Vehicle financiers must follow SARFAESI process for repossession: Patna High Court

Ruling holds self-help repossession as a breach of the borrower’s fundamental rights of livelihood and dignity

– Vinod Kothari, finserv@vinodkothari.com

Repossession of vehicles (from two-wheelers to four-wheelers), in case of borrowers’ defaults, has been done almost entirely using common law process, on the strength of the provisions of the hypothecation agreement. The roughly Rs 500000 crores auto finance market in India, including financing of passenger vehicles and commercial vehicles, rarely makes use of the process of SARFAESI Act for repossession of vehicles from defaulting borrowers, even though most of the NBFCs and all of the banks are authorised to make use of the process.

However, a recent Patna High Court, from a single judge of the Court[1], holds that since hypothecation is a “security interest” on the vehicle, the use of the process of the SARFAESI Act is mandatory, and any repossession action not adhering to the process of that Act is illegal. The Court has gone to the extent of ordaining all banks and NBFCs in the State to return the repossessed vehicles which are either not sold or are traceable to the borrowers on payment of 30% of the due amount, and in case of those vehicles which are not traceable or returnable, it permits the petitioners to seek compensation. It has simultaneously directed the Police to investigate and register cases of use of force or illegal tactics in repossession.

It may be over-optimistic to believe that the force of the ruling is limited to Bihar, and therefore, lenders in other states do not need to take notice. While the basic premise of the ruling, that adherence to the SARFAESI process is mandatory, may eventually not sustain in higher judicial forums, the ruling also highlights several practices which are representative of the entire vehicle finance industry. For instance, several borrower notifications, including handing over the matter to a specific recovery agency in case of banks, pre-repossession notice, pre-sale notice, etc., are either never seriously adhered to, or the notices leave barely any practical time for the borrower to at all pay. Also, while this matter has not been much highlighted in the present ruling, there is a huge opacity in the sale process after repossession, as the vehicles are mostly sold at deeply discounted prices.

Thus, the ruling should touch a very sensitive nerve of the vehicle finance industry – how to handle repossessions. No one could ever expect the act of repossession to be pleasant. No lender loves to do repossessions, as that is truly the last remedy. But lenders have to act in time to prevent vehicle values from depleting in the hands of a truant borrower. And the use of recovery agencies is almost a must, as lenders cannot afford to have their in-house recovery teams across the length and width of the state. Vehicle finance is as much a must for the country’s mobility and logistics needs, as fairness in recovery practices is. The balance between the two is precarious and yet needed.

This article discusses the reason why the SARFAESI process is rarely, if ever, resorted to, in the case of vehicles, the RBI codes for recovery in case of banks and NBFCs, the classic rulings of the SC in the case of Prakash Kaur and Shanti Devi, and the scenario that might emerge after this ruling.

Why is SARFAESI process not followed?

There is no doubt that hypothecation (unlike hire purchase – see below) is a “security interest” under the SARFAESI Act and all banks are covered by the definition of “secured creditors” under that Act. Additionally, NBFCs having assets of Rs.100 crores or more are notified as secured creditors under the law. However, for such eligible NBFCs to be able to enforce security interest, the debts must amount to atleast Rs. 20 lacs. Even in case of other secured creditors under SARFAESI, like banks, the limit is Rs. 1 lac. Therefore, almost every major asset finance lender, and every bank, are entitled to use the process of the SARFAESI Act for repossession. And yet, no one does.

The SARFAESI process, intended to be a non-judicial self-help process for recoveries in case of secured loans, has been found, in practice, to be impractical for vehicle financiers. It requires a 60 days notice, after the loan turns non-performing, after which a lender may do repossession through an “authorised officer”. This itself precludes the use of agencies. Further, there is a minimum of 30 days’ notice before sale, etc.

Practically, lenders do not resort to repossessions the moment a borrower defaults. Repossessions are a costly, and inefficient mode of recovery given the resale price suffering a sharp haircut relative to the fair value of the asset. Hence, most lenders will try to work with the borrower to see that he pays. However, it is a fact that several borrowers are truant, and at times, it is not a case of difficulty in paying but the ability to avoid repossession while defaulting. That is where the use of forced repossession comes in. The trick is to take the borrower by surprise, by having informers who inform the recovery agent of the location of the vehicle while it is on the road or parked on the way.

