Cross Border Insolvency in India: A Long Due Dream

- Neha Malu & Shreyan Srivastava (resolution@vinodkothari.com)

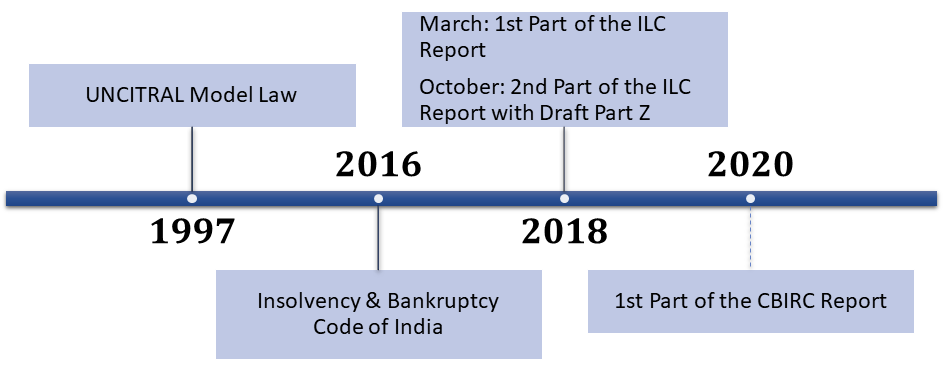

Five years since its commencement, the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016 has seen a paradigm shift vis-à-vis its nascent stage – on-field challenges, as and when faced, have been attempted to be tackled either by way of amendments or judicial precedents. However, the legal position with respect to Cross Border Insolvency has stagnantly remained in the discussion stage. Despite significant steps since 2018, the Indian regime still lacks a comprehensive set of laws dealing with the same.

The Economic Survey 2021-22[1] also observed that ‘at present, Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016 (IBC) provides for the domestic laws for the handling of an insolvent enterprise. IBC at present has no standard instrument to restructure the firms involving cross border jurisdictions. Presently, while foreign creditors can make claims against a domestic company, the IBC currently does not allow for automatic recognition of any insolvency proceedings in other countries[2]’

On the similar lines, the Union Budget 2022-23[3], has also proposed that “Necessary amendments in the Code will be carried out to enhance the efficacy of the resolution process and facilitate cross border insolvency resolution.”[4] It is understood that the foreseeable amendments would be in line with the draft regulations introduced in the Draft Part Z. In this article, the authors discuss the Draft Regulations circulated by the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Board of India (‘IBBI’), in light of the several reports issued by the Indian committees.

Background:

The rapidly growing and globalising corporate world has given birth to multinational entities that surpass national boundaries, creating an almost borderless relation among several businesses. Almost every country has commercial relations that extend beyond one or more jurisdictions and consequently have debtors and creditors located at various such locations. As a result, if a multinational company were to undergo insolvency, the overlapping and differing legislative proceedings of multiple jurisdictions (where such creditors and debtors are present) makes the entire process entirely impossible.

Cross border insolvency deals with the circumstances where the insolvent debtor has assets and creditors in multiple countries or when insolvency proceedings have been initiated against the insolvent debtor in multiple countries. In India, to review and assess the functioning and implementation of the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016 (“IBC”), the Insolvency Law Committee (“ILC”) was constituted by the Ministry of Corporate Affairs. The ILC in its Report proposed to re-evaluate the current insolvency framework in India because it was not at par with the Global Standards and adopt the UNCITRAL Model Law on Cross-Border Insolvency (“Model Law”) to resolve the concerns relating to cross-border insolvency in India.

Literature review:

Taking into consideration the contributions of Kent Anderson with E.S. Adams and J.K. Fincke we can formulate five general models or approaches towards cross-border insolvencies:[5]

- Territorialism: Administration of domestic assets under domestic law for the exclusive benefit of domestic creditors.

- Pure Universalism: Administration of national and foreign assets under a single domestic law for the benefit of national and foreign creditors.

- Modified Universalism: Administration of national and foreign assets under multiple laws coordinating through cooperation based on location of creditors benefit of national and foreign creditors.

