Archive for year: 2020

FDI Policy consolidated after 3 years: mismatches with NDI Rules remain

/0 Comments/in Corporate Laws, FEMA /by Vinod Kothari ConsultantsFEMA (Non-Debt Instruments) Rules, 2019 requires to be aligned for few sectors.

Bunny Sehgal | Associate | Vinod Kothari and Company

corplaw@vinodkothari.com

Introduction

The Department for Promotion of Industry and Internal Trade (‘DPIIT’) issued the Consolidated FDI Policy, 2020 (‘FDI Policy, 2020’) on October 28, 2020[1] in supersession of all press notes/ press release/ clarifications/ circulars issued by DPIIT. The FDI Policy, 2020, issued after 3 years[2], is effective from October 15, 2020. In case of any inconsistency or conflict between the provisions of FDI Policy 2020 and FEMA (Non-Debt Instruments) Rules, 2019 (‘NDI Rules’), the relevant provisions of the NDI Rules will prevail.

FDI Policy is generally a compilation/ consolidation of all press notes/ press releases/ clarifications/ circulars issued by the DPIIT. The author has compared the FDI Policy, 2020 with the erstwhile policy, NDI Rules, and press notes issued by DPIIT in order to ascertain if there is any new insertion in the FDI Policy, 2020 or if the provisions deviate from NDI Rules and discussed the changes in this article.

1. Definition of E-commerce entity

Under the NDI Rules, E-commerce entity means a company incorporated under Companies Act 1956, or the Companies Act, 2013.

However, under the FDI Policy, 2020, an E-commerce entity means the following:

- a company incorporated under Companies Act 1956, or the Companies Act, 2013;or

- foreign company under section 2 (42) of the Companies Act, 2013; or

- an office, branch or agency in India as provided in section 2 (v) (iii) of FEMA 1999, owned or controlled by a person resident outside India and conducting the e-commerce business.

The FDI Policy, 2020 elaborates the definition further to include foreign company and office, branch or agency in India owned or controlled by a person resident outside India. The changes have been brought in line with the definition of E-commerce entity provided in the Press Note 2 of 2018[3] issued by Department of Industrial Policy and Promotion effective from February 01, 2019.

2. FDI in Defence Sector

The provisions of the NDI Rules and the FDI Policy, 2020 with regard to the FDI sectoral cap and the necessary approvals for FDI in Defence Sector, have been provided as follows:

| Sr. No. | NDI Rules | FDI Policy, 2020 |

| 1. | Defence Industry subject to Industrial license under the Industries (Development & Regulation) Act, 1951 and Manufacturing of small arms and ammunition under the Arms Act, 1959 | |

Sectoral Cap- 100%

|

Sectoral Cap- 100%

|

|

| Other Conditions ( Relevant extract) | ||

| 2. |

|

|

The limits provided in the FDI Policy, 2020 and other conditions were proposed vide press note 4 of 2020[4], and it will take effect from the date of FEMA notification. The FEMA notification in this regard is awaited, therefore, the amendment is not effective as on date.

3. FDI in Private Security Agencies

The provisions of the NDI Rules and the FDI Policy, 2020 with regard to the FDI sectoral cap and the necessary approvals for FDI in Private Security Agencies, have been provided as follows:

| Sr. No. | NDI Rules | FDI Policy, 2020 |

| 1. | Sectoral Cap- Upto 49% through Government approval only. | Sectoral Cap- Upto 74%

|

The sectoral cap for FDI in Private Security Agencies was revised as per the aforesaid limits vide Press Note 5 of 2016[5] dated June 24, 2016 effective on immediate basis. However, the NDI Rules continue to refer to old limits. The same is required to be aligned with FDI Policy, 2020

4. FDI in Asset Reconstruction Companies

The FDI Policy, 2020 provides following additional conditions for making foreign investment in Asset Reconstruction Companies (ARCs) as prescribed in Press Note 4 of 2016[6] dated May 6, 2016 effective on immediate basis:

- A person resident outside India can invest in the capital of ARCs registered with Reserve Bank of India, up to 100% on the automatic route.

- The total shareholding of an individual FPI shall be below 10% of the total paid-up capital.

However, the NDI Rules do not provide for the aforesaid conditions in this regard. While (i) above is self-explanatory and that express provision will not make much difference, the condition given in (ii) is crucial.

Conclusion

The intent and objective of the Government of India is to attract and promote FDI in order to supplement domestic capital, technology and skills for accelerated economic growth and development. With the enforcement of FDI Policy, 2020, some gaps have been observed in the provisions of NDI Rules and FDI Policy, 2020 which have been left over either inadvertently, or due to pending notification of the same. Although, the FDI Policy, 2020 itself provides for the superiority of the NDI Rules in case of any conflict between the provisions of the FDI Policy, 2020, and the NDI Rules, it is imperative for the authorities to look into to bring the uniformity in the provisions.

Other relevant material of interest –

[1] https://dipp.gov.in/sites/default/files/FDI-PolicyCircular-2020-29October2020_0.pdf

[2] The former Consolidated FDI Policy was issued in 2017.

