Sustainable finance and GSS+ bonds: State of the Market and Developments

– Vinod Kothari and Payal Agarwal | corplaw@vinodkothari.com

The topic of sustainable finance has become as critical as sustainable development, since finance is the prerequisite for sustainable development. “Finance can play a leading role in allocating investment to sustainable corporates and projects and thus accelerate the transition to a low carbon and more circular economy. Moreover, investors can exert influence on the corporates in which they invest. In this way, long-term investors can steer corporates towards sustainable business practices.”[1] Hence, there is momentum towards organising funds and resources to transition from low energy efficiency to high energy efficiency, or renewable energy devices.

The expression “sustainable finance” is broader, as it encompasses the use of ESG considerations in financing decisions.[2] However, sustainability bonds are capital market instruments issued with a stated end-use. The term GSS+ bonds, which has recently been much in vogue, has G, S, S and then augmented by the + sign. The components of “GSS+” are as follows:

G : Green

S: Social

S: Sustainability

+ : Other labeled bonds, particularly, transition bonds, and depending on the usage, may also include sustainability-linked bonds.

The other labeled bonds may also include blue bonds, gender bonds, climate bonds, yellow bonds etc., although the same may already be covered under one of the components of the GSS bonds. For instance, blue bonds are taken as a part of green bonds, and gender bonds are taken as a part of social bonds.

GSS+ bonds are also called “thematic” or “labeled” bonds, with the use of their proceeds linked with the respective theme represented by such bonds. These expressions may be somewhat overlapping[3].

Contents

Meaning and types of GSS+ bonds

Major issuers of GSS+ bonds by issuer type

Sovereign issues vs private issuers

Difficulties in sovereign issuance of thematic bonds

Legal framework on GSS+ bonds in India

Motivations for issuance of thematic bonds

Investor’s perspective on thematic bonds

Meaning and types of GSS+ bonds

As discussed above, the term GSS+ bonds expand as Green, Social, Sustainability and other labeled bonds. These bonds are primarily debt instruments that are linked with their end use dedicated to environment, climate, social objectives, sustainability, etc.

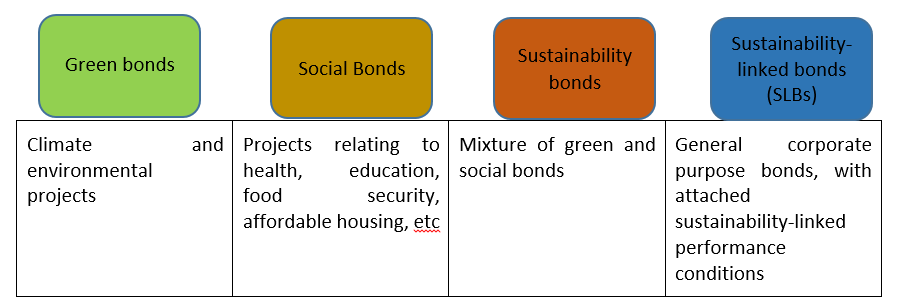

The voluntary guidelines framed by International Capital Market Association (ICMA), which seems to have become the globally accepted norm, recognise 4 types of bonds that are connected with sustainable financing (refer figure 1) –

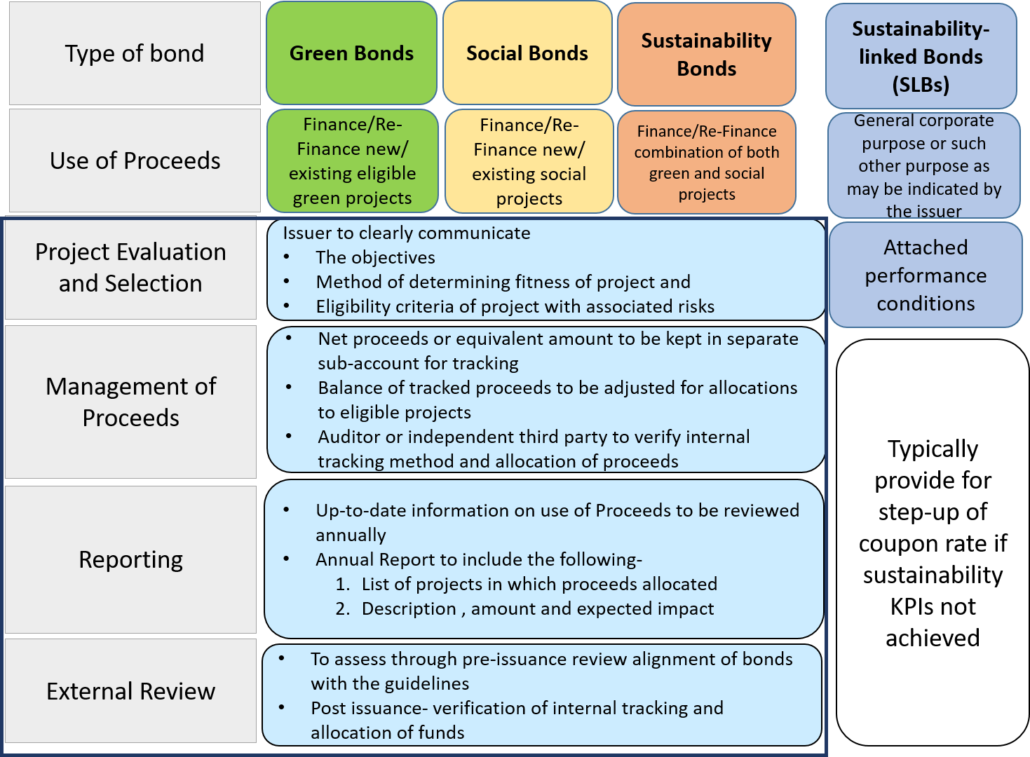

Separate guidelines[4] have been issued by ICMA in respect of each of these bonds. A snapshot showing the comparative between these 4 types of bonds is as follows (refer figure 2) –

Green bonds

The largest component of the GSS+ bonds universe is green bonds. As per the Green Bond Principles[5] (GBP) issued by ICMA, green bonds refer to “any type of bond instrument where the proceeds or an equivalent amount will be exclusively applied to finance or re-finance, in part or in full, new and/or existing eligible Green Projects and which are aligned with the four core components of the GBP.

