Broken Pledge? Apex Court reviews the law on pledges

By Vinod Kothari, Managing Partner, Sikha Bansal, Partner and Shraddha Shivani, Executive | corplaw@vinodkothari.com

The Supreme Court ruling in PTC India Financial Services Limited v. Venkateshwar Kari and Another is significant in many ways – not that it categorically rewrites the law of pledges which is settled with 150 years of the statute[1] and even longer history of rulings, but it surely refreshes one of the predicaments of a pledge. Importantly, since most of the pledges of securities currently are in the dematerialised format, it brings out a very important distinction between the meaning of ‘beneficial owner’ under the Depository law, and the right of the pledgee (a.k.a. pawnee or security interest holder) to cause the sale in terms of the rights arising under the pledge. Also, very importantly, the SC dwells upon the essential principle of equity of redemption in pledges and renders void any provision in the pledge agreement which allows the pledgee to make a sale of the pledged article without notice to the pledgor, or to forfeit the pledged article and convert the same as pledgee’s own property. There are also observations in the ruling that seem to give an indefinite time to the pledgee for the sale of the pledged property – this is a point that this article discusses at some length.

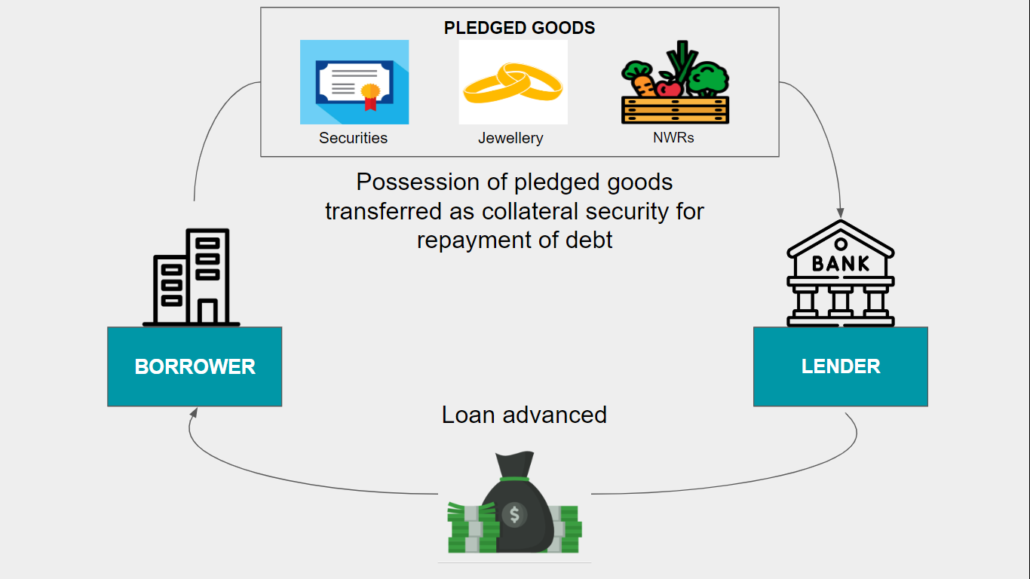

Pledges are quite common in the world of finance. Some of the important applications of pledges are:

- It is very common practice for banks and lenders to require promoters to pledge their shareholding in the promoted company. SEBI regulation[2] mandates disclosure of pledge of their holdings by the promoters to stock exchanges. As per recent data of NSE, the extent of promoters’ holding, which is pledged, as a percentage of total promoters’ holding, is about 8.59%[3] on average.

- The entire business of loan against shares works on the basis of pledges. The volume of loan against shares was ₹6,112 crore at the end of April 2022[4].

- The entire business of gold loans is based on pledge of gold jewellery and articles which stands at approximately ₹25,000 crore.[5]

- The concept of margin-based trading where investors pledge their portfolio stocks with the pledgor in return for a collateral margin which can then be used for further trading or investing, is fairly common.

- Banks and other financial entities pledge their holdings of corporate bonds or other securities for borrowing from the RBI.

- Pledge of agricultural produce and produce kept in warehouses, by way of warehouse receipts, is also very common.

Thus, the use of pledge is ubiquitous in the business of banking and fund-based finance.

In this write-up, we discuss some of the important points on the law of pledges arising out of the ruling[6]. This article has been structured as follows:

- The essential law of pledge

- Manner of sale of pledged article upon default of the borrower and equity of redemption

- Is there a time limit for sale by the pledgee?

- What value goes to the credit of the borrower upon sale, and until sale?

- Can the pledgee retain pledged goods and make them part of his own property?

- Manner of selling in case of demat shares, and aligning provisions of Depositories law

A. The essential law of pledge

Governing law

A pledge is a specie of bailment. The bailment of goods as security for payment of a debt or performance of a promise is called a “pledge”. The primary purpose of pledge is to put the goods pledged in the power of the pawnee to reimburse himself for the money advanced, when on becoming due it remains unpaid, by selling the goods after serving the pawnor with a due notice.

