Stewardship Responsibilities of Institutional Investors in India: Global perspectives and the Way Ahead

– Sikha Bansal, Partner & Neha Malu, Senior Executive | corplaw@vinodkothari.com

“Stewardship” literally means the act of protecting the rights of the person to whom it is acting as a steward. In the context of shareholders’ governance and capital markets, the institutional investors play the stewardship role for their clients/ beneficiaries as the funds invested by the institutional investors in the companies actually belong to the large pool of diversified investors who had invested in the institutional investors and hence it will not be wrong to say that the institutional investors are the “stewards” and not the “owners” of the funds invested by them. As defined by UK Stewardship Code (2020)[1], “Stewardship is the responsible allocation, management and oversight of capital to create long-term value for clients and beneficiaries leading to sustainable benefits for the economy, the environment and society”.

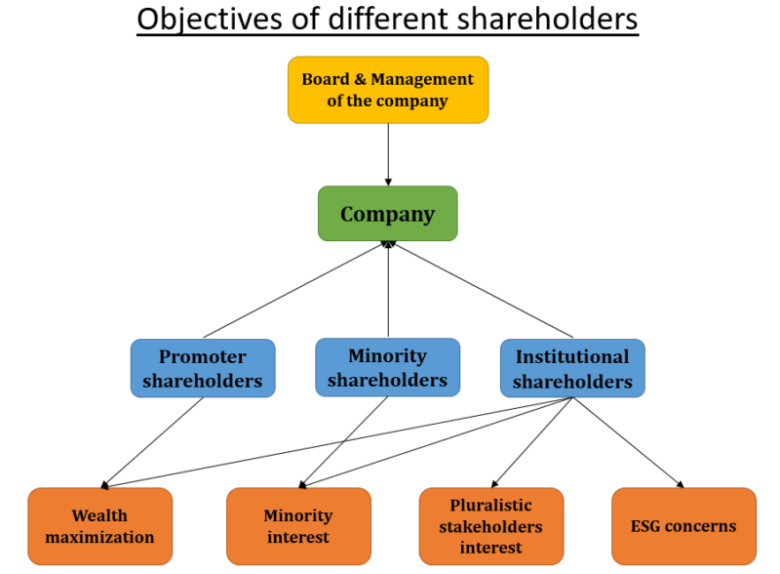

There are diverse interests involved in a corporate structure – while promoters would be driven by the sole objective of wealth maximisation; other stakeholders would include public shareholders, society and environment in general. Although institutional investors work for value maximisation for their clients/beneficiaries; however, to achieve the same, they need to consider all the factors, including strategy, governance aspects, social and environmental considerations, etc. The objective is achieved through engagement with the investee. Given the significant extent of their shareholdings in listed entities, the role of institutional investors (viz., mutual funds, alternative investment funds, public financial institutions, banks, insurance companies, etc.), becomes extremely significant. The institutional investors themselves are repositories of the money of their beneficiaries, that is, the investing public; which puts such investors in the position of stewards.

Stewardship responsibilities of institutional investors came into focused attention , mainly after the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) whereafter the regulators across the globe (starting with the UK in 2010) started codifying their expectations from institutional investors as stewards. The backdrop to this attention was the findings that there were substantial conflicts of interest, lopsided remuneration structures in financial institutions, even as institutional shareholders in such financial institutions played a passive role. India, too, joined the list of countries which codified stewardship principles; while some pieces of regulatory statements were issued in 2010 and 2014 for mutual funds; however, a comprehensive set of stewardship responsibilities was first issued by the insurance regulator (IRDAI), followed by the pension fund regulator (PFRDA) and then the securities regulator (SEBI).

This article elaborately discusses the role and the responsibilities expected from institutional investors as stewards, in view of several sets of codified rules, in India and other jurisdictions and also emphasises the importance that such function carries with it. Further, as the authors deliberate in this article, while the stewardship principles in India are largely similar to globally accepted standards, the authors see a room for improvement in the Indian stewardship codes. Notably, global regulators are also extending stewardship principles to service providers and intermediaries such as proxy advisors, investment advisers, etc. Additionally, global principles also provide for enhanced and qualitative reporting requirements for institutional investors as well as service providers.