[3] https://dipp.gov.in/sites/default/files/pn2_2018.pdf

[4] https://dipp.gov.in/sites/default/files/pn4-2020_0.PDF

Secured Creditors under Insolvency Code : Searching for Equilibrium

/0 Comments/in Insolvency and Bankruptcy, Resolution /by Vinod Kothari ConsultantsThis article has been published in IBBI’s annual publication named Insolvency and Bankruptcy Board of India – A Narrative, (2020). See here

All about Electronic contracts

/0 Comments/in Financial Services, NBFCs, Stamp Act and related issues /by Vinod Kothari ConsultantsSEBI’s stringent norms for secured debentures

/0 Comments/in Bond Market, Capital Markets, Corporate Laws, Covered Bonds, SEBI /by Vinod Kothari ConsultantsWill it lead to a paradigm shift to unsecured debentures?

Shaifali Sharma | Vinod Kothari and Company

Introduction

The debt market in India has seen significant growth over the years. Amongst the various debt instruments, debentures are one of the most widely used instruments for raising funds. In India, the regulatory framework for debt instruments is governed by multiple regulators through multiple regulations. As far as secured debentures are concerned, more stringent provisions have been prescribed by the respective regulators to protect the interest of investors. In theory, it seems that hard earned money invested by the investors in secured debentures are safe and secured against the assets of the company. However, some major defaults witnessed by debt market in the recent years depict a different reality.

Absence of identified security, delay in payment due to debenture holders and other increased events of defaults witnessed in recent years, has encouraged SEBI to revise the regulatory framework in relation to secured debentures and Debenture Trustees and thereby SEBI vide its circular[1] dated November 03, 2020 (‘November 03 Circular’), has issued norms with respect to the security creation and due diligence of asset cover in furtherance to the recent amendment made in ILDS Regulations[2] and DT Regulations[3] w.e.f. October 8, 2020. Subsequently, on November 13, 2020, SEBI issued circular on Monitoring and Disclosures by Debenture Trustee[4], effective from quarter ended on December 31, 2020 for listed debt securities dealing with various issues namely monitoring of ‘security created’ / ‘assets on which charge is created’, action to be taken in case of breach of covenants or terms of issue, disclosure on website by Debenture Trustee and reporting of regulatory compliance.

The revised framework may pose challenges for corporates to raise fund through secured debentures and may leave them relying on unsecured debentures. In this article we shall discuss and analyse the impact and consequences of these stricter norms on companies and the way forward.

Current Scenario of Corporate Bond Market in India

The RBI Bulletin January, 2019[5] provides that the “total resource mobilisation by Indian corporates through public/private/rights issues is dominated by debt while equity accounts for close to 38%”.

In India, the corporate bond market is dominated by private placements, a graphical trend comparing corporate debt issuance under two routes i.e. public issue and private placement has been given below (‘table 1’). As per the latest data available with SEBI, the total amount raised through corporate bonds by way of private placement has increased from 4,58,073 crores to 6,74,702 crores in the last 5 years.

Table on amount raised through public and private placement issuances of Corporate Bonds in Indian Debt Market (Listed Securities)

| Financial Year | No. of Public Issues | Total amount raised through Public Issue (in crores) | No. of Private Placement (in crores) | Total amount raised through Private Placement (in crores) |

| 2015-16 | 20 | 33811.92 | 2975 | 458073.48 |

| 2016-17 | 16 | 29547.15 | 3377 | 640715.51 |

| 2017-18 | 7 | 4953.05 | 2706 | 599147.08 |

| 2018-19 | 25 | 36679.36 | 2358 | 610317.61 |

| 2019-20 | 34 | 14984.02 | 1787 | 674702.88 |

| 2020-21 (till Oct) | 5 | 881.82 | 1157 | 442526 |

Source: Compiled from data available at SEBI’s website[6]

Table 1: Corporate Debt Issuance under Private Placement and Public Issue

As regards the concentration of secured borrowing in comparison to the unsecured borrowing in private placement market, the RBI Bulletin January 2019 further provides that ‘secured lending accounted for close to half of the total amount raised even in the private placement market of corporate debt’. The same may be understood from a graphical presentation below:

Source: RBI Bulletin January 2019

This includes secured and unsecured borrowing raised in the private placement market of corporate debt

As also noted by SEBI in its consolidation paper[7] dated February 25, 2020, in last 5 Financial Years the bond issuances were largely secured (approximately 76%).

Therefore, the above figures indicate that the volume of corporate bonds, particularly in private placement market, is higher in secured borrowings.

Regulatory Framework for issuing Secured Debentures

SEBI’s stringent norms for issuance of secured debentures

A company may issue secured debentures after complying with the extensive provisions as prescribed under the Companies Act, 2013 and SEBI Regulations. Further SEBI, in view of the increased events of defaults, challenges in relation to creation of charge, enforcement of security, Inter-Creditor Agreement process and other related issues, has reviewed the regulatory framework for Corporate Bond and Debenture Trustee and revisited the manner of issue of secured debentures by introducing amendments in DT Regulations[8], ILDS Regulations[9] and Listing Regulations[10] w.e.f October 08, 2020.

