizers and management with appropriate skills and experience.

The key element of a business plan is the proposed applicant’s risk management framework i.e. the ability of the applicant to identify, measure, monitor, and control risks. The business plan should also describe the bank’s proposed internal system of controls to monitor and mitigate risk, including management information systems. There is a need to provide a risk assessment with the business plan. A realistic understanding of risk and there should be management’s assessment of all risks inherent in the proposed business model needs to be shown.

The charter guides that the ongoing capital levels of the applicant should commensurate with risk and complexity as proposed in the activity. There is minimum leverage that an SPNV can undertake and regulatory capital is required for measuring capital levels relative to the applicant’s assets and off-balance sheet exposures.

The scope and purpose of CFPB are very broad and covers:

“scope of coverage” set forth in subsection (a) includes specified activities (e.g., offering or providing: origination, brokerage, or servicing of consumer mortgage loans; payday loans; or private education loans) as well as a means for the CFPB to expand the coverage through specified actions (e.g., a rulemaking to designate “larger market participants”).[5]

CFPB is established through the enactment of Dood-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act. The primary function of CFPB is to enforce consumer protection laws and supervise regulated entities that provide consumer financial products and services.

“(5)CONSUMER FINANCIAL PRODUCT OR SERVICES The term “consumer financial product or service” means any financial product or service that is described in one or more categories under—paragraph (15) and is offered or provided for use by consumers primarily for personal, family, or household purposes; or **

“(15)Financial product or service-

(A)In general The term “financial product or service” means—(i)extending credit and servicing loans, including acquiring, purchasing, selling, brokering, or other extensions of credit (other than solely extending commercial credit to a person who originates consumer credit transactions);”

Thus CFPB is well placed as a separate institution to protect consumer interest and covers a wide range of financial products and services including extending credit, servicing, selling, brokering, and others. The regulatory environment has been put in place by the OCC to check the viability of fintech business models and there are adequate consumer protection laws.

EU

EU’s technologically neutral regulatory and supervisory systems intend to capture not only traditional financial services but also innovative business models. The current dealing with the credit agreements is EU directive 2008/48/EC of on credit agreements for consumers (Consumer Credit Directive – ‘Directive’). While the process of harmonising the legislative framework is under process as the report of the commission to the EU parliament raised some serious concerns.[6] The commission report identified that the directive has been partially effective in ensuring high standards of consumer protection. Despite the directive focussing on disclosure of annual percentage rate of charge to the customers, early payment, and credit databases. The report cited that the primary reason for the directive being impractical is because of the exclusion of the consumer credit market from the scope of the directive.

The report recognised the increase and future of consumer credit through digitisation. Further the rigid prescriptions of formats for information disclosure which is viable in pre-contractual stages, i.e. where a contract is to be subsequently entered in a paper format. There is no consumer benefit in an increasingly digital environment, especially in situations where consumers prefer a fast and smooth credit-granting process. The report highlighted the need to review certain provisions of the directive, particularly on the scope and the credit-granting process (including the pre-contractual information and creditworthiness assessment).

China

China has one of the biggest markets for online mico-lending business. The unique partnership of banks and online lending platforms using innovative technologies has been the prime reason for the surge in the market. However, recently the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) and China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission (CBIRC) issued draft rules to regulate online mico-lending business. Under the draft rules, there is a requirement for online underwriting consumer loans fintech platform to have a minimum fund contribution of at least 30 % in a loan originated for banks. Further mico-lenders sourcing customer data from e-commerce have to share information with the central bank.

Australia

The main legislation that governs the consumer credit industry is the National Consumer Credit Protection Act (“National Credit Act”) and the National Credit Code. Australian Securities & Investments Commission (ASIC) is Australia’s integrated authority for corporate, markets, financial services, and consumer credit regulator. ASIC is a consumer credit regulator that administers the National Credit Act and regulates businesses engaging in consumer credit activities including banks, credit unions, finance companies, along with others. The ASIC has issued guidelines to obtain licensing for credit activities such as money lenders and financial intermediaries.[7] Credit licensing is needed for three sorts of entities.

- engage in credit activities as a credit provider or lessor

- engage in credit activities other than as a credit provider or lessor (e.g. as a credit representative or broker)

- engage in all credit activities

The applicants of credit licensing are obligated to have adequate financial resources and have to ensure compliance with other supervisory arrangements to engage in credit activates.

