RBI aligns list of compoundable contraventions under FEMA with NDI Rules

/0 Comments/in Corporate Laws, FEMA, RBI /by Vinod Kothari Consultants‘Technical’ contravention subject to minimum compoundable amount, format for public disclosure of compounding orders revised.

– CS Burhanuddin Dohadwala | corplaw@vindkothari.com

Introduction

Compounding refers to the process of voluntarily admitting the contravention, pleading guilty and seeking redressal. It provides comfort to any person who contravenes any provisions of FEMA, 1999 [except section 3(a) of the Act] by minimizing transaction costs. Reserve Bank of India (‘RBI’) is empowered to compound any contraventions as defined under section 13 of FEMA, 1999 (‘the Act’) except the contravention under section 3(a) of the Act in the manner provided under Foreign Exchange (Compounding Proceedings) Rules, 2000. Provisions relating to compounding is updated in the RBI Master Direction-Compounding of Contraventions under FEMA, 1999[1].

Following are few advantages of compounding of offences:

- Short cut method to avoid litigation;

- No further proceeding will be initiated;

- Minimize litigation and reduces the burden of judiciary;

Present Circular

Pursuant to the supersession of FEM (Transfer or Issue of Security by a Person Resident Outside India) Regulations, 2017[2] (‘TISPRO”)and issuance of FEM (Non-Debt Instrument) Rules, 2019[3] [‘NDI Rules] and FEM (Mode of Payment and Reporting of Non-Debt Instruments) Regulations, 2019[4] [‘MPR Regulations’], RBI has updated the reference of the erstwhile regulations in line with the NDI Rules and MPR Regulations vide RBI Circular No.06 dated November 17, 2020[5] (‘Nov 2020 Circular’).

Additionally, the Nov 2020 Circular does away with the classification of a contravention as ‘technical’, as discussed later in the article.

Lastly, the Nov 2020 Circular modifies the format in which the compounding orders will be published on RBI’s website.

Compounding of contraventions relating to foreign investment

The power to compound contraventions under TISPRO delegated to the Regional Offices/ Sub Offices of the RBI has been aligned with corresponding provisions under NDI Rules and MPR Regulation as under:

| Compounding of contraventions under NDI Rules | |||

| Rule No. | Deals with | Corresponding regulation under TISPRO | Brief Description of Contravention |

| Rule 2(k) read with Rule 5 | Permission for making investment by a person resident outside India; | Regulation 5 | Issue of ineligible instruments |

| Rule 21 | Pricing guidelines; | Paragraph 5 of Schedule I | Violation of pricing guidelines for issue of shares. |

| Paragraph 3 (b) of Schedule I | Sectoral Caps; | Paragraph 2 or 3 of Schedule I | Issue of shares without approval of RBI or Government respectively, wherever required. |

| Rule 4 | Restriction on receiving investment; | Regulation 4 | Receiving investment in India from non-resident or taking on record transfer of shares by investee company. |

| Rule 9(4) | Transfer by way of gift to PROI by PRII of equity instruments or units of an Indian company on a non- repatriation basis with the prior approval of the Reserve Bank. | Regulation 10(5) | Gift of capital instruments by a person resident in India to a person resident outside India without seeking prior approval of the Reserve Bank of India. |

| Rule 13(3) | Transfer by way of gift to PROI by NRI or OCI of equity instruments or units of an Indian company on a non- repatriation basis with the prior approval of the Reserve Bank. | ||

| Compounding of contraventions under MPR Regulations | |||

| Regulation No. | Deals With | Corresponding regulation under TISPRO | Brief Description of Contravention |

| Regulation 3.1(I)(A) | Inward remittance from abroad through banking channels; | Regulation 13.1(1) | Delay in reporting inward remittance received for issue of shares. |

| Regulation 4(1) | Form Foreign Currency-Gross Provisional Return (FC-GPR); | Regulation 13.1(2) | Delay in filing form FC (GPR) after issue of shares. |

| Regulation 4(2) | Annual Return on Foreign Liabilities and Assets (FLA); | Regulation 13.1(3) | Delay in filing the Annual Return on Foreign Liabilities and Assets (FLA). |

| Regulation 4(3) | Form Foreign Currency-Transfer of Shares (FC-TRS); | Regulation 13.1(4) | Delay in submission of form FC-TRS on transfer of shares from Resident to Non-Resident or from Non-resident to Resident. |

| Regulation 4(6) | Form LLP (I); | Regulations 13.1(7) and 13.1(8) | Delay in reporting receipt of amount of consideration for capital contribution and acquisition of profit shares by Limited Liability Partnerships (LLPs)/ delay in reporting disinvestment / transfer of capital contribution or profit share between a resident and a non-resident (or vice-versa) in case of LLPs. |

| Regulation 4(7) | Form LLP (II); | ||

| Regulation 4(11) | Downstream Investment | Regulation 13.1(11) | Delay in reporting the downstream investment made by an Indian entity or an investment vehicle in another Indian entity (which is considered as indirect foreign investment for the investee Indian entity in terms of these regulations), to Secretariat for Industrial Assistance, DIPP. |

Technical contraventions to be compounded with minimal compounding amount

As per RBI’s FAQs[1] whenever a contravention is identified by RBI or brought to its notice by the entity involved in contravention by way of a reference other than through the prescribed application for compounding, the Bank will continue to decide (i) whether a contravention is technical and/or minor in nature and, as such, can be dealt with by way of an administrative/ cautionary advice; (ii) whether it is material and, hence, is required to be compounded for which the necessary compounding procedure has to be followed or (iii) whether the issues involved are sensitive / serious in nature and, therefore, need to be referred to the Directorate of Enforcement (DOE). However, once a compounding application is filed by the concerned entity suo moto, admitting the contravention, the same will not be considered as ‘technical’ or ‘minor’ in nature and the compounding process shall be initiated in terms of section 15 (1) of Foreign Exchange Management Act, 1999 read with Rule 9 of Foreign Exchange (Compounding Proceedings) Rules, 2000.

Nov 2020 Circular provides for regularizing such ‘technical’ contraventions by imposing minimal compounding amount as per the compounding matrix[1] and discontinuing the practice of giving administrative/ cautionary advice.

Public disclosure of compounding order

Compounding order by RBI can be accessed at the RBI website-FEMA tab-compounding orders[1]. In partial modification of earlier instructions issued dated May 26, 2016[2] it has been decided that in respect of the Compounding Orders passed on or after March 01, 2020 a summary information, instead of the compounding orders, shall be published on the Bank’s website in the following format:

| Sr. No. | Name of the Applicant | Details of contraventions (provisions of the Act/Regulation/Rules compounded)

(Newly inserted) |

Date of compounding order

(Newly inserted) |

Amount imposed for compounding of contraventions | Download order

(Deleted) |

It seems that the compounding order will not be available for download.

Conclusion:

The delegation of power is done for enhanced customer service and operational convenience. Revised format of disclosure of compounding orders will be more reader friendly. Delay in filing of forms under MPR Regulations on FIRMS portal is subject to payment of Late Submission Fees (LSF) as per Regulation 5. The payment of LSF is an additional option for regularising reporting delays without undergoing the compounding procedure.

Abbreviations used above:

- PROI: Person Resident Outside India;

- PRII: Person Resident In India;

- NRI: Non-Resident Indian;

- OCI: Overseas citizen of India;

FIRMS: Foreign Investment Reporting & Management System.

| Our other articles/channel can be accessed below:

1. Compounding of Contraventions under FEMA, 1999- RBI delegates further power to Regional Offices:

2. Other articles on FEMA, ODI & ECB may be access below: http://vinodkothari.com/category/corporate-laws/

3. You Tube Channel: |

[1] https://www.rbi.org.in/scripts/Compoundingorders.aspx

[2] https://www.rbi.org.in/Scripts/NotificationUser.aspx?Id=10424&Mode=0

[1] https://www.rbi.org.in/Scripts/NotificationUser.aspx?Id=10424&Mode=0

[1] https://m.rbi.org.in/Scripts/FAQView.aspx?Id=80 (Q. 12)

[1] https://www.rbi.org.in/Scripts/BS_ViewMasDirections.aspx?id=10190

[2] https://www.rbi.org.in/Scripts/NotificationUser.aspx?Id=11253&Mode=0

[3] http://egazette.nic.in/WriteReadData/2019/213332.pdf

[4] https://www.rbi.org.in/Scripts/BS_FemaNotifications.aspx?Id=11723

[5]https://rbidocs.rbi.org.in/rdocs/notification/PDFs/APDIRS62545AA7432734B31BD5B59601E49AA6C.PDF

New Model of Co-Lending in financial sector

/0 Comments/in Financial Services, NBFCs, RBI, Uncategorized /by Vinod Kothari ConsultantsScope expanded, risk participation contractual, borders with direct assignment drawn

-Team Financial Services (finserv@vinodkothari.com)

[This version dated 20th March, 2021]

Co-lending is coming together of entities in the financial sector – mostly, something that happens between banks and NBFCs, or larger banks and smaller banks. Financial interfaces between different financial entities may take the form of securitisation, direct assignment, co-lending, banking correspondents, loan referencing, etc.