In furtherance to the above amendments made in ILDS Regulations and DT Regulations, SEBI vide November 03 Circular issued norms applicable to secured debentures intended to be issued and listed on or after January 01, 2021.

While the amended provisions aim to secure the interest of debenture holders, the same has raised compliance burden on issuer of secured debentures and thereby corporates may be inclined towards unsecured borrowing facilities due to following reasons:

- Creation of Recovery Expense Fund (REF)

Issuers shall create a Recovery Expense Fund (‘REF’) towards the recovery of proceeding expenses in case of default. The manner of creation, operation and utilization of Fund is prescribed by SEBI vide circular[11] dated October 22, 2020. It requires the Issuer to deposit 0.1% of the issue subject to a maximum of 25 lakhs per issuer. This means that all issuers with an issue size above of 250 crores will be required to deposit 25 lakhs to the REF irrespective of the amount.

All the applications for listing of debt securities made on or after January 01, 2021 shall comply with the condition of creation of REF and the existing issuers whose debt securities are already listed on Stock Exchange(s) shall be given additional time period of 90 days to comply with creation of REF.

This fund is in addition to the requirement of creation of Debenture Redemption Reserve and Debenture Redemption Fund and therefore would entails additional compliance cost to the issuer.

- Due diligence by Debenture Trustee for creation of security

The Debenture Trustee is required to assess that the assets for creation of security are adequate for the proposed issue of debt securities. However, there is no clarity on who is to bear the cost of due diligence. In case the same is to be borne by the issuer, the issue expense will unnecessarily increase.

In case of creation of further charge on assets, the Debenture Trustee shall intimate the existing charge holders via email about the proposal to create further charge on assets by issuer seeking their comments/ objections, if any, to be communicated to the Debenture Trustee within next 5 working days.

In cases where issuers have common Debenture Trustee for all issuances and the charge is created in favour of Debenture Trustee, the requirement seems impracticable.

- Creation of security and strict time frame of listing debentures through private placement

The November 03 Circular mandates creation of charge and execution of Debenture Trust Deed with the Debenture Trustee before making the application for listing of debentures.

SEBI vide its circular[12] dated October 5, 2020, effective for issuance made on or after December 1, 2020, requires the listing of private placement to be completed within 4 trading days from the closure of the issue. Where the issuer fails to do so, he will not be able to utilize issue proceeds of its subsequent two privately placed issuance until final listing approval is received from stock exchanges and will also be liable to penalty as may be prescribed.

In such scenario, it would be arduous for issuers and Debenture Trustee to comply with the procedural requirements in such stringent timelines.

- Entering into Inter-Creditor Agreement (ICA)

An ICA is an agreement between all lenders of a borrower through which lenders collectively initiate the process of implementing a Resolution Plan as per RBI guidelines in case of default. These provisions are applicable to Scheduled Commercial Banks, All India Term Financial Institutions like NABARD, SIDBI etc., small finance banks and NBFC-D. Trustees may join the ICA subject to the approval of debenture holders and conditions prescribed. Debenture Trustee may subject to the approval of debenture holders enter into ICA as per the RBI framework.

- While the ICA is entered with the approval of debenture holders, however, the debenture holders may not be familiar of the concept of ICA and consequences, positive / negative, of joining ICA resulting into uninformed decision.

- RBI guidelines on ICA applies to institutional entities and it does not provide any rights for debenture holders.

- While the Debenture Trustee is free to exit the ICA, it will be challenging to exit ICA and enforce security in case of pari-passu charge.

In addition to the reasons stated above, other stringent compliances as introduced by the SEBI may impose burden and encourage corporates to give a second thought on shifting to unsecured debentures.

Should issuers move towards unsecured debt raising?

While the amendments focus on secured debentures, yet one of the major points in the SEBI Consultation Paper was creation of an ‘identified charge’ on assets. The proposal was in the light of the fact that in case of issuers like NBFCs, the debentures are secured by way of floating charge on receivables. Now, as is known, floating charges are enterprise-wide charges hovering on general assets of the company, unlike fixed charges. Floating charges are subservient to fixed charges. Further, the extant provisions of the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code are not clear on the treatment of floating charges vis-à-vis unsecured debt. Hence, the prevalence of floating charges on receivables is not of much relevance in the case of issuers like NBFCs. Therefore, ‘secured’ debentures, might actually be an illusion and may have no concrete effect. Hence, with more stringent conditions coming in, it might actually be a motivation to the issuers to move to unsecured debentures.

Fund raising via unsecured debentures and applicability of Deposit Rules

Given the stringent regulatory framework for issuance and listing of secured debentures as discussed above, corporates may start looking for other sources of raising funds, including unsecured debt issuances. In case of issue of unsecured debentures, one has to see the applicability of the Companies (Acceptance of Deposits) Rules, 2014 (‘Deposits Rules’) or Non-Banking Financial Companies Acceptance of Public Deposits (Reserve Bank) Directions, 2016[13] (‘NBFC Deposit Directions’), in case of NBFCs, in this regard.