In case of vehicle loans, for NBFCs, the use of SARFAESI process is ruled out because the loan size is rarely above Rs 20 lacs, except in case of high value assets like buses or construction equipment.

SARFAESI is an enabling legislation; SARFAESI procedure is not mandatory. SARFAESI was enacted to facilitate the recovery of secured assets in case of a default. Therefore, it is contended, unlike what the Patna High Court has concluded, that SARFAESI is not a code of recoveries.

A secured creditor may resort to the remedies listed in sec. 13 (2) of the Act read with sec. 13 (4), but nowhere does the SARFAESI Act suggest that the law is mandatory. Section 13 (2) permits a secured creditor to give a notice as referred to therein but does not mandate the creditor. The remedies under the Act will be available only if the secured creditor follows its process, but the secured creditor does not have to choose the remedy at all. In fact, section 37 of the Act itself provides that the law is in addition to any other law for the time being in force, and not in derogation thereof. The law was designed to speed up recoveries, and not to stifle or stall.

Hence, to contend that SARFAESI Act is the code for recoveries, let alone a “complete code”, is to read SARFAESI Act out of the context in which it was enacted. SARFSAESI does not prohibit or preclude the use of common law remedies.[2]

Hire-purchase and Hypothecation

Hire-purchase has traditionally been used as the instrument for vehicle financing in India. With a history of over 100 years, the hire purchase financiers perfected the art of repossession, which was crucial for their existence. There are several rulings of courts, including those from the Supreme Court (one, in the case of Magma Finance v. Rajesh Kumar Tiwari, has been cited by the Patna High Court ruling itself), where the courts have drawn on the ownership of the vehicle remaining with the financier. So, if there is a default, it is the lawful owner of the vehicle taking repossession, which cannot be faulted with.

Hire-purchase, however, is no longer practiced. It became unpopular with the advent of sales tax on hire purchases, followed by GST. Currently, most of the vehicle finance agreements are modeled as hypothecations, though some traditional NBFCs may still be using at least some remnants of the hire-purchase jargon, referring to the borrower as “hirer”, etc.

Use of recovery agencies: Concerns

Repossession in case of asset finance transactions is done by either the lender’s own machinery or by the so-called “recovery agents”. The repossession action may almost be the stuff for a thriller movie: starting from tracing the vehicle through an intricate network of informers, to choosing the best time (ideally when it is parked, not occupied or not loaded, etc.), to actually driving the vehicle away keeping the police in the loop. Needless to say, it is impossible for a bank or an NBFC to handle all of this by itself. Hence, the use of recovery agencies.

Purely talking about the right of repossession in case of hypothecations, courts have regarded hypothecation as a case of juridical possession with the lender, and physical possession with the borrower. If the contract of hypothecation provides for a right of repossession, the lender may enforce that contractual right without judicial intervention. This classic rule was discussed by the AP High Court in State Bank of India vs S B Shah Ali. However, when the recovery agencies step in, the issue mostly hinges on the use of force, and this is where the focus of the judiciary shifts from the pristine principles of secured lending to whether the process used for recovery was alright. The next 2 cases, which have set the backdrop to Patna High Court ruling, are both on practice rather than principles.

In the case ofICICI Bank Ltd. v. Prakash Kaur and Ors. (2007), the vehicle with the defaulting petitioner was taken away from the petitioner by force employing “musclemen”. This is a common expression in almost every litigation that agitates against repossession. The Supreme Court deprecated the practice adopted by banks of taking forcible possession of vehicles by hiring recovery agents. It ruled that neither force can be utilized nor musclemen or hooligans can be hired by a private or nationalized bank in order to recover the amount of a loan.

Around this time, National Consumer Disputes Redressal in the matter of Citicorp Maruti Finance Ltd. vs S. Vijayalaxmi on 27 July 2007 stated that, on occasions, borrower suffers harassment, torture, or abuses at the hands of the musclemen of the moneylender. Such a behavior is required to be prohibited and the process of repossession is required to be streamlined so as to fit into a culturally civilized society. Let the rule of law prevail and not that of the jungle where might is right.