While direct assignment and securitisation have been around for quite some time, co-lending was permitted by the RBI under its existing guidelines on ‘Co-origination of loans between banks and NBFC-SIs for granting loan to the priority sector’[1]. As per the Statement on Developmental and Regulatory Policies issued by the RBI dated October 9, 2020, it was decided to expand the scope of co-lending, currently permitted only for NBFC-SIs, to all NBFCs. Accordingly, the RBI came, vide notification on co-lending by banks and NBFCs (Co-Lending Model/CLM)[2] dated November 5, 2020, with a new regulatory framework for co-lending, of course, in case of priority sector loans. The CLM supersedes the existing guidelines on co-origination.

There is no clarity, still, on whether the non-priority sector loans (PSL or Non-PSL) will also be covered by this regulatory discipline, or any discipline for that matter. In this write-up, we explore the key features of the co-lending regime, and also get into tricky questions such as applicability to non-PSL loans, the borderlines of distinction between direct assignments and co-lending, the sharing of risks and rewards, etc.

Applicability

The erstwhile Regulations for priority sector lending covered co-lending transactions of Banks and Systemically Important NBFCs. However, under the Co-Lending Model.The CLM covers all NBFCs (including HFCs) in its purview.

There is a whole breed of new-age fintech companies using innovative algo-based originations, and aggressively using the internet for originations, and these companies pass a substantial part of their lending to either larger NBFCs or to banks. Thus, the expanded ambit of the Co-Lending Model will increase the penetration and result into wider outreach, meet the objective of financial inclusion, and potentially, reduce the cost for the ultimate beneficiary of the loans. Smaller NBFCs have their own operational efficiencies and distribution capabilities; hence, this is a welcome move.

Further, the RBI has excluded foreign Banks, including wholly owned subsidiaries of foreign banks, having less than 20 branches, from the applicability of the CLM. Also, Small Finance Banks, Regional Rural Banks, Urban Cooperative Banks and Local Area Banks have been excluded from the applicability of CLM.

An interesting question that comes up here is whether such exclusion should be construed as a restriction on such entities from entering into co-lending transactions, or a relaxation from the applicability of the Co-Lending Model? It may be noted that the CLM a precondition for PSL treatment of the loans. This is clear from the title ‘Co-Lending by Banks and NBFCs to Priority Sector’. The intent is not to put a bar on existence of co-lending arrangements outside the CLM. That is to say, if the loan, originated by the principal co-lender, is a priority sector loan, then the participating co-lender will also be able to treat the participant’s share of the loan as a PSL, subject to adherence to the conditions specified in CLM. The implication of this is that where the loan does not meet the conditions of CLM, then the participating bank will not be able to accord a PSL status, even though the loan in question is a PSL loan.

With that rationale, in our view, there is no absolute prohibition in the excluded banking entities from being a co-lender. However, if the major motivation of the co-lending mechanism under the CLM is the PSL tag, that tag will not be available to the excluded banks, and hence, the very inspiration for falling under the arrangement may go away. This is also clear from the PSL Master Directions[3] which recognises co-origination of loans by SCBs and NBFCs for lending to the priority sector and specifically excludes RRBs, UCBs, SFBs and LABs.

Applicability date and the fate of existing transactions

In the absence of any specified timelines, the CLM supersedes the existing co-lending guidelines with immediate effect. However, it specifies that outstanding loans in terms of the erstwhile guidelines would continue to be classified under priority sector till their repayment or maturity, whichever is earlier.

This would mean grandfathering of existing loans, and not existing lending arrangements. That is to say, if there are existing co-lending arrangements, but the loan in question has not yet originated, even existing co-lending arrangements will have to abide with the Co-Lending Model. Needless to say, any new co-lending arrangements will nevertheless have to abide by the Co-Lending Model.

As we note below, one of the very important features of the Co-Lending Model is that risk-sharing and loan-sharing do not have to follow the same proportion. Additionally, it is possible for the participating bank to have an explicit recourse against the originating co-lender. This feature was not available under the earlier framework. This alone may be a sufficient motivation for existing CLMs to be revised or redrawn.

Co-lending, Outsourcing and Direct Assignment – new borderlines of distinction

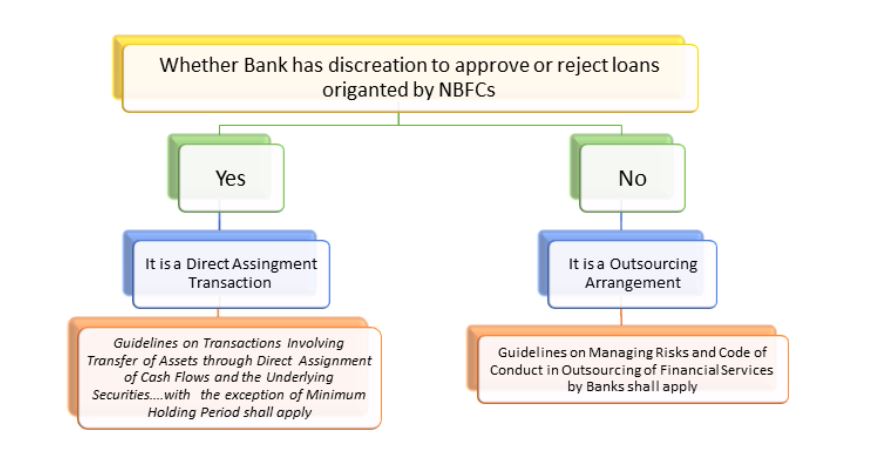

For the purpose of entering into co-lending transactions, banks and NBFCs will have to enter into a ‘Master Agreement’. Such agreement may require the bank either to mandatorily take the loans originated by the NBFC on its books or retain discretion as to taking the loans on its books.

Where the participating bank has a discretion as to taking its share of the loans originated by the originating partner, the transaction partakes the character of a direct assignment. Para 1(c) of the CLM says that ”…if the bank can exercise its discretion regarding taking into its books the loans originated by NBFC as per the Agreement, the arrangement will be akin to a direct assignment transaction. Accordingly, the taking over bank shall ensure compliance with all the requirements in terms of Guidelines on Transactions Involving Transfer of Assets through Direct Assignment of Cash Flows and the Underlying Securities….with the exception of Minimum Holding Period (MHP) which shall not be applicable in such transactions undertaken in terms of this CLM.

That would mean, a precondition for the arrangement being treated as a CLM is that the participating bank takes the loans originated by the originating partner without discretion exercisable on a cherry-picking basis.

Does this mean that irrespective of whether the loan originated by the originating partner fits into the credit screen of the bank or not, the bank will still have to take it, lying low? certainly, this is not the intent of the CLM This is what comes form clause 1(a)- ‘…..the partner bank and NBFC shall have to put in place suitable mechanisms for ex-ante due diligence by the bank as the credit sanction process cannot be outsourced under the extant guidelines.’

Thus, even in case the bank gives a prior, irrevocable commitment to take its share of exposure, the same shall be subject to an ex-ante due diligence by the bank. Ex-ante obviously implies a prior As per the outsourcing guidelines for banks[4], the credit sanction process cannot be outsourced. Accordingly, it must be ensured that the credit sanction process has not been outsourced completely and the bank retains the right to carry out the due diligence as per its internal policy. Notwithstanding the bank’s due diligence exercise, the co-lending NBFC shall also simultaneously carry out its own credit sanction process.

The conclusion one gets from the above is as follows:

- The essence of co-lending arrangement is that the participating bank relies upon the lead role played by the originating bank. The originating bank is the one playing the fronting role, with customer interface. The credit screens, of course, are pre-agreed and it will naturally be incumbent upon the originating bank to abide by those. Hence, on a case by case basis or so-called “cherry picking” basis, the participating bank is not selecting or dis-selecting loans. If that is what is being done, the transaction amounts to a DA.

- Subject to the above, the participating bank is expected to have its credit appraisal process still on. Where it finds deviations from the same, the participating bank may still decline to take its share.

It is important to note that if DA comes into play, the requirements such as MHP, MRR, true sale conditions will also have to be complied with. However, co-lending transactions do not have any MHP requirements, unlike in case of either DA or securitiastion. Of course co-lending transactions do have a risk retention stipulation, as the CLM require a 20% minimum share with the originating NBFC. Hence, the intent of the RBI is that co lending mechanism must not turn out to be a regulatory arbitrage to carry out what is virtually a DA, through the CLM.

(Almost) A new model of direct assignments: assignments without holding period

Para 1 c. of the Annex seems to be leading to a completely new model of direct assignments – direct assignments without a holding period, or so-called on-tap direct assignments. Reading para 1 c. suggests that while co-lending takes the form of a loan sharing at the very inception, the reference in para 1 c. is to loans which have already been originated by the NBFC, and the participating bank now cherry-picks some or more of those loans. The cherry-picking is evident in “if the bank can exercise its discretion regarding taking into its books the loans originated by NBFC”. However, unlike any other direct assignment, this assignment happens on what may be called a back-to-back arrangement, that is, without allowing for lapse of time to see the loan in hindsight.

In essence, there emerge 3 possibilities:

- A non-discretionary loan sharing, which is the usual co-lending model, where the originating co-lender has a minimum 20% share.

- A discretionary, on-tap assignment, where the originating assignor needs to have a minimum 20% share

- A proper direct assignment, with minimum holding period, where the assignor needs to have a minimum 10% share.

The on-tap assignment referred to above seems to be subject to all the norms applicable to a direct assignment, other than the minimum holding period.