Applicability of Deposit Rules / NBFC Deposit Directions for issuance of unsecured debentures

| Applicability | Whether deposits? | |

| Secured debentures | Unsecured debentures

|

|

| For Companies

(on which Deposits Rules apply) |

Secured debentures shall not be considered as deposits

Explanation: Definition of ‘deposit’ under Rule 2 (1)(c)(ix) of the Companies (Acceptance of Deposits) Rules, 2014 excludes debentures which are secured by first charge or a charge ranking pari passu with the first charge on any assets referred to in Schedule III of the Companies Act, 2013 excluding intangible assets of the company or bonds or debentures compulsorily convertible into shares of the company within ten years. Further, if such bonds or debentures are secured by the charge of any assets referred to in Schedule III of the Act, excluding intangible assets, the amount of such bonds or debentures cannot exceed the market value of such assets as assessed by a registered valuer. |

Unsecured debentures shall be considered as deposits, unless listed on any recognized Stock Exchange.

Explanation: Amount raised by issue of unsecured non-convertible debentures listed on a recognised stock exchange as per applicable regulations made by SEBI shall not be considered as deposits since exempted under Rule 2(1)(c)(ixa) of the Companies (Acceptance of Deposits) Rules, 2014. |

| For NBFCs

(on which NBFC Deposits Directions apply) |

Secured debentures shall not be considered as public deposits

Explanation: As per the definition of ‘public deposit’ under para 3(xiii)(f) of the Master Direction – Non-Banking Financial Companies Acceptance of Public Deposits (Reserve Bank) Directions, 2016, any amount raised by the issue of bonds or debentures secured by the mortgage of any immovable property of the company; or by any other asset or which would be compulsorily convertible into equity in the company provided that in the case of such bonds or debentures secured by the mortgage of any immovable property or secured by other assets, the amount of such bonds or debentures shall not exceed the market value of such immovable property/other assets; |

Unsecured debentures shall be considered as public deposits, except in case of issuance of non-convertible debentures with a maturity more than one year and having the minimum subscription per investor at Rs.1 crore and above

Explanation: As per para 3(xiii)(fa) of said Master Directions, any amount raised by issuance of non-convertible debentures with a maturity more than one year and having the minimum subscription per investor at Rs.1 crore and above, provided that such debentures have been issued in accordance with the guidelines issued by the Bank as in force from time to time in respect of such non-convertible debentures shall not be treated as public deposits. |

Thus, the debentures will either have to be secured, or will have to be listed in order to avail exemption from the Deposit Rules/ NBFC Deposit Directions.

Compliance Corner: How different is unsecured from secured debentures?

A brief comparison of the requirements of issuance of secured and unsecured debentures is summarized below:

| Sr. No. | Basis of Comparison | Section/ Rule | Secured Debentures | Unsecured Debentures |

| 1. | Creation of security | Section 71(3) of the Companies Act, 2013 read with Rule 18 of Companies (Share Capital and Debentures) Rules, 2014 (‘Debenture Rules, 2014’) | Secured by the creation of a charge on the properties or assets of the company or its subsidiaries or its holding company or its associates companies, having a value which is sufficient for the due repayment of the amount of debentures and interest thereon.

Charge or mortgage shall be created in favour of the debenture trustee on:

|

No security created. |

| 2. | Registration of charge | Section 77 of the Companies Act, 2013 | Issuer shall register the charge within 30 days of its creation/ modification or such additional period as may be prescribed. | Not Applicable |

| 3. | Redemption Period | Rule 18(1)(a) of Debentures Rules, 2014 | To be redeem within 10 years from the date of issue

Companies engaged in setting up infrastructure projects, infrastructure finance companies, infrastructure debt fund NBFCs and companies permitted by the CG, RBI or any other statutory authority may issue for a period exceeding 10 years but not exceeding 30 years. |

No redemption time frame prescribed for unsecured debentures. |

| 4. | Voting Rights | Section 71(2) the Companies Act, 2013 | Does not carry voting rights | Does not carry voting rights |

| 5. | Creation of Debenture Redemption Reserve (DRR) | Section 71(4) read with Rule 18(7) of Debentures Rules, 2014 | DRR/DRF requirement does not depend whether debentures are secured or unsecured, rather it depends on the type of company and the mode of issue i.e. public issue or private placement. | Subject to same provisions

|

| 6. | Appointment of Debenture Trustee | Section 71(5) read with Rule 18(1)(c), (2) of Debenture Rules, 2014 | Required in case the offer or invitation is made to the public or if the total number of members exceeds 500 for the subscription of debentures [Section 71(5)].