Need for the institutional investors to act as ‘Stewards’

The primary reasons for a pressing need for stewardship are two:

One, the increasing proportion of institutional equity in listed companies. As per the OECD Working Paper on ‘Institutional investors and stewardship (2022)’[2], most advanced markets are seeing an increase in the importance of various forms of institutional ownership, replacing direct ownership by individual households. The shift is evidently visible in countries like the UK, US and Japan. Coming to data, OECD Paper suggests that institutional investors now represent a substantial part of equity ownership globally. At the end of 2020, they owned 43% of the global market capitalization of listed companies, equivalent to almost USD 44 trillion. This makes them the single largest investor category, with public equity holdings four times larger than those of both corporations and the public sector. From 2007 to 2019, the equity holdings in listed companies by the 50 largest institutional investors grew from USD 12 trillion to USD 24 trillion in real terms.

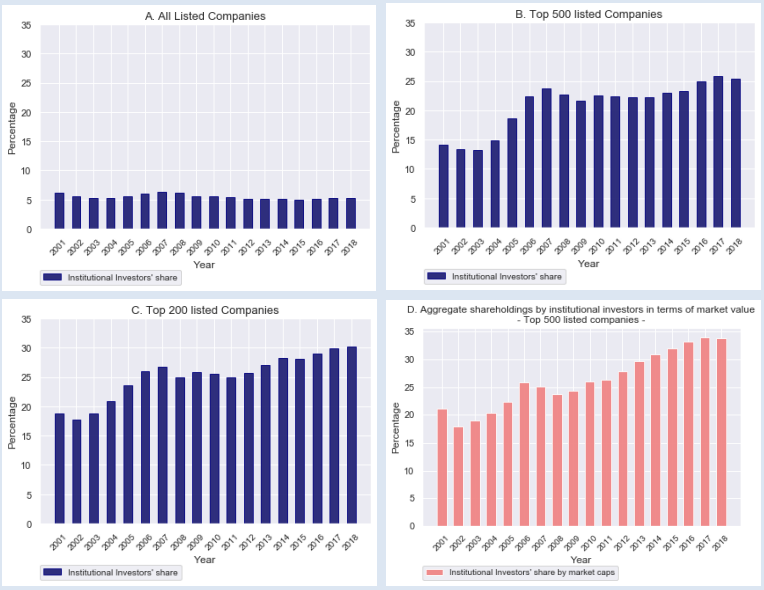

An OECD publication on ‘Ownership Structure of listed companies in India’ (2020) depicts steady growth in the size and influence of institutional investors in Indian capital markets. The aggregate market value of shareholdings by institutional investors increased from 21% of the overall market capitalizations in 2001 to 34% in 2018. Further, as a proportion of total institutional ownership, banks represent the largest share for all listed companies. In the past five years, this has remained above 30% since 2006. In the top 500 listed companies by market capitalisation, mutual funds have increased from 18% in 2013 to 30% in 2018[3]. The graphs below depicts the Institutional ownership in Indian listed companies (2001-2018)[4].

Secondly, companies have become increasingly more powerful in terms of their economic, social and environmental impact. Not only does the working of companies affect their shareholders – there are multiple and far reaching implications including economic (the point best illustrated by the aftermath of the GFC, as well as environmental and social (an array of climate based litigation and activism bears a testimony to that effect)[5]. With ESG considerations and concepts like ‘responsible investing’[6] on the rise, institutional investors cannot afford to lose sight of the same. Thus, the engagement of institutional investors with the investee and the kind of investments decisions these investors take, ought to be well aligned with the ESG goals – at a macro as well as micro levels. As discussed later in this article, the stewardship codes of several jurisdictions have also included ESG aligned investment responsibilities for the institutional stakeholders.

