Archive for month: September, 2020

Revised timelines for various compliances under CA, 2013

/0 Comments/in Corporate Laws, Corporate Laws - Covid-19, Covid-19, MCA, UPDATES /by Vinod Kothari ConsultantsSEBI Guidelines for Investment Advisers

/0 Comments/in Corporate Laws, SEBI /by Vinod Kothari ConsultantsValuation approaches and methods

/0 Comments/in Financial Services, Valuations /by Vinod Kothari ConsultantsAbhirup Ghosh

| Approach | Method | Description | Application |

| Cost/ Asset based approach | Replacement cost method | This method is based on the concept of replacement i.e. Similar Utility. It considers the cost involved in replacing the assets of the Company at the same level on the date of valuation as the value of the Business of the Company. It is also known as substantial value. | · The subject company is not directly income generating or application of income approach or market approach is not feasible.

· The basis of value used in valuation assignment is dependent on the cost approach. E.g. replacement value, liquidation value. · For checking the reasonableness of the value derived from other approaches. |

| Reproduction cost method | In this approach the value of the Company is the cost involved in creating the exact replica of the subject Company from scratch as on the date of valuation. | ||

| Summation method | It is also called as the Underlying assets approach. Summation Method involves the separate valuation of each category or component of assets of the subject Company. The total value of the subject Company is the additive sum (therefore the name summation) of the values of the individual asset categories. Whatever categories of assets are encompassed in the subject Company are summed (or added in) the summation valuation. | ||

| Net assets value method/ Book value method | Here the book value assets and liabilities are considered. The liabilities and fictitious assets are reduced from the total assets arrive at the net assets value of the Company. This value is also equivalent to the net worth of the Company. | ||

| Adjusted net asset value method | A variation of the NAV method. Here the assets and liabilities are adjusted and considered at their fair values instead of their book values. | ||

| Market approach | Comparable company method | Here the value of a company is evaluated by using trading multiples derived from publicly traded companies like the subject Company.

Some common multiples used for valuing a company under this method are:

· Price to sales Multiple · Price Earnings Ratio · Price to Book Value · EV/Sales · EV/EBITDA |

· Subject Asset or Similar asset is actively publicly traded.

· Subject assets or substantially similar asset has been sold transaction appropriate for consideration under basis of value. · There are recent / frequent transactions in substantially similar assets. |

| Comparable transaction method | In this method the value is derived based on pricing metrics of mergers and acquisitions involving controlling interests in companies (public and private) in the same or similar line of business as the subject company. | ||

| Income approach | Capitalisation of earnings method | In this method, the past profits of the Company are capitalized at expected return on equity. Also known as Profit Earning Capacity Value. Alternatively, instead of the capitalization at the expected return on equity, the PE multiple is also applied to arrive at the value of the Company. | Can be applied where there is no market comparable for the subject company. |

| Discounted cash flow method | Under Discounted cash flow (DCF) Method, the total value of a business is calculated as the present value of its expected future cash flows over the projected period and present value of terminal value / Cash flows i.e. the free cash flows are discounted by an appropriate discounting factor. Under DCF method, two variants are used to value a company and its equity one is free cash flow to the firm (FCFF) and other is free cash flow to equity (FCFE). |

Related wrote-ups:

Sec 29A in the Post-COVID World- To stay or not to stay

/0 Comments/in Insolvency and Bankruptcy /by Vinod Kothari Consultants-Megha Mittal

If the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016 (‘Code’) is the car driving the ailing companies on road to revival, resolution plans are the wheels- Essentially designed to explore revival opportunities for an ailing entity, the Code invites potential resolution applicants to come forward and submit resolution plans.

Generally perceived as an alluring investment opportunity, resolution plans enable interested parties to acquire businesses at considerably reduced values. An indispensable aspect of these Resolution Plans, however, is the applicability of section 29A, which restricts several classes of entities, including ex-promoters of the corporate debtor, from becoming resolution applicants- for the very simple purpose of preventing re-possession of the corporate debtor at discounted rates. Hence, section 29A is seen as a crucial safeguard in revival of the corporate debtor, in its true sense.

In the present times, however, we cannot overlook the fact that the unprecedented COVID disruption, has compelled regulators around the globe, to reconsider the applicability and continuity of several laws, including those considered as significant; and one such provision is section 29A of the Code.

In a recent paper “Indian Banks: A Time to Reform?” dated 21st September,2020, the authors, Viral V Archarya and Raghuram G. Rajan, the former Deputy Governor and Governor of the Reserve Bank of India, have discussed banking sector reforms in view of the COVID disruption, calling for privatisation of Public Sector Banks, setting up of a ‘Bad Bank’[1] amongst other suggested reforms. In the said Paper, they also suggest that “for post-COVID NCLT cases to allow the original borrower to retain control, with the restructuring agreed with all creditors further blessed by the court. Another alternative might be to allow the original borrower to also bid in the NCLT-run auction”- thereby setting a stage for holding back applicability of section 29A in the post COVID world.

In this article, the author makes a humble attempt to analyse the feasibility and viability of doing-away with section 29A in the post-COVID world.