UK

Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) is the regulator for consumer credit firms in the UK. The primary objective of FCA ensues; a secure and appropriate degree of protection for consumers, protect and enhance the integrity of the UK financial system, promote effective competition in the interest of consumers.[8] The consumer credit firms have to obtain authorisation from FCA before carrying on consumer credit activities. The consumer credit activities include a plethora of credit functions including entering into a credit agreement as a lender, credit broking, debt adjusting, debt collection, debt counselling, credit information companies, debt administration, providing credit references, and others. FCA has been successful in laying down detailed rules for the price cap on high-cost short-term credit.[9] The price total cost cap on high-cost short-term credit (HCSTC loans) including payday loans, the borrowers must never have to pay more in fees and interest than 100% of what they borrowed. Further, there are rules on credit broking that provides brokers from charging fees to customers or requesting payment details unless authorised by FCA.[10] The fee charged from customers is to be reported quarterly and all brokers (including online credit broking) need to make clear that they are advertising as a credit broker and not a lender. There are no fixed capital requirements for the credit firms, however, adequate financial resources need to be maintained and there is a need to have a business plan all the time for authorisation purposes.

Digital lending models and concerns in India

Countries across the globe have taken different approaches to regulate consumer lending and digital lending platforms. They have addressed prudential regulation concerns of these credit institutions along with consumer protection being the top priority under their respective framework and legislations. However, these lending platforms need to be looked at through the current governing regulatory framework from an Indian perspective.

The typical credit intermediation could be performed by way of; peer to peer (P2P) lending model, notary model (bank-based) guaranteed return model, balance sheet model, and others. P2P lending platforms are heavily regulated and hence are not of primary concern herein. Online digital lending platforms engaged in consumer lending are of significance as they affect investor’s and borrowers’ interests and series of legal complexions arise owing to their agency lending models.[11] Therefore careful anatomy of these models is important for investors and consumer protection in India.

Should digital lending be regulated?

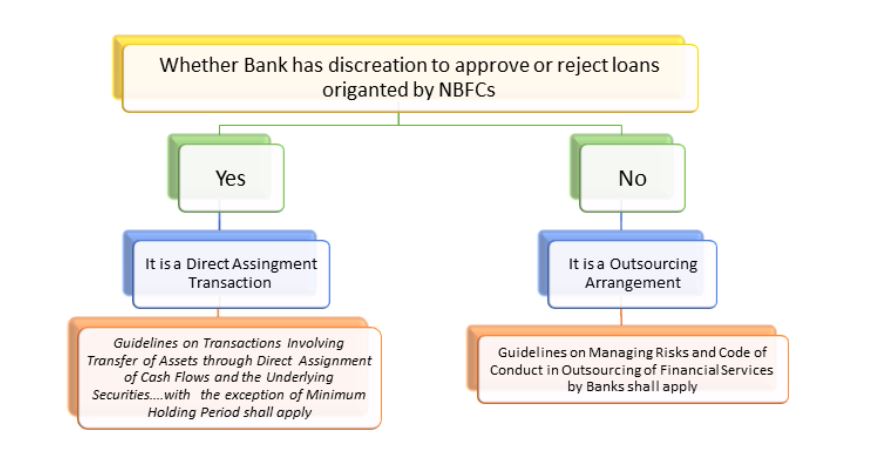

Under the current system, only banks, NBFCs, and money lenders can undertake lending activities. The regulated banks and NBFCs also undertake online consumer lending either through their website/platforms or through third-party lending platforms. These unregulated third-party digital lending platforms count on their sophisticated credit underwriting analytics software and engage in consumer lending services. Under the simplest version of the bank-based lending model, the fintech lending platform offers loan matching services but the loan is originated in books of a partnering bank or NBFC. Thus the platform serves as an agent that brings lenders (Financial institutions) and borrowers (customers) together. Therefore RBI has mandated fintech platforms has to abide by certain roles and responsibilities of Direct Selling Agent (DSA) as under Fair Practice Code ‘FPC’ and partner banks/NBFCs have to ensure Guidelines on Managing Risks and Code of Conduct in Outsourcing of Financial Service (‘outsourcing code’).[12] In the simplest of bank-based models, the banks bear the credit risk of the borrowers and the platform earns their revenues by way of fees and service charges on the transaction. Since banks and NBFCs are prudentially regulated and have to comply with Basel capital norms, there are not real systemic concerns.