Interest Rates

The erstwhile guidelines require that the interest rate charged on the loans originated under the co-lending guidelines would be calculated as per Blended Interest Rate Calculations, that is to say the rate shall be calculated by assigning weights in proportion to risk exposure undertaken by each party, to the benchmark interest rate of the respective lender.

The current guidelines require that the interest rate shall be an all inclusive rate that is mutually agreed by the parties. However it shall be ensured that the interest rate charged is not excessive as the same would breach the provisions of fair practice code, which is to be compulsorily complied.

This change would provide flexibility to the lenders and also ensure that the cost incurred in tracing and disbursals to remote sectors as well as enhanced risk exposure is appropriately compensated.

Determining the roles

Under the erstwhile provisions, it was mandatory that the share of the co-lending NBFC shall be at least 20%. The same has been retained in the CLM as well, requiring NBFCs to retain a minimum of 20% share of the individual loans on their books.

Under the CLM, the co-lending NBFC shall be the single point of interface for the customers. Further, the grievance redressal function would also have to be carried out by the NBFC.

Operational Aspects

Escrow Account

For the purpose of disbursals, collections etc. an escrow account should be opened. The co-lending banks and NBFCs shall maintain each individual borrower’s account for their respective exposures. It is only for the purpose of avoiding commingling of funds, that an escrow mechanism is required to be placed. The bank and NBFC shall, while entering into the Master Agreement, lay down the rights and duties relating to the escrow account, manner of appropriation etc.

Creation of Security

The manner of creation of charge on the security provided for the loan shall be decided in the Master Agreement itself.

Accounting

Each of the lenders shall record their respective exposures in their books. The asset classification and provisioning shall also be done for the respective part of the exposure. For this purpose, the monitoring of the accounts may either be done by both the co-lenders or may be outsourced to any one of them, as agreed in the Master Agreement. Usually, the function of monitoring remains with the NBFC (since, it has done the origination and deals with the customer.)

Non-PSL loans: whether the framework would apply in pari materia?

The guidelines on CLM have been issued for co-lending of loans that qualify for the purpose of priority sector lending. This does not bar lenders from entering into co-lending transactions outside the purview of these guidelines. The only difference it would make is such loans would not be eligible to be classified as loans to the priority sector (which is the primary motive for banks to enter into co-lending transactions).

This seems to form a view that the guidelines would not at all be applicable in case of non-priority sector loans. However, for a transaction to be a co-lending transaction, there has to be adequate risk sharing between the co-lenders. Hence, the guidelines on CLM shall be applicable in pari-materia.

[1] https://www.rbi.org.in/Scripts/NotificationUser.aspx?Id=11376&Mode=0

[2] https://www.rbi.org.in/Scripts/NotificationUser.aspx?Id=11991&Mode=0

[3] https://www.rbi.org.in/Scripts/NotificationUser.aspx?Id=11959&Mode=0

[4] https://www.rbi.org.in/scripts/NotificationUser.aspx?Id=3148&Mode=0

Other related write-ups:

FAQs on restructuring of securitised loans

/0 Comments/in Financial Services, RBI, Securitisation /by Vinod Kothari Consultants– Kanakprabha Jethani, Ass. Manager

(finserv@vinodkothari.com)

Background

The first half of this financial year came with lots of schemes to “apparently” support the financial sector during this time of crisis starting from moratoriums, restructuring, interest subvention and so much more. All these schemes were then adorned with an extension of their time limits, so much that at one point the borrower would altogether tend to forget he has an outstanding liability with some lender.

While the credit risk is an issue lenders cannot ignore, they also cannot ignore the fact that a huge chunk of their borrowers are not going to or will not be able to pay. Considering this, they are bound to allow moratoriums and offer restructuring benefits to them.

A lending transaction is between the lender and the borrower. Providing benefits such as moratorium, restructuring etc. is a matter of agreement between the two. However, in certain cases where there is an involvement of external parties, such as in the case of securitisation or direct assignment of a loan pool, practical dfficulties may arise.

The following FAQs intend to answer the basic questions regarding providing the restructuring benefit to borrowers of loans that have been securitised/assigned by the originator.

Stage1: While contemplating the decision to provide benefit of the schemes

1. Can the originator provide such benefit?

The originator retains/invests in a very small portion of the portfolio. The rest of it is sold off to the assignee/SPV. The moment an originator sells off the assets, all its rights over the assets stand relinquished. However, after the sale, it assumes the role of a servicer. Legally, a servicer does not have any right to confer any relaxation of the terms to the borrowers or restructure the facility.

Therefore, if at all the originator/ servicer wishes to extend moratorium to the borrowers, it will have to first seek the consent of the investors or the trustees to the transaction, depending upon the terms of the assignment agreement.

On the other hand, in the case of the direct assignment transactions, the originators retain only 10% of the cash flows. The question here is, will the originator, with a 10% share, be able to grant moratorium? The answer again is No. With just 10% share in the cash flows, the originator cannot suo-moto grant moratorium, hence, approval of the assignee has to be obtained.

2. Is approval of investors required?

As discussed above, when an asset is securitised/assigned, the investor becomes the ultimate owner of the asset to the extent of his/her investment in the said asset. Hence, any change in the terms of the loan impacts the rights/liabilities of such investors. Hence, the investors, being the actual owners of the asset, must agree to offer the benefit of any restructuring, moratorium etc.

As for schemes which provide an additional/separate credit facility to the existing borrower such as ECLGS scheme[1], such facilities are treated as separate facilities and are not linked with the existing loans (the one which is securitised). Hence, in such cases, the approval of the investor or trustee shall not be required. However, it is recommended that a NOC is obtained from the investor or trustee to the effect that the originator is providing the additional funding based on the existing lending exposure on the borrower.

3. How will the approval be obtained ?

The investors may decide on the manner of providing approval. The originator, in the capacity of the investor (to the extent of retention in the transaction), may propose and initiate the process and obtain approval of other investors.

4. Is it mandatory for the investor to approve?

The investors, like in any other investment, has the right to consider their benefits and losses and accordingly decide on whether to approve. Further, investors may also give conditional approvals, say a change in payout structure, alteration of interest rate etc., considering the increased risk and the fact that investor is, for the time being, foregoing its returns.

5. What happens if investors do not agree?

In case the investors do not agree, no benefit of restructuring/moratorium can be provided to the borrower. But, considering the liquidity crunch in the economy, it is very likely that the borrower will fail to pay the loan instalments, thereby resulting in reduced cashflows from the borrower. However, in case the investors did not agree to grant restructuring benefits and amend the payout structure, they will have to be paid. This would call for the credit support to be utilised. Over time, when credit enhancement is utilised, the rating of the PTCs may be downgraded.

6. What happens if investors agree?

In case the investors agree for providing the benefit to the borrower, the same shall come be put into effect by a revision in payout structure for the investors. The payout structure will be revised as per the terms of restructuring or moratorium as the case may be.

7. What happens with the remaining investors if the majority agrees?

The assignment agreement usually provides the nature of approval required to amend the payment terms- either majority or else 100% of the investor, either in number or in value (usually 100%). Hence, in case the majority has agreed, the rest of the investors shall have to bear the outcome of moratorium/restructuring.

Implementation stage:

8. What will be the immediate impact on investors agreeing to provide the benefit?

When the investors agree for providing any such benefits, they simultaneously agree for an added arrangement concerning the payout structure. Hence, the immediate impact shall be on the cashflows arising out of the underlying assets.

9. What will be the impact on the agreed payout structure?

The payouts may be reduced or deferred or structured in any other way as per the restructuring terms.

10. Can the investors in a securitisation transaction agree for moratorium/restructuring but not for reschedulement or recomputation of payout structure?

In case the investors agree for moratorium/restructuring, such approval would inherently come with reschedulement or recomputation of the payout structure. This is because, if moratorium/restructuring benefit is provided, the cashflows on the underlying asset would be impacted. This, in turn, would affect the cashflows in the securitisation transaction. Hence, when agreeing to provide the benefit to the borrower, investors must bear in mind that there would be a simultaneous change in their payout structure as well.

11. Can the credit enhancements be used to make payments to the investors in case they have agreed to provide the benefit?

Credit enhancements are utilised usually when there is a shortfall due to credit weakness of the underlying borrower(s). In case the investor have agreed for the restructuring, consequently the payout structure must have also been revised and hence, avoiding any default leading to utilisation of the credit enhancement. Irrespective of granting the restructuring benefit, if there is still default, though credit enhancements can be utilised, however, it will reduce the extent of support, weaken the structure of the transaction and may lead to rating downgrade.

12. What will be the impact on the rating of the transaction?

Usually, any delays in payout, defaults etc. lead to a downgrade in the rating of the transaction. However, here it is important to consider that in a securitisation or a direct assignment, the transaction mirrors the quality of the underlying pool. Now, in case of moratorium, there will be a standstill on asset classification and in case of restructuring, the asset classification will be upgraded to standard. Hence, there is no impact on the credit quality of the underlying asset.

If the credit quality of the loans remain intact, then there is no question of the securitisation or the direct assignment transaction going bad. Therefore, we do not see any reason for rating downgrade as well.

Further, the SEBI had on March 30, 2020, issued a circular[2] directing rating agencies to not consider delays/defaults caused due to COVID disruption, as a default event for the purpose of rating.