Provisions relating to contracts of bailment have been provided in Chapter IX of the Indian Contract Act and pledges specifically have been dealt with in sections 172 to 179. There is no standard format of a pledge and the terms of a pledge agreement may be different in different circumstances. A term mutually agreed by the parties is valid as long as it is not contrary to or inconsistent with any provision of the Contract Act.

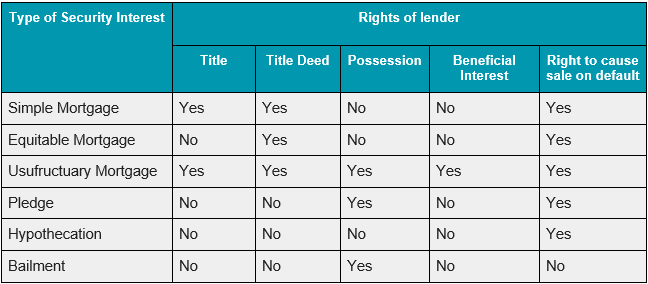

Also, pledge is one type of security interest. Here we have a comparative view on different kinds of security interests[7]:

Essential features of a pledge:

Delivery

The Supreme Court in Lallan Prasad v. Rahmat Ali and Another had recognized actual or constructive delivery of pawn i.e. the pledged goods to the pawnee as an essential ingredient of pledge. The same was recognized in Morvi Mercantile Bank Ltd. v. Union of India by drawing conclusion from English law whereby it was held that it is essential for the creation of a pledge that there should be a delivery of the goods contained therein.

Special property

In Lallan Prasad (supra), the SC held, “a pawnee has only a special property in the pledge but the general property therein remains in the pawner and wholly reverts to him on discharge of the debt. A pawn therefore is a security, where, by contract a deposit of goods is made as security for a debt. The right to property vests in the pledgee only so far as is necessary to secure the debt. In this sense a pawn or pledge is an intermediate between a simple lien and a mortgage which wholly passes the property in the thing conveyed.”

The Supreme Court in Central Bank Of India v. Siriguppa Sugars & Chemicals Ltd. & Ors referenced to its ruling in Karnataka Pawnbroker’s Association and others v. State of Karnataka and others where it held that-

“It cannot be and it is not disputed that the pawnbroker has special property rights in the goods pledged, a right higher than a mere right of detention of goods but a right lesser than general property right in the goods. To put it differently, the pawnor at the time of the pledge not only transfers to the pawnee, the special right in the pledge but also passes on his right to transfer the general property right in the pledge in the event of the pledge remaining unredeemed resulting in the sale of the pledge by public auction through an approved auctioneer. The position being what is stated above, the natural consequence will be that it is the pawnee who holds not only the absolute special property right in the pledge but also the conditional general property interest in the pledge, the condition being that he can pass on that general property only in the event of the pledge being brought to sale by public auction in accordance with the Act and the Rules framed thereunder.”

The Andhra High Court in Shatzadi Begum Saheba And Ors. vs Girdharilal Sanghi And Ors held that-

“As observed in Sanjiva Row’s commentaries on Indian Contract Act “a ‘pledge’ is delivery of goods by the pledgor to the pledgee by way of security upon a contract that they shall when the debt is paid or the promise is performed be returned or otherwise disposed of according to the directions of the pledgor…. A pledgee does not have the right of ownership, though he has the right of possession, but not the right of enjoyment; a pledgee has the right of disposition which is limited to disposition of pledgee’s rights only and of a sale only after notice and subject to certain limitation.”

In the case of Balkrishan Gupta And Ors v. Swadeshi Polytex Ltd the Supreme Court observed that even after a pledge is enforced, the legal title to the goods pledged would not vest in the pawnee. The pawnee has only a special property. A pawnee has no right of foreclosure since he never had absolute ownership at law and his equitable title cannot exceed what is specifically granted by law. The right to property vests in the pledged goods only so far as is necessary to secure the debt. This principle has been cemented by the courts in various cases.

Given the above, it would lead to a question as to whether the pledgee, while retaining the special property in the pledged goods, is entitled to the usufructs or accretions arising out of such property. We have discussed this under the heading ‘Who enjoys the rights attached to pledged securities?’.

B. Manner of sale of pledged article upon default of the borrower and equity of redemption

Pledgee’s right to sell

Section 176 of the Contract Act empowers the pawnee to bring a suit against the pawnor upon the unfulfilled debt or promise, and retain the goods pledge as a collateral security, or sell the article pledged after giving the pawnor a reasonable notice of the intended sale.

However, such right to sell should be exercised in compliance with the provisions of section 176. The requirement of a reasonable notice is mandatory and cannot be curtailed by a contrary provision in the contract. This has been upheld in an array of rulings, including in PTC India (supra), which observes,

“where the Contract Act prescribes a particular term that is binding, the statutory mandate must be followed by the parties. Neither party can contract out of it. Otherwise, the legislative command that the statute imposes would be violated with immunity by merely incorporating waiver as a contractual term, depriving the frailer party of the benefit of the legal protection. A condition prescribed to protect and benefit the public cannot be dispensed with when it lays down a rule of public policy.”