The four core components of the GBPs are:

- Use of proceeds:

The use of the funds should be exclusively for identified “green projects”. In case of multiple projects, each of the projects should be green, and the offer documents should highlight clearly the environmental benefits assessed and quantified by the issuer. “Green projects” include broad categories such as climate change mitigation, climate change adaptation, natural resource conservation, biodiversity conservation, and pollution prevention and control.

- Process for Project Evaluation and Selection:

The issuers are required to communicate the environmental sustainability objectives of the project, and the process by which the eligibility of the project has been determined by the issuer, as well as complementary processes in place to identify and manage the social and environmental risks associated with such projects. In addition to the same, the issuers are also encouraged to disclose certifications or standards referenced in the project selection, and have proper processes to identify the mitigants to known material risks in relation to the project.

- Management of Proceeds:

Since green bonds are “use-of-proceeds” bonds, the monitoring of the utilisation of the proceeds becomes significant. The net proceeds or an equivalent amount thereto, should be credited to a sub-account or otherwise, allocated in such a manner so as to facilitate tracking of the same. The issuers are also required to disclose to the investors, the intended types of temporary parking of the unutilised proceeds. While the issuer is required to maintain an internal tracking of the utilisation of the proceeds, the engagement of an external auditor is recommended to verify the allocation of funds and the internal tracking process.

- Reporting :

Transparency is of particular value in communicating the expected and/ or achieved impact of the green projects and to this end, the issuers are required to make readily available, up-to-date information on the use of proceeds on an annual basis and on a timely basis in case of material developments. Impact reporting may be of significance and a summary, reflecting the main characteristics of the project may help the market participants in taking an informed decision. The ICMA also provides sample information templates to this effect.

While the GBP provides an indicative (not exhaustive) list of eligible Green Projects, the basic underlying principle towards identification of eligibility of a project is the existence of clear environmental benefits. An indicative list of the categories of the eligible Green Projects in terms of the GBP are as below (also refer figure 3) –

- renewable energy

- energy efficiency

- pollution prevention and control

- environmentally sustainable management of living natural resources and land use

- terrestrial and aquatic biodiversity

- clean transportation

- sustainable water and wastewater management

- climate change adaptation

- circular economy adapted products, production technologies and processes and/or certified eco-efficient products

- green buildings

The label “Green bonds” seems to have been first used by the World Bank in 2008[6]. This was soon followed by IFC’s green bonds in 2010. IFC remains one of the largest issuers of green bonds with a cumulative volume of $10.5 billions worth of green bonds issuance as of 30th June, 2022. The IFC has published its own Green Bonds Framework and a step-by-step guide to issuing a green bond, the Green Bond Handbook, in alignment with the voluntary GBP laid down by ICMA.

Similar standards have also been issued by the Climate Bonds Standard Board and the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN). All these standards are voluntary in nature and aligned with the ICMA Guidelines with some modifications of their own.

Types of green bonds

Green bonds can further be classified into 4 broad types –

- Standard Green Use of Proceeds Bond – These are unsecured debt obligations with full recourse to the issuer only in the event of default in repayment to the investors.

- Green Revenue Bond – These are debt obligations with no recourse to the issuer in which the credit exposure in the bond is to the pledged cash flows of the revenue streams, fees, taxes etc., and whose use of proceeds go to related or unrelated Green Project(s).

- Green Project Bond – These are project bonds for a single or multiple Green Project(s) for which the investor has direct exposure to the risk of the project(s) with or without potential recourse to the issuer.

- Secured Green Bond – These are secured bonds, the net proceeds of which can be used to finance or re-finance the specific Green Project securing the bond (“Secured Green Collateral Bond”) or other Green Projects of the issuer, sponsor or originator, which may or may not be forming part of the security for the bond (“Secured Green Standard Bond”). These are generally secured structures in the form of covered bonds, securitisations, asset-backed commercial paper, secured notes etc where the cash flows of assets are available as a source of repayment or assets serve as security for the bonds in priority to other claims.

Social bonds

Similar to green bonds, social bonds are such bond instruments where the proceeds or an equivalent amount are utilised towards financing or re-financing of eligible social projects. These bonds are also required to align with the four core components of the Social Bond Principles (SBP), and are similar to that of GBP.

Social projects would generally mean any project with clear social benefits. The SBP provides an indicative list of eligible Social Projects, such as (also refer figure 4)–

- Affordable basic infrastructure

- Access to essential services

- Affordable housing

- Employment generation, and programs designed to prevent and/or alleviate unemployment stemming from socioeconomic crises, including through the potential effect of SME financing and microfinance

- Food security and sustainable food systems

- Socioeconomic advancement and empowerment

The target population or beneficiaries of eligible Social Projects include, but are not limited to, people living below the poverty line, excluded and/or marginalised populations and/or communities, people with disabilities, migrants and/or displaced persons, undereducated, underserved, unemployed, women and/or sexual and gender minorities, aging populations and vulnerable youth and other vulnerable groups, including as a result of natural disasters.

These bonds are said to have emerged in 2013[7] with the launch of the “Banking on Women” bond issue programme by the IFC. As per the Sustainable Debt Market Summary H1 2022 published by Climate Bonds Initiative, the volume of social bonds issuance ranked third in the overall sustainable debt markets in the world.

ICMA recognises four broad types of social bonds, similar to that of the green bonds, that is to say, Standard Use of Proceeds Social Bonds, Social Revenue Bonds, Social Project Bond and Secured Social Bonds.