After implementation:

13. What will be the impact in the books of the investor?

In case of securitisation, the income will be booked by the investor as per the revised payout structure. In case of direct assignment, the assignee shall take the impact of restructuring in its books. Say, in case there is a reduction in interest rate, the asset must be booked at such revised interest rate in the books.

14. What will be the impact on asset classification and provisioning for such loans?

In case of moratorium, the asset classification will be on a standstill for the period for which moratorium is granted. After the moratorium period is over, the asset classification as per IRAC norms shall be applied. Further, as per the RBI guidelines for moratorium[3], additional provisions shall be required to be maintained.

In case of restructuring, the asset classification shall be on the revised loan, as per the IRAC norms.

15. Who will be required to maintain additional provisions?

Usually, investors maintain provisions corresponding to the PTCs held by them. The asset classficiation and provisioning is done on the basis of payout from such PTCs. Similarly, any additional provision that is required to be maintained, shall be maintained by the investor corresponding to the value of PTCs held.

Further, in the case of DA,both the assignee and assignor shall maintain the provisions, in their respective share of interest in the loan.

16. Suppose, after restructuring, the borrowers still fails to pay as per the restructured terms, what will be the impact on the rating?

In case the borrower fails to repay as per the restructured terms, it is a case of default beyond the moratorium/restructuring allowed by the RBI. This would result in a downgrade in the quality of the underlying asset. Hence, it is quite probable that the rating of the transaction may downgrade.

17. In case there is a rating downgrade, can the size of classes/tranches be changed?

The prime motivation for tranching a securitisation transaction is to obtain high rating for atleast a part of the transaction. Hence, the upper class, say class A, gets the maximum amount of credit support and is sized in a manner that it is able to get superior rating.

Now, when there is a threat of rating downgrade, the size of classes/tranches cannot be changed to maintain the rating. It is crucial to consider that the rating is allotted based on the structure of the transaction and not the other way round.

Hence, if at all, the originator intends to maintain the rating to the transaction, it may introduce further credit support to the transaction, but the size of classes should not be changed.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

[1] Refer our write-up on http://vinodkothari.com/2020/05/guaranteed-emergency-line-of-credit-understanding-and-faqs/

[2] https://www.sebi.gov.in/legal/circulars/mar-2020/-relaxation-from-compliance-with-certain-provisions-of-the-circulars-issued-under-sebi-credit-rating-agencies-regulations-1999-due-to-the-covid-19-pandemic-and-moratorium-permitted-by-rbi-_46449.html

[3] Refer: https://www.rbi.org.in/Scripts/NotificationUser.aspx?Id=11872&Mode=0

Stop crazy lending, lazy lending, write Rajan and Acharya

/0 Comments/in Financial Services, RBI /by Vinod Kothari Consultants– Vinod Kothari

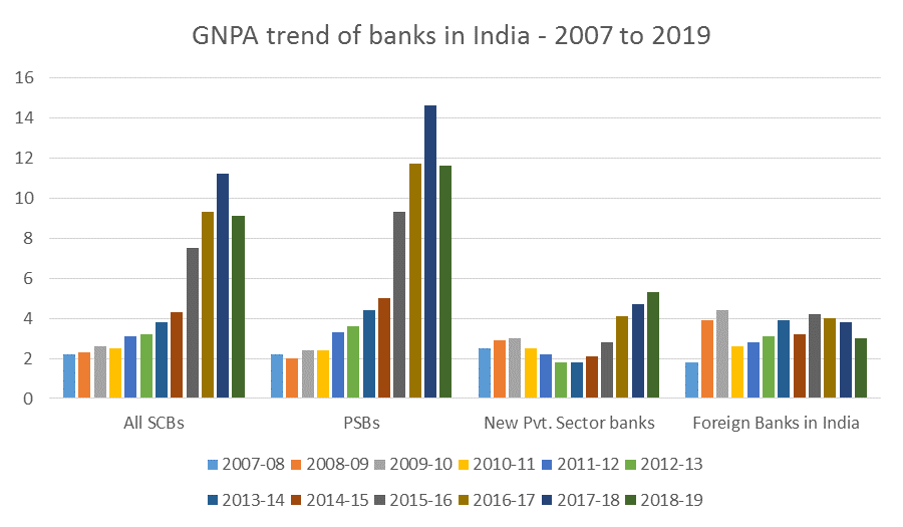

Raghuram Rajan and Viral Acharya, both having got the first-hand experience of holding the reins at the RBI, have prescribed several urgent measures to restore the health of the banking system. Neither do we have the fiscal space to support the banking system with fresh doses of capital, nor can we afford any more spikes in the almost top-of-the-world GNPA ratios. The duo, who have written several articles in the past, wrote this piece[1] on 21st Sept. 2020.

In a strongly worded write-up, the two celebrated academics of the financial world, have clearly taken it out on the bureaucracy and the government. The authors say while advocacy for comprehensive banking sector reforms have been done in the past, the onus of not making it happen is clearly on the government itself: “There are strong interests against change, which is why many would-be reformers are cynical, and either have given up, or recommend revolutionary change that has little chance of being implemented. We are more optimistic that a middle road is achievable, given that the greatest stumbling block has been the government, the bureaucracy, and the interests within it. With the enormous strains on government finances from the slow growth pre-COVID and the subsequent effects of the pandemic, the country has to transform the banking

sector from being a drain on government resources and an impediment to growth to becoming an engine of growth. This will not happen through incremental reforms. The status quo is fiscally untenable.”

The authors are unsparing when they clearly say the Department of Financial Services should be scrapped. The authors recommend that “Winding down Department of Financial Services in the Ministry of Finance is essential, both as an affirmative signal of the intent to grant bank boards and management independence and as a commitment not to engage in “mission creep” when compulsions arise to use banks for serving costly social or political objectives.” They also say that despite clear recommendations of the Nayak Committee in 2014[2], nothing has changed in terms of autonomy of the banks in the country. The authors may be resonating the bitterness of many senior bankers when they say: “Parliamentarians of all parties are not immune to the lure of public sector banks – the banks are often asked to arrange the logistics for their fact-finding committee meetings in enjoyable locales across the country. And Finance Ministry bureaucrats are reluctant to let go of the power that allows a young joint secretary to order the chairpersons of national banks around”

No more crazy lending, lazy lending

Banks in India cannot afford to have the false sense of having safe assets by “lazy lending”. The term, coined by Dr Rakesh Mohan, the-then Deputy Governor of RBI[3], refers to bankers choosing to invest in risk-free government bonds, even when the opportunity cost of capital for them is much higher. At the same time, banks also cannot afford to do “crazy lending”, by lending to riskiest of borrowers as more credit-worthy borrowers choose to rely on capital markets, and thereby, pile up non-performing loans on their balance sheets.

Indian banks, particularly PSUs, have managed to pile up bad loans on their balance sheet. There were sizeable NPAs even before the Covid. Six months of covid-moratorium meant virtually no cashflows, and as the servicing burden on the borrowers has increased over these months, most banks will be forced to use the loan restructuring option following covid-disruption[4]. The contention that the covid-disruption will become the alibi to restructure loans that were even otherwise fragile does not require much evidencing.

Source: Handbook of statistics on the Indian Economy, 2019-20[5]

Rajan and Acharya refer to the well-known ever-greening problem of Indian banking – with the bankers supporting bad loans by sequential doses of further lending, and the promoters continuously stripping the assets out and diverting profits and cashflows, leaving the borrower to be a “zombie”. Authors say that banks, by keeping the zombies alive, do a double damage to the system – on one hand, the bankers continue to focus on bad loan management and therefore, spend less time and resources to creating healthy loans, and on the other, the presence of half-dead firms discourages healthy industries as well.