A year after the Prakash Kaur ruling, another landmark judgment on this issue was delivered by the Supreme Court in ICICI Bank vs Shanti Devi Sharma & Ors (2008). In this case, the recovery agents of ICICI Bank forcibly took possession of a vehicle financed by the bank from the borrower’s residence without any legal authority or due process. The Appelant’s son committed suicide due to the humiliation faced by him in front of family and neighbors by the recovery agents. The Supreme Court condemned this practice and held that banks must resort to the procedure recognized by law to take possession of vehicles in case of default, instead of using musclemen or strong-arm tactics. The court also suggested that banks should be vicariously liable for the unlawful acts of their recovery agents and that the RBI should take strict action against such violations.

These judgments highlight the need to maintain a balance between the rights and interests of both lenders as well as borrowers in matters of loan recovery. While lenders have a legitimate right to recover their dues, they cannot resort to illegal or unethical means that violate the rule of law and human rights.

RBI lays codes of conduct

The Apex court’s rulings above triggered the codes for recovery agencies by the RBI. Considering the rise in the number of customer grievances in relation to the recovery practices of the lenders, the RBI issued a notification on August 12, 2022 on Outsourcing of Financial Services – Responsibilities of regulated entities employing Recovery Agents which provided a consolidated list of the various existing guidelines/directions issued by the regulator. Particularly, it was conveyed by the regulator that the lenders should strictly ensure that they or their agents do not resort to intimidation or harassment of any kind, either verbal or physical, against any person in their debt collection efforts.

The following action of the recovery agents was highlighted to be discouraged:

- humiliate publicly,

- intrude upon the privacy of the debtors’ family members, referees and friends,

- sending inappropriate messages either on mobile or through social media,

- making threatening and/ or anonymous calls, persistently/repeatedly calling the borrower and/ or calling the borrower before 8:00 a.m. and after 7:00 p.m. for recovery of overdue loans etc.

While there are detailed guidelines on recovery agents engaged by banks, the same is not ad verbatim extended to NBFCs. For banks, there is a requirement to inform the borrower of the details of recovery agency firms/companies while forwarding default cases to the recovery agency. Further, the agent is also required to carry a copy of the notice and the authorization letter from the bank along with the identity card issued to him by the bank or the agency firm/company. Banks are further advised to ensure that there is a tape recording of the calls made by recovery agents to the customers, and vice-versa, with prior intimation to the customer. It has also been suggested that the up-to-date details of the recovery agency firms/companies engaged by banks be posted on the bank’s website.

It would be interesting to note that the RBI had while making reference to the SARFAESI provisions for enforcement of security interest in case of movable as well as immovable properties, stated that ‘it is desirable that banks rely only on legal remedies available under the relevant statutes while enforcing security interest without intervention of the Courts.’

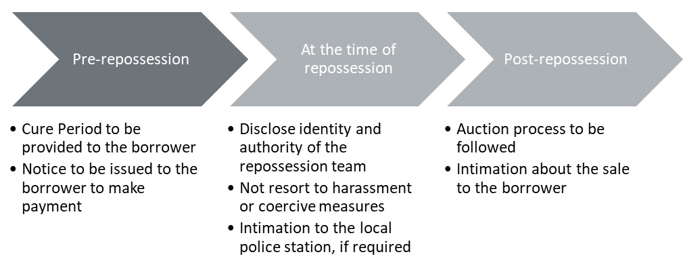

However, the guidelines are not very detailed in the case of NBFCs. The Outsourcing Guidelines require NBFCs to put in place a board-approved code of conduct for recovery agents and obtain their undertaking to abide by the code. Though there is a requirement to properly train the agents to handle their responsibilities with care and sensitivity, particularly aspects such as hours of calling, the privacy of customer information etc., there is no formal training module or certification course prescribed as such. The code of conduct usually provides generic guidance to the recovery agents. A sample process flow for repossession is provided herein below:

Patna High Court holds SARFAESI is mandatory

The case of Shashi Kant Kumar (supra) is a bunch of cases by various borrowers, but as may be intuitive, each of these involves the use of self-help, non-SARFAESI repossession by either banks or NBFCs. As no repossession can be expected to be a sweet meeting, there are allegations of use of force in each case. Further, it is hardly surprising to see the borrower contending there was cash in the vehicle which was taken away, or occupants including women and children were made to vacate, etc.