Therefore, it is the ‘weight’ which these institutional investors carry in terms of their position and the voting rights, which requires them to undertake a higher share of shareholder responsibilities; at the same time ensuring that ‘intervention’ is minimal and conditional. When the UK initiated stewardship principles in 2010, this was the basic intent; the Consultation Paper said: “Given the weight of their votes, the way in which institutional shareholders use these rights is of fundamental importance. While shareholders cannot and should not be involved in the management of their company, they can insist on a high standard of corporate governance as a long-term driver of good investment performance.”[7]

The push for stewardship became stronger after the GFC. GFC was mostly concerned with governance of financial entities, and in financial entities, the shareholding of institutional holders was even higher. The Walker Report[8] stated: “…there is a need for better engagement between fund managers acting on behalf of their clients as beneficial owners, and the boards of investee companies. Experience in the recent crisis phase has forcefully illustrated that while shareholders enjoy limited liability in respect of their investee companies, in the case of major banks the taxpayer has been obliged to assume effectively unlimited liability. This further underlines the importance of discharge of the responsibility of shareholders as owners, which has been inadequately acknowledged in the past… there should be clear disclosure of the fund manager’s business model, so that the beneficial shareholder is able to make an informed choice when placing a fund management mandate”[9].

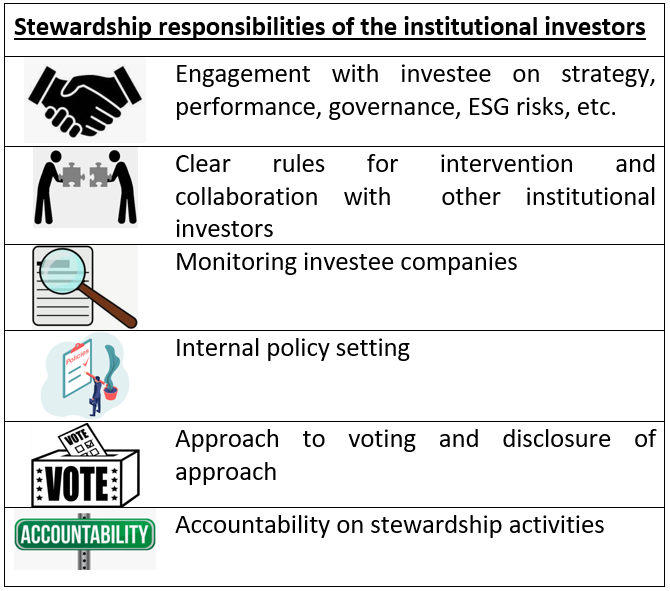

Stewardship responsibilities of the institutional investors

The G20/OECD Principles of Corporate Governance[10] state that the institutional investors should develop and disclose their policies on how they exercise ownership functions in their investee companies (Principle III.A) and on how they manage material conflicts of interest (Principle III.C). The UK Stewardship Code (and respective codes of various other jurisdictions) lists out an extensive set of stewardship responsibilities. Besides, International Corporate Governance Network (ICGN) has also framed ‘Global Stewardship Principles’[11]. The principles, however, remain broadly similar, and can be briefly encapsulated as follows –

- Formulation of policies for discharge of stewardship duties and public disclosure: The policy outlines the manner in which responsible investment practices would be imbibed in the functioning of the investor, and the manner in which stewardship responsibilities would be fulfilled, including wherever the responsibilities are outsourced. Integral to implementation of such policy is sensitisation and training of all relevant stakeholders. Besides, public disclosure is needed as the institutional investors have scattered beneficiaries.

- Active engagement with the investee companies: Engagement may be at various fronts, including strategy, corporate governance (including compensation, related party, key managerial and executive appointments, etc.), material risks faced by the investee, etc.