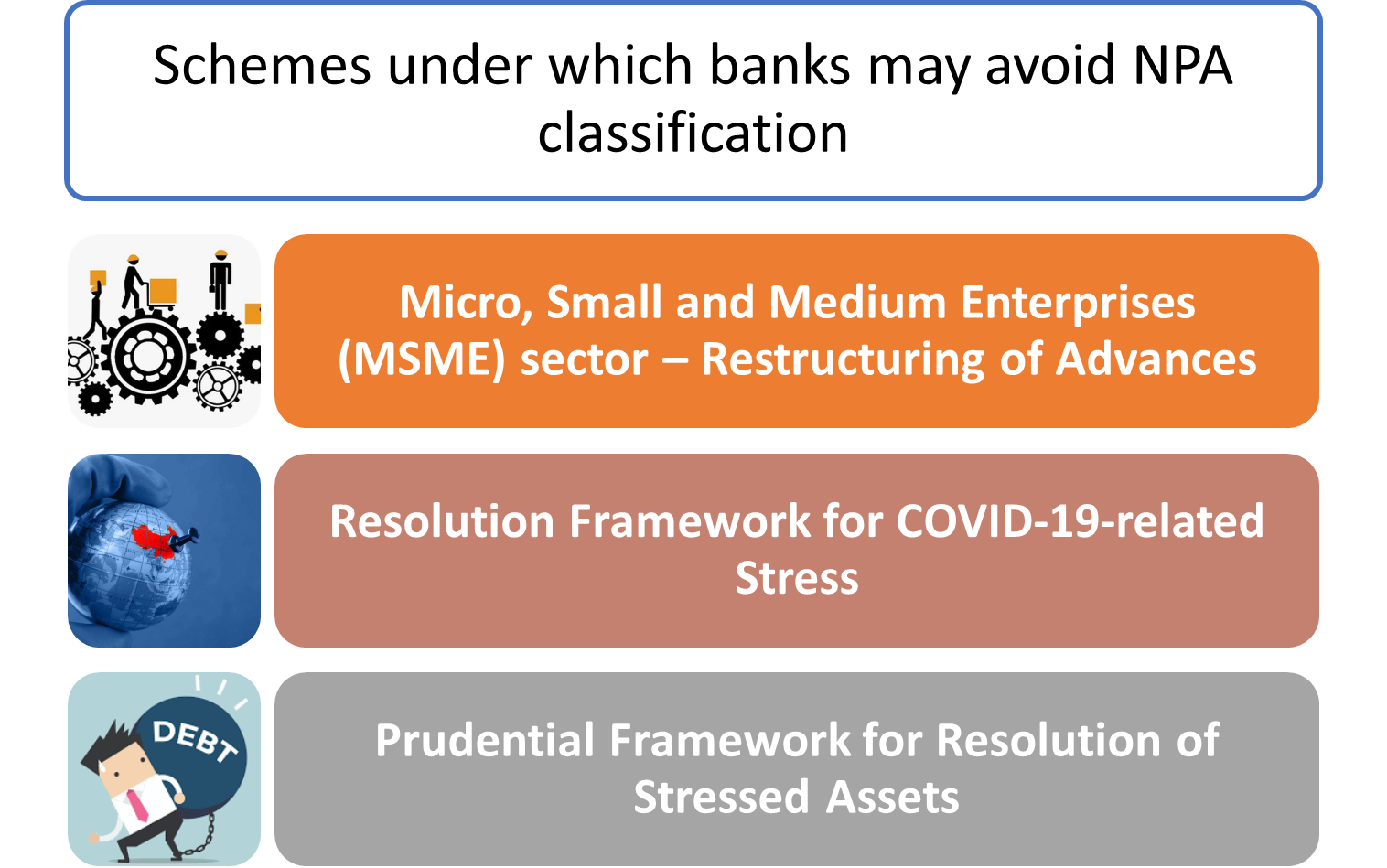

While banks over the world have converged to IFRS, which provides for an “expected loss” model, the Indian banking system is still driven by the regulatory requirement of provisioning, in form of the so-called IRAC (Income recognition and asset classification) norms. However, periodically, the RBI comes with schemes whereby banks can avoid classifying a loan as an NPA.

“With forbearance in the form of delayed provisioning, not only does the firm’s condition deteriorate, but the banker has to take a large loss when he eventually restructures the loan. So instead the banker holds off, under-provisioning mounts, and what was meant to be temporary regulatory forbearance inevitably creates banker demand for more, near-permanent forbearance”, say the authors. The authors say that fear-struck bankers are more comfortable in letting the NCLT process take over the bankers’ resolution, since, in that case, the decisions are made by the NCLT-appointed professional, and not by the bank, who may thus get sheltered by the proverbial 3 Cs that haunt bankers.

Arguing for the need to revisit sec. 29A of the Insolvency Code, Rajan and Acharya say that the provision are needed at the time when the defaulting borrower was to be prevented from buying bank his own assets and potentially scaring other buyers. But in the present scenario of pandemic stress, this will also prevent the promoter whose business faltered for no fault of his. The authors also reflect the reality when the say the NCLT “already has a large backlog of cases, some of which have dragged on for much longer than the targeted duration for bankruptcy. It cannot possibly handle the volume of distress that will have to be dealt with post-pandemic without a significant expansion of the number of its judges and benches. Unfortunately, the quantum of trained personnel that is needed may simply not exist.”

The authors also advocate the retention of the debtors’ control, at least in the post-pandemic restructurings. Notably, the creditors’ in control model that India has adopted, is inspired by the UK approach, whereas the USA has a debtor-in-control approach.

The authors are also in favour of a larger predominance of out-of-court resolutions: “Ideally though, there should be greater use of out-of-court restructuring and the NCLT should be used to stamp the out-of-court restructuring with legal finality. Only if an out-of-court restructuring could not be agreed upon between the creditors and the borrower would the firm be forced into a bankruptcy auction. The shadow of bankruptcy would then improve the ease and quality of the negotiation out of bankruptcy, as it does in other countries. But this requires bankers, especially public sector bankers, to be able to negotiate”

Creation of “bad bank”

The bad bank experience has had a limited success in India. IDBI created SASF in 2004. However, neither did it help the bad loans, nor IDBI. Subsequently, India has worked on a private sector model of so-called “bad banks”, in form of the ARCs. However, the transfer of loans to ARCs may mostly take the form of security receipts, which is paper-for-paper. It is only in the recent past that banks have insisted on all-cash loan transfers.

Hence, authors argue that what may be more effective is a transparent market for bad loans. Notably, the draft Directions for Sale of Loans, issued by the RBI for public comments on 08th June, 2020[6], provided, among other things, an auction-based disposal of bad loans. There is apparently also a discussion on permitting foreign investors to invest in bad loans directly.

Additionally, the authors also suggest the creation of a “public credit registry”. Currently, there are multiple registries in India working with significant overlaps and lack of cohesiveness. CERSAI, NeSL, and CRILC are such registries, each intended to serve different purposes. However, it will not be a high hanging fruit to combine them into a loan registry, where the information about a loan, its collateral, performance, etc. are all pooled into a single database. Authors say that KAMCO, Korea, after completion of its asset management task, is now evolving itself into a loan registry.

Authors suggest that selling of loans will bring transparency and price discovery. Currently, RBI’s regulatory framework has been restraining banks from selling loans, mainly on the concerns of originate-to-hold model.

The authors contend that if a transparent pricing could emerge by creating a secondary market, a bad bank could emerge by the market mechanism itself. These market-based bad banks can have sectoral focus, rather than a generic pool of NPAs as is currently the case. The authors also cite global examples of warehousing bad loans to find a more opportune time for disposing them.

Move from asset-based lending to cashflow-based lending

Lending can be, as it traditionally has been, focused on the on-balance sheet assets and collateral, or may be focused on the cashflows of the business. In case of asset-based lending, the lender focuses on balance sheet ratios such as leverage and loan-to-value. In cash-flow based lending approach, the lender focuses on liquidity and debt-servicing ability.

An RBI Expert Group led by Shri U K Sinha recommended a cash-flow based lending structure for MSME funding[7].

Recently, large Indian banks announced plans to move to cashflow-based lending, such as SBI. SBI Chairman Rajnish Kumar stated “SBI will switch to a cash flow-based lending model beginning April 2020 from a mechanism where loans are given against assets”[8].

The authors have recommended a transition from asset based lending to (also) cash flow based lending. The authors mention that “Banks could rely more on loan covenants for large borrowers, tied to liquidity and leverage ratios (instead of lending purely against assets). This would set up “trip wire” points for enhancing loan collateralization, rather than requiring it from the beginning; in case of small borrowers, reliance on GST invoices and utility payment bills, among other cashflow information, can facilitate such a transition.”

Group-lending limits

The authors talk about the problem relating to certain promoters running large conglomerates while sitting on thin slices of equity. Due to this the following problems are highlighted by the authors, namely, a) this creates systemic risk in the banking system, b) leads to concentration of corporate power and a complex maze of related party transactions between financial and real subsidiaries of the group that are often the veil behind which frauds are perpetrated.

The authors recommend that highly indebted groups should not be allowed to expand their footprint significantly by using bank money to bid on new projects. Group lending norms should be enforced as the economy recovers. Further, the authors state that aggregate permissible system exposures should be linked to the aggregate debt equity ratio for the group (including non-bank borrowing and foreign borrowing). Over-leveraging by specific promoters or groups needs to be limited if the Indian banking system’s health is to be restored.

[1] https://faculty.chicagobooth.edu/-/media/faculty/raghuram-rajan/research/papers/paper-on-banking-sector-reforms-rr-va-final.pdf

[2] https://rbidocs.rbi.org.in/rdocs/PublicationReport/Pdfs/BCF090514FR.pdf

[3] https://www.rbi.org.in/scripts/BS_SpeechesView.aspx?Id=310

[4] https://www.rbi.org.in/Scripts/NotificationUser.aspx?Id=11941&Mode=0

Our write up & FAQs on the framework may be viewed here: http://vinodkothari.com/2020/08/resolution-framework-for-covid-19-related-stress-resfracors/

http://vinodkothari.com/2020/09/faqs-on-resolution-of-loan-accounts-under-covid-19-stress/

[5] https://rbidocs.rbi.org.in/rdocs/Publications/PDFs/58TB5A66F26A72F460687373406F1D51C43.PDF

[6] https://www.rbi.org.in/Scripts/PublicationReportDetails.aspx?UrlPage=&ID=957

[7] https://www.rbi.org.in/Scripts/PublicationReportDetails.aspx?UrlPage=&ID=924

[8] https://www.financialexpress.com/industry/banking-finance/sbi-to-shift-to-cash-flow-based-lending-by-april-2020/1797095/

RBI refines the role of the Compliance-Man of a Bank

/0 Comments/in Banking Regulations, Financial Services, RBI /by Vinod Kothari ConsultantsNotifies new provisions relating to Compliance Functions in Banks and lays down Role of CCO.

