By Nikita Snehil, (corplaw@vinodkothari.com)

Striking off of the names of companies for having remained inoperative has been a concept which has always been there, both under the 1956 Act, and under the 2013 Act. Striking-off of defunct companies is a provision in law for chopping the dead wood – if the company has lost its substratum, and there is nothing in the company, then the long process of winding up is not relevant for the company, and the RoC can strike off the name of the company as if the company never existed. Striking-off of companies is an option that exists both with the company, and with the RoC.

However, the recent massive clean-up operation, whereby RoCs started issuing public notices[1] in April, 2017 to strike off the name of the companies from the register of companies and to dissolve them unless a cause is shown to the contrary, within thirty days from the date of the notice, has come to centre of focus. Thereafter, on September 5, 2017 the government confirmed that names of over 2.09 lakh companies have been struck off from the Register of Companies for failing to comply with regulatory requirements.

There are several words which are doing rounds currently – defunct companies, shell companies, benami companies, and so on. They all mean completely different things. Defunct company is what the Companies Act talks about – a company which is left with no substance; it is either inoperative, or has no assets or liabilities. The word “shell company”, commonly used in tax parlance, refers to such companies which are merely a shell, that is, hiding the identity of the real owners. Obviously, the current environment of the drive against black money suggests that the word has been used to refer to companies which might have been used for money-laundering. The word benami company might have similar connotations.

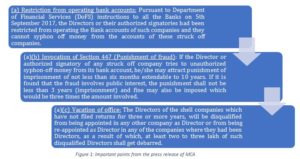

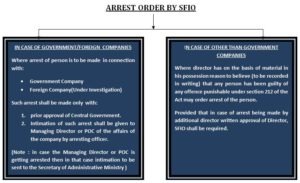

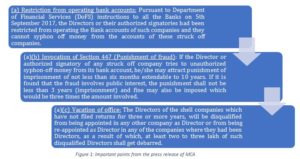

However, the Companies Act term “defunct” companies never really smelled about money laundering or a device to shield the identity of real owners. Therefore, over the years, the concept has been innocuous. In the current environment, however, the various expressions above have all been mixed up, as if to conclude that defunct companies were being used for money-laundering. If the company is really defunct, and there is no substance into it, it seems paradoxical to relate it to money laundering operations. The fact that there is no real asset or no real liability should mean that there is nothing in the company, including any evidence of untaxed wealth. However, the confusion between defunct companies and black money is quite evident in the MCA press release[2] issued on September 6, 2017 said that the action of the MCA “would not only help in checking the menace of black money” but would help the ease of doing business in India. The Press Release also sounded like a shock to the directors of such struck-off companies, as it said 3 important points:

This article endeavours to understand the provisions of the law about striking off of names of companies and the impact thereof on directors’ disqualifications.

Enabling provision of the law

As per Section 248 of the Companies Act, 2013 (‘Act’) which deals with the power of Registrar to remove name of company from register of companies:

“(1) Where the Registrar has reasonable cause to believe that—

(a) a company has failed to commence its business within one year of its incorporation;

(b) [omitted]

(c) a company is not carrying on any business or operation for a period of two immediately preceding financial years and has not made any application within such period for obtaining the status of a dormant company under section 455,

he shall send a notice to the company and all the directors of the company, of his intention to remove the name of the company from the register of companies and requesting them to send their representations along with copies of the relevant documents, if any, within a period of thirty days from the date of the notice.”

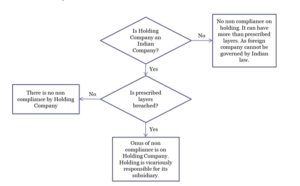

Therefore, though the public notice issued by the RoC stated the reference of Section 248 of the Act, it is pertinent to note that the said Section empowers the RoC to strike the names of the Companies only in two cases. But almost all the shell companies does not seem to have triggered any of the above two conditions.

Section 248 Vs Section 455 of the Act

Another section which empowers RoC to remove the name of a company from the register of members is Section 455 of the Act. As per the provisions of Section 455 of the Act, which deals with the provisions of dormant company:

“(4) In case of a company which has not filed financial statements or annual returns for two financial years consecutively, the Registrar shall issue a notice to that company and enter the name of such company in the register maintained for dormant companies.

(5) A dormant company shall have such minimum number of directors, file such documents and pay such annual fee as may be prescribed to the Registrar to retain its dormant status in the register and may become an active company on an application

made in this behalf accompanied by such documents and fee as may be prescribed.

(6) The Registrar shall strike off the name of a dormant company from the register of dormant companies, which has failed to comply with the requirements of this section.”

The section states the following procedure to be adopted by the the dormant company and the RoC:

(a) RoC may remove the name of an inactive company from the register of members and put the same in the register of dormant companies.

(b) The dormant company shall then comply with the requirements and retain its dormant status or make an application to become an active company.

(c) Thereafter, if the dormant company fails to comply with the requirements of the section, then the RoC can finally remove the name of such company from the register of dormant company as well.

However, in the current situation, the above mentioned procedure is not followed by the RoCs and names of the companies are directly struck off from the register of members.