However, the situation alters materially when such a third-party lending platform adopts balance sheet lending or guaranteed return models. In the former, the servicer platform retains part of the credit risk on its book and could also give some sort of loss support in form of a guarantee to its originating partner NBFC or bank.[13] While in the latter case it a pure guarantee where the third-party lending platform contractually promises returns on funds lent through their platforms. There is a devil in detailed scrutiny of these business models. We have earlier highlighted the regulatory issues in detail around fintech practices and app-based lending in our write up titled ‘Lender’s piggybacking: NBFCs lending on Fintech platforms’ gurantees’.

From the prudential regulation perspective in hindsight, banks, and NBFCs originating through these third-party lending platforms are not aware of the overall exposure of the platforms to the banking system. Hence there is a presence of counterparty default risk of the platform itself from the perspective of originating banks and NBFCs. In a real sense, there is a kind of tri-party arrangement where funds flow from ‘originator’ (regulated bank/NBFC) to the ‘platform’ (digital service provider) and ultimately to the ‘borrower'(Customer). The unregulated platform assumes the credit risk of the borrower, and the originating bank (or NBFC) assumes the risk of the unregulated lending platform.

Curbing unregulated lending

In the balance sheet and guaranteed return models, an undercapitalized entity takes credit risk. In the balance sheet model, the lending platform is directly taking the credit risk and may or may not have to get itself registered as NBFC with RBI. The registration requirement as an NBFC emanates if the financial assets and financial income of the platform is more than 50 % of its total asset and income of such business (‘principal business criteria’ see footnote 12). While in the guaranteed return model there is a form of synthetic lending and there is absolutely no legal requirement for the lending platform to get themselves registered as NBFC. The online lending platform in the guaranteed return model serves as a loan facilitator from origination to credit absorption. There is a regulatory arbitrage in this activity. Since technically this activity is not covered under the “financial activity” and the spread earned in not “financial income” therefore there is no requirement for these entities to get registered as NBFCs.[14]

Any sort of guarantee or loss support provided by the third-party lending platform to its partner bank/NBFC is a synthetic exposure. In synthetic lending, the digital lending platform is taking a risk on the underlying borrower without actually taking direct credit risk. Additionally, there are financial reporting issues and conflict of interest or misalignment of incentives, i.e. the entities do not have to abide by IND AS and can show these guarantees as contingent liabilities. On the contrary, they charge heavy interest rates from customers to earn a higher spread. Hence synthetic lending provides all the incentives for these third-party lending platforms to enter into risky lending which leads to the generation of sub-prime assets. The originating banks and NBFCs have to abide by minimum capital requirements and other regulatory norms. Hence the sub-prime generation of consumer credit loans is supplemented by heavy returns offered to the banks. It is argued that the guaranteed returns function as a Credit Default Swap ‘CDS’ which is not regulated as CDS. Thus the online lending platform escapes the regulatory purview and it is shown in the latter part this leads to poor credit discipline in consumer lending and consumer protection is often put on the back burner.

From the prudential regulation perspective restricting banks/NBFCs from undertaking any sort of guaranteed return or loss support protection, can curb the underlying emergence of systemic risk from counterparty default. While a legal stipulation to the effect that NBFCs/Banks lending through the third-party unregulated platform, to strictly lend independently i.e. on a non-risk sharing basis of the credit risk. Counterintuitively, the unregulated online lending platforms have to seek registration as an NBFC if they want to have direct exposure to the underlying borrower, subject to fulfillment of ‘principal business criteria’.[15] Such a governing framework will reduce the incentives for banks and NBFCs to exploit excessive risk-taking through this regulatory arbitrage opportunity.

Ensuring Fairness and Consumer Protection

There are serious concerns of fair dealing and consumer protection aspects that have arisen lately from digital online lending platforms. The loans outsourced by Banks and NBFCs over digital lending platforms have to adhere to the FPC and Outsourcing code.

The fairness in a loan transaction calls for transparent disclosure to the borrower all information about fees/charges payable for processing the loan application, disbursed, pre-payment options and charges, the penalty for delayed repayments, and such other information at the time of disbursal of the loan. Such information should also be displayed on the website of the banks for all categories of loan products. It may be mentioned that levying such charges subsequently without disclosing the same to the borrower is an unfair practice.[16]

Such a legal requirement gives rise to the age-old question of consumer law, yet the most debatable aspect. That mere disclosure to the borrower of the loan terms in an agreement even though the customer did not understand the underlying obligations is a fair contract (?) It is argued that let alone the disclosures of obligations in digital lending transactions, customers are not even aware of their remedies. Under the current RBI regulatory framework, they have the remedy to approach grievance redressal authorities of the originating bank/NBFC or may approach the banking ombudsman. However, things become even more peculiar in cases where loans are being sourced or processed through third-party digital platforms. The customers in the majority of the cases are unaware of the fact that the ultimate originator of the loan is a bank/NBFC. The only remedy for such a customer is to seek refuge under the Consumer Protection Act 2019 by way of proving the loan agreement is the one as ‘unfair contract’.