By:

Shaivi Bhamaria | Associate

Aanchal Kaur Nagpal | Executive

Introduction

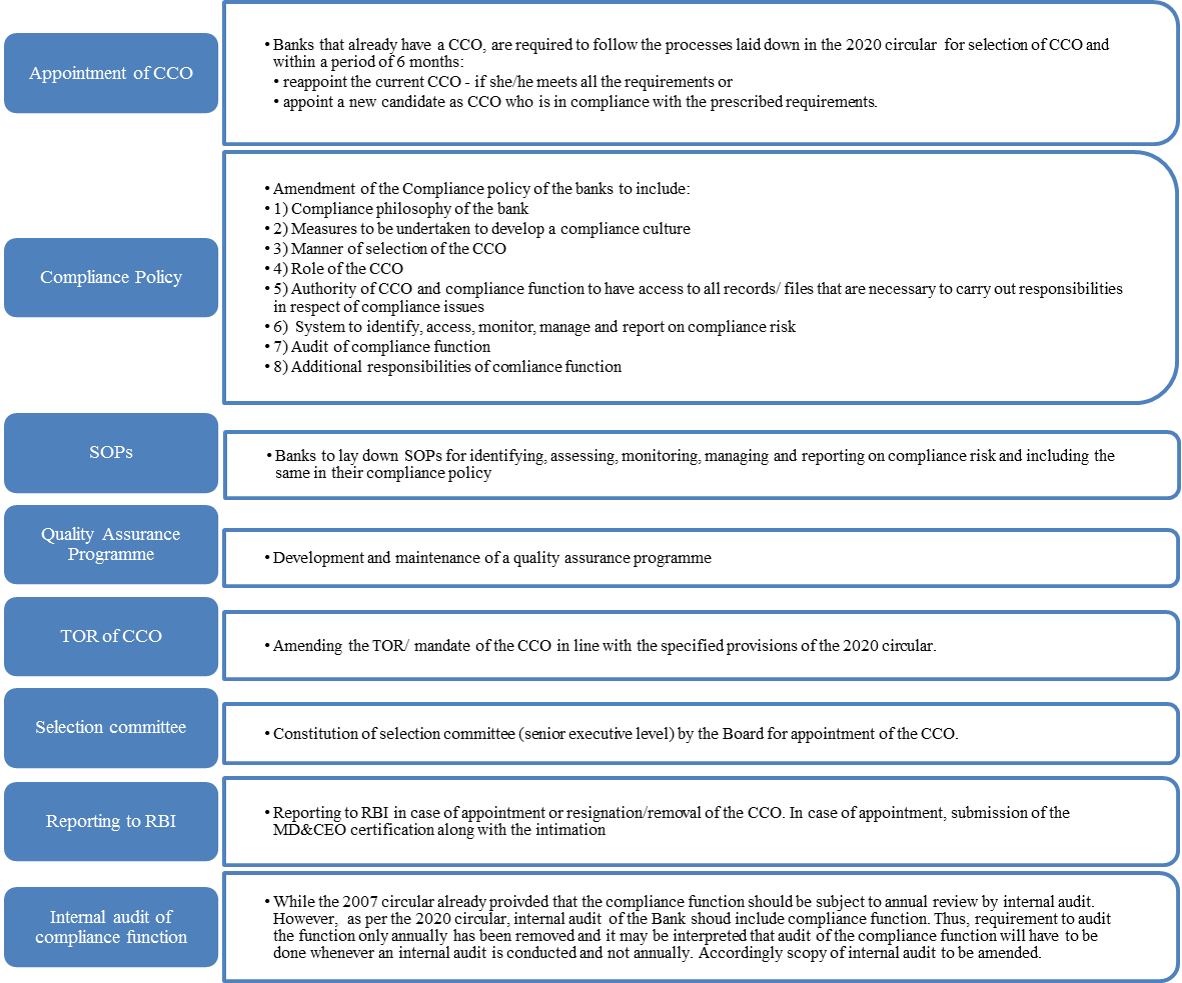

The recent debacles in banking/shadow banking sector have led to regulatory concerns, which are reflected in recent moves of the RBI. While development of a robust “compliance culture” has always been a point of emphasis, RBI in its Discussion Paper on “Governance in Commercial Banks in India’[1] [‘Governance Paper’] dated 11th June 2020 has dealt extensively with the essentials of compliance function in banks. The Governance Paper, while referring to extant norms pertaining to the compliance function in banks, viz. RBI circulars on compliance function issued in 2007[2] [‘2007 circular’] and 2015[3] [‘2015 circular’], placed certain improvement points.

In furtherance of the above, RBI has come up with a circular on ‘Compliance functions in banks and Role of Chief Compliance Officer’ [‘2020 Circular’] dated 11th September, 2020[4], these new guidelines are supplementary to the 2007 and 2015 circulars and have to be read in conformity with the same. However, in case of or any common areas of guidance, the new circular must be followed. Along with defining the role of the Chief Compliance Officer [‘CCO’], they also introduce additional provisions to be included in the compliance policy of the Bank in an effort to broaden and streamline the processes used in the compliance function.

Generally, in compliance function is seen as being limited to laying down statutory norms, however, the importance of an effective compliance function is not unknown. The same becomes all-the-more paramount in case of banks considering the critical role they play in public interest and in the economy at large. For a robust compliance system in Banks, an independent and efficient compliance function becomes almost indispensable. The effectiveness of such a compliance function is directly attributable to the CCO of the Bank.

Need for the circular

The compliance function in banks is monitored by guidelines specified by the 2007 and 2015 circular. These guidelines are consistent with the report issued by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS Report)[5] in April, 2005.

While these guidelines specify a number of functions to be performed by the CCO, no specific instructions for his appointment have been specified. This led to banks following varied practices according to their own tailor-made standards thus defeating the entire purpose of a CCO. Owing to this, RBI has vide the 2020 circular issued guidelines on the role of a CCO, in order to bring uniformity and to do justice to the appointment of a CCO in a bank.

Background of CCOs

The designation of a CCO was first introduced by RBI in August, 1992 in accordance with the recommendations of the Ghosh Committee on Frauds and Malpractices in Banks. After almost 15 years, RBI introduced elaborate guidelines on compliance function and compliance officer in the form of the 2007 circular which was in line with the BCBS report.

According to the BCBS report:

‘Each bank should have an executive or senior staff member with overall responsibility for co-ordinating the identification and management of the bank’s compliance risk and for supervising the activities of other compliance function staff. This paper uses the title “head of compliance” to describe this position’.

Who is a CCO and how is he different from other compliance officials?

The requirement of an individual overseeing regulatory compliance is not unique to the banking sector. There are various other laws that the provide for the appointment of a compliance officer. However, there is a significant difference in the role which a CCO is expected to play. The domain of CCO is not limited to any particular law or its ancillaries, rather, it is all pervasive. He is not only responsible for heading the compliance function, but also overseeing the entire compliance risk[6] in banks.

Role of a CCO in a Bank:

The predominant role of a CCO is to head the compliance function in a Bank. The 2007 circular lays down the following mandate of a CCO:

- overall responsibility for coordinating the identification and management of the bank’s compliance risk and supervising the activities of other compliance function staff.

- assisting the top management in managing effectively the compliance risks faced by the bank.

- nodal point of contact between the bank and the RBI

- approving compliance manuals for various functions in a bank

- report findings of investigation of various departments of the bank such as at frequent intervals,

- participate in the quarterly informal discussions held with RBI.

- putting up a monthly report on the position of compliance risk to the senior management/CEO.

- the audit function should keep the Head of compliance informed of audit findings related to compliance.

The 2020 circular adds additional the following responsibilities on the CCO:

- Design and maintenance of compliance framework,

- Training on regulatory and conduct risks,

- Effective communication of compliance expectations

Selection and Appointment of CCO:

The 2007 circular is ambiguous on the qualifications, roles and responsibilities of the CCO. In certain places the CCO was referred to as the Chief Compliance officer and some places where the words compliance officer is used. This led to difficulty in the interpretation of aspects revolving around a CCO. However, the new circular gives a clear picture of the expectation of RBI from banks in respect of a CCO. The same has been listed below:

| Basis | 2020 circular | 2007 circular |

| Tenure | Minimum fixed tenure of not less than 3 years | The Compliance Officer should be appointed for a fixed tenure |

| Eligibility Criteria for appointment as CCO | The CCO should be the senior executive of the bank, preferably in the rank of a General Manager or an equivalent position (not below two levels from the CEO). | The compliance department should have an executive or senior staff member of the cadre not less than in the rank of DGM or equivalent designated as Group Compliance Officer or Head of Compliance. |

| Age | 55 years | No provision |

| Experience | Overall experience of at least 15 years in the banking or financial services, out of which minimum 5 years shall be in the Audit / Finance / Compliance / Legal / Risk Management functions. | No provision

|

| Skills | Good understanding of industry and risk management, knowledge of regulations, legal framework and sensitivity to supervisors’ expectations | No provision |

| Stature | The CCO shall have the ability to independently exercise judgement. He should have the freedom and sufficient authority to interact with regulators/supervisors directly and ensure compliance | No provision |

| Additional condition | No vigilance case or adverse observation from RBI, shall be pending against the candidate identified for appointment as the CCO. | No provision |

| Selection* | 1. A well-defined selection process to be established

2. The Board must be required to constitute a selection committee consisting of senior executives 3. The CCO shall be appointed based on the recommendations of the selection committee. 4. The selection committee must recommend the names of candidates suitable for the post as per the rank in order of merit. 5. Board to take final decision in the appointment of the CCO. |

No provision |

| Review of performance appraisal | The performance appraisal of the CCO should be reviewed by the Board/ACB | No provision |

| Reporting lines | The CCO will have direct reporting lines to the following:

1. MD & CEO and/or 2. Board or Audit Committee |

No provision |

| Additional reporting | In case the CCO reports to the MD & CEO, the Audit Committee of the Board is required to meet the CCO quarterly on one-to-one basis, without the presence of the senior management including MD & CEO. | No provision |

| Reporting to RBI | 1. Prior intimation is to be given to the RBI in case of appointment, premature transfer/removal of the CCO.