Hence, there does not seems to be an enabling section under which the RoC has struck off the names of the companies.

Vacation of office of Directors

As per the Press release issued by MCA, the next move of MCA will be to compel the Directors of such shell companies which have not filed returns for three or more years to vacate the office.

Provisions of law:

Section 164 (2) of the Act, which deals with the disqualifications of appointment of directors, provides the following:

“No person who is or has been a director of a company which—

(a) has not filed financial statements or annual returns for any continuous period of three financial years; or

(b) has failed to repay the deposits accepted by it or pay interest thereon or to redeem any debentures on the due date or pay interest due thereon or pay any dividend declared and such failure to pay or redeem continues for one year or more,

shall be eligible to be re-appointed as a director of that company or appointed in other company for a period of five years from the date on which the said company fails to do so.”

Further, Section 167(1)(a) of the Act directs that the office of a director shall become vacant in case he incurs any of the disqualifications specified in section 164 of the Act.

Therefore, reading both the sections, it can be concluded that, the directors of such companies will:

1. have to vacate their office, due to the disqualification incurred;

2. not be able to be re-appointed as a director of that company;

3. not be eligible to be appointed in any other companies as well.

The second and third effect will last upto a period of five years from the date on which the said company fails comply with the provisions of section 164 (2) of the Act.

Having said so, there arises a further question:

‘Does disqualification to section 164(2)(b) of Act will also apply to directors newly appointed in the company?’

It is important to note the starting lines of section 164(2)(b), which read as follows:

“No person who is or has been a director of a company which xxX”

Thus, to attract disqualification under section 164(2)(b), it is important that the individual has to be on the board of the company when the default actually happened.

Therefore, even new directors of such company will attract the disqualification, inspite of the fact that they were not at all involved in such non-compliance. Basically, the intent of law might be to deter companies from defaulting, which would demotivate any new director to join the company.

Applicability of the law – prospective or retrospective?

Sections 164 and 167 came into force on April 1, 2014. However, the disqualifications under Section 164 (2) cannot become applicable as on April 1, 2014 for any annual filings not done in any of the previous financial years. The provisions were initially inapplicable to private companies. Section 164 (2) curtails the right of directors of such companies to continue as directors, casts a new burden, imposes a new liability on such directors for having defaulted in filing financial statements for any 3 continuous financial years.

It was discussed in the Supreme Court Judgment in case

of Maharaja Chintamani Saran Nath … vs State Of Bihar And Ors on 7 October, 1999[3] that the true principle is that Lex prospicit non respicit (law looks forward not back). As Willes, J. said, retrospective legislation is `contrary to the general principle that legislation by which the conduct of mankind is to be regulated ought, when introduced for the first time, to deal with future acts, and ought not to change the character of past transactions carried on upon the faith of the then existing law.

However, in the recent case law of “Vikram Ahuja Vs. Greenstone Investments Pvt. Ltd. and ors., before the NCLT, Mumbai Bench, decided on November 11, 2016”[4], one of the point for discussion and decision before the Hon’ble bench was:

“whether the disqualification set forth in Section 164(2)(a) read with 167(1) (a) of the Act has retrospective effect or not?”.

The Hon’ble Tribunal, after considering various case laws considered that “this provision has to be read as applicable to the situations where non-filing has started, at the most in the past and continuing while this enactment has come to into existence and also to future non-filing”. Also, it has been provided that, the statute providing posterior disqualification on past conduct does not become a retrospective one because a part of a requisition for its action is drawn from a time antecedent to its passing.

Therefore, the applicability of the Section, whether retrospective or prospective is still debatable.

Legal position of the company after strike-off

By virtue of a legal process, a company is born as a separate legal entity, so is its death process. In case of dissolution of a company pursuant to the company’s name being removed from the Register by the ROC in terms of Section 248 of the Act, the corporate status of an entity ceases to subsist, its functionality stops and for all practical purposes corporate activities come to an end.

Liability of directors

The pertinent question that arises here is that whether the liability of directors and other officers of the company struck off from the records will continue and whether it could be enforced. The answer to this is yes.

The relevant clause of Section 248 of the Act provides the followings:

“(7) The liability, if any, of every director, manager or other officer who was exercising any power of management, and of every member of the company dissolved under sun-section (5), shall continue and may be enforced as if the company had not been dissolved.”

Accordingly, it can be drawn that notwithstanding the company’s dissolution, the liabilities of its directors and officers who exercised powers along with its members continue, remain unaltered and enforceable. However, the dissolution does not makes any enhancement to the enforcement of the liabilities affecting the personal capacity of the abovementioned persons.

A view can be taken that the dissolution under section 248 is not a state complete extinction. Instead it is a state of suspension for a period of twenty years from the date of dissolution, as upon the revival of the company, all its rights and liabilities are restituted with retrospective effect from the date of strike-off.

Assets of the company

Another concern for a company whose name has been struck-off by the ROC is that there may be properties and rights vested in or held on trust for the company, cash balances of the company and other current or non-current assets of the company while it was functional. The fate of such assets is a question to be addressed.

