Mortgage on movable property – whether another lucrative option for lenders?

– Sikha Bansal, Partner & Shraddha Shivani, Executive | corplaw@vinodkothari.com

Introduction

Pledge[1], hypothecation, mortgage – these are all forms of security interest[2], albeit with different features. Although the common objective of any form of security interest is to create a right in rem[3] (rather than in personam[4]) in favour of the lender, the effectiveness of the security interest would depend on the extent of overarching rights created by such security interest in favour of the lender. In another article[5], we have drawn a quick snapshot of the characteristics of each form of security interest. For instance, in hypothecation, the lender does not have any right of possession or any beneficial interest in the property, and the lender’s rights are limited to cause a sale on default; on the other hand, a mortgage (depending upon the type) may have far better rights – including the right to have the title, beneficial interest, etc. In fact, as we discuss elaborately in this article, a mortgage has several motivations for the lender.

However, a conventional notion around mortgages has been that the concept of ‘mortgage’ is only applicable to immovable property. This common view arises in view of explicit provisions under the Transfer of Property Act, 1882 (‘TP Act’). On the other hand, there are no written/codified provisions on mortgage of movable property. It is not that the Courts have not discussed and debated on the same. There have been ample opportunities before the Courts (as this article highlights), wherein Courts have upheld mortgages of movable properties as well. As such, it cannot be said that there has not been any decisive jurisprudence around the subject, however, the recent ruling of Supreme Court in PTC India Financial Services Limited v. Venkateshwar Kari and Another strongly revives the discussion and reinforces the argument that ‘mortgage of movables’ is perfectly possible, although not exactly in terms of the Contract Act; however, under common law principles of equity and natural justice. In fact, in his book Securitisation, Asset Reconstruction and Enforcement of Security Interests, Vinod Kothari, has discussed about ‘chattel mortgages’.

Here, it is important to understand the relevance of this discussion. As we discuss below, a mortgage is seen as the strongest form of security interest – a pledge or a hypothecation create much lesser rights in favour of the secured lender. Hence, from a lender’s perspective, it is always beneficial to have ‘better’ rights in terms of beneficial interest and control. Also, mortgages can be of various kinds (as discussed below), hence, the parties may have the flexibility to structure and opt for a suitable form of security interest.

The article thus, studies the jurisprudence around mortgage of movable property, and the principles which must be followed in order to effect the same. The article also studies how the PTC India ruling has revived the discussion around mortgage of movables. However, before we do so, it would be extremely important to understand the features of a mortgage and how a mortgage can be used as a superior tool of security interest.

Mortgage – meaning and types

In terms of section 58(a) of the TP Act, mortgage has been defined as, “ A mortgage is the transfer of an interest in specific immovable property for the purpose of securing the payment of money advanced or to be advanced by way of loan, an existing or future debt, or the performance of an engagement which may give rise to a pecuniary liability. ”

Going by the definition above, a mortgage has these essential features –

- Transfer of an interest:

There is a difference when an interest is merely ‘created’, and when an interest is actually ‘transferred’. When a debt is secured by a property, it means that an interest of the lender has been created in such collateral property. While this interest is created as soon as the agreement is executed, the interest is transferred only in the event of a default.

The Andhra High Court in the case of Md. Sultan And Ors. vs Firm Of Rampratap Kannyalal[6] held that the mortgage a general but limited properly is transferred to the creditor, whereas a special property passes under a pledge. In the recent PTC India case (supra), the Supreme Court clearly states that “under a mortgage there is transfer of the right of the property by way of security”.

- Specific immovable property:

Where there is an agreement between the lender and the borrower that in the event of non-repayment of debt, the lender will have the right to recover his debt by causing a sale of the borrower’s property, the same would not constitute a mortgage. For there to be a mortgage, there must be a clearly defined property. In other words, a mortgage cannot be executed if it relates to the general estate only.

Further, under the TP Act, such property must be immovable. It is not just the TP Act but also common sense which dictates that when there is no specific property defined in the mortgage deed, creating and enforcing a security interest in such vaguely defined property would be impossible.

