Anushka Vohra | Manager and Ajay Kumar K V | Manager (corplaw@vinodkothari.com)

Introduction

Boards are seen as power-centres of a corporate entity. Hence, it is commonly seen that corporate disputes are often invoked out of and revolve around a certain section of shareholders seeking to seize directorship positions favouring the counter-set of shareholders.

Directors may be deprived of their office either due to disqualification, or due to circumstances leading to vacation of office, or resignation, or removal.

While the law, that is, the Companies Act, 2013 (‘CA, 2013’) has provisions around removal of directors, shareholder actions have been challenged in light of different interpretations being accorded to the provisions of Section 169 of CA, 2013 (which is akin to section 284 of the Companies Act, 1956) i.e. removal of a director, subject to certain conditions. However, courts keep facing certain reiterative but rather intriguing questions like – Whether the provisions are ‘exhaustive’ when it comes to removing a director? Whether shareholders constitute an omnipotent authority to dislodge the directors? Whether the board acting in its authority can remove a director without going to shareholders? Whether the removal of directors can happen in adherence to any other power of removal – say directors, nominator, or the like.

As a general rule, it is well accepted that the appointing authority shall have the power to remove a director from such office. However, the right of removal is not limited to the shareholders alone.

In this article, the authors have made an analysis of the ways in which a director can be removed from such office and the process to be followed for such removal.

Balance of powers between shareholders and directors

The CA, 2013 clearly demarcates the rights and obligations of shareholders and directors. The general administration of a company vests with the directors; they are the agents of a company and have a fiduciary duty towards the shareholders and all other stakeholders. The shareholders are referred to as owners of a company as they have their stake involved in the company.

Even though shareholders are the owners of the company, one cannot refute the fact that board of directors have an integral role in the routine affairs of a company and to keep the company as a going concern. Of late, there have been concerns as to whether the shareholders’ power to remove a director is an exceptional power. Essentially, there are following ways a director may be removed: statutory power of removal, a power of removal as per articles, a power of removal arising from terms of appointment, or a power of removal arising from terms of nomination.

The shareholders have been given a power under section 169 of the Act, that they may remove a director by passing an ordinary resolution. This power is usually exercised by the shareholders in situations where a director is acting mala-fide and ultra-vires their authority. In any event, as we discuss below, the right of a shareholder to remove a director does not have to be explained by reasons.

Legislative history

The provisions relating to removal of a director first came into being after the Cohen Committee recommended the same. The Cohen Committee was formed to recommend amendments to the Companies Act, 1929 (regulating the UK Company Law), which eventually formed the basis of the UK Companies Act of 1948. Section 184 of the Companies Act, 1948 provided for removal of directors. The same provided for obtaining shareholders approval by way of ordinary resolution, requirement of special notice. Sub-section(6) of section 184 states that- ‘nothing in this section shall be taken as depriving a person removed thereunder of compensation or damages payable to him in respect of termination of his appointment as director or of any appointment terminating with that as director or as derogating from any power to remove a director which may exist apart from this section.’

The same was retained under the Companies Act, 1985 and subsequently under the Companies Act, 2006.

There are certain jurisdictions which have empowered even the board of directors, by statute, to remove directors. For example, the Companies Act 71 of 2008 introduced into South African law a provision that, for the first time that empowers the board of directors to remove a director from office. The relevant extract of the same is as under:

‘(3) If a company has more than two directors, and a shareholder or director has alleged that a director of the company— (a) has become— (i) ineligible or disqualified in terms of section 69, other than on the grounds contemplated in section 69(8)(a); or (ii) incapacitated to the extent that the director is unable to perform the functions of a director, and is unlikely to regain that capacity within a reasonable time; or (b) has neglected, or been derelict in the performance of, the functions of director, the board, other than the director concerned, must determine the matter by resolution, and may remove a director whom it has determined to be ineligible or disqualified, incapacitated, or negligent or derelict, as the case may be.’

The granting of powers to the board for removal of directors is also a move towards ensuring a balance of powers among the two.