The following excerpts from Calcutta High Court in Co-Operative Hindusthan Bank v. Surendra Nath Dey And Ors may also be seen:

“Section 176, Contract Act, unlike some other sections, e.g., Sections 163, 171 and 174 does not contain a saving clause in respect of special contracts contrary to its express terms. The section gives the pawnor the right to sell only as an alternative to the right to have his remedy by suit. Besides Section 177 gives the pawnor a right to redeem even after the stipulated time for payment and before the sale. In our opinion in view of the wording of Section 176 as compared with the wording of the other sections of the Act, to which we have referred and also in view of the right which Section 177 gives to the pawnor and in order that the provision of that section may not be made nugatory, the proper interpretation to put on Section 176 is to hold that notwithstanding any contract to the contrary notice has to be given.”

If the sale is not in conformity with the provisions, the pledgor’s right of redemption is not extinguished. Further, in case of a sale which does not conform to the requirements, “the transferee does not acquire anything more than the right, title and interest of the pledgee which is to retain the goods as a pledge till the debt is paid off”. As such, if the pledgee has transferred the shares, he is entitled to call upon the transferee for the same. Therefore, in such cases, the pledgor’s right of redemption overrides the usual exemption available to a bona fide transferee. There is an absence of any provision in section 176 of the Contract Act in favour of an innocent purchaser, based on the doctrine of nemo dat quod non habet. See Nabha Investment Pvt. Ltd. v. Harmishan Dass Lukhmi Dass.

Pledgor’s Right of redemption

The right to sue on the debt assumes that the pledgee is in a position to redeliver the goods on the payment of the debt but if he has put himself in a position where he is not in a position to redeliver the goods he cannot obtain a decree.

Once the pledgor has received notice of the intention of the pledgee to sell the pledged goods, he may still redeem such pledged goods at any time before the actual sale to a third party by virtue of section 177. In such cases, the pledgor must pay expenses incurred by the pledgee due to his default in addition to the debt amount.

As discussed in PTC India (supra), sale to self (as discussed below) would be a case of conversion and not ‘actual sale’, and would thus, not affect the pawnor’s right of redemption. The ruling, however, draws carve-outs for demat listed securities – see at the end of this article.

Further, as discussed above, where the sale is not in conformity with the provisions of section 176, the pledgor’s right of redemption remains alive. The only exception that the SC has made is in case of listed shares, where the right of the pawner to claim shares of listed securities sold without adherence to the requirements of prior notice, is not available in case of a sale made to an innocent third party. However, it is clear from the ruling that this exception was made from the view of practicality and ensuring the certitude of listed shares which may seamlessly keep changing hands in nanoseconds.

Sale to self by pledgee

It is important to note here that sale of pledged goods by the pledgee to himself does not extinguish pledgor’s right of redemption. In PTC India (supra), the Supreme Court held that sale to self is a case of conversion[8], and not ‘actual sale’. As such, the pawnor’s right of redemption remains till the actual sale of goods which must be in conformity with section 176.

In GTL Limited v. IFCI Ltd. & Ors, it was clearly held that –

“the foreclosed shares or 17,63,68,219 shares appropriated by the defendant to itself is done in contravention to the law of pledge as no such right to foreclosure is available to the pledge. His equitable title cannot exceed what has been permissible under the law. Accordingly, the defendant no. 1 is still a pledgee of the said appropriated shares. . . The stipulation in agreement giving absolute right to sell after the invocation of pledge is contrary to the law and thus prima facie illegal and cannot come in the way of effecting the valid pledge.”

However, such sale to self does not entitle the pawnor to have the goods back without repayment. In Neikram Dobay v. Bank of Bengal the Privy Council held that the sale of goods by pawnee to himself, although unauthorised, does not entitle the pawnor to have the goods back without the repayment of loan.

University of Pennsylvania Law Review, February 1912 stated that “it is unlawful for the pledgee to directly or indirectly purchase at his own sale, as he stands in a fiduciary relation to the pledge, and like a trustee, he is not permitted to buy in property so committed to his charge. Hisduty to the pledgor is inconsistent with his interest as a purchaser. His duty to the pledgor is to get the highest price which the property will bring and his interest as a purchaser is to get it as cheaply as possible. However, a purchase by the pledgee does not of itself amount to a conversion, as the pledgee is still in a position to fulfill his contract.”

A similar view was expressed by Marquette Law Review in 1940 stating that generally, in the absence of an express permission, a purchase and retention of the collateral by pledgee is not held a conversion. The transaction is voidable and thus the pledgor may either ratify or repudiate.