ILDS requires appointment of DT in case of every listed debentures. |

Subject to same provisions |

| 7. | Duties of Debenture Trustee | Section 71(6) read with Rule 18(3) & (4) of the Debenture Rules, 2014, SEBI (ILDS) Regulations, 2008 and SEBI (DT) Regulations, 1993 | In accordance with provisions of Section 71(6) read with Rule 18(3) & (4) of the Debenture Rules, 2014

Other obligations as prescribed under SEBI (ILDS) Regulations, 2008 and SEBI (DT) Regulations, 1993 |

Subject to same provisions |

| 8. | Failure to redeem or pay interest on debentures | Section 71(10), 164(2) of the Companies Act, 2013 |

|

Subject to same provisions |

| 9. | Listing of Debentures | SEBI (ILDS) Regulations, 2008, SEBI (LODR) Regulations, 2015 | Issuer to comply with the provisions of SEBI (ILDS) Regulations, 2008. Post listing, the issuer, in addition to SEBI (ILDS) Regulations, 2008, shall also comply with provisions of SEBI (LODR) Regulations, 2015 and SEBI (Prohibition of Insider Trading) Regulations, 2015. | Subject to same provisions |

Neither the Companies Act, 2013 nor the Debenture Rules, 2014 elaborate the manner of issue of unsecured debentures. However, the provisions for issue of unsecured debentures are almost the same as that for secured debentures except certain conditions such as redemption period, requirement of creation of charge on the assets of the issuer and filing charge with the Registrar of Companies.

Investors perspective may also prove the same stand –the unsecured debentures don’t carry securities against any assets of the company unlike in case of secured debenture, however the debenture-holder(s) or the Debenture Trustee may approach the Tribunal which may then direct the company to honour its debt obligations.

Concluding Remarks

From the issuer’s perspective, the debentures have to be secured so as to escape from the Deposit Rules. This is one of the main reasons why companies issue secured debentures. While the issuer may be able to avoid the rigorous compliances of Deposits Rules, issuing secured debentures have apparently become very stringent.

From investor’s viewpoint, it may seem that the investment in secured debentures is safe as company has created charge on its assets sufficient to discharge the principle and interest amount. Yet some major defaults in past have made the investors more hesitant to invest in the secured debentures.

While at this stage it was important for SEBI to make the norms more stringent to safeguard the interest of the debenture holders, however, it will be challenging for the issuers to comply with such norms, failing which they may be inclined towards issuance of unsecured debt issuances.

Although unsecured debentures do not provide any security against investment, issuer may still rewards investors with higher yields which is a pay-off for increased risk taken by the investor.

Given the new compliance burden and their stringencies for issuance and listing of secured debentures, it will be interesting to see how the ratio of secured and unsecured borrowings changes in the coming years. For the sake of it, the upcoming trends, preferences and acceptability of stringencies by the corporates will be very vital for observation.

Other reading materials on the similar topic:

- ‘This New Year brings more complexity to bond issuance as SEBI makes it cumbersome’ can be viewed here

- ‘SEBI responds to payment defaults by empowering Debenture Trustees’ can be read here

- Our other articles on various topics can be read at: http://vinodkothari.com/

Email id for further queries: corplaw@vinodkothari.com

Our website: www.vinodkothari.com

Our Youtube Channel: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCgzB-ZviIMcuA_1uv6jATbg

Our presentation on structures of debt securities can be viewed here – https://vinodkothari.com/2021/09/structuring-of-debt-instruments/

[1] https://www.sebi.gov.in/legal/circulars/nov-2020/creation-of-security-in-issuance-of-listed-debt-securities-and-due-diligence-by-debenture-trustee-s-_48074.html

[2] SEBI (Issue and Listing of Debt Securities) Regulations, 2008

[3] SEBI (Debenture Trustees) Regulations, 1993

[4] https://www.sebi.gov.in/legal/circulars/nov-2020/monitoring-and-disclosures-by-debenture-trustee-s-_48159.html

[5] https://rbidocs.rbi.org.in/rdocs/Bulletin/PDFs/2ICBMIMM141CFFF458BB4B3A9F4C006F4AE4897F.PDF

[6] https://www.sebi.gov.in/statistics/corporate-bonds/privateplacementdata.html

[7] https://www.sebi.gov.in/reports-and-statistics/reports/feb-2020/consultation-paper-on-review-of-the-regulatory-framework-for-corporate-bonds-and-debenture-trustees_46079.html

[8] http://egazette.nic.in/WriteReadData/2020/222323.pdf

[9] http://egazette.nic.in/WriteReadData/2020/222324.pdf

[10] SEBI (Listing Obligations and Disclosure Requirements) Regulations, 2015

[11] https://www.sebi.gov.in/legal/circulars/oct-2020/contribution-by-issuers-of-listed-or-proposed-to-be-listed-debt-securities-towards-creation-of-recovery-expense-fund-_47939.html

[12] https://www.sebi.gov.in/legal/circulars/oct-2020/standardization-of-timeline-for-listing-of-securities-issued-on-a-private-placement-basis_47790.html

[13] https://www.rbi.org.in/Scripts/NotificationUser.aspx?Id=10563&Mode=0#C2

Market Linked Debentures – Adding Flavour to Plain Vanilla Bonds

/0 Comments/in Bond Market, Capital Markets, Corporate Laws /by Vinod Kothari Consultants Loading…

Loading…

Sale of Legal Entity as an Asset: A step towards value maximization

/0 Comments/in Corporate Laws, Insolvency and Bankruptcy /by Vinod Kothari Consultants–Megha Mittal

Maximization of value of assets of the corporate debtor is one of the primary objectives of the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016 (“Code”/ “IBC”); and it is towards this objective that the Code requires a mandatory corporate insolvency resolution process to ensue prior to liquidation. The rationale behind such specified order is that under corporate insolvency resolution process, the corporate debtor is taken over as a going concern, which as per settled economic argument attracts a much better value via-a-vis disposal of assets. It is in view of such rationale that the liquidation laws also provide sufficient flexibility to keep the corporate debtor a going-concern even after commencement of liquidation[1].

