Sikha Bansal, Partner (sikha@vinodkothari.com) and Payal Agarwal, Executive (payal@vinodkothari.com)

Introduction

ESG (where, E stands for Environment, S for Society, and G for Governance) is a term that has earned a lot of attention in the recent years. Related terms used are ESG investing, ESG reporting, ESG rating, etc. – all focussing on and circumscribing same factors.

The ESG analysis is sought as a measure of responsible investing, and goes beyond the traditional method of using only financial factors for evaluation of an investment or potential investment. ESG, in essence, recognises financial relevance of various non-financial elements which impact business in several ways. With sustainable development being the desirable result of whatever we do, efforts have been made to incorporate ESG issues in the analysis of the business performance as a whole.

In context of the same, we have tried identifying ESC concerns in India, in relation to corporate businesses. While in India, we have already something called ‘business responsibility reporting’, we need to see if this sufficiently captures the spirit of ESG and where it stands vis-à-vis global practices.

What is ESG?

Before we go on to the question why we need ESG, we need to understand what ESG, and also, why and how it has assumed so much of importance.

The emergence of ESG dates back to earlier years of 2000s. A report titled “Who Cares Wins: Connecting Financial Markets to a Changing World”[1], highlighted the emerging ESG issues and made several recommendations, including – (i) financial institutions should commit to integrating environmental, social, and governance factors in a more systematic way in research and investment processes, (ii) the companies a leadership role by implementing environmental, social and corporate governance principles and polices and to provide information and reports on related performance in a more consistent and standardised format, and (iii) investors shall explicitly request and reward research that includes environmental, social and governance aspects and to reward well-managed companies. Further, the report recommended that the financial analysts shall not only focus on ESG risks and risk management, but also consider ESG issues as a potential source of competitive advantage. The report also identified the following drivers through which good management of ESG issues can contribute to shareholder value creation[2].

Later, UNEP FI, in its 2005 Report[3], highlighted the distinction between ‘value-driven’ vs. ‘values-driven’ investment, and observes, “ESG considerations are capable of affecting investment decision-making in two distinct ways: they may affect the financial value to be ascribed to an investment as part of the decision-making process and they may be relevant to the objectives that investment decision-makers pursue.” This report noted that, the movement towards mainstream consideration of ESG issues in investment decision-making is a response of variety of factors, including, increasing evidence of the nexus between performance on ESG issues and financial performance, reputational concerns, consumer pressure, public opinion, introduction of corporate environmental reporting obligations, etc.[4]

Some institutional investors believed that environmental, social and governance (ESG) issues were not relevant to portfolio value, and were therefore not consistent with their fiduciary duties. However, in report titled “Fiduciary Duty in the 21st Century’[5], issued by UN agencies and PRI[6], it was clarified that the assumption is no longer supported, and that, failing to consider long-term investment value drivers, which include environmental, social and governance issues, in investment practice is a failure of fiduciary duty. The said report identifies critical importance of incorporating ESG standards into regulatory conceptions of fiduciary duty, for mainly three reasons – firstly, ESG incorporation is an investment norm; second, ESG issues are financially material; and thirdly, policy and regulatory frameworks are changing to require ESG incorporation.

Presently, there are several organisations, projects and reports focussing on ESG issues. These organisations may be governmental as well as independent. For instance, Global Reporting Initiative (GRI)[7] has formulated several standards[8] for sustainability reporting. See also, OECD (2017), Investment governance and the integration of environmental, social and governance factors.