Under the UK Company Law, section 168 contains the provisions relating to removal of directors whereby a company is duly empowered to do so, by ordinary resolution, prior to the expiration of a director’s term of office. S168, inter alia, states that “Nothing in this section shall be taken as … derogating from any power to remove a director which may exist apart from this section,”

The same has been applied in various judicial pronouncements. In the case of Bersel Manufacturing Co Ltd v Berry ([1968] UKHL J0508-2), an express stipulation in the articles that certain directors had the “power to terminate forthwith the directorship … by notice in writing”, was held to have been valid. Also, referring to the case of Nelson v. James Nelson and Sons, Ld.[1], the articles of association of the company in that case contained Article 84 which empowered the Board to exercise all the powers of the company subject to the limitations mentioned in the article, and Article 85 empowered the Board to appoint from time to time any one or more of their number to be managing director and with such powers and authorities, and for such period as they deem fit, and to revoke such appointment.

Provisions under the Act, 2013

As discussed above, section 169 of the Act contains provisions for removal of directors. Similar provisions were there under section 284 of the erstwhile Companies Act, 1956 (‘Erstwhile Act’). Such provisions require shareholders’ approval by way of ordinary resolution and the same is coupled with the stringent requirement of special notice. The removal of directors under section 169 can be summed as under:

- The company may remove a director through its shareholders, by ordinary resolution, other than one who has been appointed by the Tribunal under section 242 of the Act;

- Such removal should be done before the expiry of the period of office of the director sought to be removed;

- Special notice shall be given eligible shareholders;

- Circulation of the special notice;

- As a principle of natural justice, before removal, the concerned director should be given a reasonable opportunity of being heard. [refer below for detailed procedure]

S.169(8) – exhaustive method of removal?

Section 169 begins with the phrase “A company may, by Ordinary Resolution ………”. The use of the word ‘may’ under section 169 itself implies that the procedure for removal prescribed in Section 169 is not exhausted and there may be various other ways to remove a director.

It is also pertinent to note that section 169(8)(b) inter-alia states that –

(8) Nothing in this section shall be taken—

XXX

(b) as derogating from any power to remove a director under other provisions of this Act.

From above it could be interpreted that the company is not precluded from bringing any alternate method which could be carved out of the existing rigid statutory provision.

Rights under the AoA-

The Courts have been liberally interpreting the provision of section 169 to state that where the AoA bestows power on the board to remove directors, compliance with section 169 will not be required. We have referred to some judicial pronouncements hereunder:

In the case of Ravi Prakash Singh v Venus Sugar Limited[2], the Delhi High Court held that –

‘sub-section 7(b) of Section 284 lays down that nothing in the section shall be taken as derogating from any power to remove a director which may exist apart from this section. The section itself therefore contemplates removal of a director in addition to the provisions contained in the Section. Thus where the Articles of Association confer powers on the Board of Directors to remove the Managing Director or other directors, such power is not affected by the provisions of Section 284.’

( “Emphasis supplied”)

The scope of section 284 was also discussed in the case of A.K. Home Chaudhary v. National Textile Corporation[3] wherein the Allahabad High Court held that the powers of Board to remove a director is not barred by section 284-

‘the Petitioner was appointed a whole time director under Article 85(d) and his services have been terminated by the Board of Directors in exercise of their powers under Article 86(c). The Articles of Association do not place any fetter on the power of the Board of Directors to remove a director from service. The powers of the Board of Directors with regard to removal of Director remains unaffected by section 284 of the Companies Act. The impugned order of termination, therefore, is not violative of section 284 of the Companies Act. In the result, for the reasons stated above, we hold that the petitioner is not entitled to any relief.’

Contradicting judgements-

There have been contradicting views by the court in deciding who has the power to remove a director from the office wherein the provisions of section 284 were held to be comprehensive for the course of removal of a director. In the case of Hem Raj Singh v. Naraingarh Distillery Limited[4], the NCLAT held that-

‘It is stated that the removal was in complete contravention of section 284 of the old act as no specific notice was served upon the Appellant as per sub-clause 2 to 4 of section 284 of the old act.’

Distinction between s. 169 and s. 284

Akin to section 169, section 284 of the Erstwhile Act provided provisions relating to removal of directors. However, there is a change w.r.t. the alternate remedy which both sections provide. A comparative analysis of the same can be drawn as under:

| Act, 2013 |

Erstwhile Act |

| Section 169. Removal of Directors

XXX

(8) Nothing in this section shall be taken-

XXX

(b) as derogating from any power to remove a director under other provisions of this Act. |

Section 284. Removal of Directors

XXX

(7) Nothing in this section shall be taken-

XXX

(b) as derogating from any power to remove a director which may exist apart from this section. |

The words, ‘which may exist apart from this section’ have been replaced by the words, ‘under any provisions of the Act.’ Does this provision have to necessarily be a statutory provision? Does this confer that right to removal under AoA of a company would be violative of section 169?