Sustainability bonds

Sustainability bonds form the second largest component of the GSS+ label. The end-use of proceeds in this case is not on projects that are either “green” or “social”, but a combination of both “green and social” projects. It includes those projects that intentionally mix both green and social benefits. Sustainability bonds provide flexibility over the green and social bonds, and are therefore, preferred over the social bonds at least. The volume of sustainability bonds issuance accounted for 21% of the total sustainable debt market in H1 2022[8].

Sustainability-linked bonds

As per the ICMA’s Sustainability-linked Bond Principles, “sustainability-linked bonds (“SLBs”) are any type of bond instrument for which the financial and/or structural characteristics can vary depending on whether the issuer achieves predefined Sustainability/ ESG objectives.”

The SLBs have distinguishing features, as compared to the other sustainable finance bonds, the latter being in the nature of “use of proceeds” bonds. In other words, the proceeds of an SLB-linked bond may be used for any corporate usage, as in case of a usual corporate bond. The only speciality is that the bond issuer sets a clear performance target, and agrees to suffer a penalty, mostly in form of higher coupons, if the target is not met.

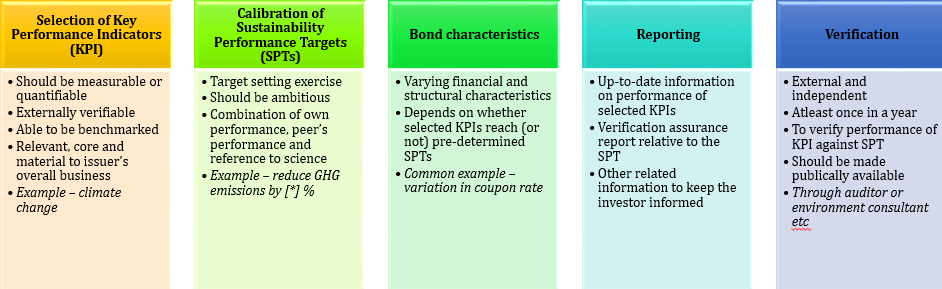

SLBs rest on five key pillars, as follows (refer figure 5) –

The SLBs require companies to frame key performance indicators (KPIs) and Sustainability Performance Targets (SPTs). To give an example, a company may frame its sustainability performance target to reduce its greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 20% compared to that of a base year. In this case, the key performance indicators can be reduction of CO2 emissions, reduction of carbon footprint etc.

The coupon payable to investors is linked with KPIs. If the KPIs are not met, the coupon is typically stepped up[9].

The use of proceeds of SLBs are not guided, and can be issued for “general corporate purposes” too.

Transition bonds

Transition bonds are a subset of sustainable debt finance instruments whereby the issuer is raising funds in debt markets for climate and/or just transition-related purposes[10].

They can take the following forms:

- Use of Proceeds instruments, defined as those aligned to the Green and Social Bond Principles or Sustainability Bond Guidelines; or

- General Corporate Purpose instruments aligned to the Sustainability-Linked Bond Principles.

These bonds are generally issued to fund a company’s transition towards reduced environmental impact or lower carbon emissions. They may not qualify as “green bonds”, since they are often issued in fields that would not normally qualify for green bonds, such as large carbon-emitting industries like oil and gas, iron and steel, chemicals, aviation and shipping[11].

Building a lower carbon economy and meeting the net zero target by 2050 as laid down in the Paris Agreement, a major transformation is required by a number of large sectors, particularly, energy, transport and other industries[12]. The transition bonds or transition financing is aimed at raising funds towards such transformation, or transition from a higher carbon economy to a lower carbon economy.

ICMA has also issued guidance for issuers, Climate Transition Finance Handbook, towards issuance of financing instruments with climate ‘transition’ label. As discussed, the form of the instrument may either be a “use-of-proceeds” bond or a sustainability-linked bond. The key elements of the recommendations of ICMA towards transition bond issuance are –

- Issuer’s climate transition strategy and governance

The issuer shall clearly communicate its corporate strategy of how the issuer intends to adapt its business model to make a positive contribution to the transition to a low carbon economy. Therefore, establishment of a corporate strategy to this effect is a pre-requisite for transition labeled bonds. Such strategy may be disclosed through adoption of recognised reporting frameworks such as TCFD, sustainability reporting etc. Further, the provision of an independent technical review of the issuer’s strategy may assist investors in developing a view regarding the credibility of the issuer’s strategy insofar as it addresses climate change risk issues.

- Business model environmental materiality

Climate transition financing should relate to the ‘core’ business activities of the issuer that are environmentally material. The same should be applied towards a future success of the business model, as opposed to an incidental object. As regards the determination of materiality is concerned, existing market guidance may be applied.

- Climate transition strategy to be ‘science-based’ including targets and pathways

The climate transition strategy of the issuer should be ‘science-based’. The targets should be quantitatively measurable, referenced with appropriate benchmarks and science-based trajectories, with public disclosures including that of the interim milestones, and backed by independent assurance or verification.

- Implementation transparency

Transparency should be ensured, to the extent possible, on the allocation and utilisation of the transition finance raised. This may include disclosure of capex and opex plans, R&D expenditure, expenses that are not considered “business as usual” etc.

The Climate Bonds Initiative has also developed the Climate Bonds Standard and provides certification to the projects meeting such standards. The existing version of the Standard was released in December, 2019 and a draft version of the Standard has been released for public consultation during Sep, 2022.