In Ramdeyal Prasad v. Sayed Hasan, the Patna High Court has held that the sale by the pawnee to himself of the securities pledged is void; it does not put an end to the contract of the pledge to entitle the pawnor to recover the goods without payment of the amount thereby secured, nor does it entitle the pawnor to damages. The pawnor is bound by the resale duly effected by the pawnee to third persons. However, where the pawnee has erroneously represented to the pawnor before such resales that the securities have been sold and, therefore, no longer available for redemption, the pawnee becomes liable for the value as conversion.

Therefore, the right of foreclosure has not been provided to the pledgee by law; as such, the same cannot be provided by the contract too. Any stipulation to that effect in the contract, as indicated in GTL Limited (supra), is invalid and in contravention of law.

However, as seen in practice, companies do execute power of attorney in favour of the pledgee at the time of entering into loan contracts. This may bypass the prohibition on selling of pledged goods by pledgee to himself. The Supreme Court in PTC India ruling has prescribed an absolute prohibition on transferring the ownership rights in pledged assets to the pledgee whether directly or indirectly. In our view, this would bring the practice of indirectly transferring pledged goods to the pledgee within its ambit. Obviously, the power of attorney could not have been an independent power, more so when it allows the attorney to retain the sale proceeds. This would change the long established mechanisms under which the financial market functions and would have far reaching effects. Thus, many regulatory provisions would have to be re-examined.

At this point, it may be noted that there is a difference in being registered as a ‘beneficial owner’ under the Depositories Act, and selling the shares to self. The distinction, as discussed later in this article, has been clearly brought out by the SC in PTC India, saying that there is no conflict between the provisions of the Depositories Act and the Contract Act, and the pledgee becoming ‘beneficial owner’ does not amount to sale to self or sale at all, but is merely a condition precedent to exercise the right of sale in terms of the Contract Act.

Proceeds of sale

While the pawnor remains liable for the balance amount in case the sale proceeds fall short of the amount owed to the pawnee, the pawnor is entitled to the surplus arising out of the sale of the pledged goods, as explicitly covered under section 176 of the Contract Act.

In Lallan Prasad (supra), SC clearly states,

“If the pawnee sells, he must appropriate the proceeds of the sale towards the pawner’s debt, for, the sale proceeds are the pawner’s monies to be so applied and the pawnee must pay to the pawner any surplus after satisfying the debt. The pawnee’s right of sale is derived from an implied authority from the pawner and such a sale is for the benefit of both the parties.”

In Sultan and Ors v. Firm of Rampratap Kannyalal the Andhra High Court held that when a pledgee sells the pledged goods, he does so by virtue and to the extent of the pledger’s ownership, and not with a new title of his own. He must take care that the sale is a provident sale and not sell more than is reasonably sufficient to pay off the debt. He only holds possession for the purpose of securing himself the advance which he has made and cannot use the goods as his own.

The proceeds from sale of the pledged goods is the pledgor’s property out of which the pledgee may only appropriate the amount due to him and return any surplus to the pledgor. However, if the proceeds of such sale are less than the amount due in respect of the debt, the pawnor is still liable to pay the balance due.’

C. Is there a time limit for sale by the pledgee?

Notice of sale

The Contract Act allows the pledgee to sell off the pleaded goods and secure his debt after giving a reasonable notice of his intention to do so to the pledgor. Such notice does not require specification of the date, time and place of sale. The Act itself also does not specify any time period within which the pledgee must mandatorily cause disposal of the pledged goods.

It has been held by the Bombay High Court in The Official Assignee v. Madholal Sindhu that a notice must be given in all cases of pledge, even when the instrument of pledge itself contains an unconditional power of sale. It is not open to parties to contract themselves out of the provisions of section 176 of the Contract Act.

Time for sale

The Kerala High Court in Syndicate Bank v. C.H.Muhammed held that a pledgee is not compelled by law to sell the pledged goods, in regard to which his right of sale has accrued under the law, within any particular time. In fact, the Madras High Court in K.M. Hidayathulla v. Bank Of India held that the pledgee may resort to sale of pledged assets to secure his debt even after the prescribed period for filing of suits under the Limitation Act, 1963 has expired.

The National Company Law Appellate Tribunal in PTC India Financial Services Ltd v. Mr. Venkateswarlu Kari & Ors had also held that while the pawnee has a right to sell the goods after giving notice to the pawnor, he is not bound to sell at any particular time. A pawnee, unless he so agrees, cannot be compelled by the pawnor to sell goods. The power of sale conferred on the pawnee is expressly for his benefit, and it is his sole discretion to exercise the power of sale or otherwise. If the pawnee does not exercise that discretion, no blame can be put on him. Even where the value of the goods deteriorates due to time, no relief can be granted to the pawnor against the pawnee as the pawnor is legally bound to clear the debt and obtain possession of the pawned goods.

Similarly, in Hulas Kunwar v. Allahabad Bank Ltd, the Calcutta High Court held that a pledgee is within its rights to sell the pledged goods “as and when opportunity offers” meaning whenever market conditions are most favourable.