Stop crazy lending, lazy lending, write Rajan and Acharya

/0 Comments/in Financial Services, RBI /by Vinod Kothari Consultants– Vinod Kothari

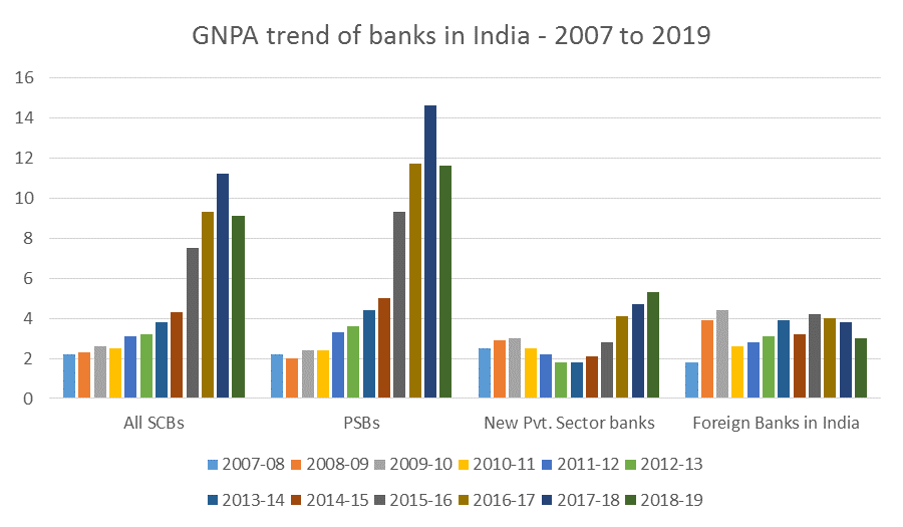

Raghuram Rajan and Viral Acharya, both having got the first-hand experience of holding the reins at the RBI, have prescribed several urgent measures to restore the health of the banking system. Neither do we have the fiscal space to support the banking system with fresh doses of capital, nor can we afford any more spikes in the almost top-of-the-world GNPA ratios. The duo, who have written several articles in the past, wrote this piece[1] on 21st Sept. 2020.

In a strongly worded write-up, the two celebrated academics of the financial world, have clearly taken it out on the bureaucracy and the government. The authors say while advocacy for comprehensive banking sector reforms have been done in the past, the onus of not making it happen is clearly on the government itself: “There are strong interests against change, which is why many would-be reformers are cynical, and either have given up, or recommend revolutionary change that has little chance of being implemented. We are more optimistic that a middle road is achievable, given that the greatest stumbling block has been the government, the bureaucracy, and the interests within it. With the enormous strains on government finances from the slow growth pre-COVID and the subsequent effects of the pandemic, the country has to transform the banking

sector from being a drain on government resources and an impediment to growth to becoming an engine of growth. This will not happen through incremental reforms. The status quo is fiscally untenable.”

The authors are unsparing when they clearly say the Department of Financial Services should be scrapped. The authors recommend that “Winding down Department of Financial Services in the Ministry of Finance is essential, both as an affirmative signal of the intent to grant bank boards and management independence and as a commitment not to engage in “mission creep” when compulsions arise to use banks for serving costly social or political objectives.” They also say that despite clear recommendations of the Nayak Committee in 2014[2], nothing has changed in terms of autonomy of the banks in the country. The authors may be resonating the bitterness of many senior bankers when they say: “Parliamentarians of all parties are not immune to the lure of public sector banks – the banks are often asked to arrange the logistics for their fact-finding committee meetings in enjoyable locales across the country. And Finance Ministry bureaucrats are reluctant to let go of the power that allows a young joint secretary to order the chairpersons of national banks around”

No more crazy lending, lazy lending

Banks in India cannot afford to have the false sense of having safe assets by “lazy lending”. The term, coined by Dr Rakesh Mohan, the-then Deputy Governor of RBI[3], refers to bankers choosing to invest in risk-free government bonds, even when the opportunity cost of capital for them is much higher. At the same time, banks also cannot afford to do “crazy lending”, by lending to riskiest of borrowers as more credit-worthy borrowers choose to rely on capital markets, and thereby, pile up non-performing loans on their balance sheets.

Indian banks, particularly PSUs, have managed to pile up bad loans on their balance sheet. There were sizeable NPAs even before the Covid. Six months of covid-moratorium meant virtually no cashflows, and as the servicing burden on the borrowers has increased over these months, most banks will be forced to use the loan restructuring option following covid-disruption[4]. The contention that the covid-disruption will become the alibi to restructure loans that were even otherwise fragile does not require much evidencing.

Source: Handbook of statistics on the Indian Economy, 2019-20[5]

Rajan and Acharya refer to the well-known ever-greening problem of Indian banking – with the bankers supporting bad loans by sequential doses of further lending, and the promoters continuously stripping the assets out and diverting profits and cashflows, leaving the borrower to be a “zombie”. Authors say that banks, by keeping the zombies alive, do a double damage to the system – on one hand, the bankers continue to focus on bad loan management and therefore, spend less time and resources to creating healthy loans, and on the other, the presence of half-dead firms discourages healthy industries as well.