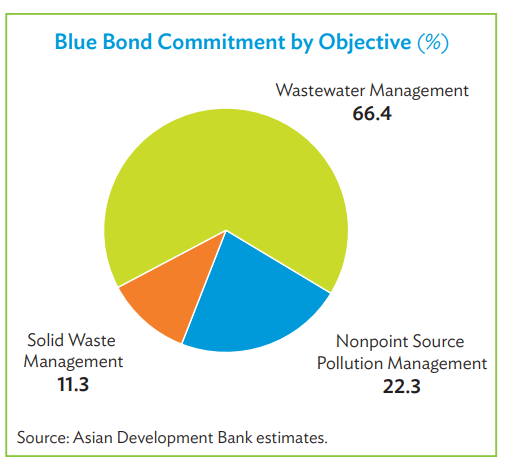

Blue bonds

Blue bond is defined by the World Bank as “a debt instrument issued by governments, development banks or others to raise capital from impact investors to finance marine and ocean-based projects that have positive environmental, economic and climate benefits.” The Asian Development Bank (ADB) defines blue bond as “a relatively new form of a sustainability bond, which is a debt instrument that is issued to support investments in healthy oceans and blue economies.” The UN Environment Programme – Finance Initiative further lays down the Sustainable Blue Economy Finance Principles. In addition to the same, the UNGC has also published a practical guidance to issue a blue bond.

To this effect, the ADB has also issued an updated Green and Blue Bond Framework. The Framework is consistent with the Green Bond Principles of ICMA and the Blue Economy Principles of UN. The International Finance Corporation has also issued the Guidelines for Blue Finance in January, 2022.

The eligible projects that can be funded by way of blue bonds are –

- Marine and Coastal Ecosystem Management and Restoration

- Marine Pollution Control

- Sustainable Coastal and Marine Development

- Water supply

- Water sanitation

- Ocean-friendly and water-friendly products

- Ocean-friendly chemicals and plastic-related sectors

- Offshore renewable energy facilities

- Sustainable shipping and port logistics sectors

- Fisheries, aquaculture, and seafood value chain

It is to be noted that due to the interconnection between a green bond and a blue bond, situations may arise where an instrument is eligible to be classified as both. However, the ADB Framework has clarified that no instrument can be allocated to both green and blue bonds portfolio at one time, and therefore, in such cases, on the basis of the primary project objectives, target results and market demands, the ADB will determine as to whether the project falls into green bond portfolio or blue bond portfolio.

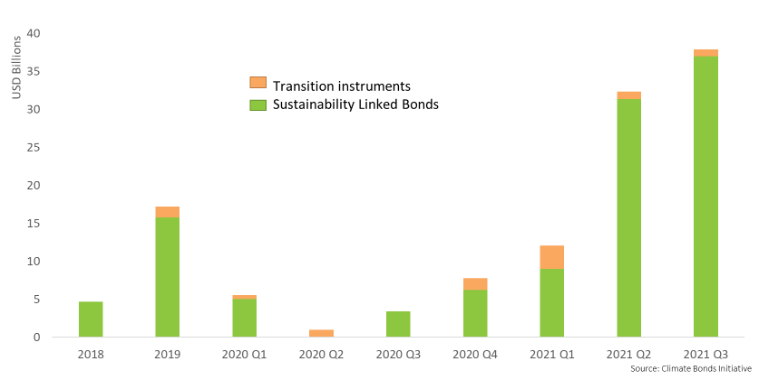

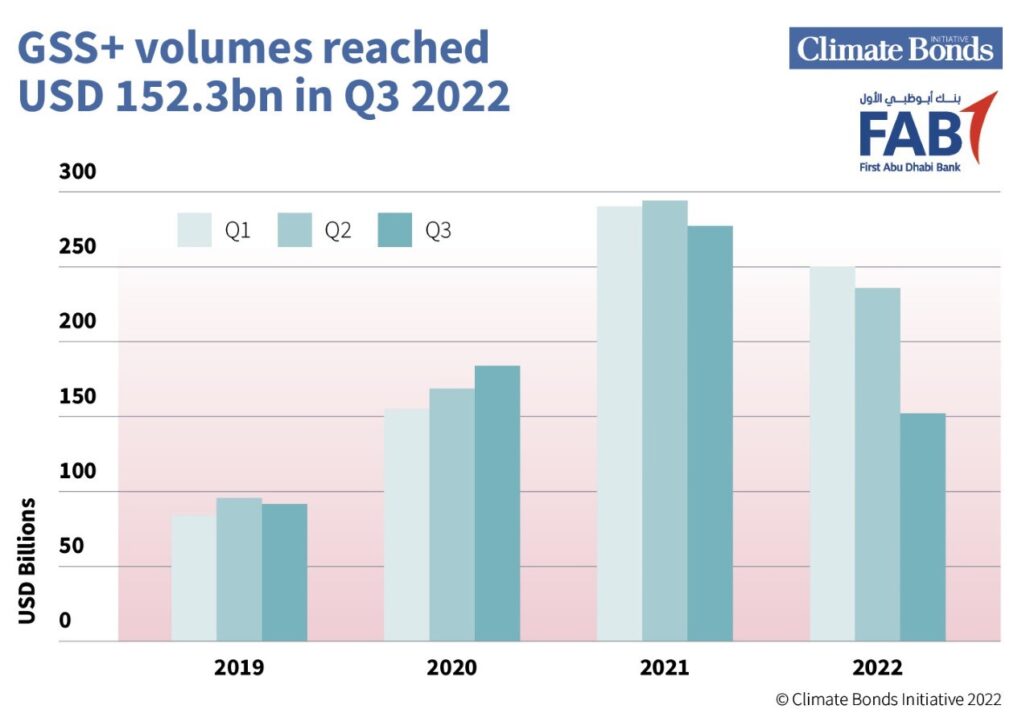

Growth of GSS+ bonds

The volumes of GSS+ bonds are monitored by several agencies; relying on the data by Climate Bonds Initiative, the issuance in 2022 is expected to be lower than that in 2021. The reasons are the generally prevalent inflationary conditions in several economies, and the geopolitical tensions.