- Priority to the underlying investors in case of conflict of interest: Generally the institutional investors hold majority stake in the share capital of investees which may lead to the events where conflict of interest may arise. In such scenarios, being the steward to the underlying investors, the institutional investors are under the obligation to ensure giving the first preference to the investors for whom it acts as the steward. Policy guidance should be available on how situations of such conflict would be handled.

- Have clear rules for intervention – Engagement should not be so excessive as to lead to intervention in all and sundry cases. Circumstances must be identified which necessitate active intervention. Need for intervention should be assessed in light of possible outcomes. Interventions may be either at their own level or through collaborations – in any case, clear rules should be established through policies.

- Approach to voting and disclosures: The institutional investors ought to take their own decisions on resolutions/proposals of investees, rather than blindly following management decisions and/or advisory of proxy advisors. Clear rule setting in this regard, is therefore important. Policy shall ideally set out guidelines to take a decision on whether to vote or abstain, and if vote, then whether in favour or against.

- Responsible decision making: Because of large holding in the investee company, the institutional investors have the potential to influence the decision making and ultimate course of action of the investee company. Further, the decisions taken by the institutional investors in exercise of the voting rights bestowed on it, may directly impact all the stakeholders of the investee company. Therefore, it is one of the prime duties of the institutional investors to make informed decisions. Additionally, even if the proxy advisors/other agents are engaged by the institutional investors for assisting it in discharge of its voting obligation, the institutional investors are expected to exercise its diligence and take the informed decisions.

- Monitoring the investee companies: Monitoring is required on all important aspects. Such monitoring can only be effective through continuous engagement (as above). Extent and mechanism of monitoring may depend upon the type of the investee and shareholding proportions of the institutional investor. Exceptions in which monitoring may not be needed may be specified by way of policy.

In practice, different jurisdictions may follow different approaches[12]. For instance, say voting in many countries is at the discretion of the institutional investor on a case to case basis; however, in India, it is mandatory in certain circumstances (see below).

History of Stewardship Codes

In 1991, the Institutional Shareholders’ Committee published a statement on “The Responsibilities of Institutional Shareholders in the UK”[13], which later evolved as ‘The Code on the Responsibilities of Institutional Investors’ (2009)[14] (‘ISC Code’). This statement of principles provided the practices for the institutional investors with respect to discharge of their duties towards the investors whose money was invested in the portfolio investee. The principles stated did not intend to create an obligation on the institutional investors to micro manage the affairs of the investee company but to ensure that the investors whose money was being invested derive value from such investments. Further, the same was for discharge of responsibilities of institutional investors towards the investors whose money was deployed and not for the public at large.

In March 2000, Paul Myners was asked to carry out a review of institutional investment by the Chancellor of the Exchequer so as to identify if there existed any distortion in the decision making of the institutional investors (pension funds). His Report was published in 2001 and set out principles for investment decision making for pension fund trustees (“the Myners Principles”)[15], including a recommendation on incorporating shareholder activism into fund management mandates.

However, it was after GFC that, in UK, a need for review of corporate governance in the banks was felt, and the Walker Report[16] advocated the need of a separate stewardship code – separate from the Corporate Governance Report, “to cover the development and encouragement of adherence to principles of best practice in stewardship by institutional investors and fund managers” (see, recommendation 16) and recommended that the ISC Code should be ratified by the Financial Reporting Council (FRC) and adopted as the Stewardship Code. Thereafter, in July 2010[17], FRC released “The UK Stewardship Code” the primary aim of which was to intensify and strengthen the quality of engagement between the institutional investors and the portfolio investee companies in order to maximize the returns to the investors whose money is deployed and efficient exercise of governance responsibilities by the institutional investors. Later in September 2012[18], the next edition of “The UK Stewardship Code was published” which upgraded the first Code without changing the spirit with which the first Code was published. The UK Stewardship Code has been recently upgraded in 2020 (see below).