- Secondary insolvency: Administration of national and foreign assets under domestic law for domestic creditors first followed by those of foreign creditors through cooperation.

- Corporate-charter Contractualism: It allows the debtor to select a prior jurisdiction for filing for bankruptcy. However, such an approach suffers from enforcement as such jurisdictions may refuse to acknowledge such an approach.

Foreign & National Cross-Border Insolvency

In one of the first transnational insolvency case of Maxwell Communications Corporation (“MCC”),[6] the corporate debtor company’s “seat” was in England but had several other operating companies in the United States. Cross-border insolvency deals with the circumstances where the insolvent debtor has assets and creditors in multiple countries or when insolvency proceedings have been initiated against the insolvent debtor in multiple countries. Thus, cooperation among the involved jurisdiction is paramount as illustrated through Justice Brozman’s own words:

“The joint administrators in England and the examiner in New York, subject to the jurisdiction of both courts, have carried out the administration of MCC in unprecedented cooperation with each other… in accordance with a document called the Protocol”.[7]

A similar scenario is observed in the landmark judgement of the NCLAT in Jet Airways (India) v. State Bank of India, where along with the domestic insolvency proceedings of Jet Airways in India, the Dutch Administration sought to initiate parallel proceedings in Dutch Courts. Similar to the US and UK dispute in MCC, there was no pre-existing legislation in India that laid down effective procedures to overcome cross-border disputes. Initially, the country adopted a territorial approach completely ignoring the Dutch proceeding declaring it to be a nullity in law. However, in an appeal at NCLAT, the Tribunal permitted the first cross-border insolvency proceeding with the main insolvency proceeding occurring in India and governed by the domestic laws after securing the cooperation between the Dutch Bankruptcy Administrators. The cooperation between the jurisdictions were once again obtained through an agreed protocol founded on the model of “pure universalism”.

While Section 234 and 235 of the IBC recognised the creation of bilateral agreement which may be used as the basis for such a ‘Protocol’ the Ministry of Finance identified that such an ad-hoc procedure would significantly delay the insolvency proceedings.[8]. Thus, there is a need for one such ‘Protocol’ to be in place for every jurisdiction or how they would address cross-border issues including conflict of law as well as recognising cooperation among other involved countries and so on. To assist all jurisdictions the United Nations Commission on International Trade Law (“UNCITRAL”) adopted the Model Law on Cross-Border Insolvency (“Model Law”).

Well known nations such as the United Kingdom, United States, Singapore, Australia, South Africa, Korea, Canada and Japan have adopted and incorporated the Model Law into their local insolvency legislations.[9] The Model Law addresses the four core pillars of the Cross Border Insolvency which was identified by the ILC in their Report and subsequently reitereated by the Ministry of Finance:

- Access

- Recognition

- Cooperation

- Coordination.

The ease of its adoption lies in the fact that it:

“…respects the differences among national procedural laws and does not attempt a substantive unification of insolvency law. Rather, it provides a framework for cooperation between jurisdictions, offering solutions that help in several modest but significant ways and facilitate and promote a uniform approach to cross-border insolvency”.[10]

The Model law appears to emulate the feature of true universalism by recognising the differing jurisdictions and their respective procedure for initiating insolvency proceedings but at the same time attempts to bring all cross-border proceedings under a uniform and yet international framework, emulating a territorial approach. Thus, the Model Law adopts as E.S. Adams and J.K. Fincke described the approach of Modified Universalism with a Territorialist Foundation.[11]

Reports and discussions in India

For resolving the concerns relating to cross-border insolvency in India, the adoption of Model law was proposed by the ILC in its two-part report.[12] In its 2nd part of the Report, the ILC formulated the Draft Part Z which is heavily inspired by the Model Law and imbibes within itself, the key highlights of the same.[13] The ILC justified its adoption for the following reasons as provided in its Report:

- The existing provisions with respect to cross-border insolvency contained in section 234 and 235 of the IBC does not provide a broad or an exhaustive framework for cross-border insolvency matters.

- The enforcement mechanism of foreign judgements under Civil Procedure Code is not wide enough to incorporate all the insolvency orders.