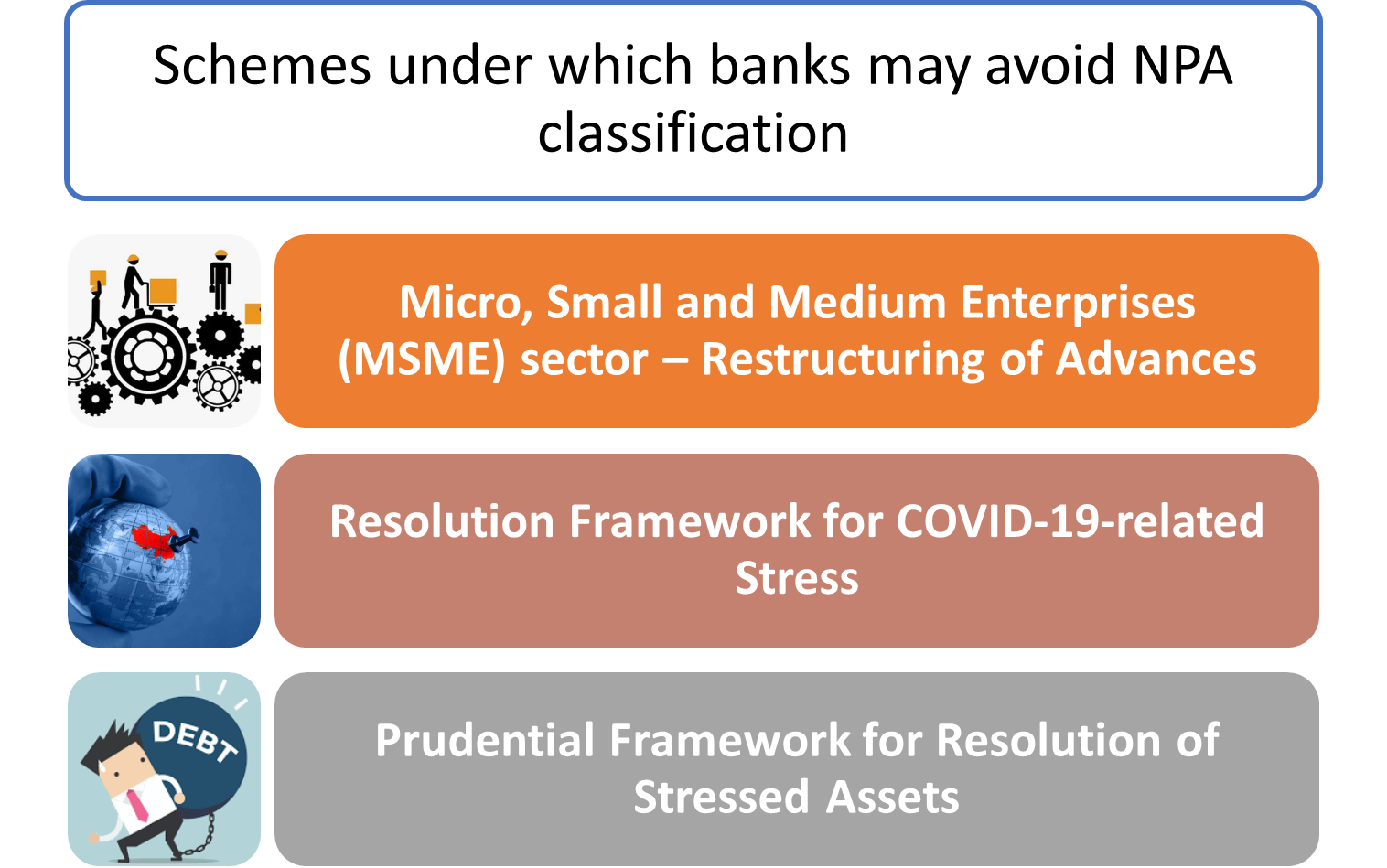

While banks over the world have converged to IFRS, which provides for an “expected loss” model, the Indian banking system is still driven by the regulatory requirement of provisioning, in form of the so-called IRAC (Income recognition and asset classification) norms. However, periodically, the RBI comes with schemes whereby banks can avoid classifying a loan as an NPA.

“With forbearance in the form of delayed provisioning, not only does the firm’s condition deteriorate, but the banker has to take a large loss when he eventually restructures the loan. So instead the banker holds off, under-provisioning mounts, and what was meant to be temporary regulatory forbearance inevitably creates banker demand for more, near-permanent forbearance”, say the authors. The authors say that fear-struck bankers are more comfortable in letting the NCLT process take over the bankers’ resolution, since, in that case, the decisions are made by the NCLT-appointed professional, and not by the bank, who may thus get sheltered by the proverbial 3 Cs that haunt bankers.

Arguing for the need to revisit sec. 29A of the Insolvency Code, Rajan and Acharya say that the provision are needed at the time when the defaulting borrower was to be prevented from buying bank his own assets and potentially scaring other buyers. But in the present scenario of pandemic stress, this will also prevent the promoter whose business faltered for no fault of his. The authors also reflect the reality when the say the NCLT “already has a large backlog of cases, some of which have dragged on for much longer than the targeted duration for bankruptcy. It cannot possibly handle the volume of distress that will have to be dealt with post-pandemic without a significant expansion of the number of its judges and benches. Unfortunately, the quantum of trained personnel that is needed may simply not exist.”

The authors also advocate the retention of the debtors’ control, at least in the post-pandemic restructurings. Notably, the creditors’ in control model that India has adopted, is inspired by the UK approach, whereas the USA has a debtor-in-control approach.