Pillars of ESG

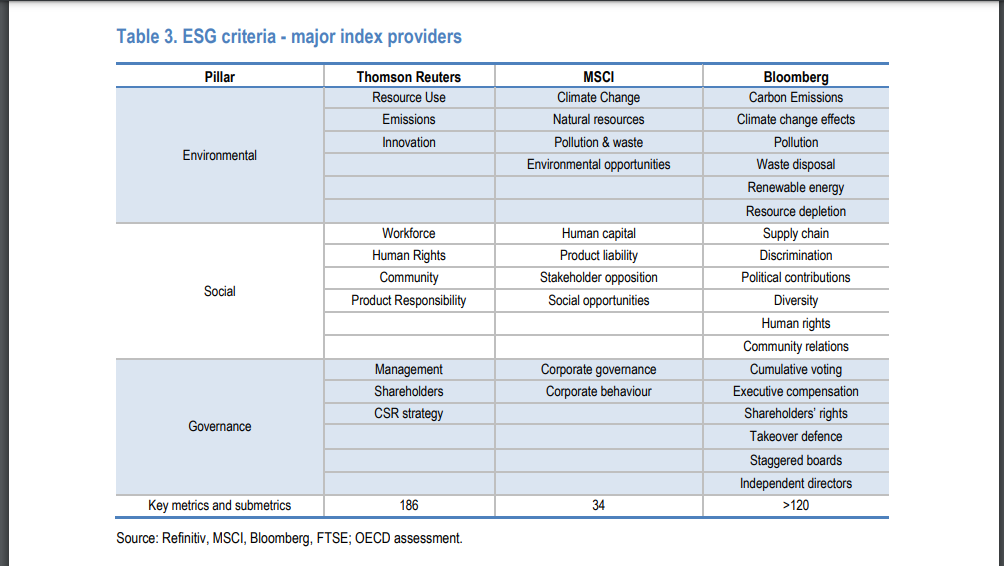

ESG, as stated above, has 3 pillars – Environmental, Social and Governance Each of these pillars comprises of several factors which would be a ‘parameter’ in ESG analysis.

- “environmental” pillar focusses on creating a sustainable environment, where parameters such as impact of a company’s activities on the climate, company’s liability towards the environment, creating eco-friendly products, etc are checked and measured;

- “social” aspect focusses on creating value for the society, by laying emphasis on the human rights issues, workplace health and safety, labour training and management, interaction with communities, customer relationship etc;

- “governance” aspect covers issues on the corporate governance of a company and has two main elements: corporate structures, and corporate behaviour.

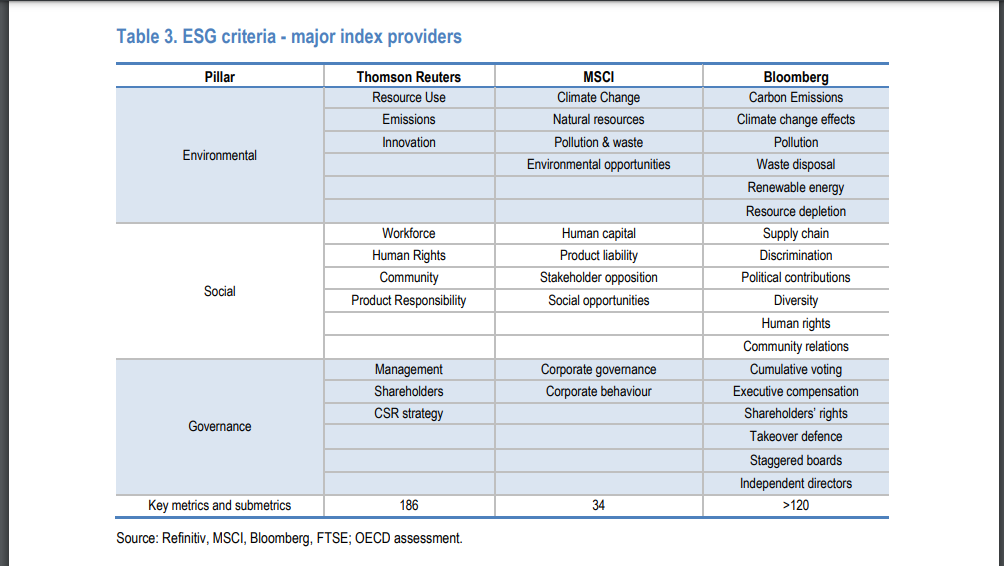

We have compiled a list of such factors[9] as below –

ESG Reporting

EU law requires large companies to disclose certain information on the way they operate and manage social and environmental challenges. EU’s directive, 2014/95/EU also called the non-financial reporting directive (NFRD), acknowledges that disclosure of non-financial information is vital for managing change towards a sustainable global economy by combining long-term profitability with social justice and environmental protection and lays down the rules on disclosure of non-financial and diversity information by large companies[10]. The Directive amends the accounting directive 2013/34/EU (by inserting Article 19a) so as to mandate inclusion of non-financial statement containing information to the extent necessary for an understanding of the undertaking’s development, performance, position and impact of its activity, relating to, as a minimum, environmental, social and employee matters, respect for human rights, anti-corruption and bribery matters, etc.

It further provides, “Where the undertaking does not pursue policies in relation to one or more of those matters, the non-financial statement shall provide a clear and reasoned explanation for not doing so.”

The EU has issued its guidelines to help companies disclose environmental and social information, and published guidelines on reporting climate-related information. Also, EU has also launched a public consultation on the review of the NFRD[11].