- Adoption of Model law will help in increasing foreign investments as it provides avenues for recognition of foreign insolvency proceedings which in turn will strengthen coordination between domestic and foreign insolvency proceedings.

- The Model law provides flexibility to protect the public interest and it also gives priorities to the domestic proceedings.

Succeeding the ILC Report, the MCA constituted the Cross Border Insolvency Rules/ Regulations Committee (“CBIRC”) through the Office Order dated 23rd January 2020, to ensure smooth implementation of the cross-border insolvency provisions proposed by the ILC Reports. The CBIRC was to make recommendations on the rules and regulations required to operationalise the ILC Report.

Subsequently, through the Office Order dated 21st February 2020, the MCA also included the following responsibilities into the mandate of the CBIRC: –

- study of the UNCITRAL Model Law for Enterprise Group Insolvency

- recommendations on cross-border resolution and insolvency of enterprises

As on the date of this article, the 1st Report of the CBIRC has been issued on 23rd November 2021.[14]

The Ministry of Finance, in its Economic Survey of 2021-22 had further identified the need for a definite insolvency framework for cross-border scenarios which would address the following: –[15]

- The degree of access which an insolvency administrator may exercise over assets held in a foreign jurisdiction.

- Whether the country should follow the principle of secondary insolvency i.e., domestic creditors receive a higher priority over their foreign counterparts.

- Recognition of the claims made by local creditors in a foreign jurisdiction.

- Recognition and enforcement of local securities, taxation system over local assets where a foreign administrator is appointed.

Key highlights of the Draft Part Z:

The ILC after analysing the provisions of the UNCITRAL Model law, recommended the inclusion of the Draft Part Z. Key highlights of the Draft Part Z are as follows:

- Limited applicability: Currently the applicability of the Draft Part Z is limited only to the Corporate Debtors (“CD”) including foreign companies under the Companies Act 2013 (“CA”) and does not apply to the insolvency of individuals and foreign partnership firms. The rationale behind the limited applicability is that the full-fledged implementation initially could be difficult to tackle due to lack of on-field knowledge of the practical hindrances that could come in the way.

- Legislative reciprocity: The Draft Part Z provides for legislative reciprocity i.e., recognition and enforcement of foreign court’s judgement in the domestic court if the foreign court has also adopted similar legislation. Therefore it would apply to those foreign States that have adopted the UNCITRAL Model Law and the foreign States with which the Central Government has entered into an agreement for enforcing provisions of the Code.

- Rights of the foreign creditors: The foreign creditors shall have rights regarding the commencement of, and participation in, a proceeding at par with the domestic creditors subject to the ranking of claims in a proceeding under the Code. Also, whenever a notice is required to be given to a creditor in India, similar notice shall also be given to the foreign creditors.

- Centre of Main Interests (“COMI”): If the registered office of the CD is not moved to any other country in the preceding 3 months then the COMI is the registered office of the CD. Also, while determining COMI of the CD, the Adjudicating Authority may conduct assessment as and when required.

- Avoidance to actions detrimental to creditors: The foreign representative shall be entitled to make an application to the Adjudicating Authority (“AA”) for an order relating to sections 43, 45, 49, 50 and 66 of the IBC upon recognition of the foreign proceeding. And for the purpose of determination of the insolvency commencement date of the foreign proceedings shall be determined as per the law of the country in which the foreign proceeding is taking place.

- Types of proceedings: Two types of foreign proceedings are described in the Draft Part Z which are-

- Foreign main proceedings: takes place in the jurisdiction where the CD has its COMI.

- Foreign non-main proceedings: takes place in jurisdiction(s) where the CD has an establishment, other than where the COMI is located.

- Commencement of a proceeding after recognition of a foreign main proceeding: After recognition of foreign main proceedings, it can be initiated under this Code only if the corporate debtor has assets in India and the effects of the proceedings shall be restricted to the assets located in India and to the extent it is necessary for implementation of cooperation and coordination to other assets that, under the laws of India, should be administered in that proceeding.

- Coordination between more than one foreign proceedings: Coordination is an integral element and to that effect the ILC report provided the following:

- Relief granted to the representative in the foreign non main proceedings after recognition of foreign main proceedings shall be consistent with the foreign main proceedings.

