CBDCs in India – A Leap of Faith?

- Megha Mittal, Senior Associate (mittal@vinodkothari.com)

Introduction

Right from RBI’s (in)famous March 2018 Circular (‘Circular’) banning all operations by virtual currency exchanges (VCEs) to the Hon’ble Supreme Court’s verdict upholding the constitutionality of cryptocurrency and its exchanges, the debate over the adaptability of cryptos has led to a demographic split in India.

Ironically enough, despite uncertainty about the legal admissibility of private cryptocurrencies, India has the highest number of crypto-owners in the word at over 10 crore investors[2], which is much higher than the current registered investors with BSE and NSE. Further, as the Ministry of Finance and the RBI continued to maintain their stance on the cons of accepting private cryptocurrencies, the investor volume has only risen despite the high price-volatility witnessed worldwide. The apprehensive stance of FinMin became more evident with the Cryptocurrency and Regulation of Official Digital Currency Bill, 2021 (‘Crypto Regulation Bill’), proposing to ban trading and investments in private crypto-currencies such as Bitcoin.

With all the chatter and anticipated ban on private cryptocurrencies, the focus shifted to the substitute – ‘public’ cryptocurrency, that is, the Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs).

Now, in a landmark step for the Indian Government, the Union Budget 2022-23 has proposed to introduce CBDCs in F.Y. 2022-23. The Budget Speech by the Hon’ble Finance Minister, stated that “Introduction of Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC) will give a big boost to digital economy. Digital currency will also lead to a more efficient and cheaper currency management system. It is, therefore, proposed to introduce Digital Rupee, using blockchain and other technologies, to be issued by the Reserve Bank of India starting 2022-23.[3]”

Through this article, we try to elucidate recent developments in CBDCs, in India and abroad.

CBDCs – A Primer

In recent years, the entire ecosystem of digital and virtual currencies, across economies, has seen significant trends – CBDCs have been a significant component. In 2021, RBI cited the survey of central banks conducted by the Bank for International Settlements, which revealed that around 80% of the 66 responding banks have started projects to explore the use of CBDC, including Canada, USA and Singapore which are currently at different stages – while some have rolled out wholesale models in controlled volumes and jurisdiction, others are conducting simulation programmes to assess impact.

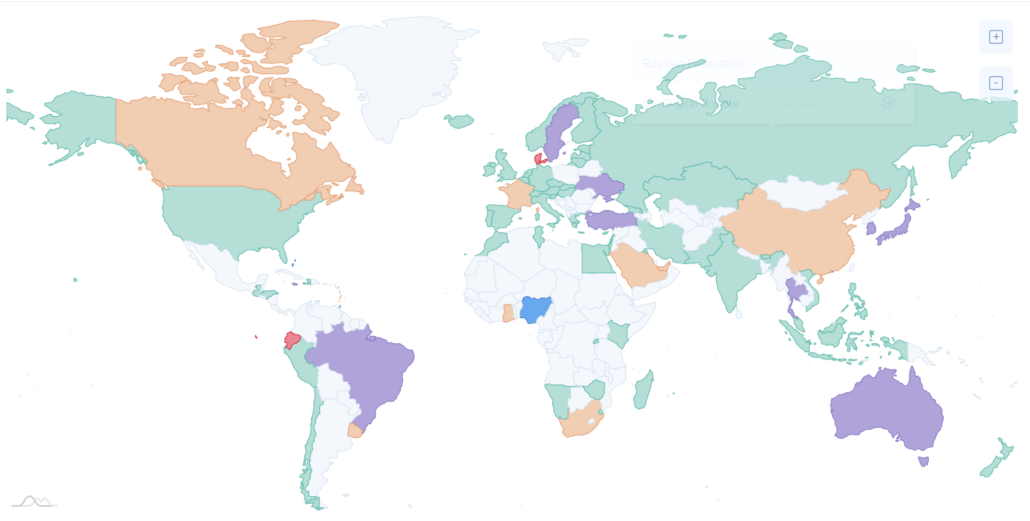

Similarly, as per statistics reported by the CBDC Tracker, as on 31st January, 2022, 61 countries, including India were in the ‘research stage’ of implementing CBDCs, as against 10 countries showing tested a proof of concept. In addition to the same, 12 countries are currently in the pilot stage, while only two, viz. e-Naira in Nigeria and Sand-Dollar in Bahamas have been launched in full-fledged manner. In contrast with these jurisdictions, six countries, including the Scandinavian countries of inland and Denmark have cancelled the prospects of implementing CBDCs[4]. Below is a snapshot showing different the stages of CBDCs’ implementation across different jurisdictions –

Figure 1: Stages of implementation of CBDCs; Source: https://cbdctracker.org/

Now, with CBDCs proposed to be introduced in the coming financial year, it is noteworthy that the Indian Government has taken a leap from the research stage, directly to its implementation. In the discussion below, we discuss the basics and different models of CBDCs along with a brief comparison with the already existing mechanisms in various jurisdictions.