There are certain other factual matters, where the weak spot of recovery practices commonly deployed by the recovery agencies becomes clear. First, their police report about the default and intended repossession is tactically filed the same day as the day of repossession. Second, after repossession, the sale is done briskly, and at haircut values, as one cannot expect a repossessed vehicle to be sold at fair values.

While these apparent malpractices have been highlighted by the court, the court has majorly focused on whether the use of SARFAESI process is mandatory, since hypothecation amounts to a “security interest”.

The court held that the SARFAESI Act is a complete code in itself and overrides any other law or contract to the contrary. The court further noted that the SARFAESI Act confers a statutory right on the secured creditors to take possession and sell the secured assets without recourse to courts, subject to certain conditions and safeguards. The court held that this right is not merely an additional or alternative remedy, but a mandatory and exclusive remedy for recovery of secured debts.

Some relevant extracts:

| “The covenants of the loan agreement providing for re-possessing the vehicle do not provide for a procedure in accordance with the provisions of the Act of 2002 and the Rules framed thereunder. In the garb of a power acquired by the financier under the loan agreement to repossess the vehicle, they cannot be allowed to take the law into their hands and enforce the loan agreement by violating the legislative mandate and the regulatory law such as as the Act of 2002.” [para 59] |

The Patna High Court was relying on an earlier ruling of the Court in the case of Sujay Kumar vs UCO Bank. Here, the same Judge of the court was dealing with the matter of repossession of two air-conditioned buses funded by UCO Bank, for which there were recurring defaults. The court in the earlier had also held that the use of the SARFAESI process is mandatory.

In the instant case, the court concluded that the suit filed by the bank was not maintainable and liable to be dismissed. The court directed the bank to withdraw the suit and proceed under the SARFAESI Act for recovery of its dues. The court also imposed costs on the bank for filing a frivolous suit. The relevant extort of the ruling is as follows:

“Since this Court has come to a conclusion that the covenants in the loan agreement of these cases are at best creating a ‘security interest’ in the ‘secured asset’ i.e. the vehicle in favour of the Banks and Financial Institutions, as the case may be, this Court directs that the Banks/Financial Institutions who are contesting respondents in these cases shall henceforth, exercise their power to seize and repossess the vehicle only in accordance with the provisions of the Act of 2002, and the Rules framed thereunder and the RBI guidelines. Their right to seize or re-possess is not in question, it is the manner in which it is being exercised is illegal, hence, they cannot continue with the same.” [para 65]

Way forward

The world of unsecured lending largely has been depending on credit bureau scores to ensure compliant borrower behavior. Hopefully, vehicle financiers may make better use of technology. The use of GPS locators has already become quite common; it may not be difficult to evolve disabling devices too, which may cause a vehicle key to be disabled by using technological tools.

Nevertheless, at some stage, a lender may have to repossess and sell too. No one can claim default on a loan to be a fundamental right; it is also a settled principle that the one who comes claiming equity and justice must come with clean hands. When it is an admitted fact that the borrower is in default and that too, continuing one, he cannot be sitting on the high pedestal of equity and dignity. However, in civil societies, defaulting on a debt is not a crime, which is exactly why the law gives every defaulter a fair chance to make a fresh start. While a defaulter has to lose the asset funded with a defaulted loan, the issue is -was he given a fair chance to pay after notice, and post repossession, whether there was a fair attempt to sell the vehicle at fair value, including by giving a chance to the borrower to put up his preferred buyer.

There is a code of conduct of FIDC; there are detailed codes of the RBI, but surely, there is a need for vehicle financiers to introspect and evolve better methods. For example, can the borrower, who is anyways unable to clear his dues, be motivated to put the vehicle for sale on a second hand vehicle marketplace, at least to realise the fair value of the vehicle? If that does not happen, can the vehicle be sold through one of these marketplaces, rather than through private sale, because the real cause of concern is the under-realisation of vehicle value.

[1] Shashi Kant Kumar vs The State Of Bihar on 19 May, 2023

[2] Refer to our FAQs on SARFAESI Act for NBFCs which clarifies that SARFAESI Act only provides a mode of enforcement of security interest and does not bind the secured creditor to use nothing but SARFAESI Act. Therefore, NBFCs can avoid using SARFAESI Act and enforce security interests under common law principles. https://vinodkothari.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/SARFAESI-Act-for-NBFCs.pdf

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!