The OECD Report of 2017[12] compiles ESG reporting requirements (voluntary as well as mandatory) across the world by institutional investors, and by way of corporate disclosures. The report observes that the reporting requirements are usually voluntary (“comply or explain”) and are not prescriptive on the methods or metrics to be used.

The Financial Reporting Council (FRC) of UK released a discussion paper – “A Matter of Principles: The Future of Corporate Reporting” (2020). The discussion paper proposes a network of interconnected reports based on objectives rather than a single comprehensive annual report. The proposals include 3 reports – Business report, the full Financial Statements and a new Public Interest Report. It also focuses on widening the definition of materiality so that it does not remain limited to accounting standards only, but covers other wider range of activities that affect a company significantly. Section 6 of the this Report deals extensively with non-financial reporting, stated to include information relating to employees, suppliers, customers, the community, the environment and human rights.

In a study, “The consequences of mandatory corporate sustainability reporting: evidence from four countries (2015)”, it has been observed that even though the regulations often allowed companies, via comply or explain clauses, to choose not to make greater disclosure, there was a 30%-50% average increase in ESG disclosure as a result of the regulations being introduced (albeit from a low starting base). The greatest increase came in the first year of the regulations coming into force. All three types of disclosure – environmental, social and governance – increased. The findings, therefore, suggest that, contrary to popular belief that an increase in disclosure regulation imposes significant costs on companies and, therefore, has a negative impact on shareholders, the reality is that improved disclosure creates value for companies, not destroys it.

ESG Rating

Investors, institutional institutions, etc. would generally make use of ESG information for investment decisions through ESG ratings provided by ESG rating agencies[13]. This assessment and measurement often forms the basis of informal and shareholder proposal-related investor engagement with companies on ESG matters[14]. ESG factors can provide valuable insights into possible current and future environmental and social risks and opportunities for corporate entities, given the impact and dependence entities have on the environment and society. These ESG issues in turn have the potential to lead to a direct or indirect financial impact on the entity’s profits and investment returns[15].

See Boffo, R., and R. Patalano (2020), “ESG Investing: Practices, Progress and Challenges”, OECD Paris, for an elaborate discussion on ESG rating and indices and the methodologies adopted for the same. The paper also compiles ESG Criteria as used by major index providers as follows[16] –

Even though there are countries where ESG Reporting has been initiated as a voluntary or mandatory measure, the requirement of ESG rating has not been found to be mandated in any country by way of explicit regulations on the same. However, institutional investors, proxy advisor firms etc., are largely using these ratings while making investment decisions as part of making socially responsible investment.

ESG in Indian Context

The Indian legislation has been trying to cover the various aspects of ESG in a fragmented manner.

For instance, the board’s report shall disclose the conservation of energy, technology absorption, etc.[17] The aspects have to be dealt with in detail – the company shall disclose steps taken or impact on conservation of energy, steps taken to utilise alternate sources of energy, capital investment in energy conservation equipments, efforts towards technology absorption, etc. Besides, a director owes a fiduciary duty towards the community as well as for the protection of the environment[18]. Also, CSR activities include various socio-economic activities, required to be disclosed separately in the annual report[19]. However, the closest requirement is that of Business responsibility Reports (BRR) which has been mandated from ESG perspective only, as discussed below.

What is Business Responsibility Report (BRR)?

BRR or Business Responsibility Report can be said to be the foremost step in India in promoting non-financial reporting in India, on a mandatory basis. The initiative was one of the responses to India’s commitment towards the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business & Human Rights (UNGPs) and Sustainable Development Goals.

The BRR is based on the 9 principles in line with the ‘National Voluntary Guidelines on Social, Environmental and Economic Responsibilities of Business’ (NVG)[20] issued by MCA. The guidelines state that the companies should not be just responsible but also socially, economically and environmentally responsible. Through such reporting, the guidelines expect that businesses will also develop a better understanding of the process of transformation that makes their operations more responsible. The NVG were further revised and the MCA formulated the ‘National Guidelines on Responsible Business Conduct’ (NGRBC)[21]. The said guidelines stipulated that the businesses should –

- conduct and govern themselves with integrity in a manner that is Ethical, Transparent and Accountable,

- provide goods and services in a manner that is sustainable and safe,

- respect and promote the well-being of all employees, including those in their value chains,

- respect the interests of and be responsive to all their stakeholders,

- respect and promote human rights,

- respect and make efforts to protect and restore the environment,

- when engaging in influencing public and regulatory policy, should do so in a manner that is responsible and transparent,

- promote inclusive growth and equitable development, and

- engage with and provide value to their consumers in a responsible manner.

