The ‘net concentrate’ of ‘preference- Key takeaways from the SC ruling regarding preferential transactions

-Sikha Bansal

The Hon’ble Supreme Court’s ruling in Jaypee [Civil Appeal Nos. 8512-8527 of 2019] stands as a landmark for two reasons – first, it deals with an otherwise unexplored periphery of vulnerable transactions in the context of insolvency, and secondly, it will have far-reaching impacts on how secured transactions are structured and the manner in which the lenders lend.

Precisely speaking, where the subsidiary gave its properties as security for loans and advances availed by the holding, looking into the facts and circumstances and the relationship between the parties, the SC held the transaction to be a preferential transaction hit by section 43 of the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016 (IBC). The SC, however, did not go into question of whether the transactions were undervalued or fraudulent as the arena and scope of requisite enquiries are entirely different. Simultaneously, the SC held that the lenders may though be secured, but are only ‘indirect’ secured lenders, and cannot be called financial creditors of the subsidiary.

In essence, the SC has partly upheld the verdict of NCLT, which the author has discussed in an earlier article. In yet another article, I have studied some pertinent aspects of vulnerable transactions in the light of global provisions and case precedents. In this quick article, I discuss prominent observations of and key takeaways from the SC ruling as also the implications thereof, without getting into elaborate discussions made by Hon’ble SC as to meaning and connotations of ‘preference’.

Net concentrate of preference

Implications of a transaction by a solvent entity is essentially different from that by an insolvent entity. As also noted by SC, given a wide range of stakeholders of a corporate structure, where the corporate person is in crisis, where either insolvency resolution is to take place or liquidation is imminent, the transactions by such corporate person are under scanner. Any such transaction which has “an adverse bearing on the financial health of the distressed corporate person or turns the scales in favour of one or a few of its creditors or third parties, at the cost of the other stakeholders, has always been viewed with considerable disfavor.”

As such, the law has created deeming fiction for the purpose of section 43, “intent” not being an essential ingredient. If the conditions under section 43 are met, the corporate debtor shall be deemed to have given preference at a relevant time. A transaction which has characteristics enumerated in sub-sections (2) and (4), is presumed to be preferential transactions, even though it may not be so in reality and irrespective whether the transaction was in fact intended or even anticipated to be so.

In the instant case, the creation of security interest by the subsidiary was for the benefit of the holding. The holding even though was an operational creditor of the subsidiary, was put in an advantageous position such that its own liability towards its creditors shall be reduced. As a corollary, the creditors of the subsidiary would suffer disadvantage by losing access to the assets, otherwise includible in the estate of the subsidiary. Hence, the preference was to a related party, and therefore, the look-back period would be two years.

As regards the ‘ordinary course of business’ exception, the SC held that for the purpose of section 43, the conduct and affairs of the corporate debtor are to be examined, and not the ordinary course of business or financial affairs of the transferee alone. While furnishing a security may be one of the normal business practices, it would become part of ‘ordinary course of business’ only if it falls in place as a part of the undistinguished common flow of business done, and is not arising out of any special or particular situation.

One of the contentions of the lenders of the holding was that the transactions could not be regarded as fresh mortgage, but only a ‘re-mortgage’ as most of the properties had already been mortgaged with the respective lenders. The SC rejected the contention observing that the so-called ‘re-mortgage’, on all its legal effects and connotations, could only be regarded as a fresh mortgage, and that “it obviously befalls on the mortgagor to consider at the time of creating any fresh mortgage as whether such a transaction is expedient and whether it should be entered into at all”.