We are of the view that it is not necessary that there be a statutory provision, any power flowing from the AoA will also suffice. Referring to our detailed deliberations on the background and intent of the provision of removal of directors, it is clear that section 169 cannot be read de-hors of the background of section 284.

Further, we also refer to section 6 and 9 of the CA, 2013 and the Erstwhile Act, respectively, which states that-

Save as otherwise expressly provided in this Act—

XXX

(b) any provision contained in the memorandum, articles, agreement or resolution shall, to the extent to which it is repugnant to the provisions of this Act, become or be void, as the case may be.

While it is a settled proposition that the AoA cannot override the Act, however since there is a carve out under section 169(8), which may not necessarily be a statutory carve out, we understand that AoA of a company can provide for the powers of board to remove directors.

Intriguing questions w.r.t. Removal of directors by the shareholders

The process of removal of directors by the shareholders has various facets, of which the requirement of special notice is crucial. A question that arises is whether the special notice has to be accompanied with reasons for removal. In the case of LIC v. Escorts Limited[5], it was held that-

‘It is not necessary to give reasons in an explanatory statement for removal of a director as desired by section 173(2). Reason behind this judgement given by the court was that the company is acting on the basis of a special notice given by the shareholder u/s 284 and it is not a resolution proposed by the company.’

Process of removal of different directors

Under the provisions of Act, 2013 there are different types of directors viz. Executive Director(EDs),Non-Executive Director(NEDs), nominee director, additional director. The Law has made provisions for appointment and removal of all types of directors and differences lie in the method of appointment, authority for removal, etc. Below we analyse briefly the process for removal of different types of directors.

- EDs and NEDs- The process of removal of EDs and NEDs primarily be the same i.e.by the shareholders under section 169 or by the board of directors under powers bestowed by the AoA. In case of EDs, the terms of engagement may also be relevant to see for their removal.

- Nominee directors- The nominee directors can either be appointed by i.) a financial institution or ii.) by way of shareholders agreement. In the case of i.) above- it is an established principle of law that anybody vested with the power of appointment is also vested with the power of removal. The financial institutions or investors, generally referred to as nominators, ensures its representation on the board of the borrower company for the purpose of safeguarding their interest thereof. In the case of ii.) above the same view is held. We can also refer to a judicial pronouncement in this regard, in the case of Farrel Futado v State Of Goa And Others[6] it was held that –

‘It is now a well-settled principle of law laid down by various decisions of the apex court, that the power of appointment includes the power of removal. The power of removal in the present case flows from the right of appointment by the Administrator under article 68(1) of the articles of association. Once this aspect is kept in mind, it is clear that the petitioner has not been removed by the board of directors under section 284 of the Companies Act. It is a re-call of the nomination by the Administrator under article 68(1) read with article 68(4) of the articles of association. As a nominee of the Government, the petitioner represented the largest shareholder in the company and the Government was entitled to revoke the said nomination/appointment as a matte of right which flowed from articles 68(1) and 68(4) with regard to non-rotational director appointed by the Administrator. Section 284 of the Companies Act deal with removal of directors by the company. It requires a company to pass an ordinary resolution to remove a director (not being a director appointed by the Central Government under section 408 of the Companies Act).’

XXX

‘The Government’s right to revoke the appointment under article 68(1) is not the same things as removal of a director by the company under section 284 of the Companies Act. The two operate in different spheres. If this dichotomy is kept in mind, it is clear that power to revoke the appointment made under article 68(1) flows from the power to appoint under article 68(1) and it has nothing to do with the removal of a director under section 284 of the Companies Act.’

3. Additional directors- The board of directors under the powers given by the AoA may appoint an additional director, and until their appointment is regularised by the shareholders at a general meeting, the board of directors can remove an additional director.

4. Managing Director- A managing director is appointed in a dual capacity, i.e. as a managerial personnel and as a director. As a managing director his terms of engagement are usually determined by way of a formal letter. Therefore, termination of the services of a managing director is within the powers of the board and section 169 shall not be referred to in this regard.