- Relief granted under foreign non main proceedings shall be reviewed and modified if it is inconsistent with the review granted to the foreign representative in the foreign main proceedings.

- The Adjudicating Authority shall modify, terminate or grant relief for the purpose of facilitating coordination between two or more non main proceedings that has been recognised.

- Appeals and the Appellate Authorities: Every appeal against the order of the Adjudicating Authority shall be made to the National Company Law Appellate Tribunal (NCLAT) within 30 days. Provided that the NCLAT may allow the filing of appeal beyond the said period of 30 days if it is satisfied that there was sufficient cause for not filing the appeal, but such period shall not exceed 15 days.

Every appeal against the order of NCLAT involving a question of law shall be made to the Supreme Court within a period of 45 days from the date of receipt of such order. Provided that the Supreme Court may allow the appeal beyond the said period of 45 days if it is satisfied that there was sufficient cause for not filing the appeal, but such period shall not exceed 15 days.

The Draft Regulations: A Sequential Guide to Cross-Border insolvency in India

For ease of understanding, we would chart out the sequential procedure as to how cross-border insolvency would be dealt with under the Draft Part Z, while at the same time summarizing and pointing out relevant issues with respect to its implementation after considering all reports (ILC and CBIRC) issued so far in India.

Pre-Initiation

Who is excluded?

The ILC had excluded certain systemically important Non-Banking Financial Companies (NBFCs) which had been notified by the Central Government. As such the procedure for such notification has been encoded in Clause 29. The insolvency of these entities, in line with the applicability notification dated 18th November, 2019,[16] would be governed under the Insolvency and Bankruptcy (Insolvency and Liquidation Proceedings of Financial Service Providers and Application to Adjudicating Authority) Rules, 2019 (“FSP Insolvency Rules”). In addition to the exclusion of critical financial (banks, insurance) companies, the CBIRC has also recommended the exclusion of utility and infrastructure services (Electricity, water, railways) and such other entities or classes which would be notified by IBBI.

The Corporate Debtor

Now, the Draft Part Z recognises that cross border insolvency proceedings can only be initiated against corporate debtors. As far as the IBC is concerned, s.3(7) read with s.3(8), provides that the ambit of ‘Corporate Debtors’ are restricted to: –

- Companies incorporated under the Companies Act 2013 (“CA”) or the Companies Act 1956.[17]

- Limited liability partnerships under the Limited Liability Partnerships Act 2008[18]

- Any other person incorporated with limited liability excluding Financial Service Providers (“FSP”)[19]

The ILC stated that only for the purposes of Part Z, a corporate debtor would include foreign companies. It must be noted the Code does not define a ‘foreign company’ but allows incorporating definitions from other laws including the CA. Thus, an entity which is, say, incorporated in the United States and having a place of business in India would be subjected to the Draft Part Z if it undergoes insolvency.

However, the issue here as identified by the CBIRC is twofold:

The winding up of “unregistered companies” under the CA

If a situation arises where a foreign company having a place of business in India is unable to pay off its debts to domestic creditors, the latter may initiate winding up of the said unregistered business following an entirely different procedure provided under s.375 of the CA. This would result in duality of procedure in cases where the corporate debtor is unable to pay off its debts to domestic creditors and does not voluntarily undergo insolvency.[20]

The ministry of corporate affairs is yet to notify whether foreign companies would be considered as unregistered companies. As of now the only solution would be registering and incorporating a separate corporate entity in India to escape s.375 of the CA. While the subsidiary would constitute as a separate legal entity, the shares that foreign parent company own would be subject to cross-border insolvency as per precedent in the case of Vodafone v. Union of India.[21]

As per s.2(42) of the CA, for a company to be considered as foreign company under IBC, it should have some form of business in India. Such a conception fails to recognise a business setup such that a company with no presence in India may have unpaid domestic creditors. These domestic creditors cannot benefit from the Draft Part Z as the said companies are not considered ‘foreign companies’ since they have no business in India.