- Purpose is securing payment of money:

A mortgage is executed to secure a debt. The consideration of a mortgage may be of three kinds: (1) money advanced or to be advanced by way of loan; (2) an existing or future debt; or (3) the performance of an engagement giving rise to a pecuniary liability.[7] Thus, the existence of a relationship of a lender and a borrower is necessary in the case of a mortgage and that is what distinguishes it from a sale. The mortgaged property acts as a surety of the recovery of the debt amount either by repayment or by cause of sale.

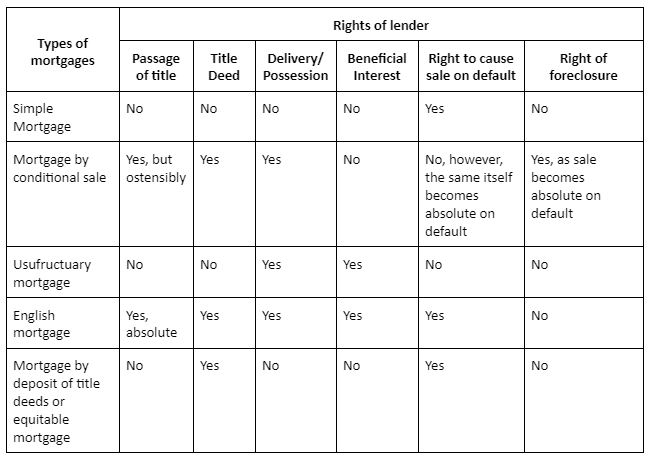

While every mortgage has the above common features; it can take several forms. The TP Act talks about several types of mortgages with certain distinguishing features, as indicated below –

As can be seen above, a simple mortgage is the most basic avatar of a mortgage – there is no delivery, no possession, no transfer of title, but merely a right to ‘cause’ sale. This is the only ‘interest’ which is transferred in this type of mortgage. Also, a mortgagee does not have the right to sell the property but the right to cause the property to be sold—which obviously means only by decree of a Court. An equitable mortgage is evidenced by deposit of title deeds, and gets the same force and features under law as a simple mortgage (see, section 96 of TP Act)

A usufructuary mortgage devolves better rights than a simple mortgage – as the mortgagee gets delivery, possession, as well as the right to enjoy the usufructs (fruits of use).

However, neither a simple mortgage nor a usufructuary mortgage envisage transfer of title. A mortgage by conditional sale, on the other hand, calls for an ostensible (that is, not truly there) sale; hence there is a transfer of title. However, such title is transferred merely as ‘security’ (the third feature of mortgage as discussed above). A rather stronger form is English mortgage, which calls for absolute (and not ostensible) sale of property to the mortgagee, to be transferred back if repayment is duly made.

The aforesaid features are intrinsically linked to the mortgagee’s right of foreclosure – as discussed below.

The opposite forces of right of redemption vs. right of foreclosure

Mortgagor has a right of redemption available under section 60 of TP Act. Such right is a statutory and legal right based upon equitable principles, and is available to the mortgagor until the mortgagee forecloses or sells the property. In fact, the well established rule “once a mortgage, always a mortgage” has been quoted and upheld in multiple Supreme Court rulings over the years.[8] A mortgage cannot be made irredeemable and a provision to that effect is void.

As against mortgagor’s right of redemption, is the mortgagee’s right of foreclosure or sale:

- Right of foreclosure: Foreclosure is a clog on the mortgagor’s right of redemption (as discussed below), as the mortgagor gets forever debarred of his right to redeem the property. In the absence of a contract to the contrary, the mortgagee has a right to foreclose the property in terms of section 67, by obtaining a decree from the Court where the mortgage is either a mortgage by conditional sale or an anomalous mortgage. In Narayan Deorao Javle v. Krishna and Others the Supreme Court of India had held that the right of redemption and the right of foreclosure are coextensive, therefore, no sooner than a decree for foreclosure is passed, the right to redeem extinguishes. Multiple precedents have upheld the right – see Mahamaya Debi v. Haridas Haldar, Mahendra Mohanlal Mistry v. Mehta Mohanlal Mathurdas, Smt. Savitri Devi v. Smt. Beni Devi And Ors.