“2(46) “unfair contract” means a contract between a manufacturer or trader or service provider on one hand, and a consumer on the other, having such terms which cause significant change in the rights of such consumer, including the following, namely:— (i) requiring manifestly excessive security deposits to be given by a consumer for the performance of contractual obligations; or (ii) imposing any penalty on the consumer, for the breach of contract thereof which is wholly disproportionate to the loss occurred due to such breach to the other party to the contract; or (iii) refusing to accept early repayment of debts on payment of applicable penalty; or (iv) entitling a party to the contract to terminate such contract unilaterally, without reasonable cause; or (v) permitting or has the effect of permitting one party to assign the contract to the detriment of the other party who is a consumer, without his consent; or (vi) imposing on the consumer any unreasonable charge, obligation or condition which puts such consumer to disadvantage;”

It is pertinent to note that neither the scope of consumer financial agreements is regulated in India, nor are the third-party digital lending platforms required to obtain authorisation from RBI. There are instances of high-interest rates and exorbitant fees charged by the online consumer lending platforms which are unfair and detrimental to customers’ interests. The current legislative framework provides that the NBFCs shall furnish a copy of the loan agreement as understood by the borrower along with a copy of each of all enclosures quoted in the loan agreement to all the borrowers at the time of sanction/disbursement of loans.[17] However, like the persisting problem in the EU 2008/48/EC directive, even FPC is not well placed to govern digital lending agreements and disclosures. Taking a queue from the problems recognised by the EU parliamentary committee report. There is no consumer benefit in an increasingly digital environment, especially in situations where there are fast and smooth credit-granting processes. The pre-contractual information on the disclosure of annualised interest rate and capping of the total cost to a customer in consumer credit loans is central to consumer protection.

The UK legislation has been pro-active in addressing the underlying unfair contractual concerns, by fixation of maximum daily interest rates and maximum default fees with an overall cost cap of 100% that could be charged in short-term high-interest rates loan agreements. It is argued that in this Laissez-faire world the financial services business models which are based on imposing an unreasonable charge, obligations that could put consumers to disadvantage should anyways be curbed. Therefore a legal certainty in this regard would save vulnerable customers to seek the consumer court’s remedy in case of usurious and unfair lending.

The master circular on loan and advances provide for disclosure of the details of recovery agency firms/companies to the borrower by the originating bank/NBFC.[18] Further, there is a requirement for such recovery agent to disclose to the borrower about the antecedents of the bank/NBFC they are recovering for. However, this condition is barely even followed or adhered to and the vulnerable consumers are exposed to all sorts of threats and forceful tactics. As one could appreciate in jurisdictions of the US, UK, Australia discussed above, consumer lending and ancillary services are under the purview of concerned regulators. From the customer protection perspective, at least some sort of authorization or registration requirement with the RBI to keep the check and balances system in place is important for consumer protection. The loan recovery business is sensitive hence there is a need for a proper guiding framework and/or registration requirement of the agents acting as recovery agents on behalf of banks/NBFCs. The mere registration requirement and revocation of same in case of unprofessional activities will serve as a stick to check their consumer dealing practices.

The financial services intermediaries (other than Banks/NBFCs) providing services like credit broking, debt adjusting, debt collection, debt counselling, credit information, debt administration, credit referencing to be licensed by the regulator. The banks/NBFCs dealing with the licensed market intermediaries would go much farther in the successful implementation of FPC and addressing consumer protection concerns from the current system.

Conclusion

From the perspective of sound financial markets and fair consumer practices, it is always prudent to allow only those entities in credit lending businesses that are best placed to bear the credit risk and losses emanating from them. Thus, there is a dearth of a comprehensive legislative framework in consumer lending from origination to debt collection and its administration including the business of providing credit references through digital lending platforms. There may not be a material foreseeable requirement for regulating digital lending platforms completely. However, there is a need to curb synthetic lending by third-party digital lending platforms. Since a risk-taking entity without adequate capitalization will tend to get into generating risky assets with high returns. The off-balance sheet guarantee commitments of these entities force them to be aggressive towards their customers to sustain their businesses. This write-up has explored various regulatory approaches, where jurisdictions like the US and UK, and Australia being the good comparable in addressing consumer protection concerns emanating from online digital lending platforms. Henceforth, a well-framed consumer protection system especially in financial products and services would go much farther in the development and integration of credit through digital lending platforms in the economy.