This was later reiterated by the Supreme Court in Vimal Chandra Grover v. Bank Of India where it was held that the pledgee was under no obligation whatsoever to release the shares which were in its possession and could not be compelled in law to sell any of the pledged shares.

However, section 161 of the Contract Act also provides that where to the default of the bailee, the goods are not returned, delivered or tendered at the proper time, he is responsible to the bailor for any loss, destruction or deterioration of the goods from that time.

Accordingly, the pledgee would not be free from consequences where it can be proved that the pledgor has suffered loss due to the pledgee’s default on account of delayed sales. For instance, in the Vimal Chandra case (supra), the failure of the pledgee bank for not selling the pledged goods after having agreed to do so had been held as negligence in service under the Consumer Protection Act, 1986.The Court had then awarded compensation to the pledgor on account of damages suffered along with interest at the rate of 11% from the year in which the pledgee had committed default and at an even higher rate of interest from the date of judgement.

In Shrikant G. Mantri v. Punjab National Bank, although the question as to delayed sale of shares by the pledgee was raised (when the market value of the shares was low), however, the case revolved around determination of whether the complainant (a stock-broker) was a consumer or not, and the question pertaining to delayed sale was not at all discussed by SC.

The question of whether the pledgee should have to conform to a specified time limit within which to dispose of the pledged goods remains unsettled. It is quite okay to say that the pledgee simply has to notify his intent of selling the goods, after invocation or along with that, and that he is not bound to exactly indicate the time of sale. There are many Indian rulings on this[9]. However, almost every ruling has emphasised on the “reasonable notice before sale”. Can a notice of invocation after default, along with notice of intent to sell, be given, say, in month 1, and the lender may continue to wait for an opportune time to sell, say, till month 24? It is important to note that the borrower continues to be liable to an overdue rate of interest, which is usually substantially higher than the normal rate of interest. Can the lender be justified in exposing the borrower to the burden of not adjusting the sale value of the pledged goods by effecting the sale, unless there are strong reasons to delay the sale? It surely does not seem appropriate to say that the lender waits for an opportune time to cause the sale, as the lender’s interest is simply that of a secured creditor and not that of a proprietor. While it is possible to argue that the lender’s realisation of security interest is affected by the price of the pledged article, and therefore, the timing is important, but a lender is not a speculator who can take direcional calls on the prices of pledged goods; even more so when a lender is a financial institution.

In the authors’ view, having given the notice of intent to sell, the lender should proceed to sell expeditiously.

D. What value goes to the credit of the borrower upon sale, and until sale?

After Invocation

It is clear from the various rulings cited above that there is no credit to the account of the borrower merely on the fact of invocation. In case of securities, even the transfer of beneficial ownership in the records of the Depository Participant does not amount to transfer of any beneficial interest in law. Hence, there is no credit to the account of the borrower upon invocation.

It may be intriguing to ask, what, then is the impact of invocation? The pledgee was entitled to retention of possession on the day the pledge was created. The pledgee is entitled to retention, upon invocation of the pledge as well. In essence, what is the difference in the rights of the pledgee before and after invocation?

In the authors’ view, the pledgee had twin rights under the pledge – (a) to sue for money and not enforce the pledge; or (b) to enforce the pledge, and sue for the balance, if any. Once he has invoked the pledge, he has chosen the second option, and therefore, cannot claim repayment of the full debt.

In Haridas Mundra vs National And Grindlays Bank Ltd, it was the view of the Calcutta High Court that the right to sell and the right to sue are not mutually exclusive and the pledgee can exercise both rights at the same time.

However, later the Supreme Court in Lallan Prasad vs Rahmat Ali & Another held that the pledgee would not be entitled to a decree against the pledgor and also to retain the pledged goods in his custody.

This itself becomes a strong reason for the lender to consider concluding the sale soon after invocation.

Upon Sale

The proceeds out of sale of the pledged property has to be first utilized for the repayment of the pledgee’s debt in full including interest and other expenses. The usual appropriation rules may have to be applied for this. Any surplus remaining after the repayment is to be returned to the pledgor. However, where such sale does not adequately cover the debt obligation, the pledgor would continue to remain liable to the pledgee for the amount due by him.

It is quite a common practice for lenders to invoke the pledge, and keep the pledged goods with the lender. Our article on the issue provides guidance on this.

E. Can the pledgee retain pledged goods and make them part of his own property?

Right to retain

Section 176 of the Contract Act provides that upon default by the pledgor, pawnee may retain the pledged goods as a collateral security. It has been clarified that pawnee’s right to retain and sell the pledged goods stretches to the right to retain and sell any increase and accumulations to the pledged goods. Section 173 further allows the pawnee to retain the goods pledged for the interest of the debt, and all necessary expenses incurred by him in respect of the possession or for the preservation of the goods pledged.

Section 174 provides for a restriction on the right to retain such pledged goods for any debt or promise other than the debt or promise for which they are pledged.