Stewardship Codes in some of the major countries across the world

United Kingdom

Since the publication of the initial editions of “The UK Stewardship Code” there has been tremendous change that has occurred in the investment markets. Additionally, the investors have become more conscious and awakened of the environmental, social and governance issues which are now considered to be one of the most important factors in the investment related decisions. Therefore, to account for the changes, the current version of “The UK Stewardship Code” was published in the year 2020[19]. The UK follows the apply and explain approach with this code.

United States[20]

The Investor Stewardship Group that includes some of the largest U.S. based institutional investors and global asset managers developed the ‘Stewardship Framework for Institutional Investors’ which are drawn on similar lines as in case of any other stewardship code across the world as because the prime intent behind drawing these codes is to safeguard the interest of the portfolio investee who have invested in the institutional investors.

European Union

The European Union issued Directive 2007/36/EC on the exercise of certain rights of shareholders in listed companies which was later amended vide Directive (EU) 2017/828[21] (‘Shareholders Rights Directive’/’SRD’). The SRD calls for comprehensive disclosure requirements for both institutional investors as well as asset managers. Besides, it also acknowledges the role of proxy advisors in the voting behaviour of institutional investors. As such, it necessitates transparency requirements on the part of such proxy advisors, in terms of key information relating to the preparation of their research, advice and voting recommendations and any actual or potential conflicts of interests or business relationships that may influence the preparation of the research, advice and voting recommendations.

Australia[22]

To promote good stewardship practices, the ‘Australian Asset Owner Stewardship Code’ was developed in May 2018 for the Australian Asset Owners which broadly includes superannuation funds, endowments and sovereign wealth funds. Similar to the stewardship codes of other countries, this Code also provides principles and guidance to aid the implementation and transparency of the stewardship practices of asset owners in fulfilling their fiduciary duties to their beneficiaries. This Code is voluntary and is made applicable on an “if not, why not” basis pursuant to which all the signatories of the Code are required to publish a Stewardship Statement on their website describing how they apply each of the principles in the Code and if one or more principles have not been applied, the reason for the same. Further, this Code provides a flexibility to the signatories to apply the stated principles that is consistent with the spirit of the principles instead of rigidly reporting against the guidance provided.

Singapore[23]

To keep the stewardship principles relevant and to account for the evolving developments in expectations, market practices and regulations, the updated version i.e., ‘The Singapore Stewardship Principles: For responsible investors 2.0’ was released in March 2022. The major changes incorporated in the principles include integration of ESG considerations into investment decision-making and stewardship practices, application of stewardship to asset classes beyond listed equities, identification of internal structures and governance of institutional investors guiding their stewardship activities and including an outcomes-oriented approach in applying the Principles.

Besides the above, UK-inspired stewardship principles have been exported to other countries as well, including, Brazil, Canada, Denmark, Japan, etc.

Development of Stewardship Code(s) in India

In India, recognition of the stewardship role of institutional investors has been there, although in the formative years, it was not so explicit. For instance, in Life Insurance Corporation of India v. Escorts Ltd.[24], which is seen as one of the earliest examples of shareholder activism by institutional investors, the SC recognised the right of financial institutions as ‘shareholders’ in a corporate entity. It states, “When the State or an instrumentality of the State ventures into the corporate world and purchases shares of a company, it assumes to itself the ordinary role of a shareholder and dons the robes of a shareholder, with all the rights available to such a shareholder. Therefore, the State as a shareholder should not be expected to state its reasons when it seeks to change the management by a resolution of the company, like any other shareholder.”