To rectify these issues, the CBIRC has recommended to separately define ‘foreign companies’ under the IBC such that the Draft Part Z would also be applicable to entities that are incorporated with limited liability under the laws of a foreign country as originally envisioned in the proviso to Clause 1(2), escaping the control of s.375 of the CA.

Now that we’re aware of the parties who can participate in cross border insolvencies under the Draft Part Z, the ILC has envisioned that notified NCLT benches can hear cross-border insolvency cases. The CBIRC recommended that there should not be any discrimination as to which benches should be eligible to hear such cases as it would result in inefficiencies since members are transferred from one bench to another and if a the specific bench is engaged in a local IBC case, the same would have to be shifted to another bench outside the territory of the corporate debtor’s office to accommodate the cross border case – disrupting NCLT’s territorial jurisdiction. Thus, in finality the designation of NCLT benches would depend on the location of the corporate debtors’ office (will be discussed later) and in case of foreign companies, notified NCLT benches.

Submission of Applications

Granting foreign representatives access to domestic courts

While evaluating 15 jurisdictions that have adopted the Model Law, the CBIRC could not discern any form of rule-based qualifications for the right of foreign representatives to access local courts. As far as India is concerned, there is no legislation that specifically disallows foreign representatives to access the NCLT. In fact, as illustrated through the MCC and Jet Airways cases, the need for foreign access is paramount if not foundational to cross-border CIRP. For instance, it is not reasonable for a judge at NCLT to be familiar with the CIRP counterpart in South Africa and would often require such foreign representatives (legal counsel) for their aid.[22]

Regulation

Generally governing foreign representatives through a code of conduct falls within the responsibility of the designated court or tribunal and not the national regulatory authority. The same is reflected in countries such as the United Kingdom and the United States. However, the CBIRC while noting this observation recommended that the regulatory authority i.e., the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Board of India (“IBBI”) would bear the responsibility.

The need for regulating such entities is born from the conservative approach of the ILC taking into consideration the position of the country, to which the CBIRC had given due weightage. To that effect, foreign representatives would be given access to the insolvency system and infrastructure in India, including appearing before the NCLT for the purposes of cross-border insolvency but would be regulated.

The said regulation would be mandated by the Central Government in coordination with the IBBI. The Report of the CBIRC sheds light on the nature of such a regulation to be a ‘principle-based light-touch code of conduct’. The CBIRC specifically pointed out to Schedule 1 of the IP Regulations 2016, mainly to its provisions of: –

- Integrity and objectivity

- Independence and impartiality

- Representation of correct facts and correction misapprehensions

- Information management

- Confidentiality

Apart from a code of conduct, the CBIRC proposed the creation of an online mechanism maintained and governed by the IBBI. The said mechanism would allow foreign representatives to submit an application for authorisation which must be done at the time of applying for authorisation or cooperation to the NCLT under Part Z or immediately thereafter.

The IBBI can reject such applications of foreign representatives in two cases:

- Misconduct in a previous proceedings conducted by the IBBI

- Existence of a pending disciplinary proceeding before the IBBI.

The need for the IBBI’s authorisation is not to be considered as a prerequisite to NCLT proceedings and if such applications are rejected, the IBBI notifies the relevant NCLT bench and fresh applications for a different foreign representative(s) can be filed with the NCLT proceedings occurring in parallel. To ensure smooth operations, the IBBI is time bound to reject applications within 10 days failing which such representatives would automatically be authorised.

Granting domestic representatives access to foreign courts

As aforementioned, generally, there are no restrictions that foreign countries place for recognising representatives outside their local jurisdiction and as far as the IBC and the IP Regulations 2016 are concerned, there are no constraints on Indian Insolvency Professionals (“IPs”) from applying for recognition in foreign jurisdictions.

In pursuant to the same, as per the CBIRC’s recommendation, such IPs seeking access to a foreign insolvency system and infrastructure, are to be bound to report such assignments to IBBI. Moreover, the IBBI is to formulate the format of such a report to be submitted.