Section 352(2) and 352(7) of the Act deals with the unclaimed or undistributed estate of a company, but these sections becomes applicable where there is a liquidator involved in winding up of a company. In case a company is dissolved in pursuance of Section 248, there is no liquidator appointed. Hence, the operative part of Section 352 is not applicable in the dissolution of a company under Section 248.

A reference can be drawn from the Companies Act of England, which has a provision stating that the property of dissolved company shall be bona vacantia. The Escheat over which no one has a claim is known as bona vacantia. The term can be expressed as ‘abandoned property’ too. In bona vacantia there is no owner of the property and the State merely takes possession of the property, which is an abandoned one. In India there is no such corresponding provision in the Act. However, as per the laws in India, the property of an estate dying without leaving lawful heirs passes to the government by escheat or as bona vacantia. Similarly, it can be inferred that the property of a dissolved company shall also pass to the government by escheat or as bona vacantia, including any subsisting interest of the company on the date of dissolution.

Though, it can be established that the doctrine of bona vacantia will be applicable for a company dissolved under section 248, however, whether the same shall come into operation immediately or after a lapse of the prescribed time period of twenty years is a debatable matter.

Effect of company notified as dissolved

As per Section 250 of the Act, where a company stands dissolved under section 248, it shall on and from the date mentioned in the notice issued by RoC in the Official Gazette, shall cease to operate as a company and the Certificate of Incorporation issued to it shall be deemed to have been cancelled from such date except for the purpose of realising the amount due to the company and for the payment or discharge of the liabilities or obligations of the company.

Recent judgements:

NCLT, at its hearing of Principal Bench at New Delhi, on March 14, 2017, in the case of Poly Auto System Pvt. Ltd. Vs. RoC Delhi[5], held that the Registrar of Companies has to comply with the comprehensive procedural obligations before passing the final order of striking off the name of the company from the register of members. The casual approach of the RoC which would lead to abrupt conclusion will not be a legal act. And the Tribunal ordered for restoration of the name of the Company in the register of members.

Similarly, the present act of the government of striking off the names of more than 2 two lakh companies, seems not to consider the post effect of such dissolution.

So, it will be interesting to see how the assets and liabilities of the companies will be managed – will there be appointment of any liquidator? How will the liabilities of the creditors will be discharged? Will the balances of the cash rest with the government? These are the few questions which will have to be addressed by the government in the due course.

Remedial Action

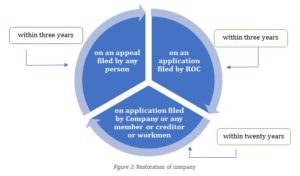

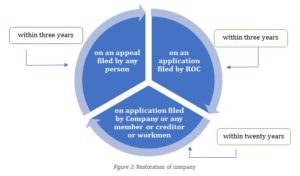

Section 252 of the Act empowers the Tribunal, to pass an order for the restoration of company which has been struck off by the ROC, in the following manner:

(a) Appeal filed by any person:

Any person aggrieved by the order of the RoC may file an appeal before the Tribunal within 3 years of the order passed by RoC and if the Tribunal is of the opinion that the removal of name of company is not justified in view of the absence of any of the grounds on which the order was passed by the ROC, it may pass an order for restoration of the name of the company in the register of companies after giving a reasonable opportunity of making representations and of being heard to the ROC, the company and all the persons concerned. The genuine companies, which have been struck off, will move to file an appeal to the NCLT in this case.

(b) Application filed by ROC:

The ROC may, within a period of three years from the date of passing of the order dissolving the company under section 248, file an application before the Tribunal seeking restoration of name of such company if it is satisfied that the name of the company has been struck off from the register of companies either inadvertently or on the basis of incorrect information furnished by the company or its directors. Genuine companies may make representations to prove their innocence or bonafide reason of such non-filings, pursuant to which RoC may on valid reasons but within a period of three years, restore the name of such companies.

(c) Application filed by company or any member or creditor or workmen:

The Tribunal, on an application made by the company, member, creditor or workman before the expiry of 20 years from the publication in the Official Gazette of the notice of dissolution of the company, if satisfied that:

1) the company was, at the time of its name being struck off, carrying on business or in operation; or

2) b) otherwise it is just that the name of the company be restored to the register of companies,

may order the name of the company to be restored to the register of companies. Further, the Tribunal may also pass an order and give such other directions and make such provisions as deemed just for placing the company and all other persons in the same position as nearly as may be as if the name of the company had not been struck off from the register of companies.

Therefore, in the present situation, it will be best for the genuine companies to make representations/ applications to the RoCs proving that the companies are not involved in any fraudulent activities or involved in syphoning of funds through illicit activities. The representations/ applications may convince the RoC to restore the names of the genuine companies.

[1] http://www.mca.gov.in/MinistryV2/roc.html

[2] http://pib.nic.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=170579

[3] https://indiankanoon.org/doc/1293868/

[4] http://nclt.gov.in/Publication/Mumbai_Bench/2016/397_398/Greenstone%20Investments%20Pvt.%20Ltd.%2022.11.2016_.pdf

[5] http://nclt.gov.in/interim_orders/principal/14.03.2017/Poly%20Auto%20Systems%20Pvt.%20Ltd..pdf