Having said so, while the Liquidation Regulations allow sale of the corporate debtor as a going-concern, one cannot overlook the fact that the likelihood of the going-concern sale is already rusted by the time the corporate debtor reaches the liquidation stage.

It is a common economic understanding that sum of parts is better than sum of the parts; and it is by virtue of such principle that going-concern values are generally in excess of value of individual assets. The various assets, stitched together as one, constitute a much greater value than the same assets in isolation.

In this backdrop, what may be considered as a rather unexplored territory is the prospect of sale of the legal entity only, sans the other assets that the corporate debtor may have. In this note, we analyse and put forth a case for saleability of legal entity itself, without other conventional assets, under the Code.

Presentation on Co-Lending Guidelines

/0 Comments/in Financial Services, NBFCs /by Vinod Kothari ConsultantsCorporate Restructuring- Corporate Law, Accounting and Tax Perspective

/0 Comments/in Accounting and Taxation, Companies Act 2013, Corporate Laws, Direct Taxes, Indian Accounting Standards (Ind AS), Schemes and Arrangements, SEBI /by Vinod Kothari Consultants–Resolution Division

Restructuring is the process of redesigning one or more aspects of a company, and is considered as a key driver of corporate existence. Depending upon the ultimate objective, a company may choose to restructure by several modes, viz. mergers, de-mergers, buy-backs and/ or other forms of internal reorganisation, or a combination of two or more such methods.

However, while drafting a restructuring plan, it is important to take into consideration several aspects viz. requirements under the Companies Act, SEBI Regulations, Competition Act, Stamp duty implications, Accounting methods (AS/ Ind-AS), and last but not the least, taxation provisions.

In this presentation, we bring to you a compilation of the various modes of restructuring and the applicable corporate law provisions, accounting standards and taxation provisions.

New Model of Co-Lending in financial sector

/0 Comments/in Financial Services, NBFCs, RBI, Uncategorized /by Vinod Kothari ConsultantsScope expanded, risk participation contractual, borders with direct assignment drawn

-Team Financial Services (finserv@vinodkothari.com)

[This version dated 20th March, 2021]

Co-lending is coming together of entities in the financial sector – mostly, something that happens between banks and NBFCs, or larger banks and smaller banks. Financial interfaces between different financial entities may take the form of securitisation, direct assignment, co-lending, banking correspondents, loan referencing, etc.

While direct assignment and securitisation have been around for quite some time, co-lending was permitted by the RBI under its existing guidelines on ‘Co-origination of loans between banks and NBFC-SIs for granting loan to the priority sector’[1]. As per the Statement on Developmental and Regulatory Policies issued by the RBI dated October 9, 2020, it was decided to expand the scope of co-lending, currently permitted only for NBFC-SIs, to all NBFCs. Accordingly, the RBI came, vide notification on co-lending by banks and NBFCs (Co-Lending Model/CLM)[2] dated November 5, 2020, with a new regulatory framework for co-lending, of course, in case of priority sector loans. The CLM supersedes the existing guidelines on co-origination.

There is no clarity, still, on whether the non-priority sector loans (PSL or Non-PSL) will also be covered by this regulatory discipline, or any discipline for that matter. In this write-up, we explore the key features of the co-lending regime, and also get into tricky questions such as applicability to non-PSL loans, the borderlines of distinction between direct assignments and co-lending, the sharing of risks and rewards, etc.

Applicability

The erstwhile Regulations for priority sector lending covered co-lending transactions of Banks and Systemically Important NBFCs. However, under the Co-Lending Model.The CLM covers all NBFCs (including HFCs) in its purview.

There is a whole breed of new-age fintech companies using innovative algo-based originations, and aggressively using the internet for originations, and these companies pass a substantial part of their lending to either larger NBFCs or to banks. Thus, the expanded ambit of the Co-Lending Model will increase the penetration and result into wider outreach, meet the objective of financial inclusion, and potentially, reduce the cost for the ultimate beneficiary of the loans. Smaller NBFCs have their own operational efficiencies and distribution capabilities; hence, this is a welcome move.

Further, the RBI has excluded foreign Banks, including wholly owned subsidiaries of foreign banks, having less than 20 branches, from the applicability of the CLM. Also, Small Finance Banks, Regional Rural Banks, Urban Cooperative Banks and Local Area Banks have been excluded from the applicability of CLM.

An interesting question that comes up here is whether such exclusion should be construed as a restriction on such entities from entering into co-lending transactions, or a relaxation from the applicability of the Co-Lending Model? It may be noted that the CLM a precondition for PSL treatment of the loans. This is clear from the title ‘Co-Lending by Banks and NBFCs to Priority Sector’. The intent is not to put a bar on existence of co-lending arrangements outside the CLM. That is to say, if the loan, originated by the principal co-lender, is a priority sector loan, then the participating co-lender will also be able to treat the participant’s share of the loan as a PSL, subject to adherence to the conditions specified in CLM. The implication of this is that where the loan does not meet the conditions of CLM, then the participating bank will not be able to accord a PSL status, even though the loan in question is a PSL loan.