[1] Reserve Bank of India – Press Releases (rbi.org.in), dated January 13, 2020

[2] Digital lending Association of India, Code of Conduct available at https://www.dlai.in/dlai-code-of-conduct/

[3] Rohit Nalawade Vs. State of Maharashtra High Court of Bombay Criminal Application (APL) NO. 1052 OF 2018 < https://images.assettype.com/barandbench/2021-01/cf03e52e-fedd-4a34-baf6-25dbb55dbf29/Rohit_Nalawade_v__State_of_Maharashtra___Anr.pdf>

[4] https://www.occ.gov/topics/supervision-and-examination/responsible-innovation/comments/pub-special-purpose-nat-bank-charters-fintech.pdf

[5] 12 USC 5514(a); Pay day loans are the short term, high interest bearing loans that are generally due on the consumer’s next payday after the loan is taken.

[6] EU, ‘Report from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council: on the implementation of Directive 2008/48/EC on credit agreement for consumers’, dated November, 05, 2020, available at < https://ec.europa.eu/transparency/regdoc/rep/1/2020/EN/COM-2020-963-F1-EN-MAIN-PART-1.PDF>

[7] https://asic.gov.au/for-finance-professionals/credit-licensees/applying-for-and-managing-your-credit-licence/faqs-getting-a-credit-licence/

[8] FCA guide to consumer credit firms, available at < https://www.fca.org.uk/publication/finalised-guidance/consumer-credit-being-regulated-guide.pdf>

[9] FCA, ‘Detailed rules for price cap on high-cost short-term credit’, available at < https://www.fca.org.uk/publication/policy/ps14-16.pdf>

[10] FCA, Credit Broking and fees, available at < https://www.fca.org.uk/publication/policy/ps14-18.pdf>

[11] Bank of International Settlements ‘FinTech Credit : Market structure, business models and financial stability implications’, 22 May 2017, FSB Report

[12] See our write up on ‘ Extension of FPC on lending through digital platforms’ , available at < http://vinodkothari.com/2020/06/extension-of-fpc-on-lending-through-digital-platforms/>

[13] Where the unregulated platform assumes the complete credit risk of the borrower there is no interlinkage with the partner bank and NBFC. The only issue that arises is from the registration requirement as NBFC which we have discussed in the next section. Also see our write up titled ‘Question of Definition: What Exactly is an NBFC’ available at http://vinodkothari.com/nbfcs/definition-of-nbfcs-concept-of-principality-of-business/

[14] The qualifying criteria to register as an NBFC has been discussed in our write up titled ‘Question of Definition: What Exactly is an NBFC’ available at http://vinodkothari.com/nbfcs/definition-of-nbfcs-concept-of-principality-of-business/

[15] see our write up titled ‘Question of Definition: What Exactly is an NBFC’ available at http://vinodkothari.com/nbfcs/definition-of-nbfcs-concept-of-principality-of-business/

[16] Para 2.5.2, RBI Guidelines on Fair Practices Code for Lender

[17] Para 29 of the guidelines on Fair Practices Code, Master Direction on systemically/non-systemically important NBFCs.

[18] Para 2.6, Master Circular on ‘Loans and Advances – Statutory and Other Restrictions’ dated July 01, 2015;

Our Other Related Write-Ups

Lenders’ piggybacking: NBFCs lending on Fintech platforms’ guarantees – Vinod Kothari Consultants

Extension of FPC on lending through digital platforms – Vinod Kothari Consultants

Fintech Framework: Regulatory responses to financial innovation – Vinod Kothari Consultants

One-stop guide for all Regulatory Sandbox Frameworks – Vinod Kothari Consultants

CKYCR becomes fully operational: The long-awaited format for legal entities’ information finally introduced

/3 Comments/in KYC/PMLA, NBFCs /by Vinod Kothari Consultants-Kanakprabha Jethani (kanak@vinodkothari.com)

Background

The Central KYC Registry (CKYCR) is a registry that serves as a central record for KYC information of all the customers of financial institutions. In India, the Central Registry of Securitisation Asset Reconstruction and Security Interest of India (CERSAI) has been authorised to carry out the functions of CKYCR. It was operationalised in 2016 beginning with collecting information on ‘individual’ accounts. Until now, the CKYCR did not have a feature to collect KYC information of legal entities.