The authors are also in favour of a larger predominance of out-of-court resolutions: “Ideally though, there should be greater use of out-of-court restructuring and the NCLT should be used to stamp the out-of-court restructuring with legal finality. Only if an out-of-court restructuring could not be agreed upon between the creditors and the borrower would the firm be forced into a bankruptcy auction. The shadow of bankruptcy would then improve the ease and quality of the negotiation out of bankruptcy, as it does in other countries. But this requires bankers, especially public sector bankers, to be able to negotiate”

Creation of “bad bank”

The bad bank experience has had a limited success in India. IDBI created SASF in 2004. However, neither did it help the bad loans, nor IDBI. Subsequently, India has worked on a private sector model of so-called “bad banks”, in form of the ARCs. However, the transfer of loans to ARCs may mostly take the form of security receipts, which is paper-for-paper. It is only in the recent past that banks have insisted on all-cash loan transfers.

Hence, authors argue that what may be more effective is a transparent market for bad loans. Notably, the draft Directions for Sale of Loans, issued by the RBI for public comments on 08th June, 2020[6], provided, among other things, an auction-based disposal of bad loans. There is apparently also a discussion on permitting foreign investors to invest in bad loans directly.

Additionally, the authors also suggest the creation of a “public credit registry”. Currently, there are multiple registries in India working with significant overlaps and lack of cohesiveness. CERSAI, NeSL, and CRILC are such registries, each intended to serve different purposes. However, it will not be a high hanging fruit to combine them into a loan registry, where the information about a loan, its collateral, performance, etc. are all pooled into a single database. Authors say that KAMCO, Korea, after completion of its asset management task, is now evolving itself into a loan registry.

Authors suggest that selling of loans will bring transparency and price discovery. Currently, RBI’s regulatory framework has been restraining banks from selling loans, mainly on the concerns of originate-to-hold model.

The authors contend that if a transparent pricing could emerge by creating a secondary market, a bad bank could emerge by the market mechanism itself. These market-based bad banks can have sectoral focus, rather than a generic pool of NPAs as is currently the case. The authors also cite global examples of warehousing bad loans to find a more opportune time for disposing them.

Move from asset-based lending to cashflow-based lending

Lending can be, as it traditionally has been, focused on the on-balance sheet assets and collateral, or may be focused on the cashflows of the business. In case of asset-based lending, the lender focuses on balance sheet ratios such as leverage and loan-to-value. In cash-flow based lending approach, the lender focuses on liquidity and debt-servicing ability.

An RBI Expert Group led by Shri U K Sinha recommended a cash-flow based lending structure for MSME funding[7].

Recently, large Indian banks announced plans to move to cashflow-based lending, such as SBI. SBI Chairman Rajnish Kumar stated “SBI will switch to a cash flow-based lending model beginning April 2020 from a mechanism where loans are given against assets”[8].

The authors have recommended a transition from asset based lending to (also) cash flow based lending. The authors mention that “Banks could rely more on loan covenants for large borrowers, tied to liquidity and leverage ratios (instead of lending purely against assets). This would set up “trip wire” points for enhancing loan collateralization, rather than requiring it from the beginning; in case of small borrowers, reliance on GST invoices and utility payment bills, among other cashflow information, can facilitate such a transition.”

Group-lending limits

The authors talk about the problem relating to certain promoters running large conglomerates while sitting on thin slices of equity. Due to this the following problems are highlighted by the authors, namely, a) this creates systemic risk in the banking system, b) leads to concentration of corporate power and a complex maze of related party transactions between financial and real subsidiaries of the group that are often the veil behind which frauds are perpetrated.

The authors recommend that highly indebted groups should not be allowed to expand their footprint significantly by using bank money to bid on new projects. Group lending norms should be enforced as the economy recovers. Further, the authors state that aggregate permissible system exposures should be linked to the aggregate debt equity ratio for the group (including non-bank borrowing and foreign borrowing). Over-leveraging by specific promoters or groups needs to be limited if the Indian banking system’s health is to be restored.

[1] https://faculty.chicagobooth.edu/-/media/faculty/raghuram-rajan/research/papers/paper-on-banking-sector-reforms-rr-va-final.pdf

[2] https://rbidocs.rbi.org.in/rdocs/PublicationReport/Pdfs/BCF090514FR.pdf

[3] https://www.rbi.org.in/scripts/BS_SpeechesView.aspx?Id=310

[4] https://www.rbi.org.in/Scripts/NotificationUser.aspx?Id=11941&Mode=0

Our write up & FAQs on the framework may be viewed here: http://vinodkothari.com/2020/08/resolution-framework-for-covid-19-related-stress-resfracors/

http://vinodkothari.com/2020/09/faqs-on-resolution-of-loan-accounts-under-covid-19-stress/

[5] https://rbidocs.rbi.org.in/rdocs/Publications/PDFs/58TB5A66F26A72F460687373406F1D51C43.PDF

[6] https://www.rbi.org.in/Scripts/PublicationReportDetails.aspx?UrlPage=&ID=957

[7] https://www.rbi.org.in/Scripts/PublicationReportDetails.aspx?UrlPage=&ID=924

[8] https://www.financialexpress.com/industry/banking-finance/sbi-to-shift-to-cash-flow-based-lending-by-april-2020/1797095/

ARCs and Insolvency Resolution Plans – The Enigma of Equity vs Debt

/0 Comments/in Insolvency and Bankruptcy, Resolution, SARFAESI /by Vinod Kothari Consultants– By Sikha Bansal (resolution@vinodkothari.com)

This article has also been published in IndiaCorpLaw Blog, the same can be viewed here

A regulatory framework for asset reconstruction companies (ARCs) was introduced in India through the Securitisation and Reconstruction of Financial Assets and Enforcement of Security Interest Act, 2002 (SARFAESI Act). This intended to put in place a system for clearing up non-performing assets (NPAs) from the books of banks and financial institutions. Over a decade later, the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016 (IBC) was introduced with the objective of reorganisation and resolution of insolvent entities.