Central Bank Digital Currencies – The Indian Context

In most simple words, CBDC is the digital form of a country’s fiat currency. In one of its publications, RBI defines CBDCs as “the legal tender issued by a central bank in a digital form. It is the same as a fiat currency and is exchangeable one-to-one with the fiat currency. Only its form is different[5]”

In essence, CBDCs are the digital manifestation of the paper currency that the countries have been used to for hundreds of years; and as digitalisation and technology continues to fund its place and relevance in all spheres of life, the shift from the traditional paper and coin currency to digital currency or CBDCs seems to be a natural outcome of the dedicated move towards digitalisation of every aspect of the modern financial system.

Evidently, the fact that CBDCs are issued by the central bank is the first and the foremost distinction that one can draw between private virtual currencies (think Bitcoins[6]) and CBDCs. Before we delve deeper into the different models, and opportunities and limitations associated with CBDCs, it would be beneficial to take note of key similarities and differences between traditional currency; private virtual currencies and CBDCs so as to draw a comparisons between the three at different stages of discussion vis-a-vis CBDCs.

| Basis | Traditional Money (Cash) | Private Virtual Currencies | CBDCs |

| Form | Physical | Virtual | Digital |

| Issuer | Central Bank | Private entities | Central Bank |

| Technology | Distributed Ledger (Blockchain) | Distributed Ledger (Blockchain) | |

| Blockchain type | N.A | Private | Public (Permissionless) |

| Centralisation | Yes | No | Yes |

| Anonymity | Yes | No – users identified to each transaction | |

| Backed by | Domestic Monetary Reserves | No underlying asset/ reserve | Domestic Monetary Reserves |

| Routed through | Commercial banks/ financial institutions | Directly by the Issuer | Directly by the Issuer |

| Accessibility | Only the Issuer and authorised persons | By all participants | By the issuer and authorised persons |

CBDC vs. Digital Money

Theoretically, CBDCs have been in place for several years, the reduced use of cash and an increasing traction towards digital payments, an increasing number of central banks across economies, are preparing to implement CBDCs. However, if CBDCs are to be issued by the Central Bank, how would it be different from the money held in wallets like an ApplePay or a Google Wallet.

A lot of this distinction between already existing digital money and CBDCs would depend on the model through which the latter is sought to be issued and distributed – either directly or through intermediaries. In any case, the key difference would be that CBDCs, once accepted as a separate legal tender, would be final and thus reduce settlement risk in the financial system. For instance, a UPI system, where CBDCs are transacted instead of cash, would minimize/ reduce the need for interbank settlements. The same benefits would become all the more important for international transactions.

In addition to the ease of settlement, another motivation for rolling out CBDCs could be to provide an alternative to the general public from the volatility associated with private cryptocurrencies. Another incentive would be to protect the demand and circulation of physical money.

CBDC vs. Digital Assets

Another crucial distinction would be that of CBDCs and Digital/ Virtual Assets. At the outset, it must be noted that CBDCs are not assets – as discussed above, it is simply currency in digitized form. On the contrary, digital or virtual assets are similar to other assets like plant/ machinery – only existing in a digital, intangible form.

With the Crypto Regulation Bill reflecting a skeptical stance by proposing to ban private cryptocurrencies, there existed a lack of clarity w.r.t. the legality of digital assets as a whole.