The CERSAI has, in consultation with the RBI, prepared a template for submission of KYC information of legal entities (the same is yet to be published by CERSAI). The RBI has, through a notification dated December 18, 2020[1] (‘Notification’) directed financial institutions to begin submitting KYC information of legal entities w.e.f April1, 2021 (‘Notified Date’). The Master Direction – Know Your Customer (KYC) Direction, 2016 (‘KYC Directions’) have been updated in line with the said notification.

In this note we have discussed the implications for NBFCs, having customer interface, specifically.

Actionables for financial entities

In compliance with the existing KYC provisions on CKYCR and the Notification, NBFCs shall be required to take the following steps:

For customer who are legal entities, other than individuals and FPIs

- Ensure uploading KYC data of legal entities whose loan account has been opened after the Notified Date; within 10 days of commencement of an account-based relationship with the customer. It is to be noted that the existing time limit for uploading the documents of individual accounts was 3 days.

- Ensure uploading KYC records of legal entities on CKYCR, whose accounts are opened before the Notified Date, while undertaking periodic updation[2] or otherwise on receipt of updated KYC information from the customers. (When KYC information is uploaded during periodic updation or otherwise, it must be ensured that the same is in accordance with the CDD process as prevailing at such time.) Such uploading may not be required for loan accounts that are closed before undertaking the first periodic updation after the Notified Date.

- Communicate the KYC identifier generated after uploading of KYC information to the customer.

For individuals

- Ensure that the existing KYC records of individual customers pertaining to loan accounts opened prior to April 01, 2017, should be incrementally uploaded on CKYCR at the time of periodic updation or earlier when the updated KYC information is obtained/received from the customers. (When KYC information is uploaded during periodic updation or otherwise, it must be ensured that the same is in accordance with the CDD process as prevailing at such time.) Such uploading may not be required for loan accounts that are closed before undertaking the first periodic updation after the Notified Date.

- Ensure uploading KYC data of individual loan account opened after the Notified Date; within 10 days of commencement of an account-based relationship with the customer.

- Communicate the KYC identifier generated after uploading of KYC information to the customer.

Clarification with respect to identity verification through CKYCR

There has been a confusion regarding validity of identity verification done by fetching KYC details from the CKYCR. While the provisions of the Prevention of Money Laundering Act, 2002 (PMLA) and rules thereunder as well as the operating guidelines clearly state that if the customer submits KYC identifier for identity and address verification, no other documents need to be obtained.

The KYC Directions have remained silent on the same for long. The Notification also clarified that-

“Where a customer, for the purpose of establishing an account based relationship, submits a KYC Identifier to a RE, with an explicit consent to download records from CKYCR, then such RE shall retrieve the KYC records online from CKYCR using the KYC Identifier and the customer shall not be required to submit the same KYC records or information or any other additional identification documents or details, unless –

- there is a change in the information of the customer as existing in the records of CKYCR;

- the current address of the customer is required to be verified;

- the RE considers it necessary in order to verify the identity or address of the customer, or to perform enhanced due diligence or to build an appropriate risk profile of the client.”

Hence, for the purpose of verification, what is necessary is the KYC Identifier and an explicit consent from the customer to download his/her KYC information from the CKYCR.

Conclusion

The template for uploading KYC information of legal entities on the CKYCR portal has been formulated and shall be live on CERSAI Platform shortly. Financial institutions shall be required to ensure uploading of KYC information of legal entities w.e.f. the Notified Date. Further, additional obligations have been placed on financial institutions in terms of uploading KYC documents for existing customers and intimation of KYC identifier to all customers. Clarification regarding the validity of KYC verification using data from CKYCR is a welcome move.

[1] https://www.rbi.org.in/Scripts/NotificationUser.aspx?Id=12008&Mode=0

[2] As per para 38 of the KYC Directions- Periodic updation shall be carried out at least once in every two years for high risk customers, once in every eight years for medium risk customers and once in every ten years for low risk customers as per the prescribed procedure.

Impact of restructuring on ECL computation

/0 Comments/in Financial Services, Housing finance, NBFCs, RBI /by Vinod Kothari Consultants-Aanchal Kaur Nagpal (aanchal@vinodkothari.com)

Introduction

The disruption throughout the globe due to the COVID-19 pandemic has hit the Indian economy as well significantly. The financial sector has experienced a massive blow due to the impact of the pandemic on the credit worthiness and repayment capacity of the overall general public. RBI has responded through various measures including allowing moratorium period, providing resolution framework for stressed accounts due to COVID-19 and numerous other measures.