In the case of S. Varadarajan v. Venkateshwara Solvent Extraction (P) Ltd: : 1994 80 CompCas 693 Mad, (1992) IIMLJ 130[7], it was held that section 284 does not come in the way of removal of the managing director by the board. Similar decision was taken in the case of Major General Shanta Shamsher v. Kamani brothers: : AIR 1959 Bom 201, (1958) 60 BOMLR 1024, 1959 29 CompCas 501 Bom[8].

Whether special notice under section 115 requires compliance with section 111?

The special notice required under section 169 shall be given as per the provisions of section 115[9] wherein the eligibility criteria and the manner in which such notice of resolution shall be circulated to the members have been prescribed. However, the interesting question here is, whether such circulation to members shall be in compliance with section 111[10]?

The language of section 111 itself gives a direct connection with section 100[11] where it provides the eligibility criteria for giving a notice of resolution for circulation amongst the shareholders. It should also be noted that Sec.100 nowhere uses the term ‘special notice’.

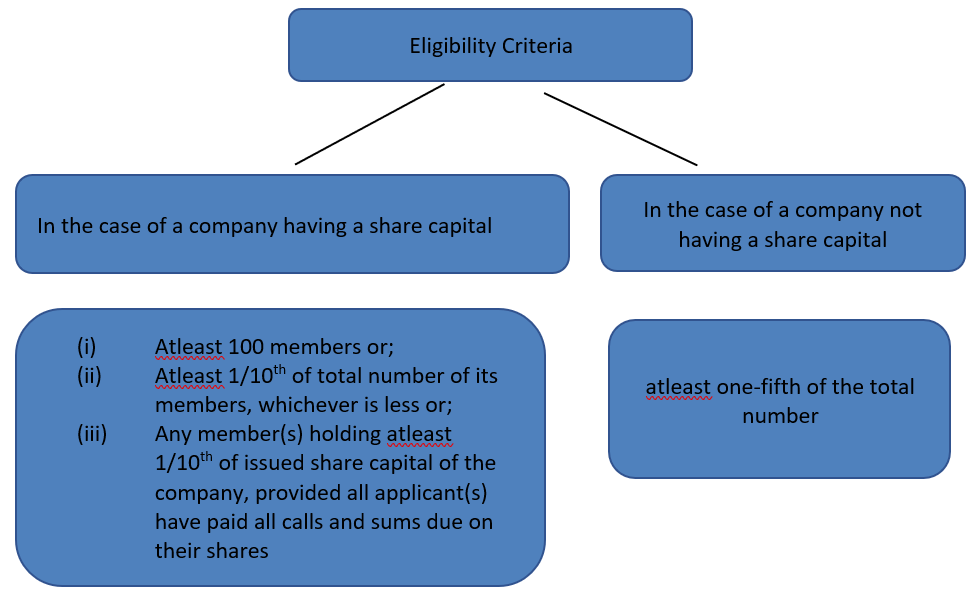

Also, the eligibility criteria prescribed under section 115 is different from what has been provided in section 100 which is tabulated below:

| Eligibility criteria under section 115 |

Eligibility criteria under section 100 |

| ● Members holding not less than 1% of the total voting power or

● Members holding shares on which such aggregate sum not less than 5 lakh rupees, as may be prescribed, have been paid up.

|

● In the case of a company having a share capital;

○ Shareholders holding not less than 1/10th of the paid-up share capital of the company

● In the case of a company not having a share capital;

○ Shareholders holding, on the date of receipt of the requisition, not less than 1/10th of the total voting power of all the members. |

From the above, one can see that the threshold limit prescribed under section 115 is lower as compared to section 100. Thus, a lesser minority will be able to give a special notice for the removal of a director as compared to the requirements of section 100. The intent of the law also makes it more evident that these two provisions are separate and distinct from each other.

The subject matter of section 115 and section 111 are different wherein the former contains the provisions where the Act mandates a special notice for a resolution. However, the purpose under section 100 can be anything except what has been provided in section 115.

Further, section 111 requires that the shareholders shall deposit or tender with the requisition, a sum reasonably sufficient to meet the company’s expenses in giving the notice to all the shareholders of the company. However, there is no such requirement provided in section 115 read with Rule 23.