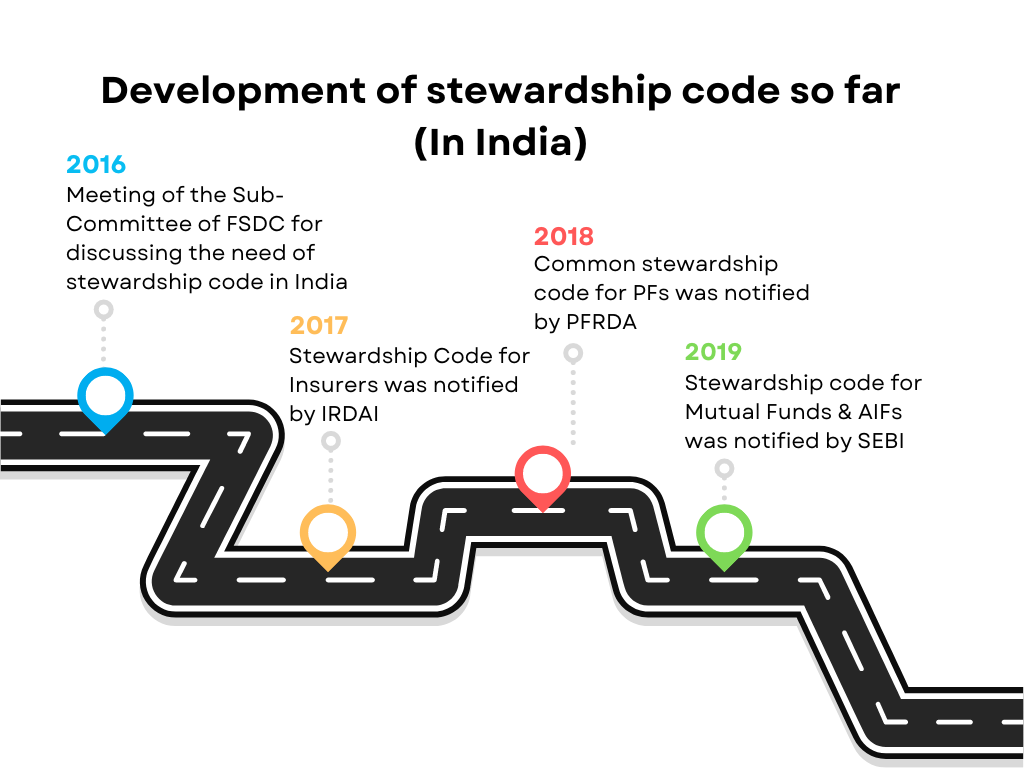

Further, India, as is known, has a fragmented regulatory landscape. As such, there is no single set of guidelines or authority on stewardship. Institutional investors would thus be governed by their respective regulators. Hence, each of the three regulators, namely, IRDAI, PFRDA and SEBI have issued stewardship codes; although, the objectives and design of these codes remain the same.

The expedition for development of a formal stewardship code in India begin in the year 2016 when the Sub-Committee of the Financial Stability and Development Council in its 17th meeting held on 26th April, 2016[25] felt the need for development of stewardship code in India looking at the responsible position an institutional investor holds in the capital market and its fiduciary obligations towards its clients.

The first time a formal code governing stewardship in India was notified by IRDAI in 2017[26] (later, revised in 2020[27]). Following the same, PFRDA issued the “Common Stewardship Code”[28] for pension funds in 2018. Similarly, in case of mutual funds, asset management companies, alternative investment fund, SEBI issued the stewardship code in 2019[29].

Notably, before 2019, SEBI had issued the principles on voting by mutual funds vide Circular dated 15th March, 2010[30] and Circular dated 24th March, 2014[31] which provided for mandatory disclosure of voting policies and actual voting by the mutual fund on different resolutions of the investee company. Both of these circulars were updated in 2021[32], as to mandate mutual funds to vote on certain matters. Interestingly, both SEBI and IRDAI call for participation and voting on resolutions/proposals of investee companies mandatorily in certain specified circumstances – while IRDAI’s mandate is based on the insurer’s AUM and shareholding[33] in the investee; SEBI’s mandate is related to the nature of resolutions/proposals[34]. On the other hand, PFRDA has issued detailed general guidelines[35] on voting, allowing pension funds to take a decision on a case-to-case basis placing focus on the impact of the vote on shareholder value and interests of holders of pension schemes.