With that rationale, in our view, there is no absolute prohibition in the excluded banking entities from being a co-lender. However, if the major motivation of the co-lending mechanism under the CLM is the PSL tag, that tag will not be available to the excluded banks, and hence, the very inspiration for falling under the arrangement may go away. This is also clear from the PSL Master Directions[3] which recognises co-origination of loans by SCBs and NBFCs for lending to the priority sector and specifically excludes RRBs, UCBs, SFBs and LABs.

Applicability date and the fate of existing transactions

In the absence of any specified timelines, the CLM supersedes the existing co-lending guidelines with immediate effect. However, it specifies that outstanding loans in terms of the erstwhile guidelines would continue to be classified under priority sector till their repayment or maturity, whichever is earlier.

This would mean grandfathering of existing loans, and not existing lending arrangements. That is to say, if there are existing co-lending arrangements, but the loan in question has not yet originated, even existing co-lending arrangements will have to abide with the Co-Lending Model. Needless to say, any new co-lending arrangements will nevertheless have to abide by the Co-Lending Model.

As we note below, one of the very important features of the Co-Lending Model is that risk-sharing and loan-sharing do not have to follow the same proportion. Additionally, it is possible for the participating bank to have an explicit recourse against the originating co-lender. This feature was not available under the earlier framework. This alone may be a sufficient motivation for existing CLMs to be revised or redrawn.

Co-lending, Outsourcing and Direct Assignment – new borderlines of distinction

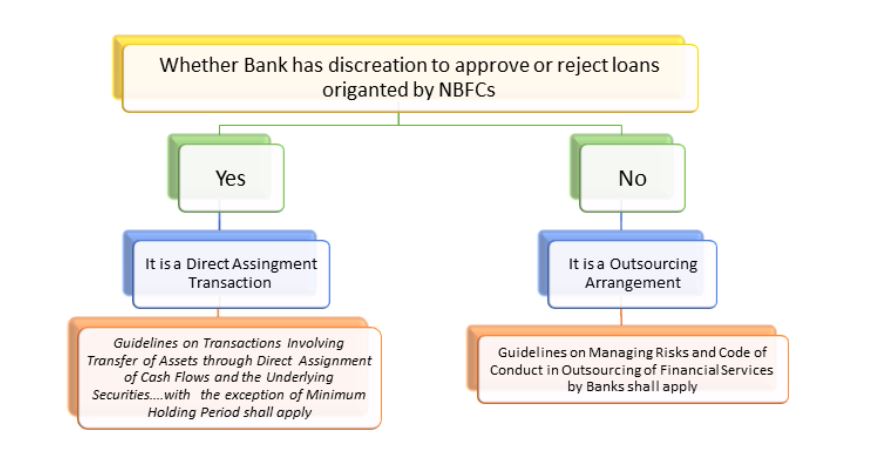

For the purpose of entering into co-lending transactions, banks and NBFCs will have to enter into a ‘Master Agreement’. Such agreement may require the bank either to mandatorily take the loans originated by the NBFC on its books or retain discretion as to taking the loans on its books.

Where the participating bank has a discretion as to taking its share of the loans originated by the originating partner, the transaction partakes the character of a direct assignment. Para 1(c) of the CLM says that ”…if the bank can exercise its discretion regarding taking into its books the loans originated by NBFC as per the Agreement, the arrangement will be akin to a direct assignment transaction. Accordingly, the taking over bank shall ensure compliance with all the requirements in terms of Guidelines on Transactions Involving Transfer of Assets through Direct Assignment of Cash Flows and the Underlying Securities….with the exception of Minimum Holding Period (MHP) which shall not be applicable in such transactions undertaken in terms of this CLM.

That would mean, a precondition for the arrangement being treated as a CLM is that the participating bank takes the loans originated by the originating partner without discretion exercisable on a cherry-picking basis.

Does this mean that irrespective of whether the loan originated by the originating partner fits into the credit screen of the bank or not, the bank will still have to take it, lying low? certainly, this is not the intent of the CLM This is what comes form clause 1(a)- ‘…..the partner bank and NBFC shall have to put in place suitable mechanisms for ex-ante due diligence by the bank as the credit sanction process cannot be outsourced under the extant guidelines.’

Thus, even in case the bank gives a prior, irrevocable commitment to take its share of exposure, the same shall be subject to an ex-ante due diligence by the bank. Ex-ante obviously implies a prior As per the outsourcing guidelines for banks[4], the credit sanction process cannot be outsourced. Accordingly, it must be ensured that the credit sanction process has not been outsourced completely and the bank retains the right to carry out the due diligence as per its internal policy. Notwithstanding the bank’s due diligence exercise, the co-lending NBFC shall also simultaneously carry out its own credit sanction process.