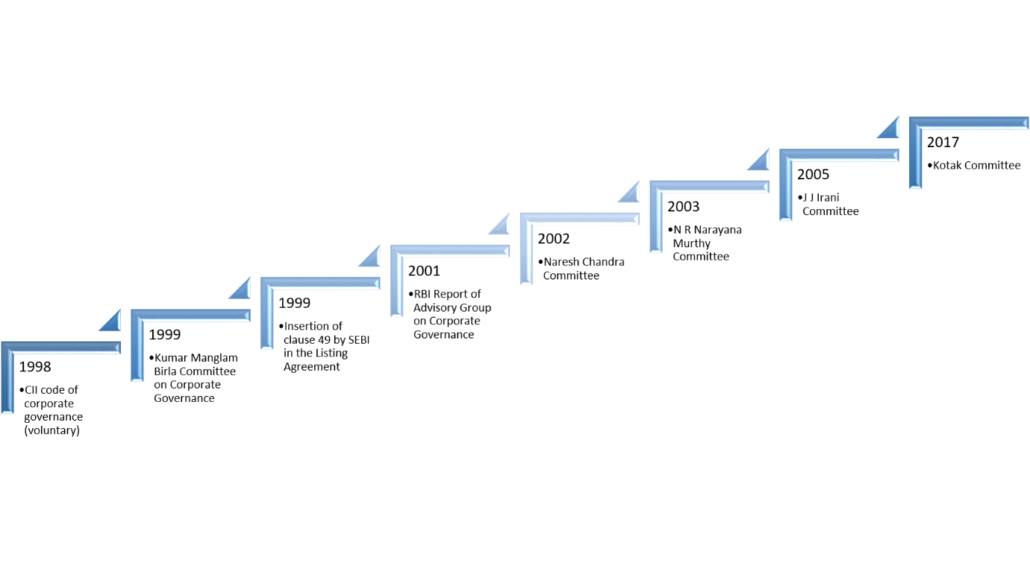

The Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI), in 2012[22], through its listing conditions mandated the top 100 listed entities by market capitalisation to file BRR from ESG perspective. This was extended to top 500 companies in FY 2015-16[23]. The coverage has been extended to 1000 companies now[24]. In the year 2020, MCA issued Report of the Committee on the Business Responsibility Reporting, and SEBI issued a Consultation Paper on the format for Business Responsibility and Sustainability Reporting (BRSR, suggesting that BRR shall be renamed as BRSR). See our detailed analysis of the recommendations made in these reports.

See also, our earlier article on BRR. The eventual development in BRR framework is shown below –

BRR – Identifying ways to improve

ESG has no statutory definition, per se. We have tried identifying possible factors, based on various reports, indices, etc. which would reflect a holistic ESG perspective of an entity.

How effective is the present framework of BRR can be understood by way of the following table:

BRR vs ESG – Hits and Misses

| Hits |

Misses |

| Climate change |

Carbon emissions |

| Resource use , sustainable sourcing |

Green building |

| Environmental protection and restoration |

Biodiversity and land use |

| Renewable energy |

Discharge of effluents |

| Water use |

————- |

| Energy efficiency |

————— |

| Clean tech |

—————- |

| Safety of employees, customers |

Privacy and data security |

| Skill upgradation training |

Financial product liability |

| Labour management |

———— |

| Practice against child labour, sexual harassment, forced labour |

———— |

| Protection of human rights |

————- |

| Satisfactory redressal of customer complaints |

———— |

| Stakeholder engagement |

———— |

| Ethics and bribery |

Board structure |

| Anti competitive behaviour |

Executive pay |

| Unfair trade practices |

Codes and values |

| —————– |

Tax transparency |

Most of these gaps in the present BRR format are covered under the proposed BRSR. The BRSR has provisions for reporting on the carbon emissions of a company, discharge of other effluents by the company, and reporting relating to the privacy and data security of the customers etc. Also, the BRSR defines the scope of reporting for every item very precisely.

However, matters such as financial product liability and various aspects of governance still needs a dedicated space.

NSE Study of BRR Reporting in India

A study of NSE, while conducting the ESG analysis of Indian companies, has checked the disclosures provided under the BRR framework by the companies as part of its ESG analysis.

Some significant findings of the study has been pointed below:

- Among the nine principles, the least number of sample companies responded positively for disclosures on principle 7 (i.e., public advocacy). It had the lowest score on all four measures.

- One of the recurring reasons for not framing a policy on the principle 7 is that there is no specific/ formal policy on public advocacy. However, companies have stated that they indirectly covered aspects of principle 7 under other policies. This may be attributed to the fact that in India, advocacy, if at all done, is done in a non-transparent manner.