Right to sub-pledge

Section 179 of the Contract Act provides that where a person pledges goods in which he has only a limited interest, the pledge is valid to the extent of that interest.

It has been held in PTC India (supra) that a pawnee may assign or pledge his special property or interest in the goods.

The Bombay High Court in The Official Assignee of Bombay v. Madholal Sindhu and Others had referenced the judgement of Justice Mellor in Donald v. Suckling (1866) which read as follows-

“pledgee cannot confer upon any third person a better title or a greater interest than he possesses, yet, if nevertheless he does pledge the goods to a third person for a greater interest than he possesses, such an act does not annihilate the contract of pledge between himself and the pawnor; but that the transaction is simply inoperative as against the original pawnor, who upon tender of the sum secured immediately becomes entitled to the possession of the goods, and can recover in an action for any special damage which he may have sustained by. reason of the act of the pawnee in repledging the goods.”

Right to own

The pledgee owns the pledged goods as a collateral security however he does not have any proprietary right in the same. By this we mean that the pledgee does not gain the right of enjoyment of the pledged goods, he merely enjoys the right of possession and the right of disposition to a third party.

To emphasise upon the limited rights of a pledgee we may refer to Chitty on Contract, 27th edition which read as follows – “If the pledgee deals with the thing pledged in an unlawful manner, such as by sale before the time fixed for repayment of the debt, or by wrongfully claiming to be absolute owner of the thing, the contract of pledge is not determined and the pledgor cannot, without payment or tender of the debt, sue the pledgee for conversion. But if the pledgee “deals with it in a manner other than is allowed by law for the payment of his debt, then, insofar as by disposing of the reversionary interest of the pledgor he causes to the pledgor any difficulty in obtaining possession of the pledge on payment of the sum due, and thereby does him any real damage, he commits a legal wrong against the pledgor.”

The very fact that the pledgee has limited rights on the property, means that the pledgee is not entitled to enjoyment of or accretions on such property – see discussion later.

F. Manner of selling in case of demat shares, and aligning provisions of Depositories law and Securities Law

Governing law

In the case of shares not held in demat form, it was held by the Company Law Board in Maruti Udyog Ltd. v. Pentamedia Graphics Ltd it was held that “unlike other movable goods, in normal commercial practice, when shares are pledged with blank transfer forms, the pledgor has the option of retaining the shares without registering the transfer in his name or get the shares registered in his name. Both the practices are common. Registering the shares in the name of the pledgor does not in any way constitute a sale requiring notice to be given to the pledgor.”

Section 12 of the Depositories Act, 1996 provides for pledge or hypothecation of securities held in a depository but that is not to say that the Depositories Act alone governs the pledge and hypothecation of dematerialized securities. Section 28 clarifies that provisions of this Act shall be in addition to, and not in derogation of, any other law for the time being in force relating to the holding and transfer of securities.

Procedure

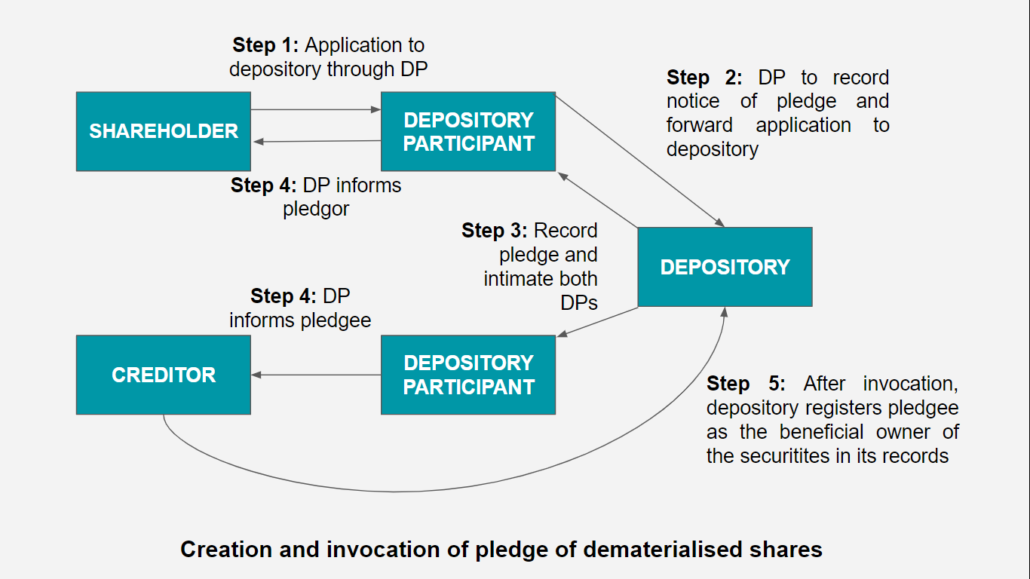

The manner in which a pledge or hypothecation on demat securities may be created has been detailed in Regulation 79 of the SEBI (Depositories and Participants) Regulations, 2018.