The codes are mandatory in nature. Besides, all these Indian stewardship codes provide for a common set of principles, aligned with the various stewardship responsibilities discussed above. The codes also take care of ESG responsibilities, where areas of monitoring investee include ESG risks and factors where intervention of investor may be warranted included ESG risks as well.

What more can India do?

India is, to a great extent, well aligned with the global approach to stewardship responsibilities of institutional investors; including those relating to ESG considerations. There are differences too, for example, while a majority of the world has adopted a soft-law based approach, India has opted for a mandatory hard-law based approach, which had been advocated by experts and academicians[36] owing to fundamental differences in the corporate framework in the UK and in India.

However, there may be things to learn. For instance, the revised UK Stewardship Code of 2020 also envisages certain principles for service providers like investment consultants, proxy advisors, data and research providers that support asset owners and asset managers to exercise their stewardship responsibilities, e.g. the service provider, interalia, should explain and disclose –

- what actions they have taken to ensure their strategy and culture enable them to promote effective stewardship,

- how effective their chosen governance structures and processes have been in supporting their clients stewardship,

- how they have identified and managed any instances in which conflicts have arisen as a result of client interests (where such conflict of interest may arise from ownership structure, business relationships, cross-directorships, client interests diverging from each other),

- how they have reviewed their policies and activities to ensure they support clients’ effective stewardship;

- how they have ensured their stewardship reporting is fair, balanced and understandable, etc.

While SEBI, through its regulations for proxy advisors, investment managers and other capital market intermediaries, lays down a certain set of “code of conduct”, including those relating to conflict of interests; there is no explicit expectation from the intermediaries to – (i) perform specified stewardship responsibilities, and (ii) to facilitate the stewardship responsibilities of their clients.

Further, the UK has laid down elaborate reporting expectations from the institutional investors, including how effective their chosen governance structures and processes have been in supporting stewardship, and how appropriately resourced their stewardship activities are, etc.

In any case, it is the implementation which matters. Studies[37] suggest that the policies and conduct at the institutional entity level, both need further alignment with the intent of stewardship code, and that there is still a room for improvement to achieve the desired objectives of stewardship.

[1] https://www.frc.org.uk/getattachment/5aae591d-d9d3-4cf4-814a-d14e156a1d87/Stewardship-Code_Dec-19-Final-Corrected.pdf

[2]https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/1ce75d38-en.pdf?expires=1672313202&id=id&accname=guest&checksum=DC828CFB80F234AD2CBDABEC1B61DA21

[3] See pages 7, 19-20.

[4] https://www.oecd.org/corporate/ownership-structure-listed-companies-india.pdf

[5] https://vinodkothari.com/2022/09/climate-change-litigation-vis-a-vis-directors-liability/

[6] The Cambridge Institute for Sustainability Leadership defines – “Responsible investment as an approach to investment that explicitly acknowledges the relevance to the investor of environmental, social and governance factors, and of the long-term health and stability of the market as a whole.”

[7] https://www.frc.org.uk/getattachment/58c79137-d436-4882-9eda-f4e23fa939fe/-;.aspx

[8] On 9 February 2009 the Chancellor of the Exchequer, the Secretary of State for Business, Enterprise and Regulatory Reform and the Financial Services Secretary to the Treasury announced a review to recommend measures to improve the corporate governance of UK banks, particularly with regard to risk management. The final report A review of corporate governance in UK banks and other financial industry entities: Final recommendations, authored by Sir David Walker, was published on 26 November 2009.