2. A detailed profile of the candidate along with the fit and proper certification by the MD & CEO of the bank to be submitted along with the intimation, confirming that the person meets the supervisory requirements, and detailed rationale for changes. |

No provision |

| Prohibitions on the CCO | 1. Prohibition on having reporting relationship with business verticals

2. Prohibition on giving business targets to CCO 3. Prohibition to become a member of any committee which brings the role of a CCO in conflict with responsibility as member of the committee. Further, the CCO cannot be a member of any committee dealing with purchases / sanctions. In case the CCO is member of such committees, he may play only an advisory role. |

No provision |

*The Governance paper had proposed that the Risk Management Committee of the Board will be responsible for selection, oversight of performance including performance appraisals and dismissal of a CCO. Further, any premature removal of the CCO will require with prior board approval. [Para 9(6)] However, the 2020 circular goes one step further by requiring a selection committee for selection of a CCO.

Dual Hatting

Prohibition of dual hatting is already applicable on the Chief Risk Officer (‘CRO’) of a bank. The same has also been implemented in case the of a CCO.

Hence, the CCO cannot be given any responsibility which gives rise to any conflict of interest, especially the role relating to business. However, roles where there is no direct conflict of interest for instance, anti-money laundering officer, etc. can be performed by the CCO. In such cases, the principle of proportionality in terms of bank’s size, complexity, risk management strategy and structures should justify such dual role. [para 2.11 of the 2020 circular]

Role of the Board in the Compliance function

Role of the Board

The bank’s Board of Directors are overall responsible for overseeing the effective management of the bank’s compliance function and compliance risk.

Role of MD & CEO

The MD & CEO is required to ensure the presence of independent compliance function and adherence to the compliance policy of the bank.

Authority:

The CCO and compliance function shall have the authority to communicate with any staff member and have access to all records or files that are necessary to enable him/her to carry out entrusted responsibilities in respect of compliance issues.

Compliance policy and its contents

The 2007 circular required banks to formulate a Compliance Policy, outlining the role and set up of the Compliance Department.

The 2020 circular has laid down additional points that must be covered by the Compliance Policy. In some aspects, the 2020 circular provides further measures to be taken by banks whereas in some aspects, fresh points have been introduced to be covered in the compliance policy, these have been highlighted below:

1. Compliance philosophy: The policy must highlight the compliance philosophy and expectations on compliance culture covering:

- tone from the top,

- accountability,

- incentive structure

- Effective communication and Challenges thereof

2. Structure of the compliance function: The structure and role of the compliance function and the role of CCO must be laid down in the policy

3. Management of compliance risk: The policy should lay down the processes for identifying, assessing, monitoring, managing and reporting on compliance risk throughout the bank.

The same should adequately reflect the size, complexity and compliance risk profile of the bank, expectations on ensuring compliance to all applicable statutory provisions, rules and regulations, various codes of conducts and the bank’s own internal rules, policies and procedures and must create a disincentive structure for compliance breaches.

4. Focus Areas: The policy should lay special thrust on:

- building up compliance culture;

- vetting of the quality of supervisory / regulatory compliance reports to RBI by the top executives, non-executive Chairman / Chairman and ACB of the bank, as the case may be.

5. Review of the policy: The policy should be reviewed at least once a year

Quality assurance of compliance function

Vide the 2020 circular, RBI has introduced the concept of quality assurance of the compliance function Banks are required to develop and maintain a quality assurance and improvement program covering all aspects of the compliance function.

The quality assurance and improvement program should be subject to independent external review at least once in 3 years. Banks must include in their Compliance Policy provisions relating to quality assurance.

Thus, this would ensure that the compliance function of a bank is not just a bunch of mundane and outdated systems but is improved and updated according to the dynamic nature of the regulatory environment of a bank.

Responsibilities of the compliance function

In addition to the role of the compliance function under the compliance process and procedure as laid down in the 2007 the 2020 circular has laid down the below mentioned duties and responsibilities of the compliance function:

- To apprise the Board and senior management on regulations, rules and standards and any further developments.

- To provide clarification on any compliance related issues.

- To conduct assessment of the compliance risk (at least once a year) and to develop a risk-oriented activity plan for compliance assessment. The activity plan should be submitted to the ACB for approval and be made available to the internal audit.

- To report promptly to the Board/ Audit Committee/ MD & CEO about any major changes / observations relating to the compliance risk.

- To periodically report on compliance failures/breaches to the Board/ACB and circulating to the concerned functional heads.

- To monitor and periodically test compliance by performing sufficient and representative compliance testing. The results of the compliance testing should be placed before the Board/Audit Committee/MD & CEO.

- To examine sustenance of compliance as an integral part of compliance testing and annual compliance assessment exercise.

- To ensure compliance of Supervisory observations made by RBI and/or any other directions in both letter and spirit in a time bound and sustainable manner.

Actionables by Banks:

Links to related write ups –

- RBI proposes to strengthen governance in banks

- RBI proposes to consolidate guidelines on governance for commercial banks

- RBI guidelines on governance in commercial banks

[1] https://www.rbi.org.in/Scripts/BS_PressReleaseDisplay.aspx?prid=49937

[2] https://www.rbi.org.in/Scripts/NotificationUser.aspx?Id=3433&Mode=0

[3] https://www.rbi.org.in/Scripts/NotificationUser.aspx?Id=9598&Mode=0

[4] https://www.rbi.org.in/Scripts/NotificationUser.aspx?Id=11962&Mode=0

[5] https://www.bis.org/publ/bcbs113.pdf

[6] According to BCBS report, compliance risk is the risk of legal or regulatory sanctions, material financial loss, or loss to reputation a bank may suffer as a result of its failure to comply with laws, regulations, rules, related self-regulatory organization standards, and codes of conduct applicable to its banking activities”

Moratorium Scheme: Conundrum of Interest on Interest

/0 Comments/in Financial Services, RBI /by Vinod Kothari ConsultantsSiddhart Goel

Introduction

On September 03, 2020 the Hon’ble Supreme Court (the “court”) while dealing with several petitions on account of Covid related stress from various stakeholders, passed an interim order that that the accounts which have not declared NPA till August 31, 2020 shall not be declared NPA till further orders of the court.[1] Further in its September 10, 2020 order the court asked the government and RBI to file affidavit within two weeks to the court, on issues raised and relief granted thereto.[2]

The primary contention raised before the court for consideration was that the moratorium postpones the burden and does not eases the plight. It would be a double whammy on borrowers since Banks are charging compounded interest, and banks have benefitted during moratorium by charging compounded interest from customers. The court in its order dated September 10, 2020 observed that individuals are more adversely affected during this period of pandemic. Therefore, the court from the government and RBI, with regard to charging of compound interest and credit rating/downgrading during moratorium period, has sought specific instructions.

Though the matter is sub judice, this write-up aims to provide a legal analyses to the contentions raised in front of the court on the above counts, since any action or direction on the above issues will have an impact on the wider financial system including all, i.e. borrowers, government, banks and other financial institutions as a whole.

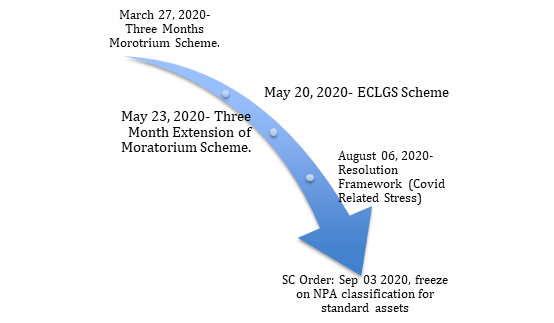

Before directly getting into the analyses, it is important to consider material reliefs and incentives announced by RBI and Government of India in respect to COVID19 related regulatory package. A brief history of timelines on series of regulatory reforms to cope with the disruptions caused due to COVID19 is provided below:

Waiver of Interest on Interest during moratorium and Systemic Implications

The moratorium scheme deferred the repayment schedule for loans, and the residual tenor, was to be shifted across the board. This essentially meant that all the liabilities of customers towards their repayments (principal plus interests) were to be rescheduled and shifted across the board by the Banks and NBFCs. However, the scheme clearly stipulated that the interest should continue to accrue on the outstanding portion of the term loans during the moratorium period. Moratorium granted to the customers of banks and NBFCs was to reprieve borrowers from any immediate liability to pay. However, charging of interest on outstanding accrued amount is the center of concern in the matter.