Contract Act and Securities Laws

A preliminary reading of the above regulation might give the impression that it has done away with the right of redemption of pledgor protected by section 177 of the Contract Act causing a contradiction between these Regulations and the Contract Act.

However, in the recent ruling of PTC India Financial Services Limited (supra) the Hon’ble Supreme Court has held that sections 176 and 177 of the Contract Act are not obliterated by the Depositories Act or the Depositories and Participants Regulations, insofar as they would equally apply to pawned dematerialised securities as they apply to other pawned goods.

Exercise of right by the pledgee to register himself as the beneficial owner of shares in the records of the depository is a necessary precondition for the pledgee to exercise his right to sell the security and secure his debt. Accordingly, it will not be treated as sale of the pledged securities.

Specifically concerning the equity of redemption, the Supreme Court held that the expression ‘actual sale’ used in Section 177 of the Contract Act should be read as ‘the sale by the pawnee to a third person made in accordance with the Depositories Act and applicable by-laws and rules’.

Special provision for listed securities

The Supreme Court also held that when it comes to listed dematerialised securities, the principle that the pawnor is entitled to redeem its security from the third party on the ground of not having received a reasonable notice under section 176 of the Contract Act, if applied, would materially impact certitude in the transaction in listed dematerialised securities. Pledgor’s right to redemption in such a case would make bona fide third party purchases made at arm’s length valuation vulnerable to challenge, causing a loss of investor confidence in open market operations.

To this extent, right to redemption against third parties when the pawnee does not give reasonable notice under Section 176 of the Contract Act, would not apply to listed dematerialised securities which are sold by the pawnee in accordance with the provisions of the Depositories Act, by-laws and rules.

It is important to note here that the act of such a sale without giving a reasonable notice to the pawnor is still in contravention of the Contract Act and the pledgor may still sue the pledgee for wrongful disposal of his goods.The pledgee’s obligation remains intact, It is only the pledgor’s right of redemption that is lost.

Who enjoys the rights attached to pledged securities

We know from the Contract Act and various rulings over the years that the pledgee is not entitled to enjoyment of the pledged goods. In the context of securities, such enjoyments would be in the form of right to attend meetings, right to vote, right to receive dividend and bonus shares, etc.

In GTL Limited v. IFCI Ltd. & Ors the Delhi High Court held, “the pawnee has only the right to retention of the goods till the time of realisation of debt and not the right to enjoying the same or forfeiture.”

The Delhi High Court in M.R. Dhawan v. Madan Mohan And Ors emphasised that as the pawner acquires only a special property in the pledged property, any accretion will therefore belong to the pawnor, in the absence of contract to the contrary –

“(13) It will, thus, be seen that the pawnee acquires a right, after notice, to dispose of the goods pledged. This amounts to his acquiring only a “special property” in the goods pledged. The B general property therein remains in the pawnor and wholly reverts to him on payment of the debt or performance of the promise. Any accretion in the shape of dividends, bonus or right shares, issued in respect of the pledged sharps will, therefore, be, in the absence of any contract to the contrary, the property of the pawnor.

(14) the contention of the learned counsel for the respondents that in in the case of a transfer of shares, the transferee becomes entitled to all the dividends declared after the contract of transfer and to the bonus or right shares, if any therefore, has no relevance; because in the case of a transfer which is a sale, general property is transferred to the buyer which does not happen in the case of a pledge. The general property having, thus, remained in the pawner, he remains entitled to all the dividends that may be declared on the shares and to the bonus and right shares that may be issued in respect of the shares pledged.”

However, it must be noted that any accretions on pledged goods may be used to cover the debt amount of the pledgee. In Standard Chartered Bank and another v. Custodian and another the Supreme Courthad held that “bonus shares, dividend and interest were accretions to the pledged stock and have to be regarded as forming part of the pledged property which could not be ordered to be handed over unless redemption takes place.”

In Halsbury’s Laws of England Vol .2 para 1524, it was observed that “when the return of the bailed chattel constitutes part of the bailee’s obligation, he must restore not only the chattel itself, but also all increments, profits and earnings immediately derived from it.”

Hence, while the pledgee will not have general rights over the property (and as such, enjoy the accretions, etc.); however, the same may be allowable in terms of mutual contract. In the case of PTC India Financial Services Limited (supra) too, all the rights in the pledged shares had become vested with the pledgee upon becoming the beneficial owner of the shares in the records of the depository as the pledge deed contained clauses to this effect.

In fact, from a lender’s perspective, it would be important that the pledged shares also carry along the voting rights on invocation, such that the voting rights are not exercised by the pledgor to the detriment of the pledgee’s interest.

The Supreme Court in the case of PTC India Financial Services Limited (supra) had held that although flexibility has been provided to parties under the Contract Act to accommodate their unique requirements, a condition prescribed to protect and benefit the public cannot be dispensed with when it lays down a rule of public policy. In Lallan Prasad (supra) too, the SC remarked, “The pawnee’s right of sale is derived from an implied authority from the pawner and such a sale is for the benefit of both the parties.”