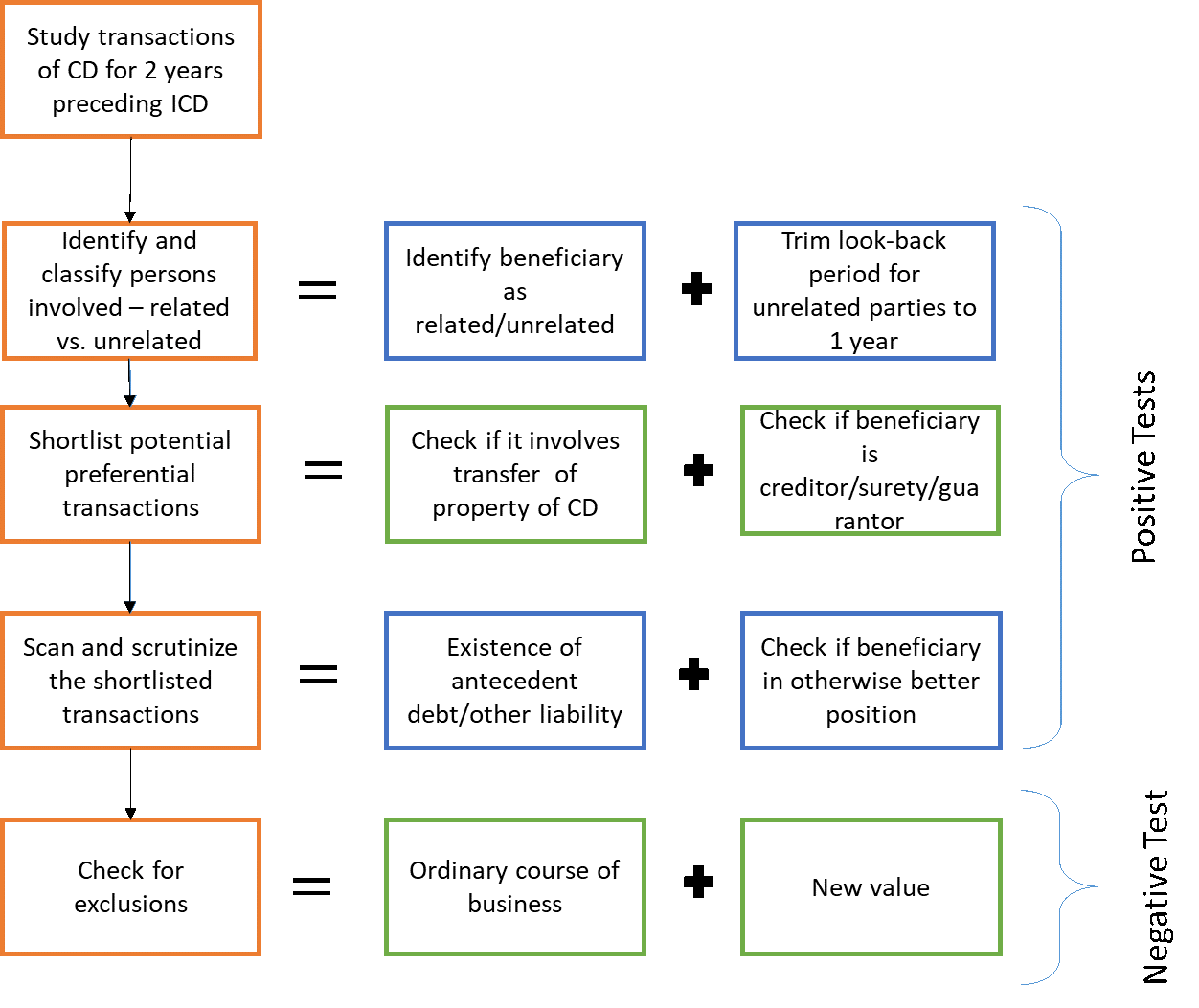

Besides, the SC gave an illustrative guide to section 43, as to how a resolution professional can proceed to act with reasonable clarity and less confusion. The steps are indicated figuratively

Indirect secured creditors but not financial creditors

The basic element for classification as ‘financial debt’ is that the money must be disbursed against time value of money. The word ‘includes’ cannot be so pervasive so as to evade the implications of the word ‘means’ in section 5(8), that is, the definition of ‘financial debt’. Thus, a mortgage cannot be equated to an indemnity/guarantee. For a person to be considered a financial creditor of the corporate debtor, it has to be shown that the corporate debtor owes a financial debt to such person. What is intended by the expression ‘financial creditor’ is a person who has direct engagement in the functioning of the corporate debtor; who is involved right from the beginning while assessing the viability of the corporate debtor; who would engage in restructuring of the loan as well as in reorganisation of the corporate debtor’s business when there is financial stress. Therefore, a third party to whom the corporate debtor does not owe a financial debt cannot become its financial creditor.

Therefore, as held by SC, a creditor having only security over the assets of the corporate debtor (third party securities) may only be called a secured creditor but not financial creditor. Such mortgage debt may well be a ‘debt’ but cannot partake the character of a ‘financial debt’. Hence, the mortgagee lenders of the holding cannot be categorized as financial creditors of the subsidiary.

The SC, while dealing with the commercial practice of taking third-party security, emphasized on the importance of ‘due diligence’ by lenders. The lenders should ensure that the security is genuine and adequate. The lenders must prefer a ‘clean’ security to justify the transaction as being in the ordinary course of business. As regards third party security, the same must be a prudent and viable one and should not be likely to be hit by any law. The lenders, therefore, remain under obligation to assure themselves that the third party is not already indebted or in red and is not likely to fail in dealing with its own indebtedness.

Notably, the observations of SC are independent of whether the transactions are preferential or not. Hence, the ratio would apply even if third party securities have been given in ordinary course of business, or say for new value. This dicta may have wide-ranging ramifications and, and in humble views of the author, might result in anomalies.

When a corporate entity goes into insolvency, a person who has taken bona fide third party security from such entity against loans/advances to another person, then according to the proposition, the person will be left in a lurch as –

- (i) it will not be possible for the lender to enforce the security interest because of imposition of moratorium,

- (ii) the lender cannot qualify as financial creditor and thus, cannot have a seat at committee of creditors, and decide on resolution/liquidation of the corporate debtor,

- (iii) though the SC has not dealt with the question of priority of such lenders, yet deciphering the ruling, it seems that such lender has been considered as only indirect secured creditor, and hence, it will not be possible for the lender to claim priority status under section 53 (though the law does not make any reference to direct versus indirect secured creditor).

Therefore, a mere lack of direct relationship between the lender and the security-provider will render the entire exercise of ‘security creation’ as nugatory, where the security-provider goes into insolvency. We may call it a gap in the law or a matter of interpretation; however, the practical difficulties arising out of the proposition cannot be disregarded.

Concluding remarks

The SC ruling is an elaborate guide to understanding preferential transactions, while the court has deferred discussion on undervalued and fraudulent transactions to be examined in an appropriate case. However, the classification of lenders as ‘secured’, but not ‘financial’ creditors may throw open a lot of questions as well as practical difficulties as pointed above. As to what recourse such lenders may have, there is no possibility of enforcing the security interest (independent of whether the transaction is a voidable one or not); hence, the only option before the lenders is to proceed against the debtor to which the loans/advances were given.

Readers may refer:

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!