Although the common goal of both these legislation seems to be the cleaning or reconstruction of bad loan portfolios, it is important to understand the difference between the basic premises of these two laws: while the SARFAESI Act deals with ‘recovery’ and is more of a ‘class’ remedy, the IBC is about ‘resolution’ and intended to constitute a collective process. Given a common set of stakeholders involved under both these laws, there remains an obvious possibility of overlaps or inconsistencies. Read more →

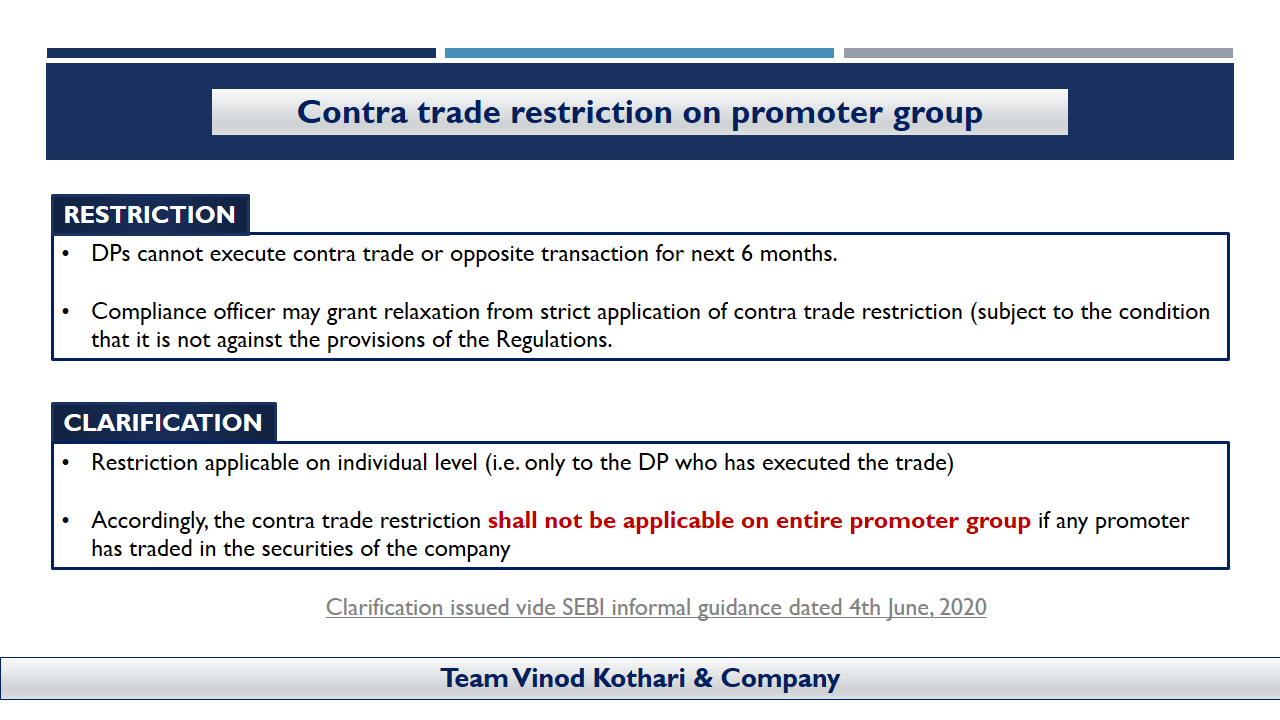

Contra trade restrictions on promoter group

/0 Comments/in Corporate Laws, SEBI /by Vinod Kothari ConsultantsLink to Informal Guidance by SEBI – https://www.sebi.gov.in/sebi_data/commondocs/sep-2020/SEBI%20let%20Raghav%20IG_p.pdf

RBI refines the role of the Compliance-Man of a Bank

/0 Comments/in Banking Regulations, Financial Services, RBI /by Vinod Kothari ConsultantsNotifies new provisions relating to Compliance Functions in Banks and lays down Role of CCO.

By:

Shaivi Bhamaria | Associate

Aanchal Kaur Nagpal | Executive

Introduction

The recent debacles in banking/shadow banking sector have led to regulatory concerns, which are reflected in recent moves of the RBI. While development of a robust “compliance culture” has always been a point of emphasis, RBI in its Discussion Paper on “Governance in Commercial Banks in India’[1] [‘Governance Paper’] dated 11th June 2020 has dealt extensively with the essentials of compliance function in banks. The Governance Paper, while referring to extant norms pertaining to the compliance function in banks, viz. RBI circulars on compliance function issued in 2007[2] [‘2007 circular’] and 2015[3] [‘2015 circular’], placed certain improvement points.