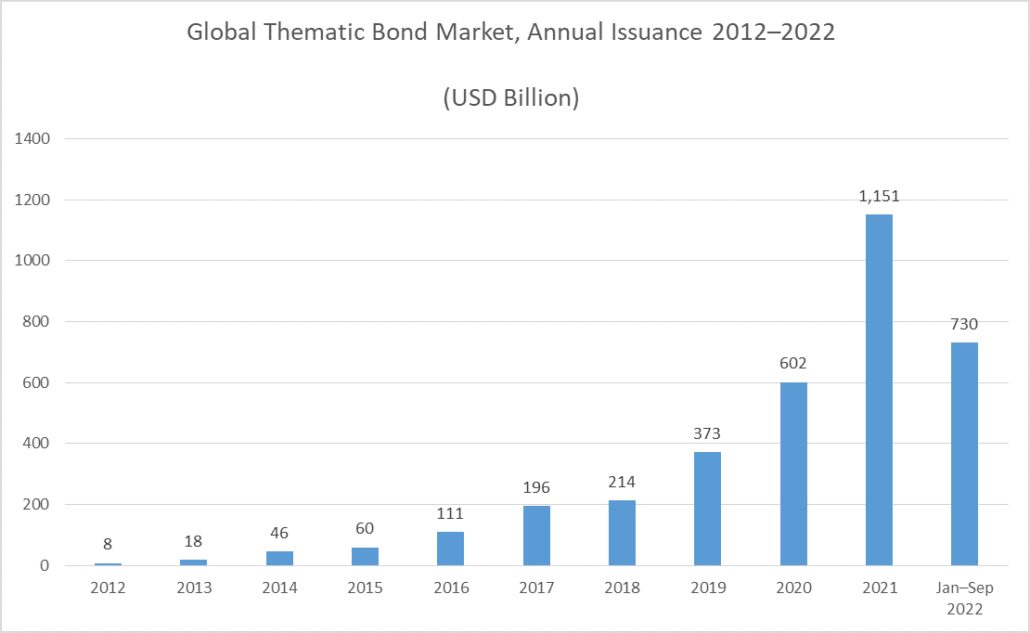

A longer term perspective of the thematic bonds issuance around the world can be referred to in figure 9.

Major issuers of GSS+ bonds by issuer type

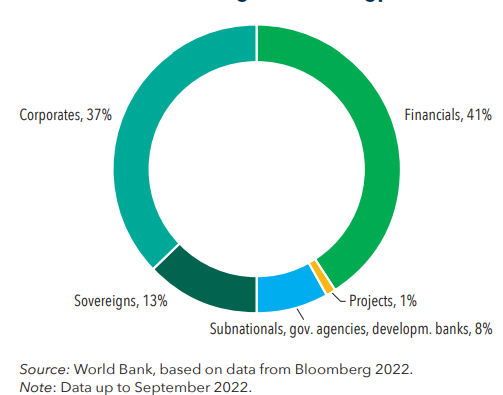

GSS+ bonds are being used as a means of raising sustainable finance by both sovereigns as well as private issuers. The financial institutions primarily dominate the thematic bonds issuances (41%), followed by the corporates (37%). The sovereign thematic bonds issuances by the public sector make up another 13% of the total amount issued. The regional and local governments, including the government agencies, and the development banks make up the remaining 8% of the total amount issued through GSS+ bonds, as on September, 2022 (refer figure 10).

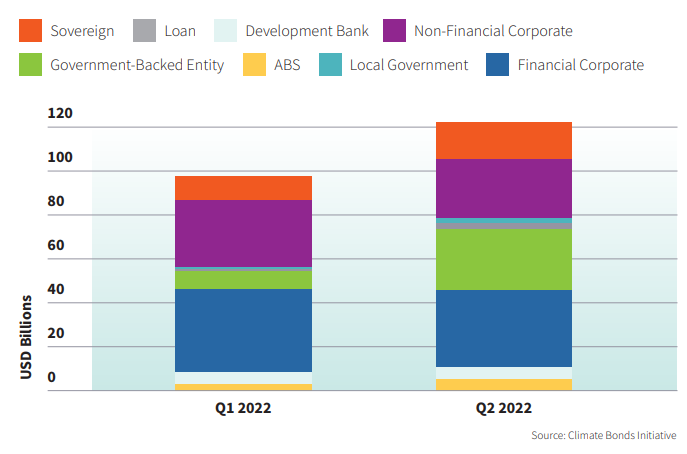

The review of the sustainable debt market during H1 2022 by Climate Bonds also highlights a similar trend, with the majority issuances brought in by the financial corporates, followed by the non-financial corporates (refer figure 11).