However, in a significant development, the Finance Bill, 2022[7] has recognized, and hence validated ‘virtual digital assets’ under the Income Tax Act, 1961. The Finance Bill, 2022 has defined ‘virtual digital assets’ as –

“(a) any information or code or number or token (not being Indian currency or foreign currency), generated through cryptographic means or otherwise, by whatever name called, providing a digital representation of value exchanged with or without consideration, with the promise or representation of having inherent value, or functions as a store of value or a unit of account including its use in any financial transaction or investment, but not limited to investment scheme; and can be transferred, stored or traded electronically;

(b) a non-fungible token or any other token of similar nature, by whatever name called;

(c) any other digital asset, as the Central Government may, by notification in the Official Gazette specify:

Provided that the Central Government may, by notification in the Official Gazette, exclude any digital asset from the definition of virtual digital asset subject to such conditions as may be specified therein.

Explanation – For the purposes of this clause

(a) “non-fungible token” means such digital asset as the Central Government may, by notification in the Official Gazette, specify;

(b) the expressions “currency”, “foreign currency” and “Indian currency” shall have the same meanings as respectively assigned to them in clauses (h), (m) and (q) of section 2 of the Foreign Exchange Management Act, 1999.’.”

(Emphasis supplied)

The above definition implies that –

- CBDCs clearly do not fall under the purview of ‘virtual digital assets’ – it is a currency, which is explicitly excluded from the scope.

- The scope of these ‘virtual digital assets’ shall understandably be under the stringent purview of the Central Government.

Thus, while there may not be a complete washout of private cryptocurrencies, they will understandably be heavily regulated, atleast in the nascent stages.

Taxation –

A significant point of difference is the taxation aspect. It is crucial to understand that while CBDCs are ‘currency’ they are not subject to tax. However, virtual digital currencies, as proposed in the Finance Bill, 2022, have been made subject to high tax incidence.

The key takeaways from the proposed taxation regime vis-à-vis virtual digital currencies are as follows –

- Tax on income on account of transfer of virtual digital currencies shall be at 30%[8]

- The income on such transfer shall only be reduced by the cost of acquiring such asset – deduction of no other nature shall be allowed[9]

- No set off of loss from transfer of the virtual digital shall be allowed from any other profit, whether intra-head or inter-head.[10]

- TDS shall be deductible shall at 1% of the amount of transfer[11]

- The definition of ‘property’ shall include such assets

From the above, one may argue that the tax incidence imposed on transfer of such virtual digital assets are significantly on the higher end, which may act as a demotivator for the use of such assets. Further, given the constant apprehensive stance of the government towards private assets, this may also be taken as a step by the Government to promote the use case of CBDCs vis-à-vis such pseudo-private assets.

Rolling out CBDCs in India

While the approach of implementation has not been explained, relying on RBI’s Paper w.r.t CBDCs,[12] it is understood that the proposed implementation shall be a two-phased approach to examine the use cases which could be implemented with little or no disruption. The two principal models which have been considered by RBI as well as the central banks across several countries are (a) Retail Model and (b) Wholesale Model.

Retail Model –

As the name suggests, the Retail Model proposes a structure wherein individuals can hold and transact in CBDCs. Akin to a payment system, it consists of a three-step transaction-clearing-settlement process. Given its retail nature, the Retail Model witnesses large volumes with low per transaction value.

Depending on the participants in the channel, the Retail Model may be (a) direct; (b) indirect; or (c) hybrid

- Direct Retail Model – As the name suggests, in this model the Central Bank directly takes the role of onboarding, payment and settlement. Evidently, no intermediaries are required and the retail customers have a direct claim on the Central Bank. Given that the Central Banks otherwise do not have a direct interface with retail customers, the Direct Retail Model is generally not preferred by the Central Banks.

- Indirect Retail Model – This model comprises an intermediary layer of financial institutions between the principal issuer viz. the Central Bank and the retail customers.

- Hybrid Model – In this model, while the financial intermediary exists, the retail customers have a direct claim on the Central Bank; the intermediary institutions (generally, banks) keep the CDBCs segregated from their books

Given the proximity of the Retail Model to the cash-based settlements, it promotes financial inclusion alongside presenting a faster shift to a cashless society. Furthermore, retail CBDCs would also help in reducing the costs of cash printing and management. Additionally, since the CBDCs may eventually represent legal tender, they are also expected to play a crucial role in the country’s monetary policy.

Wholesale Model –

In this Model, CBDC transactions take place between the Central Bank and the Financial Institutions – they are more suitable for the reserves to be kept by these intermediaries as per norms laid down by the Central Bank.