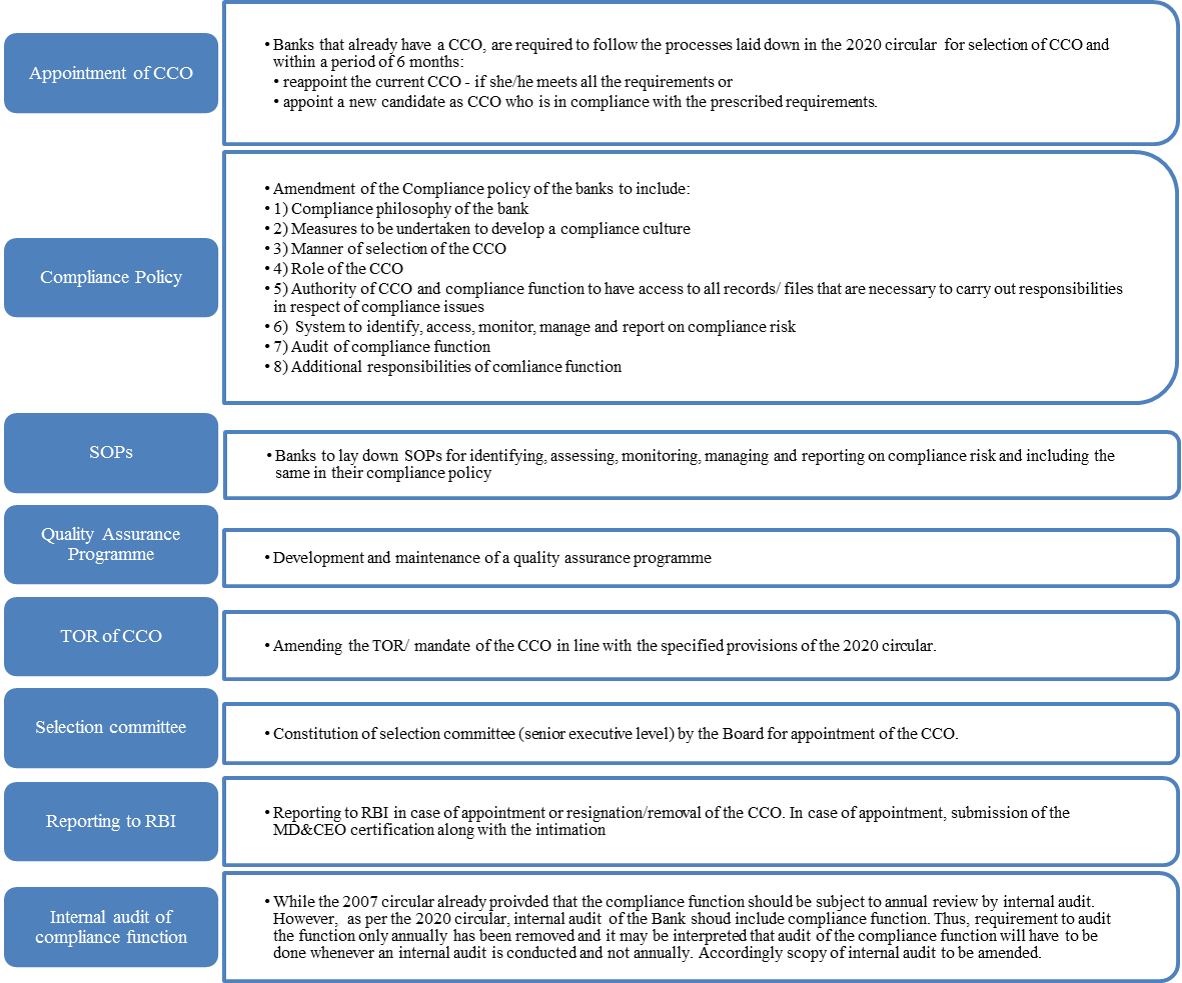

In furtherance of the above, RBI has come up with a circular on ‘Compliance functions in banks and Role of Chief Compliance Officer’ [‘2020 Circular’] dated 11th September, 2020[4], these new guidelines are supplementary to the 2007 and 2015 circulars and have to be read in conformity with the same. However, in case of or any common areas of guidance, the new circular must be followed. Along with defining the role of the Chief Compliance Officer [‘CCO’], they also introduce additional provisions to be included in the compliance policy of the Bank in an effort to broaden and streamline the processes used in the compliance function.

Generally, in compliance function is seen as being limited to laying down statutory norms, however, the importance of an effective compliance function is not unknown. The same becomes all-the-more paramount in case of banks considering the critical role they play in public interest and in the economy at large. For a robust compliance system in Banks, an independent and efficient compliance function becomes almost indispensable. The effectiveness of such a compliance function is directly attributable to the CCO of the Bank.

Need for the circular

The compliance function in banks is monitored by guidelines specified by the 2007 and 2015 circular. These guidelines are consistent with the report issued by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS Report)[5] in April, 2005.

While these guidelines specify a number of functions to be performed by the CCO, no specific instructions for his appointment have been specified. This led to banks following varied practices according to their own tailor-made standards thus defeating the entire purpose of a CCO. Owing to this, RBI has vide the 2020 circular issued guidelines on the role of a CCO, in order to bring uniformity and to do justice to the appointment of a CCO in a bank.