Under section115 and Rule 23, it has been specifically provided that notice of such requisition shall be given by the company to all the members or if it is not practical to give such notice, it shall be published in two newspapers having circulation at the place where the registered office of the company is located either in English language or in any other regional language of such place. But, there is no such provision in section 111 of the Act.

Also, section 140 of the Act also requires that a special notice is required for appointing a person as an auditor other than a retiring auditor, or providing expressly that a retiring auditor shall not be re-appointed. Such a special notice shall be given as per the provisions of section 115.

The views above have been upheld by the Hon’ble High Courts of India in multiple judgements as stated below:

In Gopal Vyas vs Sinclair Hotels And...: AIR 1990 Cal 45, 1990 68 CompCas 516 Cal[12] The Hon’ble High Court of Calcutta took the view that section 284 is a self-contained provision and the procedure is very specific for removal of a director. The court opined took the view that:

“The procedure for removal of a director has been specially provided in our Companies Act. Section 284 makes specific provision for such removal where special notice is required for any resolution of removal of a director or for appointment of somebody instead of that director so removed at the meeting at which he is removed.”

The view taken by Hon’ble Calcutta High Court in Gopal Vyas vs Sinclair Hotels was also upheld in Karnataka Bank Ltd. vs A.B. Datar And Others: 1994 79 CompCas 417 Kar, 1993 (2) KarLJ 230[13] by The Hon’ble Karnataka High Court:

“A comparative view of the two sections shows that section 284 is an independent provision providing for removal of directors and it is available for any shareholder for moving a resolution for removal of a director in meetings called by the company and there is nothing to insist on compliance with the provisions in section 188(2) to call a meeting to move a resolution as urged. Therefore, prima facie the view of the law to be taken having regard to the provisions of the two sections would be to hold that section 284 of the Companies Act is not subject to section 188 of the Companies Act and it is independent of that section..”

The court held that section 284 which provides for the removal of a director contains nothing to indicate that it is subject to section 188 of the Erstwhile Act.

Section 115 of the Act vs. Section 190 of Erstwhile Act

A comparative analysis of the current section and the provision of Esrtwhile Act also make it much clearer that the new section 115 has been refined to make it a complete procedure wherever the Act has prescribed that a special notice of the members shall be required for a resolution to be passed at a general meeting of the company.

| Section 115 of the Act |

Section 190 of Erstwhile Act |

| ● Prescribes an eligibility criteria for shareholders to give special notice

● Prescribes a cap of 3 months from the date of meeting for issue of such notice

● Prescribes the languages in which the newspaper advertisement has to be published |

● Does not state any specific eligibility criteria

● No upper limit has been provided.

● Does not specify the manner of newspaper advertisement |

Concluding remarks

On a perusal of the aforementioned judicial pronouncements, it can be seen that the removal of director from such office has multiple facets and it is not limited to the process as specified in section 169 of the Act alone. Where the articles of a company bestow upon the directors, the power of removal of a director, such right is unaffected by the provisions of section 169. It is also accepted in the courts that the removal of a director need not specify any reason for such removal to be mentioned in the Explanatory statement to a notice to the shareholders. Thus, the provisions of removal of directors can go beyond section 169 of the Act, 2013 and removal can be done by the board of directors in consonance with section 169 read with section 6 of the Act, 2013. Further, the special notice under section 169 shall be given as per section 115 read with Rule 23 and the provisions of section 111 read with section 100 shall not be applicable for such special notice.

[1] https://www.casemine.com/judgement/uk/5a8ff8c860d03e7f57ecd506

[2] https://indiankanoon.org/doc/1738210/

[3] https://www.casemine.com/judgement/in/5ac5e2bb4a932619d9021946

[4] https://indiankanoon.org/doc/149896839/

[5] https://indiankanoon.org/doc/730804/

[6] https://indiankanoon.org/doc/1477791/

[7] https://indiankanoon.org/doc/709945/

[8] https://indiankanoon.org/doc/1339373/

[9] Resolutions Requiring Special Notice

[10] Circulation of Members’ Resolution

[11] Calling of Extraordinary General Meeting

[12] https://indiankanoon.org/doc/1536641/

[13] https://indiankanoon.org/doc/458102/