Sovereign issues vs private issuers

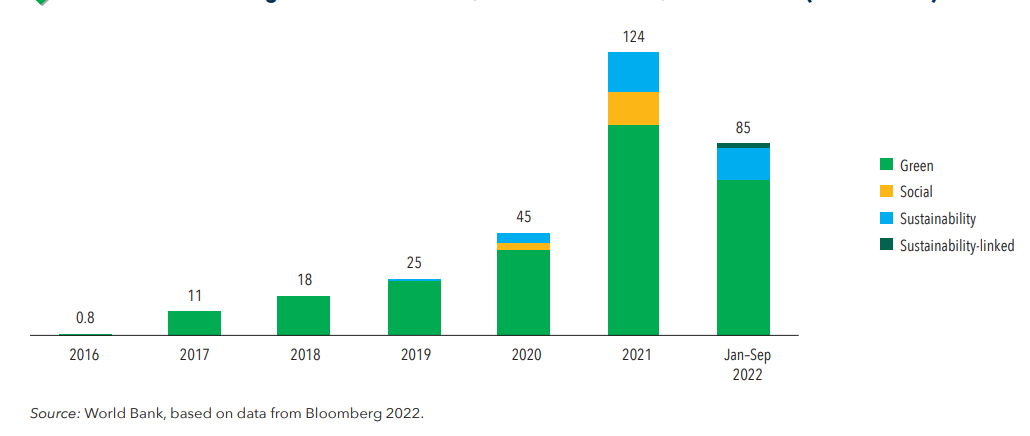

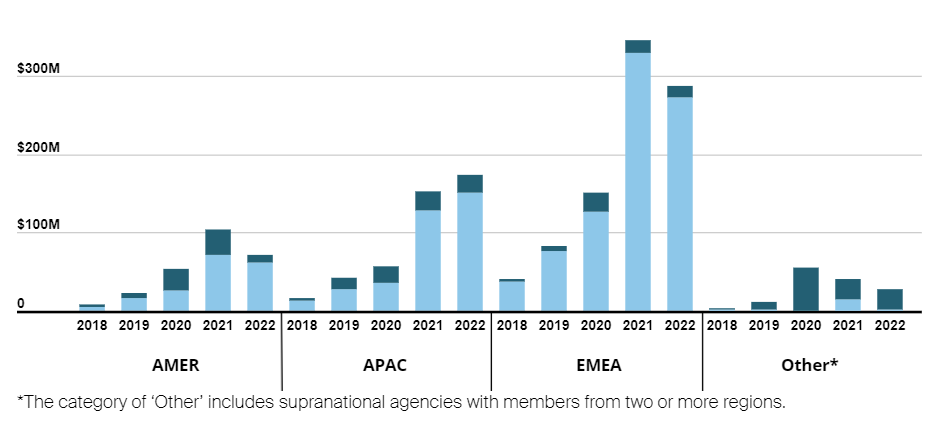

Of late, an increasingly visible trend is the entry of sovereign issuers in the GSS market, which have entered the fray late (Poland is arguably the first issuer, in 2016), and are still not a very large part of the entire landscape (about 7% by Sept., 2022); however, the volumes of sovereign issuance is growing quite fast (refer figure 12):

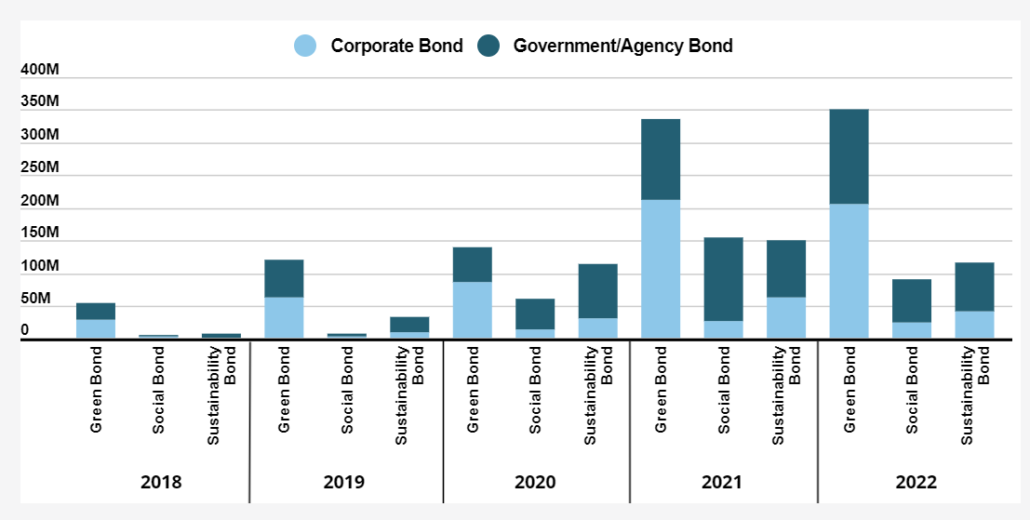

The Impact Report also provides some analytics on the volume of bonds issued by the sovereign vs corporates over a period of years, along with the type of GSS bonds issued (refer figure 13) –

Difficulties in sovereign issuance of thematic bonds

One of the difficulties in sovereign issuance of thematic bonds is that the monies raised by sovereigns are typically fungible and become a part of the consolidated funds raised by the issuer. However, with several countries over a period of time having come up with thematic bonds, there is a clear reporting requirement for the issuing sovereign to report the usage of the funds. For instance, in case of the Framework for Green Bonds issued by India, a Green Finance Working Committee (GFWC) has been constituted for the purpose of selection and evaluation of the green projects. The Public Debt Management Cell (PDMC) will keep a track of the proceeds of sovereign issuances, and monitor the allocations. All proceeds are required to be allocated to green bonds within two years from the date of issuance.

In many cases, apart from sovereign issuers, sub-sovereign and subnational issues have also issued thematic bonds.

Major jurisdictions

The major jurisdictions participating as issuers in the issuance of the GSS+ bonds included China, Germany, USA, Japan, European Union etc. Europe, Middle East and Africa (referred to as the “EMEA”) remained the major issuers during 2022 (details available upto Q3 of 2022), in terms of the region/ country contributing more than half of global issuance. While the sustainable bonds issuance witnessed a downfall during 2022, the Asia Pacific Region (referred to as “APAC”) remained the only issuers having an year-to-year growth of 13% in such issuances. As per the Impact Bond Report Q3 2022, China remains the largest issuing country of impact bonds, followed by Germany and France during the Q3 2022. The share of emerging markets is still quite small – about 15% of the total issuance.

GSS+ bonds in India

It is stated that Yes Bank brought the first issuance of green bonds in India in 2015. Climate Bonds Initiative’s India Sustainable Debt: State of the Market 2021 report[13] states that as of 31st Dec., 2021, the total amount of thematic bonds in India added USD 19.5 billion, comprising green bonds USD 18.3 billion, and USD 500 million each of sustainability and social bonds. This is from 75 issuances, both of which were issued in 2021. There was SLB issuance adding up to USD 1.2 billion too[14].

In terms of volumes over time scale, year 2021 at USD 7.5 billion was a record year for thematic bond issuances, with the volume being almost double of the previous all-time high in year 2017.

In terms of the types of issuers, 2021 was dominated by non-financial corporates. On a cumulative basis till end-2021, 40 out of 77 issuances, comprising nearly 75% of the total issuance so far, has come from non-financial entities. The predominance of non-financial issuers is understandable, as large entities go for transition into new sources of power, waste management, as also use of funds for EVs. Compared to the last significant year of issuance, viz., 2017, the number of financial sector entities issuing thematic bonds was quite limited.