Background of CCOs

The designation of a CCO was first introduced by RBI in August, 1992 in accordance with the recommendations of the Ghosh Committee on Frauds and Malpractices in Banks. After almost 15 years, RBI introduced elaborate guidelines on compliance function and compliance officer in the form of the 2007 circular which was in line with the BCBS report.

According to the BCBS report:

‘Each bank should have an executive or senior staff member with overall responsibility for co-ordinating the identification and management of the bank’s compliance risk and for supervising the activities of other compliance function staff. This paper uses the title “head of compliance” to describe this position’.

Who is a CCO and how is he different from other compliance officials?

The requirement of an individual overseeing regulatory compliance is not unique to the banking sector. There are various other laws that the provide for the appointment of a compliance officer. However, there is a significant difference in the role which a CCO is expected to play. The domain of CCO is not limited to any particular law or its ancillaries, rather, it is all pervasive. He is not only responsible for heading the compliance function, but also overseeing the entire compliance risk[6] in banks.

Role of a CCO in a Bank:

The predominant role of a CCO is to head the compliance function in a Bank. The 2007 circular lays down the following mandate of a CCO:

- overall responsibility for coordinating the identification and management of the bank’s compliance risk and supervising the activities of other compliance function staff.

- assisting the top management in managing effectively the compliance risks faced by the bank.

- nodal point of contact between the bank and the RBI

- approving compliance manuals for various functions in a bank

- report findings of investigation of various departments of the bank such as at frequent intervals,

- participate in the quarterly informal discussions held with RBI.

- putting up a monthly report on the position of compliance risk to the senior management/CEO.

- the audit function should keep the Head of compliance informed of audit findings related to compliance.

The 2020 circular adds additional the following responsibilities on the CCO:

- Design and maintenance of compliance framework,

- Training on regulatory and conduct risks,

- Effective communication of compliance expectations

Selection and Appointment of CCO:

The 2007 circular is ambiguous on the qualifications, roles and responsibilities of the CCO. In certain places the CCO was referred to as the Chief Compliance officer and some places where the words compliance officer is used. This led to difficulty in the interpretation of aspects revolving around a CCO. However, the new circular gives a clear picture of the expectation of RBI from banks in respect of a CCO. The same has been listed below:

| Basis | 2020 circular | 2007 circular |

| Tenure | Minimum fixed tenure of not less than 3 years | The Compliance Officer should be appointed for a fixed tenure |

| Eligibility Criteria for appointment as CCO | The CCO should be the senior executive of the bank, preferably in the rank of a General Manager or an equivalent position (not below two levels from the CEO). | The compliance department should have an executive or senior staff member of the cadre not less than in the rank of DGM or equivalent designated as Group Compliance Officer or Head of Compliance. |

| Age | 55 years | No provision |

| Experience | Overall experience of at least 15 years in the banking or financial services, out of which minimum 5 years shall be in the Audit / Finance / Compliance / Legal / Risk Management functions. | No provision

|

| Skills | Good understanding of industry and risk management, knowledge of regulations, legal framework and sensitivity to supervisors’ expectations | No provision |

| Stature | The CCO shall have the ability to independently exercise judgement. He should have the freedom and sufficient authority to interact with regulators/supervisors directly and ensure compliance | No provision |

| Additional condition | No vigilance case or adverse observation from RBI, shall be pending against the candidate identified for appointment as the CCO. | No provision |

| Selection* | 1. A well-defined selection process to be established

2. The Board must be required to constitute a selection committee consisting of senior executives 3. The CCO shall be appointed based on the recommendations of the selection committee. 4. The selection committee must recommend the names of candidates suitable for the post as per the rank in order of merit. 5. Board to take final decision in the appointment of the CCO. |

No provision |

| Review of performance appraisal | The performance appraisal of the CCO should be reviewed by the Board/ACB | No provision |

| Reporting lines | The CCO will have direct reporting lines to the following:

1. MD & CEO and/or 2. Board or Audit Committee |

No provision |

| Additional reporting | In case the CCO reports to the MD & CEO, the Audit Committee of the Board is required to meet the CCO quarterly on one-to-one basis, without the presence of the senior management including MD & CEO. | No provision |

| Reporting to RBI | 1. Prior intimation is to be given to the RBI in case of appointment, premature transfer/removal of the CCO.

2. A detailed profile of the candidate along with the fit and proper certification by the MD & CEO of the bank to be submitted along with the intimation, confirming that the person meets the supervisory requirements, and detailed rationale for changes. |

No provision |

| Prohibitions on the CCO | 1. Prohibition on having reporting relationship with business verticals

2. Prohibition on giving business targets to CCO 3. Prohibition to become a member of any committee which brings the role of a CCO in conflict with responsibility as member of the committee. Further, the CCO cannot be a member of any committee dealing with purchases / sanctions. In case the CCO is member of such committees, he may play only an advisory role. |

No provision |

*The Governance paper had proposed that the Risk Management Committee of the Board will be responsible for selection, oversight of performance including performance appraisals and dismissal of a CCO. Further, any premature removal of the CCO will require with prior board approval. [Para 9(6)] However, the 2020 circular goes one step further by requiring a selection committee for selection of a CCO.

Dual Hatting

Prohibition of dual hatting is already applicable on the Chief Risk Officer (‘CRO’) of a bank. The same has also been implemented in case the of a CCO.