According to the Bank of International Settlements, wholesale CBDCs can present potential benefits for payment and settlement systems. The performance of wholesale CBDCs in different pilot experiments by several central banks also presents their potential advantages. The CADcoin in Canada, Project Ubin in Singapore, as well as Project Stella in the Japan-Euro Area, are some of the leading examples of wholesale CBDCs.

Setting up a Legal Ecosystem for CBDCs

While the motivations and benefits of CBDCs could range from a rapid payments and settlement system to financial inclusion and better monetary policies, it also brings to the table several concerns and challenges that need to be addressed before rolling out. Below we enlist some key challenges that are anticipated for actual implementation, especially in the Indian context –

- KYC Requirements and Anonymity – A Trade off

Given the existing number of active investors in private cryptocurrencies, it is expected that CBDCs, if rolled out, shall also attract significant traction. This increased number of users in the novel field will only lead to a heightened risk of privacy breach of the users. This increase in the number of users would simultaneously also require comprehensive safeguards from an anti-money laundering perspective.

Additionally, it is important to note that the momentum that CBDCs have gained off-late is essentially due to the drawbacks prevalent in private cryptocurrencies or the slightly modified stablecoins[13], the first and foremost being complete anonymity of transactions. Thus, tracing of transactions and identification of parties would be crucial to combat and mitigate risks such as money laundering and terror financing.

That being said, while KYC norms would be indispensable from the CBDC ecosystem, the degree of the anonymity provided in the transactions would be crucial to determine their success (or failure) especially in the Retail Model. Given that cash transactions offer significant anonymity to the parties, it is very often found that users prefer cash over digital payments for everyday transactions. Hence, the trade-off between KYC requirements and degree of anonymity must be achieved so as to ensure feasibility.

- Setting up a Regulatory Infrastructure

Basis the models discussed above, it was clear that implementation of either of the models would have required setting up of a holistic regulatory infrastructure inter-alia clearly defined roles and responsibilities of the different stakeholders, amendments in extant laws like the RBI Act, 1934, Payments and Settlement Act, 2007; constituting a dedicated regulatory body for dealing with CBDCs. Additionally, prudential and reporting aspects shall also warrant due care and consideration.

In this regard, the Finance Bill, 2022 has proposed requisite amendments[14] in the Reserve Bank of India Act, 1934 inter-alia inclusion of ‘digital currencies’ in the definition of ‘bank note[15]’

Other than providing for an ecosystem conducive for CBDCs, another aspect that would require attention is identification and empowerment to intermediaries, so as to ensure a hassle free flow of transactions, it is crucial to identify which institutions and/ or bodies shall act as intermediaries and thereafter, to empower them to act as such, under their respective statutes.

Conclusion

With CBDCs now a global phenomenon, the RBI has taken a significant steps to break-in the crypto ecosystem. However, to sufficiently gauge its viability and feasibility in India, a great deal will depend on the mode and manner of implementation. In the Indian perspective, given that digital payments through Paytm or Google Pay and other similar wallets have gained tremendous popularity, it is expected that a similar reaction may be received for CBDCs.

[1] This article has also been contributed by Mr Sameer Gehlot

[2] As per report released by the broker discovery and comparison platform BrokerChooser

[3] https://www.indiabudget.gov.in/doc/Budget_Speech.pdf – Para 111

[4] https://cbdctracker.org/ [last visited on 1st February, 2022]

[5]https://rbidocs.rbi.org.in/rdocs/Speeches/PDFs/CBDC22072021414F2690E7764E13BFD41DF6E50AE0AE.PDF – Para 7

[6] Read more about private virtual currencies like stablecoins and bitcoins – https://vinodkothari.com/2020/07/recent-trends-crypto-industry-india-abroad/ and https://vinodkothari.com/2020/04/the-rise-of-stablecoins-amidst-instability-gsc-covid/

[7] https://www.indiabudget.gov.in/doc/Finance_Bill.pdf

[8] Proposed section 115BBH(1)(a)

[9] Proposed section 115BBH(1)(b) and 115BBH(2)(a)

[10] Proposed section 115BBH(2)(b)

[11] Proposed section 194S (1)

[12] Refer to Note 4

[13] https://vinodkothari.com/2020/04/the-rise-of-stablecoins-amidst-instability-gsc-covid/

[14] In section 2 and 22 of the Reserve Bank of India Act, 1934

[15] Section 2(a)(aiv) of the Reserve Bank of India Act, 1934

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!