The retail borrower segment of several banks and NBFCs has also been adversely affected by the disruption and hence, the lenders are contemplating ways to extend certain benefits to such borrowers them under the various circulars issued by the RBI and government. In this regard, restructuring or modification in terms of a loan is being done for economic or legal reasons, relating to the borrower’s financial difficulty. However, such restructuring may also have implications on the books of accounts, especially for IndAS compliant entities.

The following note discusses the meaning of ‘restructuring’ and it impact on the credit risk of the borrower.

Meaning of Restructuring

As per RBI norms on Restructuring of Advances by NBFC, A restructured account is one where the NBFC, for economic or legal reasons relating to the borrower’s financial difficulty, grants to the borrower concessions that the NBFC would not otherwise consider.

As per the Basel guidelines on prudential treatment of problem assets –definitions of nonperforming exposures and forbearance, definition of forbearance is as follows:

4.1. Identification of forbearance

- Forbearance occurs when:

- a counterparty is experiencing financial difficulty in meeting its financial commitments; and

- a bank grants a concession that it would not otherwise consider, irrespective of whether the concession is at the discretion of the bank and/or the counterparty. A concession is at the discretion of the counterparty (debtor) when the initial contract allows the counterparty (debtor) to change the terms of the contract in their favour (embedded forbearance clauses) due to financial difficulty.

The meaning of restructuring is modification in terms of a loan, which is done for economic or legal reasons, relating to the borrower’s financial difficulty. Usually, restructuring may be of various types. A credit weakness related restructuring is one which is done to assist the borrower to continue to service the facility. If such restructuring was not done, potentially, the borrower may not have been able to service the facility. Therefore, this is done with a view to avert a default. Yet another type of restructuring is a preponement of payments or early clearance of a loan. A third example has been given in the definition itself – for example, passing on the benefit of any interest rate increase or decrease in case of floating rate loans.

Change in credit risk

Under Indian Accounting Standard (Ind AS) 109 Financial Instruments (‘IndAS 109’), Expected Credit Loss (ECL) provision is computed for the loan accounts and it is important to determine whether restructuring should be considered as a factor in determining change in the credit risk characteristic of the borrower.

Significant Increase in Credit Risk (SICR), in the context of IFRS 9, is a significant change in the estimated Default Risk (over the remaining expected life of the financial instrument). The term ‘significant’ is not defined in IFRS-9 and thus SICR is determined using various internal and external indicators. The provisions of para 5.5.12 of IndAS 109[1] are self-explanatory on the point that if there has been a modification of the contractual terms of a loan, then, in order to see whether there has been a SICR, the entity shall compare the credit risk before the modification, and the credit risk after the modification.

While SICR indicators usually suffice during normal circumstances, but adjusting to the ‘new normal’ would require ‘new’ ways to consider SICR. The most important question that arises is whether modification in the loan terms to avoid a credit default due to COVID-19 disruption would lead to SICR.

International Guidance

- As per the International Monetary Fund Report on The Treatment of Restructured Loans for FSI Compilation,

The BCBS (2017) defines loan forbearance as a situation in which (1) a counterparty is experiencing financial difficulty in meeting its financial commitments, and (2) a bank grants a concession that it would not otherwise consider, whether or not the concession is at the discretion of the bank and/or the counterparty. The Guide defines restructured loans as loans arising from rescheduling and refinancing of the original loan. Therefore, all forbearance measures are loan restructuring, but not all loan restructurings are forbearance measures.

Recently, in response to COVID-19 shock, the BCBS (2020) has clarified that when borrowers accept the terms of a payment moratorium (public or granted by banks on a voluntary basis) or have access to other relief measures such as public guarantees, these developments may not automatically lead to the loan being categorized as forborne. At the same time, banks would still need to assess the likelihood of the borrower’s rescheduled payments after the moratorium period ends.

- The Indian Accounting Standard Board also released a clarification under ‘IFRS 9 and Covid-19’[2] stating that,

Entities should not continue to apply their existing ECL methodology mechanically. For example, the extension of payment holidays to all borrowers in particular classes of financial instruments should not automatically result in all those instruments being considered to have suffered an SICR.