Conclusion

To summarise, one may as follows:

- Pledge would be governed by the provisions of the Contract Act. The right of the pawnee for reasonable notice of sale before sale is a fundamental protection and equity of redemption, which cannot be contracted out.

- Pledge does not create general property rights in favour of the pledgee. The pledgee acquires only ‘special property’ and holds the pledged property only as ‘collateral security’ for the sole purpose of repayment of debt.

- As such, the pledgee does not have right of enjoyment of pledged goods, or right to have the accretions in the pledged goods. However, the right to retain the accretion (for example, dividends, bonus shares, etc) may be expressly provided for the contract.

- There is nothing as ‘sale to self’ in pledges. A sale to self, therefore, is void. That, however, does not entitle the pledgor to have the goods back without repayment. The equity of redemption remains in favour of the pledgor subject to repayment of debt.

- “Beneficial ownership” in the context of the Depositories Act should not be confused with beneficial ownership in law. Getting registered as a “beneficial owner” in terms of the Depositories Act does not amount to any transfer of title to the pawnee – it is merely a procedural precondition to sale by the pawnee. .

- The actual sale, that is, sale by pledgee has to be in conformity with the requirement of section 176. The pledgee must tender a ‘reasonable notice’ to the pledgor before causing a sale. A sale which does not conform to such a requirement, is not good in law. The pledgor, subject to repayment of debt before an actual sale happens in conformity with law, shall have the right to redeem the goods. Such right overrides the general rule in favour of a bona fide transferee (except in case of sale of listed shares to an innocent buyer – see detailed discussion above). In case such redemption is not possible, the pledgee can be sued for damages.

- Although there is a requirement of reasonable notice, pledgee cannot be forced to sell the goods. There is no time limit for selling the goods. However, going by the principles of bailment, the authors’ opine that the right must be exercised expeditiously, at the most favourable time in the best interest of both the parties (pledgee and pledgor).

The principles as above, clarified distinctively in the PTC India ruling, may require re-examination of certain current practices (and even continuing agreements ), wherein lenders would avail power of attorney from borrowers to cause a sale of the pledged goods to self. Although such agreements would not be void in totality; however, any sale to self in terms of such clauses would not entitle the pledgee to have better rights than that granted under law – that is – right to cause actual sale, and right to sue for balance. Similarly, such clauses would not take away the rights the pledgor has under law – that is – right to have a reasonable notice of sale, and right to redeem before ‘actual sale’ happens.

However, the question of ‘timeliness’, as in, within what time the pledgee must sell, so far, does not seem to benefit the pledgor. Though, one can say that the question is still not settled in the light of principles of bailment, consumer protection laws and mutual agreement between the parties, and the Courts may still have to fill up the gap.

Besides, the PTC India ruling clearly highlights the need of aligning laws like SEBI’s Takeover Regulations – see para 11.8 of the said ruling. In the view of the authors, the definition of “trading” in the Prohibition of Insider Trading Regulations which seems to cover a pledge as a trade requires reexamination. No beneficial interest, and therefore, no impact of any price movements, passes to the pledgee at all, and therefore, the existing practice of treating the pledge as a trade does not seem to be either desirable or in consonance with the ruling of the Apex Court.

[1] Did we realise that the good old Indian Contract Act, 1872 has turned 150 this year! And still we have courts interpreting and reinforcing its provisions!

[2] Regulation 31 of Takeover Regulations, 2011

[3] Calculated by the author based on the data published at NSE as on 24.06.2022.

[4] RBI’s Report on Sectoral Deployment of Bank Credit for April, 2022.

[5] TOI’s story on NBFC gold loan uptake rose by 20% in Q3 of 2021-22dated 10.03.2022

[6] The article may be read with our other writings on the subject – notably ‘Pledges in the Context of Insider Trading Regulations’, ‘Pledge under SEBI Takeover Regulations, 2011’, ‘Legal aspects of lending against shares’, ‘Various forms of Secured Lending’, ‘Law of pledges in India’, ‘Pledge of Shares: Law, Disclosures and Implications’,

[7] For an elaborate understanding of ‘security interest’ and various forms of security interest, refer Chapter 1 of Part II of Securitisation – Asset Reconstruction and Enforcement of Security Interests, LexisNexis, 2020, by Vinod Kothari. Also, see a presentation titled, ‘Law of Financial Markets and Transactions in India’.

[8] Marquette Law Review: Issue 2, February 1940 defines “conversion” as any distinct act of dominion wrongfully exerted over another’s property in denial of or inconsistent with his rights therein”

[9] Syndicate Bank v. C.H.Muhammed, Sultan and Ors v. Firm of Rampratap Kannyalal, Grison Knitting Works v. Laxmi Commercial Bank Ltd

This is an extremely important ruling, and its implications are immense. We invite users’ feedback on this ruling.