The social bond issuance debuted in India in 2021, with the National Skill Development Corporation launching a USD14.4m ‘skill impact bond’ in October 2021[15].

Some of the large Indian issuers of GSS+ bonds include GreenCo, JSW Hydro Energy, Shriram Transport Finance Company, India Green Power Holdings, ReNew Power, Ultratech Cement Ltd etc. India has made a remarkable entry in the SLB market with Ultratech Cement Limited[16], issuing SLBs, thereby, being the first company in India and second in Asia to issue SLBs. The Company raised a total of 400 million USD equivalent to Rs. 2900 crores by way of issuance of such SLBs, listed on the Singapore Exchange Securities Trading Limited[17].

Much information is not available on the volume of GSS+ bonds issuance in the country during 2022. However, with the launch of the Sovereign Green Bond Framework[18] in November, 2022 followed by RBI’s press release on the issuance calendar, India is set to record a huge volume of green bond issuance in 2023, thereby, contributing towards a big chunk of GSS+ bonds. The start of 2023 will see the inaugural sovereign bond issuance, at USD 2 billion, from GoI.

Legal framework on GSS+ bonds in India

In India, the green bonds[19] are one of the most popular and recognised means of raising sustainable finance. SEBI, vide its circular dated May 30, 2017 had issued “Disclosure Requirements for Issuance and Listing of Green Debt Securities” in addition to the general requirements under the SEBI (Issue and Listing of Debt Securities) Regulations, 2008 (“ILDS Regulations, 2008”). The ILDS Regulations, 2008 was subsequently repealed by the SEBI (Issue and Listing of Non-Convertible Securities) Regulations, 2021 (“ILNCS Regulations, 2021”).

The ILNCS Regulations, 2021 defines the term “green debt security” as –

“a debt security issued for raising funds that are to be utilised for project(s) and/or asset(s)falling under any of the following categories,subject to the conditions as may be specified by the Board from time to time:

(i)Renewable and sustainable energy including wind, solar, bioenergy, other sources of energy which use clean technology,

(ii)Clean transportation including mass/public transportation,

(iii)Sustainable water management including clean and/or drinking water, water recycling,

(iv)Climate change adaptation,

(v)Energy efficiency including efficient and green buildings,

(vi)Sustainable waste management including recycling, waste to energy, efficient disposal of wastage,

(vii)Sustainable land use including sustainable forestry and agriculture, afforestation,

(viii)Biodiversity conservation,or

(ix)a category as may be specified by the Board, from time to time.”

Chapter IX of the Operational Circular in connection with the ILNCS Regulations, 2021 further prescribes the additional disclosures and responsibilities attracted on the issuer of green debt securities.

It may be noted that the aforementioned provisions are applicable only in case of issuance of listed green debt securities. It would not mean that the issuance of other forms of GSS+ bonds are prohibited, however, the same are not regulated by way of express provisions and the globally recognized voluntary principles apply on the same.

SEBI, vide its Consultation Paper on Green and Blue Bonds as a mode of Sustainable Finance, proposed amendments to the existing legal framework on issuance of green bonds to align the same with the updated GBP. It also seeks views on the introduction of the concept of colored bonds such as blue bonds for blue economy and yellow bonds for solar power in the existing legal framework. As discussed above, the ICMA recognises 4 sub-categories of green bonds. In this regard, the Consultation Paper seeks views on the sub-categorisation of existing “green bonds” in India, in line with the ICMA practices, as a means to avoid instances of “greenwashing”. Some of these recommendations has been adopted by SEBI in its board meeting dated 20th December, 2022, thereby, requiring amendments to the existing ILNCS Regulations, 2021. While the fine print of the amended text has not been notified yet, the amendments pertain to –

- enhancement of the scope of green debt securities and alignment of the same with the ICMA principles;

- introduction of the concept of blue bonds (related to water management and marine sector), yellow bonds (related to solar energy) and transition bonds as sub categories of green debt securities;

- specifications of basic dos and don’ts relating to green debt securities, to address issuers against ‘green-washing’ related risks.

The International Financial Service Centres Authority (Issuance and Listing of Securities) Regulations, 2021 (“IFSCA Regulations”) also provide a framework for listing of “ESG debt securities”, in line with the globally recognised principles.

Motivations for issuance of thematic bonds

Greenium or “green premium” is the premium, that is, the cost advantage that may be expected by the issuer of bonds, say, green bonds. ‘Greenium’ pricing may be defined as the difference in yield between thematic bonds and ordinary bonds of a similar maturity, based on the logic that investors are willing to pay extra for a bond with a sustainable impact[20].

A study[21] on the characteristics of green bonds with their brown counterparts, that is, having same characteristics and financial conditions, as near as possible, demonstrates that green bonds have higher yields, lower variance and more liquidity. The issuer’s reputation and existence of third-party verifications also contribute to the premium component.

To test green premium, Germany issued twin bonds in 2020, followed by Colombia.

UNDP puts before certain technical arguments towards the existence of “greenium”. The existence of the “sustainability factor” associated with the thematic bonds makes it “credit positive”, linked with the higher demand for such bonds and the willingness of the investors to accept a lower return for a thematic bond. The greenium is also associated with the increased flexibility that these bonds provide investors in the secondary market.

A 2021 report of Climate Bonds on the Green Bond Pricing in the Primary Market also evidences the existence of greenium with 26 out of 33 bonds issuances exhibiting a greenium. While there may be a greenium, presently, its extent is quite small: the average greenium for emerging market issuers was just about 3.4 basis points, on the basis of a 2021 study by Amundi and IFC[22].

Major motivations behind increased thematic bonds issuance include the following:

- Diversification of investor base: Issuing GSS+ bonds allows the issuer to tap into those funds or investors who have dedicated the whole or a part of their investible resources for ESG sensitive investments.

- Signalling commitment to sustainability: Particularly relevant for sovereign issues, issuing green or social bonds also signals the commitment of the country or the issuer to the cause of sustainability.

- Raising funds needed for investments for sustainability: This motivation is also particularly relevant for sovereign issuers. Many countries have fixed ambitious targets for achieving renewable energy penetration, reducing carbon emissions, etc. There are major investments required for the same: GSS bonds allow the countries to make such investments.

- Cheaper funding: There is some evidence of greenium, as discussed above.

On the other hand, issuance of green bonds entails additional costs and compliances. There is a clear governance process, monitoring of end use, etc. Currently, these costs seem to be outweighing the benefits – however, the commitment to sustainability seems to be having much better impact on issuers than the cost considerations.

Investor’s perspective on thematic bonds

The increased issuance of GSS+ bonds can be traced back to an increasing demand for the same amongst the investors. The investors’ growing interest in thematic bonds can either be “values”-driven or “value”-driven or both. While the investors, as part of their responsibility towards the society and environment, consider ESG in their investment analysis, that may not be the only reason investors are investing in GSS+ bonds. The long term perspective and the expectation of deriving great value from their investment portfolio is another major reason driving the investors’ growing demand for GSS+ bonds. The GSS+ bonds are considered as an opportunity to contribute to the transition to a low-carbon economy effectively and equitably.

The GSS+ investments are also significant in view of the long-term vision of the investors, since a company that addresses ESG issues effectively, is likely to sustain in the market for long-term. Therefore, while the investors are demonstrating their “values” and responsible behaviour by choosing the thematic bonds, they also have a “value” driven approach towards investments in these bonds.

Conclusion

Sustainable finance is as imperative as sustainable developments. Authors Schoenmaker and Willem Schramade highlight that the present economic model that the World is working on was developed during a period of abundancy. Natural resources were copious, and hence, classical economists propounded models that thrived on exploitation of natural resources. However, humanity has come to a stage where linear exploitation of natural resources will soon lead humanity to the brink of resource bankruptcy. As life has to move on beyond the lives of those who are living now, we soon need to redirect financial resources to sustainable development. Hence, sustainable financial instruments have become quintessential. The developments so far are encouraging, but too little for a lofty cause.

India, world’s fifth largest economy, is still way behind its peers when it comes to green and other sustainability instruments. However, with clearer green bond framework from SEBI, and the maiden issue of the GoI with USD 2 billion green bond issuance, there are strong signals.

Our resource center on ESG and other sustainability resources can be accessed here –

[1] Schoenmaker and Schramade, Principles of Sustainable Finance, Jan. 2019.

[2] Note the EU definition of “sustainable finance”: “Sustainable finance refers to the process of taking environmental, social and governance (ESG) considerations into account when making investment decisions in the financial sector, leading to more long-term investments in sustainable economic activities and projects. Environmental considerations might include climate change mitigation and adaptation, as well as the environment more broadly, for instance the preservation of biodiversity, pollution prevention and the circular economy. Social considerations could refer to issues of inequality, inclusiveness, labour relations, investment in human capital and communities, as well as human rights issues. The governance of public and private institutions – including management structures, employee relations and executive remuneration – plays a fundamental role in ensuring the inclusion of social and environmental considerations in the decision-making process.”

[3] “Thematic bonds include green, blue, social, gender, sustainability, and sustainability-linked bonds. These bonds are also collectively known as GSS; GSS+; environmental, social, and governance (ESG); or sustainable bonds.” – World Bank’s GSS Bonds survey at https://thedocs.worldbank.org/en/doc/4de3839b85c57eb958dd207fad132f8e-0340012022/original/WB-GSS-Bonds-Survey-Report.pdf

- [4] Green Bond Principles

- Social Bond Principles

- Sustainability Bond Guidelines

- Sustainability-linked Bond Principles

[5] https://www.icmagroup.org/assets/documents/Sustainable-finance/2022-updates/Green-Bond-Principles_June-2022-280622.pdf

[6] World Bank GSS Survey Report: https://thedocs.worldbank.org/en/doc/4de3839b85c57eb958dd207fad132f8e-0340012022/original/WB-GSS-Bonds-Survey-Report.pdf

[7] Refer The Social Bond market: towards a new asset class? by Impact Invest Lab – https://www.icmagroup.org/assets/documents/Regulatory/Green-Bonds/Public-research-resources/II-LAB2019-02Social-Bonds-130219.pdf

[8] https://www.climatebonds.net/files/reports/cbi_susdebtsum_h1_2022_02c.pdf

[9] For example, the SLBs issued by JSW Steel contains the condition of one time coupon step-up of 37.5bps if its performance does not achieve the SPT by FY30

[10] https://docs.londonstockexchange.com/sites/default/files/documents/sbm_factsheet_effective_as_at_19_february_2021.pdf

[11] https://oxfordbusinessgroup.com/news/transition-bonds-new-tool-fund-shift-towards-climate-sustainability

[12] https://www.climatebonds.net/transition-finance

[13] https://www.climatebonds.net/files/reports/cbi_india_sotm_2021_final.pdf

[14] The issuers included JSW Steel, UltraTech Cement, and Adani Electricity Mumbai Limited

[15] https://nsdcindia.org/sib

[16] See Page 4 of the Annual Report here

[17] Listing confirmation can be accessed here

[18] Our article on the same can be read at : India to bring its debutante sovereign green bond

[19] Our article on the same can be read here

[20] https://www.undp.org/blog/identifying-greenium

[21] See The Green Bonds Premium Puzzle: The Role of Issuer Characteristics and Third-Party Verification by Bachelet, Becchetti, and Manfredonia 2019

[22] https://www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/f68a35be-6b49-4a86-9d65-c02e411de48b/2022.06+-+Emerging+Market+Green+Bonds+Report+2021_VF+%282%29.pdf

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!