- According to the European Banking Authority’s Final Report on ‘Guidelines on reporting and disclosure of exposures subject to measures applied in response to the COVID‐19 crisis’[3],

More precisely, moratoria on loan payments that are in accordance with the EBA Guidelines on legislative and non‐legislative moratoria on loan repayments applied in the light of the COVID‐ 19 crisis do not trigger forbearance classification and the assessment of distressed structuring of loans and advances benefiting from these moratoria and they do not automatically lead to default classification. For example, if a performing loan is subject to a moratorium compliant with the GL on moratoria, which brings contractual changes to the terms of the loan, in the existing supervisory reporting this loan will continue to be reported under the category of performing exposures with no specific indication of the measures applied. However, it is also emphasised that the credit institutions should continue the monitoring and where necessary the unlikeliness to pay assessment of loans and advances that fall under the scope of these moratoria.

- The Prudential Regulatory Authority of the Bank of England sent letters[4] to CEOs of various Banks guiding the following –

Our expectation is that eligibility for, and use of, the UK Government’s policy on the extension of payment holidays should not automatically, other things being equal, result in the loans involved being moved into Stage 2 or Stage 3 for the purposes of calculating ECL or trigger a default under the EU Capital Requirements Regulation (CRR). This expectation extends to similar schemes to respond to the adverse economic impact of the virus.

We do not consider the use of a Covid-19 related payment holiday by a borrower to trigger the counting of days past due or generate arrears under CRR. We also do not consider the use of such a payment holiday to result automatically in the borrower being considered unlikely to pay under CRR.

Firms are reminded to apply sound risk management practices regarding the identification of defaults. Firms should continue to assess borrowers for other indicators of unlikeliness to pay, taking into consideration the underlying cause of any financial difficulty and whether it is likely to be temporary as a result of Covid-19 or longer term

Our expectation is that a covenant breach or waiver of a covenant relating to a modification of the audit report attached to audited financial statements because of the Covid-19 pandemic should not automatically, other things being equal, trigger a default under CRR or result in a move of the loans involved into Stage 2 or Stage 3 for the purposes of calculating ECL. This expectation extends to other covenant breaches and waivers of covenants with a direct link to the Covid-19 pandemic.

A breach of the covenants of a credit contract is a possible indication of unlikeliness to pay under the CRR definition of default. However, a covenant breach does not automatically trigger a default. Rather, firms have scope to assess covenant breaches on a case-by-case basis and determine whether they indicate unlikeliness to pay.

- The Accounting Standards Board of Canada[5] also took note of the guidance provided by IASB on guidance on applying IFRS 9 Financial Instrument. Further, it also took note of the guidance[6] provided by the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions (OFSI) in Canada and specified that the guidance is consistent with the requirements in IFRS 9 and should thus be considered along with the guidance provided by the IASB. The OFSI, through its guidance, provided the following in relation to applying IFRS in extraordinary circumstances –

IFRS 9 is principles-based and requires the use of experienced credit judgement. Consistent with OSFI’s IFRS 9 Financial Instruments and Disclosures guideline, OSFI is providing guidance on three specific aspects of the accounting for Expected Credit Losses (ECLs) due to the exceptional circumstances arising from COVID-19. Deposit taking Institutions (DTIs) should also consider any additional guidance provided by the International Accounting Standards Board on the application of IFRS 9 in relation to COVID-19.

Under the IFRS 9 ECL accounting framework, DTIs should consider both quantitative and qualitative information, including experienced credit judgment, in assessing for significant increase in credit risk. In OSFI’s view, the utilization of a payment deferral program should not result in an automatic trigger, all things being equal, for significant increase in credit risk.

- The International Public Sector Accounting Standards Board (IPSASB) released QnA[7] to provide insight into the financial reporting issues associated with COVID-19 government responses, and the relevant International Public Sector Accounting Standards (IPSAS). According to the same,

Given the economic severity associated with COVID-19, entities will need to review their portfolio of financial assets and assess whether an impairment is necessary.

Considering the aforesaid guidelines, all restructuring should not automatically be implied as SICR and the same should be based on facts after analyzing the background of credit worthiness of the borrower.

In case the restructuring is done under the disruption scenario then the same is not indicative of any increase in the probability of default. Accordingly, the same should ideally not be considered as a factor for considering SICR. Thus, if the restructuring is done for accounts that are stressed as a direct result of COVID-19, then the same shall not be treated as SICR.

However, if the restructuring is granted as a generalized option to all customers without any attention paid to reasons for such credit weakness, then the same is done to merely avoid credit difficulty or default of such borrowers which may not necessarily be caused by COVID-19.