Application for Cooperation between Courts, Foreign Representatives, IPs and CDs

After the COMI has been determined, regardless of whether the domestic proceedings is the main or non-main, the NCLT bench having the territorial jurisdiction would be the designated bench.[23] Now, in cases where a foreign proceeding is underway there might be a need for foreign representatives to seek the cooperation of the AA, CDs or IPs in India even if the AA has not recognised the foreign proceeding. Clause 22 envisions the spirit of cooperation and if the CBIRC report is to be considered, a foreign representative can apply for the Tribunal’s cooperation regardless of whether an application for recognition of the foreign proceedings has been made before the tribunal.[24] However, such cooperation does not authorise the NCLT to issue any form of reliefs or impose any form of burden on the involved parties. The purpose is to merely assist.

Application for Recognition of a Foreign Proceeding

Clause 12(2) expressly lays down what an application for recognising a foreign proceeding should contain. This recognition authorises the AA to issue reliefs and adjudicate upon the issue, a feature previously unavailable in an application for cooperation. Additionally, as per the CBIRC Report, the foreign representative is to file an affidavit in support of their application along with the submission of any documents or evidence which would, in the opinion of the foreign representative(s) assist the AA. To that effect, the Central Government may release a prescribed format for digital submission of such applications which would require the full disclosure of the CD’s business, its creditors, status of the foreign proceedings, whether the foreign jurisdiction has adopted the Model Law along with a statement affirming that the foreign representative(s) are duly authorised to make the application and so on.[25]

Main Proceedings

Notices

Once an application has been formally submitted before the Tribunal, there is a need to notify all creditors regardless of whether they have an address in India or not.[26] While the Model Law does have a prescribed format for such notices, the ILC has decided on a format under clause 11(3), the manner of circulation is to be decided by the IBBI. To that effect, one could refer to its domestic counterpart under the CIRP Regulations for the manner in which a notice is to be circulated. Additionally, the CBIRC recommended the use of the IBBI (Application to Adjudicating Authority) Rules, 2016 which is the standard for domestic IBC cases. In cases where the same is not possible, the notice can be issued on the CD’s website or on a website designated by the IBBI.

Cooperation between AA & Foreign Courts

After the application for initiating cross border insolvency is permitted and recognised in both jurisdictions, there is a need to ensure that there is adequate communication and cooperation among the involved jurisdictions and relevant parties, as illustrated through the MCC and the Jet Airways case.

Thus, to ensure the same, the ILC in its 2nd Report of March 2018, recommended the need for a proper framework to facilitate communication and cooperation through clauses 21, 22 and 23 of the Draft Part Z. It was suggested that the framework is to be notified by the Central Government in consultation with the Adjudicating Authority in the interest of all stakeholders. . The CBIRC in its own report specifically recommended the adoption of the several existing Guidelines for Communication and Cooperation between Courts in Cross-Border Insolvency Matters.

The CBIRC While agreeing with the recommendations of the ILC, made note of the guidelines framed by the Judicial Insolvency Network 2019 (“JIN”) among others, more specifically, the provision of a ‘Facilitator’. Perusing the JIN Guidelines, the Facilitator is to be a single individual, one appointed by each jurisdiction. And while the spirit of cooperation is commendable So here is prepared to cross border cases involving 2 jurisdictions only. Both the JIN Guidelines as well as the Draft Part Z does not comprehend the existence of a cross-border dispute that involves more than two jurisdictions. Granted that the current Draft Part Z spoke of creation of a specific Council, this set concert is to act at the direction of the adjudicating authority And if iIn such cases, there were to be multiple facilitators To be appointed, they would need to coordinate amongst themselves before relaying information to the judges of the designated Courts and/or Tribunals. This is an unaddressed issue.

COMI

One of the first elements to determine the COMI would be the date when the insolvency was sought: whether it would be the date when the application for a foreign insolvency was initiated or the date when it is brought forth through an application, before the NCLT. The ILC decided to leave it open to interpretation as the Model Law remains silent on the issue. The consequence, as correctly identified by the CBIRC, would be issuance of contradictory judgements, consuming more time and money with no discernible benefit. The CBIRC was in favour of considering the date of commencement of the foreign proceeding as the effective date for the purposes of COMI. The same would also warrant alteration in clause 14 of the Draft Part Z.

The CBIRC was critical of the ILC’s approach in Clause 14 where it considered the central place of administrator superior to certain ‘other factors’ to determine the COMI. These ‘other factors’ are more than often considered at par with the central place of administration in practice.[27] Moreover, these ‘other factors’ play a crucial role in determining the central place of administration. For instance, the place where the senior management of the debtor is situated or where management decisions are taken all contribute to the determination of the Central Place of Administration.[28] Additionally, the CBIRC have added to the list of these ‘other factors’ which are to be recognised by the Draft Part Z.

Reliefs

- Discretionary: Provisions for discretionary reliefs are encoded in clause 18 with the CBIRC further recommending that in exercise of clause 18(1), the AA may allow the foreign representative access to books of accounts, audit reports, records and other forms of documents of the CD.

- Interim: There were no provisions for interim reliefs in the IBC when the ILC Report was published. However, while the CBIRC Report was being drafted, the ILC in 2020 recommended the addition of interim reliefs to domestic proceedings and to that effect, the same standard would be incorporated in Part Z.

Comparative Analysis

Majority of stakeholders have already agreed that the Draft Part Z which adopts provisions from the Model Law is a step in the right direction. However, a proper framework is far from complete as a much greater level of deliberations is required before the final draft can be prepared. Currently, we are yet to see the completion of the second part of the CBIRC Report. However, based on information and notifications already available we can identify the trajectory of certain key provisions of the Draft Part Z when compared with the Model law as illustrated through the summarising table below:

| UNCITRAL MODEL LAW | ILC REPORT 2018 | CBIRC REPORT 2020 |

| Excluded entities | ||

| Article 1(2): This Law allows the enacting countries to exclude certain entities from the ambit of Model law. Generally, banks and insurance companies are excluded because the insolvency of these entities affects the interests of large numbers of individuals. | The committee in its Report recommended that the Central Government be empowered to notify the entities that may be excluded from the scope of the Draft Part Z. | The committee recommended the exclusion of FSPs from Part Z along with companies engaged with critical finance, utility and infrastructure services. It also recommended defining ‘foreign companies’ under Part Z and sought clarification whether ‘foreign companies’ are ‘unregistered companies’ under the CA. |

| Notice to foreign creditors | ||

| Article 14: This Law provides for giving individual notices to the foreign creditors wherever a notice is required to be given to the creditors of the insolvent debtor. | It provides that wherever a notice is required to be given to the domestic creditors of the debtor, similar notice shall also be given to the foreign creditors. | Notice can also be communicated through the CD’s website or as designated by the IBBI. |

| Reciprocity | ||

| The Law does not provide a complete rejection of reciprocity and left its application to the discretion of the enacting States. | As per the recommendation of the committee, the Model Law may be adopted initially on a reciprocity basis. This may be diluted subsequently upon re-examination. | [no new additions] |

| Provisions w.r.t. other interested persons | ||

| This Law allows creditors as well as “other interested persons” in foreign countries to initiate and participate in the proceedings. | The committee recommended the right to initiate and participate in the proceedings be restricted to the creditors. | Allowed foregin representatives to seek cooperation or apply for recognition of foreign proceedings before the AA following a specific procedure. |

| Adjudicating Authority | ||

| This Law provides that a court shall be authorised by the enacting country to exercise the powers granted under the Model Law. | The Committee recommended that benches of the NCLT may be notified by the Central Government in this regard. | All benches of NCLT should be equally eligible based on their territorial jurisdiction. For foreign proceedings, notified NCLT benches may be chosen. |

| Interim relief | ||

| This Law provides for granting of interim relief by the court until the application for recognition of foreign proceedings is decided. | The committee recommended that the provisions w.r.t. interim relief may not be provided in Draft Part Z as the same is not provided in the IBC, 2016 either. | The ILC subsequently recommended the inclusion of interim reliefs for domestic proceedings. To that effect, the same standard would be maintained for cross-border insolvencies as well. |

Concluding Remarks

While crystalizing the legal framework for cross border insolvency in India, it is crucial that the Indian Framework in also in sync with the extant laws in the partner countries, which are covered under the scope of the Draft Regulations. Hence, the proposed framework, which is heavily inspired from the Model Laws, already adopted by 44 countries, would be a favourable approach since with would provide added synergic benefits and less differences, which are crucial to ensure success of such a Cross Border regime.

For other resources on Cross Border Insolvency, please see-

- Comments of the 1st Part of the ILC ReportPresentation on IBC Updates along with Cross-Border Insolvency as on 2020

[1] https://www.indiabudget.gov.in/economicsurvey/

[2] Economic Survey, Chapter 04 – Monetary Management and Financial Intermediation – Para 4.66 to 4.68

[3] https://www.indiabudget.gov.in/doc/Budget_Speech.pdf

[4] Para 76 of the Speech of Hon’ble Finance Minister, Smt. Niramala Sitharaman

[5] Anderson K, ‘The Cross-Border Insolvency Paradigm: A Defense of the Modified Universal Approach Considering the Japanese Experience’ 102 <https://scholarship.law.upenn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1366&context=jil> accessed 21 January 2022

[6] [1992] BCC 757

[7] In Re Maxwell Communication Corp., 170 B.R. 800, 801-02 (Bankr. S.D.N.Y.1994), aff’d, 186 B.R. 807 (S.D.N.Y. 1995). See Jay Lawrence Westbrook, The Lessons of Maxwell Communication, 64 Fordham L. Rev. 2531 (1996). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr/vol64/iss6/3

[8] https://www.indiabudget.gov.in/economicsurvey/doc/echapter.pdf

[9] UNCITRAL, https://uncitral.un.org/sites/uncitral.un.org/files/media-documents/uncitral/en/overview-status-table.pdf

[10] Digest of Case Law on the UNCITRAL Model Law on Cross-Border Insolvency https://uncitral.un.org/sites/uncitral.un.org/files/media-documents/uncitral/en/20-06293_uncitral_mlcbi_digest_e.pdf

[11] Edward S Adams and Jason Finke, ‘Coordinating Cross-Border Bankruptcy: How Territorialism Saves Universalism’ (Social Science Research Network 2009) SSRN Scholarly Paper ID 2624871 <https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=2624871> accessed 21 January 2022

[12] A detailed account of the 1st Part of the ILC Report can be found here

[13] A general account of the provisions of the Draft Part Z along with a discussion on the Model Law can be found here

[14] https://ibbi.gov.in/uploads/resources/47fe7576712190d5554e2e50ce646e2f.pdf

[15] https://www.indiabudget.gov.in/economicsurvey/doc/echapter.pdf

[16] https://ibbi.gov.in//uploads/legalframwork/7bcd2585a9f75b9074febe216de5a3c1.pdf

[17] s.2(20), Companies Act 2013.

[18] s.2 , Limited Liability Partnerships Act 2008.

[19] As per Notification dated 18th November, 2019, insolvency process can be initiated against NBFCs, including HFCs, having net asset size of Rs. 500 crores or more. This initiation, however, shall be as per the FSP Insolvency Rules

[20] S.375(3)(b) CA 2013

[21] (2012) 6 SCC 613

[22] United Nations Commission on International Trade Law 2012.

[23] The CBIRC recommendation is followed otherwise it will be designated benches as notified by the Central Government which does not prescribe where such an application is to be made.

[24] An Approach adopted by the UK and Singapore

[25] Box 15, CBIRC Report 2020, page 69

[26] Draft Part Z, Clause 11(1). See also: IBBI (Application to Adjudicating Authority) Rules, 2016

[27] Stanford International Bank Ltd., Re [2010] EWCA Civ 137; In re Millennium Global Emerging Credit Master Fund Ltd, District Court Southern District of New York, Case No. 11 Civ. 7865 (LBS) (25 June 2012); In Re Videology Ltd, England and Wales High Court of Justice, Chancery Division, Companies Court, Case No: CR-2018-003870 (16 August 2018); [2018] EWHC 2186 (Ch); Zeta Jet Pte Ltd and others (Asia Aviation Holdings Pte Ltd, intervenor), 2019 SGHC 53.

[28]re Millennium Global Emerging Credit Master Fund Ltd, District Court Southern District of New York, Case No. 11 Civ. 7865 (LBS) (25 June 2012)

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!