The report is available at (available at: https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/ukgwa/+/http:/www.hm-treasury.gov.uk/d/walker_review_261109.pdf)

[9] https://www.icaew.com/technical/corporate-governance/codes-and-reports/walker-report

[10] https://www.oecd.org/daf/ca/Corporate-Governance-Principles-ENG.pdf

[11] https://www.icgn.org/sites/default/files/2021-06/ICGN%20Global%20Stewardship%20Principles%202020_1.pdf

[12] See discussion in Page 87, Figure 3.16 of OECD Factbook here: https://www.oecd.org/corporate/OECD-Corporate-Governance-Factbook.pdf

[13] See: https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm200203/cmselect/cmtrdind/439/439ap09.htm

[14] See, Annex 8 of the Walker Report, available here: https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/ukgwa/+/http:/www.hm-treasury.gov.uk/d/walker_review_261109.pdf

[15] See: https://www.icaew.com/technical/corporate-governance/codes-and-reports/myners-report

[16] Ibid.

[17]https://www.frc.org.uk/getattachment/e223e152-5515-4cdc-a951-da33e093eb28/UK-Stewardship-Code-July-2010.pdf

[18] https://cgov.pt/images/ficheiros/2018/the_uk_stewardship_code_september_2012.pdf

[19]https://www.frc.org.uk/getattachment/5aae591d-d9d3-4cf4-814a-d14e156a1d87/Stewardship-Code_Dec-19-Final-Corrected.pdf

[20] https://isgframework.org/stewardship-principles/

[21] https://eur-lex.europa.eu/EN/legal-content/summary/shareholder-rights-directive.html

[22] https://acsi.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/ASSET-OWNER-CODE-stewardship.pdf

[23]https://www.stewardshipasia.com.sg/docs/saclibraries/default-document-library/ssp_for-20responsible-20investor-202-0-1-.pdf?sfvrsn=82133969_3

[24] https://indiankanoon.org/doc/730804/

[25] https://www.rbi.org.in/Scripts/BS_PressReleaseDisplay.aspx?prid=36817

[26] https://www.irdai.gov.in/ADMINCMS/cms/whatsNew_Layout.aspx?page=PageNo3096&flag=1

[27] https://www.irdai.gov.in/ADMINCMS/cms/whatsNew_Layout.aspx?page=PageNo4045&flag=1

[28]https://www.pfrda.org.in/writereaddata/links/circular-%20common%20stewardship%20code%2004-05-186ec9a3b4-566b-4881-b879-c5bf0b9e448a.pdf

[29]https://www.sebi.gov.in/legal/circulars/dec-2019/stewardship-code-for-all-mutual-funds-and-all-categories-of-aifs-in-relation-to-their-investment-in-listed-equities_45451.html

[30] https://www.sebi.gov.in/legal/circulars/mar-2010/circular-for-mutual-funds_2019.html

[31]https://www.sebi.gov.in/legal/circulars/mar-2014/enhancing-disclosures-investor-education-and-awareness-campaign-developing-alternative-distribution-channels-for-mutual-fund-products-etc_26537.html

[32]https://www.sebi.gov.in/legal/circulars/mar-2021/circular-on-guidelines-for-votes-cast-by-mutual-funds_49405.html

[33] IRDAI mandates the same, if the insurer’s shareholding is 3% and above (in case insurer’s AUM is upto Rs. 2,50,000 crores), and if the shareholding is 5% and above (in case insurer’s AUM is above Rs. 2,50,000 crores)

[34] Corporate governance matters, changes to capital structure, stock option plans, management compensation issues, social and corporate responsibility issues, appointment/removal of directors, related party transactions, etc.

[35] Circular on “Voting Policy on Assets held by National Pension System Trust” in 2017, available at https://www.pfrda.org.in/myauth/admin/showimg.cshtml?ID=1145, also mentioned in the PFRDA’s Stewardship Code.

[36] See “Shareholder Stewardship in India: The Desiderata” by Umakanth Varotill (March, 2020), here: https://ecgi.global/sites/default/files/working_papers/documents/varottilfinal.pdf

[37] See for instance, “Are MFs serious about SEBI’s Stewardship Code” by M Krishnamoorthy and VR Narshimhan, published in The Hindu businessline, available at: https://www.thehindubusinessline.com/opinion/are-mfs-serious-about-sebis-stewardship-code/article65084621.ece

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!