Hence, the CCO cannot be given any responsibility which gives rise to any conflict of interest, especially the role relating to business. However, roles where there is no direct conflict of interest for instance, anti-money laundering officer, etc. can be performed by the CCO. In such cases, the principle of proportionality in terms of bank’s size, complexity, risk management strategy and structures should justify such dual role. [para 2.11 of the 2020 circular]

Role of the Board in the Compliance function

Role of the Board

The bank’s Board of Directors are overall responsible for overseeing the effective management of the bank’s compliance function and compliance risk.

Role of MD & CEO

The MD & CEO is required to ensure the presence of independent compliance function and adherence to the compliance policy of the bank.

Authority:

The CCO and compliance function shall have the authority to communicate with any staff member and have access to all records or files that are necessary to enable him/her to carry out entrusted responsibilities in respect of compliance issues.

Compliance policy and its contents

The 2007 circular required banks to formulate a Compliance Policy, outlining the role and set up of the Compliance Department.

The 2020 circular has laid down additional points that must be covered by the Compliance Policy. In some aspects, the 2020 circular provides further measures to be taken by banks whereas in some aspects, fresh points have been introduced to be covered in the compliance policy, these have been highlighted below:

1. Compliance philosophy: The policy must highlight the compliance philosophy and expectations on compliance culture covering:

- tone from the top,

- accountability,

- incentive structure

- Effective communication and Challenges thereof

2. Structure of the compliance function: The structure and role of the compliance function and the role of CCO must be laid down in the policy

3. Management of compliance risk: The policy should lay down the processes for identifying, assessing, monitoring, managing and reporting on compliance risk throughout the bank.

The same should adequately reflect the size, complexity and compliance risk profile of the bank, expectations on ensuring compliance to all applicable statutory provisions, rules and regulations, various codes of conducts and the bank’s own internal rules, policies and procedures and must create a disincentive structure for compliance breaches.

4. Focus Areas: The policy should lay special thrust on:

- building up compliance culture;

- vetting of the quality of supervisory / regulatory compliance reports to RBI by the top executives, non-executive Chairman / Chairman and ACB of the bank, as the case may be.

5. Review of the policy: The policy should be reviewed at least once a year

Quality assurance of compliance function

Vide the 2020 circular, RBI has introduced the concept of quality assurance of the compliance function Banks are required to develop and maintain a quality assurance and improvement program covering all aspects of the compliance function.

The quality assurance and improvement program should be subject to independent external review at least once in 3 years. Banks must include in their Compliance Policy provisions relating to quality assurance.

Thus, this would ensure that the compliance function of a bank is not just a bunch of mundane and outdated systems but is improved and updated according to the dynamic nature of the regulatory environment of a bank.

Responsibilities of the compliance function

In addition to the role of the compliance function under the compliance process and procedure as laid down in the 2007 the 2020 circular has laid down the below mentioned duties and responsibilities of the compliance function:

- To apprise the Board and senior management on regulations, rules and standards and any further developments.

- To provide clarification on any compliance related issues.

- To conduct assessment of the compliance risk (at least once a year) and to develop a risk-oriented activity plan for compliance assessment. The activity plan should be submitted to the ACB for approval and be made available to the internal audit.

- To report promptly to the Board/ Audit Committee/ MD & CEO about any major changes / observations relating to the compliance risk.

- To periodically report on compliance failures/breaches to the Board/ACB and circulating to the concerned functional heads.

- To monitor and periodically test compliance by performing sufficient and representative compliance testing. The results of the compliance testing should be placed before the Board/Audit Committee/MD & CEO.

- To examine sustenance of compliance as an integral part of compliance testing and annual compliance assessment exercise.

- To ensure compliance of Supervisory observations made by RBI and/or any other directions in both letter and spirit in a time bound and sustainable manner.

Actionables by Banks:

Links to related write ups –

- RBI proposes to strengthen governance in banks

- RBI proposes to consolidate guidelines on governance for commercial banks

- RBI guidelines on governance in commercial banks

[1] https://www.rbi.org.in/Scripts/BS_PressReleaseDisplay.aspx?prid=49937

[2] https://www.rbi.org.in/Scripts/NotificationUser.aspx?Id=3433&Mode=0

[3] https://www.rbi.org.in/Scripts/NotificationUser.aspx?Id=9598&Mode=0

[4] https://www.rbi.org.in/Scripts/NotificationUser.aspx?Id=11962&Mode=0

[5] https://www.bis.org/publ/bcbs113.pdf

[6] According to BCBS report, compliance risk is the risk of legal or regulatory sanctions, material financial loss, or loss to reputation a bank may suffer as a result of its failure to comply with laws, regulations, rules, related self-regulatory organization standards, and codes of conduct applicable to its banking activities”

Liability Acknowledgment & Limitation Period for IBC Applications

/0 Comments/in Insolvency and Bankruptcy /by Vinod Kothari ConsultantsThis article has also been published in the LawStreetIndia blog – http://www.lawstreetindia.com/experts/column?sid=466 Liability Acknowledgment & Limitation Period for IBC Applications – Deciphering the Enigma -Sikha Bansal (resolution@vinodkothari.com) The applicability of the Limitation Act, 1963 (Limitation Act) to the applications under the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016 (Code) has been settled long back, after a series of […]