The conclusion one gets from the above is as follows:

- The essence of co-lending arrangement is that the participating bank relies upon the lead role played by the originating bank. The originating bank is the one playing the fronting role, with customer interface. The credit screens, of course, are pre-agreed and it will naturally be incumbent upon the originating bank to abide by those. Hence, on a case by case basis or so-called “cherry picking” basis, the participating bank is not selecting or dis-selecting loans. If that is what is being done, the transaction amounts to a DA.

- Subject to the above, the participating bank is expected to have its credit appraisal process still on. Where it finds deviations from the same, the participating bank may still decline to take its share.

It is important to note that if DA comes into play, the requirements such as MHP, MRR, true sale conditions will also have to be complied with. However, co-lending transactions do not have any MHP requirements, unlike in case of either DA or securitiastion. Of course co-lending transactions do have a risk retention stipulation, as the CLM require a 20% minimum share with the originating NBFC. Hence, the intent of the RBI is that co lending mechanism must not turn out to be a regulatory arbitrage to carry out what is virtually a DA, through the CLM.

(Almost) A new model of direct assignments: assignments without holding period

Para 1 c. of the Annex seems to be leading to a completely new model of direct assignments – direct assignments without a holding period, or so-called on-tap direct assignments. Reading para 1 c. suggests that while co-lending takes the form of a loan sharing at the very inception, the reference in para 1 c. is to loans which have already been originated by the NBFC, and the participating bank now cherry-picks some or more of those loans. The cherry-picking is evident in “if the bank can exercise its discretion regarding taking into its books the loans originated by NBFC”. However, unlike any other direct assignment, this assignment happens on what may be called a back-to-back arrangement, that is, without allowing for lapse of time to see the loan in hindsight.

In essence, there emerge 3 possibilities:

- A non-discretionary loan sharing, which is the usual co-lending model, where the originating co-lender has a minimum 20% share.

- A discretionary, on-tap assignment, where the originating assignor needs to have a minimum 20% share

- A proper direct assignment, with minimum holding period, where the assignor needs to have a minimum 10% share.

The on-tap assignment referred to above seems to be subject to all the norms applicable to a direct assignment, other than the minimum holding period.

Interest Rates

The erstwhile guidelines require that the interest rate charged on the loans originated under the co-lending guidelines would be calculated as per Blended Interest Rate Calculations, that is to say the rate shall be calculated by assigning weights in proportion to risk exposure undertaken by each party, to the benchmark interest rate of the respective lender.

The current guidelines require that the interest rate shall be an all inclusive rate that is mutually agreed by the parties. However it shall be ensured that the interest rate charged is not excessive as the same would breach the provisions of fair practice code, which is to be compulsorily complied.

This change would provide flexibility to the lenders and also ensure that the cost incurred in tracing and disbursals to remote sectors as well as enhanced risk exposure is appropriately compensated.

Determining the roles

Under the erstwhile provisions, it was mandatory that the share of the co-lending NBFC shall be at least 20%. The same has been retained in the CLM as well, requiring NBFCs to retain a minimum of 20% share of the individual loans on their books.

Under the CLM, the co-lending NBFC shall be the single point of interface for the customers. Further, the grievance redressal function would also have to be carried out by the NBFC.

Operational Aspects

Escrow Account

For the purpose of disbursals, collections etc. an escrow account should be opened. The co-lending banks and NBFCs shall maintain each individual borrower’s account for their respective exposures. It is only for the purpose of avoiding commingling of funds, that an escrow mechanism is required to be placed. The bank and NBFC shall, while entering into the Master Agreement, lay down the rights and duties relating to the escrow account, manner of appropriation etc.

Creation of Security

The manner of creation of charge on the security provided for the loan shall be decided in the Master Agreement itself.

Accounting

Each of the lenders shall record their respective exposures in their books. The asset classification and provisioning shall also be done for the respective part of the exposure. For this purpose, the monitoring of the accounts may either be done by both the co-lenders or may be outsourced to any one of them, as agreed in the Master Agreement. Usually, the function of monitoring remains with the NBFC (since, it has done the origination and deals with the customer.)

Non-PSL loans: whether the framework would apply in pari materia?

The guidelines on CLM have been issued for co-lending of loans that qualify for the purpose of priority sector lending. This does not bar lenders from entering into co-lending transactions outside the purview of these guidelines. The only difference it would make is such loans would not be eligible to be classified as loans to the priority sector (which is the primary motive for banks to enter into co-lending transactions).

This seems to form a view that the guidelines would not at all be applicable in case of non-priority sector loans. However, for a transaction to be a co-lending transaction, there has to be adequate risk sharing between the co-lenders. Hence, the guidelines on CLM shall be applicable in pari-materia.

[1] https://www.rbi.org.in/Scripts/NotificationUser.aspx?Id=11376&Mode=0

[2] https://www.rbi.org.in/Scripts/NotificationUser.aspx?Id=11991&Mode=0

[3] https://www.rbi.org.in/Scripts/NotificationUser.aspx?Id=11959&Mode=0

[4] https://www.rbi.org.in/scripts/NotificationUser.aspx?Id=3148&Mode=0

Other related write-ups: