Ajay Kumar KV, Manager and Himanshu Dubey, Executive (corplaw@vinodkothari.com)

Introduction

The role or failure of independent directors in preventing corporate scandals became one of the central themes in corporate governance in India, and when SEBI issued a Consultation paper proposing a dual approval process for the appointment of independent directors, there was a substantial concern among leading companies in the country. Following discussions, the SEBI board has eventually decided to drop the proposal for dual approval, and instead, go for approval by a special majority. The decision of SEBI to not implement dual approval has not been appreciated by several commentators including Mr. Umakanth Varottil. Therefore, there is a sizzling controversy on the mode of appointment of independent directors.

In this article, we have made a comparison of the legislative framework for independent directors, especially the process of appointment, across various jurisdictions. While we note that some countries have moved to a dual approval process, the concept such as a database of IDs and a proficiency test remains an Indian aberration.

Independent Directors – Evolution in India

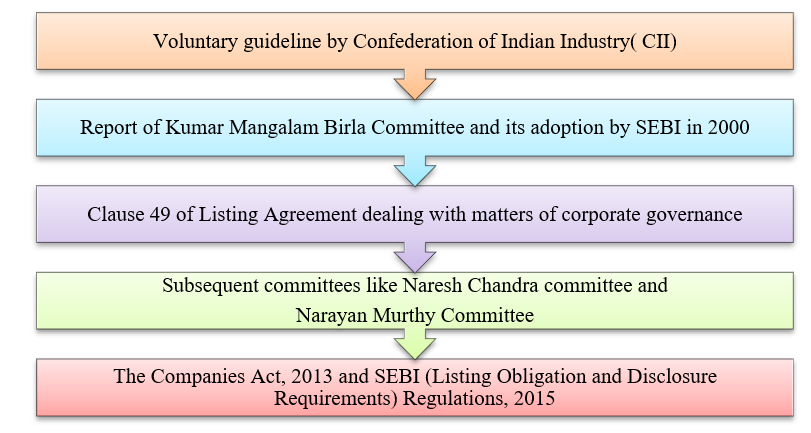

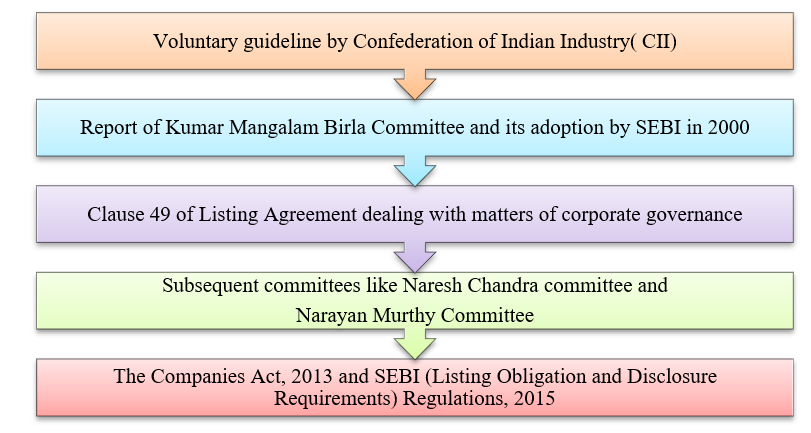

In India, the idea, or rather the need of having Independent Directors on the board of companies (especially those involving public interest) was acknowledged in the early 2000s through the SEBI Listing Agreement. Therefrom, the concept found a concrete legislative recognition in late 2013 as the Companies Act, 2013 took shape and character covering unlisted companies as well.

A snapshot of the concept’s evolution through guidelines and report to the Companies Act and SEBI (Listing Obligations and Disclosure Requirements) Regulations, 2015 is given below –

As compared to India, the western world was way ahead in the race- the concept of Independent Directors traces its inception as long back as in the 1950s when the murmurs of representation of small shareholders surrounded the corporate world. However, like in India, it took a long time for countries in Europe and North America to bring the concept within the regulatory framework. In the USA, the concept of Independent Director received regulatory recognition under the Sarbanes-Oxley Act, 2002. Thereafter the regulations issued by various stock exchanges took the lead.

Who is an Independent Director – The Indian Viewpoint

With all the hullabaloo about Independent Director, the natural question was ‘who is an independent director’; while the terminology was largely suggestive of the answer – “someone who is capable of putting forth an independent view about the business of the company”, it was crucial to define the term.

The definition of Independent Director from Section 149 of the Companies Act, 2013 (‘Act’) and Regulation 16 of the SEBI (Listing Obligations and Disclosure Requirements) Regulations, 2015 (‘LODR’). While unlisted companies are required to adhere to the requirement under section 149 of the Act; listed companies or those intending to be listed are required to abide by LODR too.

On the same lines as discussed above, LODR identifies an independent director as someone who is not related to the company, either as a promoter or director of the company, its group companies, who do not have a material pecuniary relationship with the company or its group, as well as someone who does not or has not been related to the company in any manner in the recent position, such that s/he could influence the decisions/ business of the company.

The aforesaid is provided in Regulation 16 of LODR[1], which defines “Independent Director” as “a non-executive director, other than a nominee director of the listed entity, who:

- who, in the opinion of the board of directors, is a person of integrity and possesses relevant expertise and experience;

- who is or was not a promoter of the listed entity or its holding, subsidiary or associate company or member of the promoter group of the listed entity;

- who is not related to promoters or directors in the listed entity, its holding, subsidiary, or associate company;

- who, apart from receiving director’s remuneration, has or had no material pecuniary relationship with the listed entity, its holding, subsidiary or associate company, or their promoters, or directors, during the [three]* immediately preceding financial years or during the current financial year

- none of whose relatives ;

[(A) is holding securities of or interest in the listed entity, its holding, subsidiary or associate company during the three immediately preceding financial years or during the current financial year of face value in excess of fifty lakh rupees or two percent of the paid-up capital of the listed entity, its holding, subsidiary or associate company, respectively, or such higher sum as may be specified;

(B) is indebted to the listed entity, its holding, subsidiary or associate company or their promoters or directors, in excess of such amount as may be specified during the three immediately preceding financial years or during the current financial year;

(C) has given a guarantee or provided any security in connection with the indebtedness of any third person to the listed entity, its holding, subsidiary or associate company or their promoters or directors, for such amount as may be specified during the three immediately preceding financial years or during the current financial year; or

(D) has any other pecuniary transaction or relationship with the listed entity, its holding, subsidiary or associate company amounting to two percent or more of its gross turnover or total income:

Provided that the pecuniary relationship or transaction with the listed entity, its holding, subsidiary or associate company or their promoters, or directors in relation to points (A) to (D) above shall not exceed two percent of its gross turnover or total income or fifty lakh rupees or such higher amount as may be specified from time to time, whichever is lower;]*

- who, neither himself/herself nor whose relative(s) —

- holds or has held the position of a key managerial personnel or is or has been an employee of the listed entity or its holding, subsidiary, or associate company [or any company belonging to the promoter group of the listed entity]* in any of the three financial years immediately preceding the financial year in which he is proposed to be appointed;

[Provided that in case of a relative, who is an employee other than key managerial personnel, the restriction under this clause shall not apply for his / her employment.]*

- is or has been an employee or proprietor or a partner, in any of the three financial years immediately preceding the financial year in which he is proposed to be appointed, of —

- a firm of auditors or company secretaries in practice or cost auditors of the listed entity or its holding, subsidiary, or associate company; or

- any legal or a consulting firm that has or had any transaction with the listed entity, its holding, subsidiary, or associate company amounting to ten percent or more of the gross turnover of such firm;

- holds together with his relatives two percent or more of the total voting power of the listed entity; or

- is a chief executive or director, by whatever name called, of any non-profit organisation that receives twenty-five percent or more of its receipts or corpus from the listed entity, any of its promoters, directors or its holding, subsidiary or associate company or that holds two percent or more of the total voting power of the listed entity;

- is a material supplier, service provider or customer or a lessor or lessee of the listed entity;

- who is not less than 21 years of age.

- who is not a non-independent director of another company on the board of which any non-independent director of the listed entity is an independent director

Evidently, the definition in India is very comprehensive compared to other major jurisdictions. Below we discuss and compare some major provisions in the definition of IDs in India, the USA and the UK –

| Basis |

India |

USA[2] |

UK[3] |

| Material relationship |

The director shall, apart from receiving director’s remuneration, has or had no material pecuniary relationship with the listed entity, its holding, subsidiary or associate company, or their promoters, or directors, during the three immediately preceding financial years or during the current financial year;

None of the director’s relatives

[(A)is holding securities of or interest in the listed entity, its holding, subsidiary or associate company during the three immediately preceding financial years or during the current financial year of face value in excess of fifty lakh rupees or two percent of the paid-up capital of the listed entity, its holding, subsidiary or associate company, respectively, or such higher sum as may be specified;

(B) is indebted to the listed entity, its holding, subsidiary or associate company or their promoters or directors, in excess of such amount as may be specified during the three immediately preceding financial years or during the current financial year;

(C) has given a guarantee or provided any security in connection with the indebtedness of any third person to the listed entity, its holding, subsidiary or associate company or their promoters or directors, for such amount as may be specified during the three immediately preceding financial years or during the current financial year; or

(D) has any other pecuniary transaction or relationship with the listed entity, its holding, subsidiary or associate company amounting to two percent or more of its gross turnover or total income:

Provided that the pecuniary relationship or transaction with the listed entity, its holding, subsidiary or associate company or their promoters, or directors in relation to points (A) to (D) above shall not exceed two percent of its gross turnover or total income or fifty lakh rupees or such higher amount as may be specified from time to time, whichever is lower;]* |

The director qualifies as “independent” unless the board of directors affirmatively determines that the director has no material relationship with the listed company (either directly or as a partner, shareholder, or officer of an organization that has a relationship with the company).

The references to “listed company” would include any parent or subsidiary in a consolidated group with the listed company |

The director has, or had within the last three years, no material business relationship with the company, either directly or as a partner, shareholder, director or senior employee of a body that has such a relationship with the company;

The director has not received or receives additional remuneration from the company apart from a director’s fee, participates in the company’s share option or a performance-related pay scheme, or is a member of the company’s pension scheme |

| Employment |

The director neither himself/herself nor his relatives hold or has held the position of a key managerial personnel or is or has been an employee of the listed entity or its holding, subsidiary or associate company, [or any company belonging to the promoter group of the listed entity]* in any of the three financial years immediately preceding the financial year in which he is proposed to be appointed.

[Provided that in case of a relative, who is an employee other than key managerial personnel, the restriction under this clause shall not apply for his / her employment]*

|

The director is not independent if the director is, or has been within the last three years, an employee of the listed company or an immediate family member is, or has been within the last three years, an executive officer, of the listed company.

The director has received or has an immediate family member who has received, during any twelve-month period within the last three years, more than $120,000 indirect compensation from the listed company, other than director and committee fees and pension or other forms of deferred compensation for prior service (provided such compensation is not contingent in any way on continued service). |

The director neither is or has been an employee of the company or group within the last five years |

| Promoter/director or related to them |

The director is or was not a promoter of the listed entity or its holding, subsidiary or associate company or member of the promoter group of the listed entity;

Who is not related to promoters or directors in the listed entity, its holding, subsidiary, or associate company;

|

No director qualifies as “independent” unless the board of directors affirmatively determines that the director has no material relationship with the listed company either directly or as a partner, shareholder, or officer of an organization that has a relationship with the company. |

The director has close family ties with any of the company’s advisers, directors, or senior employees. |

| Cross-directorship |

The director is not a non-independent director of another company on the board of which any non-independent director of the listed entity is an independent director

|

The director or an immediate family member is or has been with the last three years, employed as an executive officer of another company where any of the listed company’s present executive officers at the same time serves or served on that company’s compensation committee. |

The director holds cross-directorships or has significant links with other directors through involvement in other companies or bodies |

One may find many similarities in the definition of IDs in foreign jurisdictions with that in India but as already mentioned above, the definition in India is one of the most comprehensive and meticulous ones.

Appointment/reappointment process of IDs in different jurisdictions

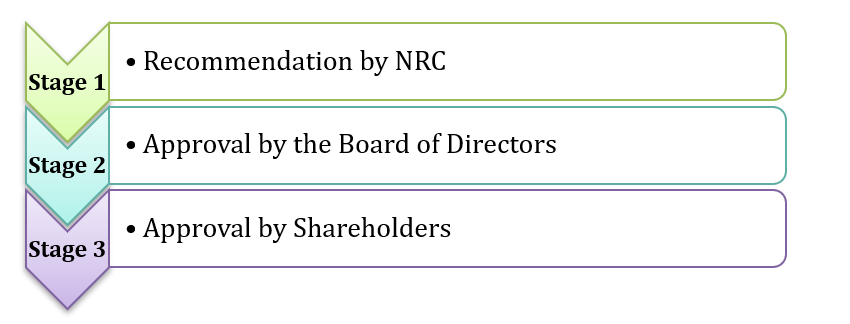

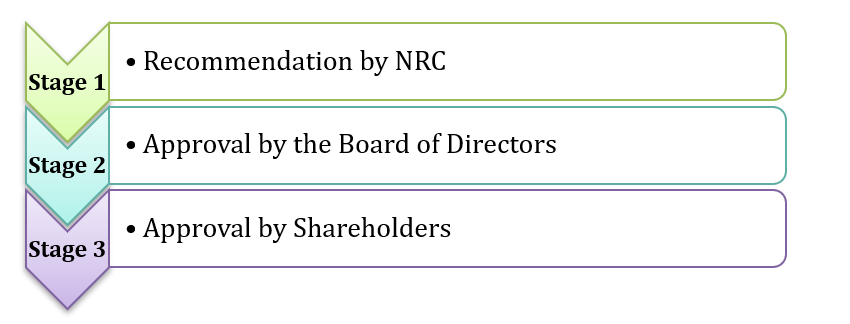

In India, the extant provisions require ordinary resolution to be passed by the shareholders for the appointment of IDs and a special resolution in case of re-appointment, based on the recommendation of the Nomination and Remuneration Committee (NRC) and the approval of the Board.

Earlier, SEBI had released a consultation paper w.r.t. regulatory provisions for Independent Directors which warranted a ‘dual approval’ for such appointment/ re-appointment as follows:

- An ordinary resolution by shareholders (Special Resolution in case of re-appointment) and

- A resolution by “majority of minority”

(Note: The Paper defined minority shareholders to mean shareholders other than the promoter and promoter group.)

However, owing to the response received thereafter, SEBI, in its Board Meeting held on June 29, 2021[4] (SEBI Board Meeting), disregarded the earlier proposal of a dual approval and instead decided that the approval of shareholders would be required by way of special resolution for both appointment and re-appointment

[SEBI, vide (Listing Obligations and Disclosure Requirements) (Third Amendment) Regulations, 2021 ( ‘Amendments’) notified on August 4, 2021, have amended the Regulation 25 providing that the appointment, re-appointment or removal of an independent director of a listed entity, shall be subject to the approval of shareholders by way of a special resolution. Thus, listed entities henceforth shall have to obtain the approval of members via a special resolution for the appointment as well.]*

In the USA, the NASDAQ Listing Rules provide that, where shareholders’ approval is required, the minimum vote that will constitute shareholder approval shall be a majority of the total votes cast on the proposal.

Akin to the NRC in India, the UK Corporate Governance Code of 2018 requires that the Board should establish a Nomination Committee, composed of majority independent non-executive directors, to lead the process for the appointment of all directors. Any appointment must be approved by the Board and shareholders of the company by way of an ordinary resolution.

However, as per the UK Listing Rules, the appointment of IDs is dependent on the existence of a controlling shareholding[5]. A snapshot of the manner of appointment is given below

Hence, approval is required from both the set of shareholders. If the company still proposes to appoint the same person as an independent director despite failing to receive the dual nod as discussed above, it can propose another resolution to elect the same person, but after 90 days from the date when the previous proposal was put to vote. This time the resolution will only require approval by the shareholders of the company[6].

Databank of Independent Directors & the Online Proficiency Test

One of the prerequisites to become an Independent Director in India is the inclusion of their name in the Databank of Independent Directors (‘Databank’) and passing an Online Proficiency Test (‘Test’) within a period of two years from the date of inclusion of name in the databank as per Section 150 of the Act, read with Rule 6 of the Companies (Appointment and Qualification of Directors) Rules, 2014. However, certain categories of persons have been exempted[7] from the requirement of passing the Test who possess requisite experience and expertise as prescribed;

The question, however, is whether such arduous and tedious criteria required for an appointment really ensure board independence and good governance practices. It is understood that the tenet behind such steps was quality control – it was to ensure that only persons with a certain minimum level of expertise & experience are appointed as Independent Directors.

Further, some previous instances of celebrity directorships were also to be discouraged since the role of IDs is to ensure good governance practices and upholding the interest of all the stakeholders as a whole including minority stakeholders. Therefore, it should not merely be used as a tool of publicity.

However, keeping in mind the seniority of the position of directors in companies as well as lack of precedent, the requirement of passing the test seems rather odd and brings anomalies in the IDs’ regulatory regime in India vis-à-vis the rest of the world.

Constituted Body for selection of candidates for the role of IDs

As per the extant laws in India, the NRC recommends the persons to be appointed as IDs on the board of the company. This committee oversees the functions of formulation and recommendation of remuneration of the directors and the senior management. It has been decided in the SEBI Board Meeting that the process to be followed by NRC while selecting candidates for appointment as IDs, shall be elaborated and be made more transparent including enhanced disclosures regarding the skills required for appointment as an ID and how the proposed candidate fits into that skillset.

[SEBI, via the Amendments, has added a new sub-clause after sub-clause (1) in Para A in Part D of Schedule II for implementing its decision on an elobaroted and transparent selection oricess of IDs.

The NRC of every listed entities shall, for every appointment of IDs,

- evaluate the balance of skills, knowledge and experience on the Board and on the basis of such evaluation

- prepare a description of the role and capabilities required of IDs.

- ensure that the person recommended to the Board for appointment as an ID has the capabilities identified in such description.

For the purpose of identifying suitable candidates, the Committee may:

- use the services of an external agencies, if required;

- consider candidates from a wide range of backgrounds, having due regard to diversity; and

- consider the time commitments of the candidates

Thus, the NRCs of every listed company henceforth has to first formulate the description of the role of an ID after considering the skill sets and knowledge and experience required for acting as an ID of the company. This has also widened the scope of NRC as well as the responsibility for finding the right candidate for the position of an ID. The extant practice was to give disclosures in Corporate Governance Report and the Board report that forms part of the Annual Report of the Company.]*

Just like the NRC in India, companies in the USA have to constitute Compensation Committee as per the NASDAQ Stock Market LLC Rules [5605. Board of Directors and Committees] “Each Company must have, and certify that it has and will continue to have, a compensation committee of at least two members. Each committee member must be an Independent Director as defined under Rule 5605(a) (2).”

As per the NASDAQ Rules, director nominees must either be selected, or recommended for the Board’s selection, either by:

- Independent Directors constituting a majority of the Board’s Independent Directors in a vote in which only Independent Directors participate, or

- a nominations committee composed solely of Independent Directors.

The New York Stock Exchange Listed Company Manual (‘NYSE Manual’) vests on the nominating/corporate governance committee, the sole authority to retain and/or terminate any search firm to be used to identify director candidates, including sole authority to approve the search firm’s fees and other retention terms.

The UK Corporate Governance Code, 2018 states that the board should establish a remuneration committee of independent non-executive directors, with a minimum membership of three, or in the case of smaller companies, two. In addition, the chair of the board can only be a member if they were independent on appointment and cannot chair the committee. Before appointment as chair of the remuneration committee, the appointee should have served on a remuneration committee for at least 12 months.

Tenure and re-appointment of IDs

In India, one term of appointment of IDs is for a maximum of 5 years and can be re-appointed for another term. Such re-appointment has to be made by way of passing a special resolution. Further, the performance of Independent Directors is to be evaluated every year based on which the NRC recommends whether the said director shall be re-appointed or not. However, the question of such recommendation only comes when the tenure of the director comes to its end.

Furthermore, the UK Corporate Governance Code provides that all directors should be subject to annual re-election. The code also considers the presence of an ID for more than nine years on the Board of a company as a threat to his independence.

In Singapore, Rule 720(5) of the SGX Listing Rules (Mainboard) / Rule 720(4) of the SGX Listing Rules (Catalist)[8] requires all directors to submit themselves for re-nomination and re-election at least once every three years.

The rule requires a re-nomination & re-election of all directors of the company at least once in 3 years and it helps to ensure that the assessment of independence happens once in every 3 years by members.

Cooling-off Period for appointment/reappointment of IDs

In India, a cooling-off period of 2 years is required in case of any material pecuniary transactions between a person or his/her relative and the listed entity or its holding, subsidiary, or associate company. The LODR has prescribed a cooling-off period of three years for Key Managerial Personnel (and their relatives) or employees of the promoter group companies, for appointment as an ID in the listed entity. However, relatives of employees of the company, its holding, subsidiary, or associate company have been permitted to become IDs, without the requirement of a cooling-off period, in line with the Companies Act, 2013.

[SEBI via Amendments has provided that an ID who resigns from a listed entity, shall not be appointed as an executive / whole time director on the board of the listed entity, its holding, subsidiary or associate company or on the board of a company belonging to its promoter group, unless one year has elapsed from the date of resignation.]*

The NASDAQ Stock Market LLC Rules[9] (‘NASDAQ Rules’) have prescribed a cooling-off period of 3 years for the appointment of an independent director where such person has a relationship with the company as prescribed under the rule.

UK Corporate Governance Code, 2018[10] (‘UK Code’) provides that a person who has or had within the last three years, a material business relationship with the company, either directly or as a partner, shareholder, director, or senior employee of a body that has such a relationship with the company shall not be appointed as an Independent Director.

The Singapore Code of Corporate Governance, 2018[11] prescribes a cooling-off period of 3 years for the appointment of an independent director where such person has a relationship with the company.

Remuneration of Independent Directors

In India, offering stock options to Independent Directors is prohibited. On the contrary, as per the New York Stock Exchange Listed Company Manual (‘NYSE Manual’), Independent directors must not accept any consulting, advisory, or other compensatory fees from the Company other than for board service.

Further, the UK Corporate Governance Code 2018 provides that remuneration for all non-executive directors should not include share options or other performance-related elements. Independent directors shall not be a member of the company’s pension scheme.

The Singapore Code of Corporate Governance 2018 the Remuneration Committee should also consider implementing schemes to encourage non-executive directors (NEDs) to hold shares in the company so as to better align the interests of such NEDs with the interests of shareholders. However, NEDs should not be over-compensated to the extent that their independence may be compromised.

Fees payable to non-executive directors shall be by a fixed sum, and not by a commission on or a percentage of profits or turnover. (Appendix 2.2 Articles of Association)

Important determinants of Independence across jurisdictions

| Determinants of Independence |

India |

USA |

UK |

Singapore |

| Present or past employment relationship |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Relationship of close family members |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Pecuniary relationship with company* |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Cooling-off period |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Restriction on Stock options |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

| ID databank & Proficiency test |

Yes |

No |

No |

No |

* Subject to specific monetary limits

Conclusion

The regulatory framework for Independent Directors in India has a lot of things in common with other jurisdictions around the world. However, the requirement of passing an online test for becoming eligible to be appointed as an Independent Director is something peculiar to India. The regulators across jurisdictions have been proactive in bringing changes to the Independent Director regime, to strengthen the corporate governance in listed companies. One may expect some of the above discussed benchmark practices in different foreign jurisdictions may soon be adopted in India as well.

Related presentation – https://vinodkothari.com/2021/08/ensuring-board-continuity-and-balance-of-capabilities/

[1] https://www.sebi.gov.in/legal/regulations/sep-2015/securities-and-exchange-board-of-india-listing-obligations-and-disclosure-requirement-regulations-2015-last-amended-on-may-5-2021-_37269.html

[2] https://nyse.wolterskluwer.cloud/listed-company-manual

[3]https://www.frc.org.uk/getattachment/88bd8c45-50ea-4841-95b0-d2f4f48069a2/2018-UK-Corporate-Governance-Code-FINAL.PDF

[4] https://www.sebi.gov.in/media/press-releases/jun-2021/sebi-board-meeting_50771.html

[5] A company is said to have controlling shareholder(s) if a shareholder/ an entity/ a group holds more than 30% voting power in the company

[6] https://www.mondaq.com/uk/acquisition-financelbosmbos/315598/new-dual-process-for-appointing-independent-directors-amendments-to-articles-of-association

[7] https://www.independentdirectorsdatabank.in/pdf/databank-rules/FifthAmdtRules_18122020.pdf

[8] https://rulebook.sgx.com/rulebook/board-matters-1

[9] https://listingcenter.nasdaq.com/rulebook/nasdaq/rules

[10] https://www.frc.org.uk/getattachment/88bd8c45-50ea-4841-95b0-d2f4f48069a2/2018-UK-Corporate-Governance-Code-FINAL.PD

[11] https://www.mas.gov.sg/-/media/MAS/Regulations-and-Financial-Stability/Regulatory-and-Supervisory-Framework/Corporate-Governance-of-Listed-Companies/Code-of-Corporate-Governance-6-Aug-2018.pdf

*[ The changes are applicable with effect from 1st January, 2022].