The money has time value, which is often expressed as interest in banking parlance. This is one of the most fundamental principles in finance. Rupee 1 today is more valuable from a year today. If interest is not paid, when it accrues, this in effect means, right to receive interest, which is a predictable stream of cash flow, is not available for reinvestment. Therefore, interest earned but not paid, should earn interest until paid. In debt markets, an obligation towards debt is valued in reference to yield to maturity or present value, all these rest on the compounding interest. These are generally in form of obligations on Banks and NBFCs on the liability side of their balance sheet. Bank deposits and interest thereon also attracts interest, which is adjusted towards total deposit amount of the customer. Therefore, interest on interest is a rule in finance and not a selective event.

Banking is no different to any other commercial business, besides it involves liquidity and maturity transformation and hence is highly leveraged. The short-term demand deposits from customers are converted into long-term loans to borrowers (‘maturity transformation’). Similarly, the customer deposits (liabilities of banks) are payable on demand, while on asset side receivables (repayment of principal and interest) are fixed on due dates (‘liquidity transformation’). It would be wrong to presume that NBFCs are any different from commercial banks. NBFCs largely rely on borrowings from Banks and other financial institutions by way of issuing debt instruments (CP, bonds, etc.), which is reflected on the asset side of the investing commercial banks and other financial institutions. Though obligation of payment on these debt instruments is not payable on demand, but they carry a substantial roll over and default risk. Hence, these institutions are highly leveraged and inherently fragile by nature of their business. Needless to state that receivables on asset side of banks and NBFC also carry certain risk of default and therefore are inherently risky in nature.

Financial institutions and other investors in market, (like Money Market Funds, Pension funds and etc.) invest in debt of Banks and NBFCs on the basis of strength of assets held by them. These assets are in form of receivables from pool of loans or by way advances to underlying borrowers. Thus, participants in financial markets are highly interlinked and are adversely affected by asset deterioration as a rule. Banks and financial institutions bear credit risk (default risk) of the underlying borrowers on their balance sheet. This credit risk has already increased substantially and would be unfolding further due the impact of pandemic on wider economy.

The waiver of interest charged on interest accrued but not paid during the moratorium, would not only be a loss for the banks and NBFCs, but would also substantially dilute the value of assets held by them. This could lead to an asset liability mismatch on balance sheets of banks. Such waiver of interest on accrued amount could exacerbate the risk of banks and NBFCs defaulting on other financial institutions (‘systemic risk’). The foregoing of charging of interest on interest accrued during moratorium would mean banks and financial institutions partially baling out borrowers either from their own limited funds or from the borrowed funds of other financial institutions. Such a move could entail systemic risk and wider financial catastrophe. As risk of default from comparatively large diversified group of borrowers will be shifted and get concentrated in the balance sheets of banks and financial institutions.

Credit Rating Downgrades and Stressed Assets Resolution

The RBI moratorium notification dated March 27, 2020, freezes the delinquency status of the loan accounts, which have availed moratorium benefit under the scheme. This essentially meant that asset classification standstill will be imposed for accounts where the benefit of moratorium have been extended.[3] As it stands, the RBI, March 27, 2020 circular clearly stipulated that moratorium/deferment/recalculation of loans is provided to borrowers to tide over economic fallout due to COVID and same shall not be treated as concession or change in terms and conditions due to financial difficulty of the borrower. In essence the rescheduling of payments and interest is not a default and should not be reported to Credit Information Companies (CICs). A counter obligation on CIC was also imposed to ensure credit history of the borrowers is not impacted negatively, which are availing benefits under the scheme. The relevant excerpt from the notification stipulates as follows:

“7. The rescheduling of payments, including interest, will not qualify as a default for the purposes of supervisory reporting and reporting to Credit Information Companies (CICs) by the lending institutions. CICs shall ensure that the actions taken by lending institutions pursuant to the above announcements do not adversely impact the credit history of the beneficiaries.”

Further through notifications dated August 06, 2020 RBI introduced a special window scheme for Resolution of stress on account of COVID 19 (“Special Window”). Banks and financial institutions could restructure the eligible accounts under the Special Window without any asset classification downgrade of borrowers. The Special Window scheme included personal loans to individuals and other corporate exposures. It is relevant to realize that the resolution of stressed assets is highly subjective to borrower’s leverage, sector specific risks, and other financial parameters. Banks and Financial institutions are better placed to implement the resolution or restructuring of the assets (loan accounts) at bank level.

The moratorium scheme and the Special Window resolution framework dated August 06, 2020 (the “Schemes”) were highlights of discussions during the court proceedings extensively. The primary contentions were in respect to limited applicability of these schemes. The schemes and their benefits were available to borrowers whose accounts were standard and not more than 30 DPD as on March 01, 2020 with their respective banks and financial institutions. Though the legal validity of the schemes were questioned directly in front of the court, but selective nature of schemes conferring benefit on to standard accounts (which are not more than 30 DPDs) only. The exclusion of other borrower accounts was criticised extensively. But this could form as a part of separate issue, the primary concern here being asset down gradation and credit rating scores.

The Special Window restructuring scheme notification under its disclosures and credit reporting section made an onus on lending institutions to make disclosures on such re-structured assets in their annual financial statements along with other disclosures. However where accounts have been restructured under special facility, and involve ‘renegotiations’, it shall qualify as restructuring and the same shall be governed under credit information polices as applicable. The relevant clause is produced as is herein below:

“54. The credit reporting by the lending institutions in respect of borrowers where the resolution plan is implemented under this facility shall reflect the “restructured” status of the account if the resolution plan involves renegotiations that would be classified as restructuring under the Prudential Framework. The credit history of the borrowers shall consequently be governed by the respective policies of the credit information companies as applicable to accounts that are restructured.”

It is argued that the area of application and scope of both the schemes are entirely exclusive and independent remedies available to respective eligible borrowers. Under moratorium scheme the borrower gets benefit of liquidity since all the payments due during the period are deferred. While in the latter, i.e. restructuring scheme the borrower under stress can get their accounts restructured by way of implementing resolution plan without facing any asset classification downgrade upfront. In the latter case, only such restructurings involving ‘renegotiations’ will affect the credit history of the borrowers.

Conclusion

The intention of the RBI and the government was to provide relief to the borrowers, who were gasping for relief after the disruptions caused due to COVID 19. There is no doubt that the COVID-19 outbreak and subsequent lockdown has impacted all level of borrowers, ranging from small to large borrowers, including, individuals to corporates. It would be wrong to presume that those accounts, which were NPA or otherwise ineligible under the schemes, are not affected by the pandemic. Therefore it is always open for the government and RBI to introduce or implement any other scheme or some sort of reprieving mechanism for the ineligible borrowers. However, it is important to consider that even banks and financial institutions are no exception like any other businesses that have been affected by the pandemic; moreover they have been exposed to severe liquidity crunch and on the flip side are witnessing asset quality problems on their balance sheets. Any attempts to tamper or distort with the fundamental principle of finance (‘interest on interest’) or shifting the burden of it on banks and other financial institutions could have a much wider systemic ramifications than the current economic stress.

[1] https://main.sci.gov.in/supremecourt/2020/11127/11127_2020_34_16_23763_Order_03-Sep-2020.pdf

[2] https://main.sci.gov.in/supremecourt/2020/11127/11127_2020_36_1_23895_Order_10-Sep-2020.pdf

[3] Our detailed write up asset classification standstill is available at < http://vinodkothari.com/2020/04/the-great-lockdown-standstill-on-asset-classification/>

Udyam becomes mandatory: RBI clarifies Lenders’ stand

/2 Comments/in Financial Services, RBI /by Vinod Kothari Consultants-Kanakprabha Jethani and Anita Baid (finserv@vinodkothari.com)

Background

On June 26, 2020, the Ministry of Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MoM) released a notification[1] changing the definition of MSMEs and introducing a new process for MSME registration. The notification also stated that the existing MSME registrations (i.e. Udyog Aadhaar Number (UAN) or Enterprise Memorandum (EM)) shall be invalid after March 31, 2021. While the enterprises have to obtain Udyam Registration, the RBI has also made it mandatory for the lenders to ensure that their MSME borrowers have obtained the registration. The RBI through its notification dated August 21, 2020, has provided certain clarifications on its existing guidelines and stated clearly the things to be taken care of by the lenders. The following write-up intends to provide an understanding of the said clarifications and analyze them at the same time.

Udyam Registration to be the only valid proof

Under the existing framework for MSME registration, MSME borrowers had an option to provide either their Udyog Aadhaar Number (UAN), Entrepreneurs Memorandum (EM) or a proof of investment in plant and machinery or equipment being within the limits provided in the erstwhile definition along with a self-declaration of being eligible to be classified as an MSME. However, since the MoM notification stated that the UAN or EM shall be valid only till March 31, 2021, the MSMEs will have to compulsorily get registered under the Udyam portal, as per the revised definition. Hence, the lenders shall before March 31, 2021, obtain Udyam Registration proof from their existing as well as new borrowers.

In case of loans whose tenure shall end before March 31, 2021, the above requirement may not be relevant i.e. to obtain Udyam Registration since the existing registration submitted earlier by the borrowers shall be valid till the expiry of the loan tenure.

Pursuant aforesaid notifications, it seems that from March 31, 2021, Udyam Registration shall be the only valid proof for an entity to be recognized as an MSME. In such a case, it is pertinent to note that a notification issued by Ministry of MSMEs on July 17, 2020[2], which provides a list of activities that are not covered under Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises Development Act, 2006 (MSMED Act) for Udyam Registration. The list of activities is as follows:

- Forestry and logging

- Fishing and aquaculture