- The second worst response was with respect to the principles relating to ‘respect and promoting human rights’ and ‘engagement and providing value to customers and consumers’. Once again, probably, these concepts are yet to be assimilated in our system.

- Higher positive responses were found across principle 1 (ethics), principle 3 (employees), principle 4 (stakeholder), principle 6 (environment), and principle 8 (growth and equitable development – social responsibility). This can be attributed to the fact that some of these policies flow from various legal mandates in India. Hence, most companies have formal policies to comply with the law on these principles.

The study highlights that companies have largely scored better on policy disclosures followed by governance factor, compared to environment and social factors. This can be attributed to the fact that governance reforms have transformed into laws by various regulatory agencies within India, in the last two decades. Similarly, many policies have been mandated to be prepared by regulatory authorities. Hence, companies have scored higher on policy disclosure parameters.

Closing Thoughts

The BRR Reporting in India, in terms of key areas, goes a long way in presenting a holistic ESG scenario. Some structural changes in the extant format may facilitate better reporting.

Further, the Indian companies are found to perform well in the governance related matters, in comparison to the environmental and social factors, admittedly for the presence of various statutory requirements and regulatory supervision on the governance requirements of a company. However, the companies need to improve their environmental and social scores as well.

[1] December, 2004. The Report was a joint initiative of financial institutions which were invited by United Nations Secretary-General Kofi Annan to develop guidelines and recommendations on how to better integrate environmental, social and corporate governance issues in asset management, securities brokerage services and associated research functions. See also, “Who Cares Wins” : One Year On” – A Review of the Integration of Environmental, Social and Governance Value Drivers in Asset Management, Financial Research and Investment Processes, published by the International Finance Corporation.

[2] Refer, page 12 exhibit 9 of the said Report

[3] A legal framework for the integration of environmental, social and governance issues into institutional investment”

[4] Refer, page 24 of the said Report.

[5] The website is https://www.fiduciaryduty21.org/ . The report has been last updated in the year 2019.

[6] Principles of Responsible Investing (PRI) is a United Nations-supported initiative, launched in 2006 by UNEP Finance Initiative and the UN Global Compact.It is a network of international investors working together to put the six Principles for Responsible Investment into practice. The PRI were devised by the investment community and reflect the view that environmental, social and governance (ESG) issues can affect the performance of investment portfolios and therefore must be given appropriate consideration by investors if they are to fulfill their fiduciary (or equivalent) duty. In implementing the Principles, signatories contribute to the development of a more sustainable global financial system.

[7] GRI was founded in Boston in 1997 following public outcry over the environmental damage of the Exxon Valdez oil spill. The aim was to create the first accountability mechanism to ensure companies adhere to responsible environmental conduct principles, which was then broadened to include social, economic and governance issues. The first version of what was then the GRI Guidelines (G1) published in 2000 – providing the first global framework for sustainability reporting. The following year, GRI was established as an independent, non-profit institution. In 2016, GRI transitioned from providing guidelines to setting the first global standards for sustainability reporting – the GRI Standards.

[8] The GRI standards can be accessed here https://www.globalreporting.org/standards/

[9] The list is a compilation of the various factors identified by various organisations and reports such as, PRI, MSCI Research, NSE-SES report on ESG analysis of 50 Indian companies, etc.

[10] EU rules on non-financial reporting only apply to large public-interest companies with more than 500 employees. This covers approximately 6,000 large companies and groups across the EU.

[11] See here.

[12] OECD (2017) Investment governance and integration of environmental, social and governance factors

[13] Some well- known ESG rating providers include: (a) Dow-Jones Sustainability Index, (b) S & P Global Ratings, (c) MSCI ESG Research etc.

[14] https://corpgov.law.harvard.edu/2017/07/27/

[15] S&P Global Ratings: Exploring Links To Corporate Financial Performance

[16] Source: Boffo, R., and R. Patalano (2020), “ESG Investing: Practices, Progress and Challenges”, OECD Paris

[17]Companies Act, 2013, section 134(3)(m), read with rule 8 of the Companies (Accounts) Rules, 2014

[18] Ibid, section 166.

[19] Ibid, section 135 read with Companies (Corporate Social Responsibility Policy) Rules, 2014.

[20] 2011. A refinement of earlier Corporate Social Responsibility Voluntary Guidelines 2009, released by the Ministry of Corporate Affairs in December 2009.

[21] 2019. See Press Release.

[22] CIR/CFD/DIL/8/2012 dated 13th August, 2012

[23] See update, and notification.

[24] See notification.