As to why such right is only available in a mortgage by conditional sale and an anomalous mortgage, Vinod Kothari explains[9]:

“Obvious enough, the question of foreclosure arises only in cases where the mortgagor makes a transfer of proprietary interest in the property. Therefore, section 67(a) authorises a suit for foreclosure only in case of a mortgage by conditional sale, or an anomalous mortgage where the mortgagee is entitled to foreclose. Suit for foreclosure is not allowed either in a simple mortgage or in English mortgage since in either case, the real right that is transferred by the mortgagor is the right of sale and not the right of ousting the mortgagor from the property. In case of a conditional sale, the understanding of the parties is that on default of the debt, the sale will become absolute—the remedy of foreclosure is to attach finality to such sale being absolute. In case of an usufructuary mortgage, the understanding between the parties was that the mortgagee will continue to enjoy the usufruct until as long as the debt is cleared—therefore, the mortgagee can neither foreclose, nor sell, as the usufruct is what was intended.”

- Right of sale: Right of sale too, can be exercised by obtaining a decree. As can be seen, the remedy of sale and foreclosure are mutually exclusive. For example, in case of a conditional sale, the mortgagee cannot sue for sale—though once he forecloses and becomes the absolute owner, he can do so himself. In an English mortgage or a simple mortgage, the mortgagee can sue for sale but not foreclosure.

Hence, a mortgagee can either foreclose (and then sell), or sell the mortgaged property (depending upon the type of mortgage), and sue for the balance amount.

Mortgage vs. other forms of security interest

The distinction between a pledge and a mortgage is well settled, and established in an array of judicial precedents. The essential distinction between a pledge and a mortgage is that unlike a pledgee, a mortgagee acquires the general property in the thing mortgaged subject to the right of redemption of the mortgagor. In other words, the legal estate in the goods mortgaged passes on to the mortgagee.[10]

In Co-Operative Hindusthan Bank v. Surendra Nath Dey And Ors[11]the Calcutta High Court had held that-

“Story in his book on Bailments, 9th Edn., Section 287 says:

A. mortgage of goods is, at Common Law, distinguishable from a mere pawn. By a grant or conveyance of goods in gage or mortgage the whole legal title passes conditionally to the mortgagees; and if the goods are not redeemed at the time stipulated the title Becomes absolute at law, although equity will interfere to compel a redemption. But in a pledge, a special property only, as we shall presently see, passes to the pledgee, the general property remaining in the pledgor. There is also another distinction. In the case of a pledge of personal property the right of the pledgee is not consummated, except by possession; and ordinarily when that possession is relinquished, the right of the pledgee is extinguished or waived. But in the case of a mortgage of personal property, the right of property passes by the conveyance to the pledgee and possession is not or may not, be essential to create or to support the title.”

On the other hand, a pledge can be distinguished from a hypothecation that in the latter, there is no delivery of the hypothecated goods. Further, similar to pledge, there is no ‘transfer’ of interest in hypothecation.

The Orissa High Court held a similar view in Bhabani Sankar Patra v. State Bank Of India And Anr[12] drew a distinction between a pledge and a hypothecation by observing that:

“The distinction between hypothecation of goods and pledge of goods is well known. In case of pledged goods, the goods are stored in the godown under the lock and key of the Bank under the Bank’s supervision. Thus, the pledged goods remain under the physical possession of the Bank and no withdrawals or additions of the stocks in the godown are permissible without the Bank’s permission. The position with regard to the hypothecated goods is, however, different because these goods are, strictly speaking, not under the lock and key of the Bank but allowed to be kept at the premises of the borrower without any lock and key of the Bank as such but are supposed to be under the constructive possession of the Bank by virtue of deed of hypothecation under which the borrower is obliged to submit regular returns to the Bank indicating the increase and decrease of the value of the said goods to enable the Bank from time to time to determine the drawing of the borrower with regard to it. In law, however, there is no difference with regard to the legal possession of the Bank. In both the cases, the goods are under the constructive possession of the Bank, while in the case of pledge they are also in the actual physical possession of the Bank, but in the case of hypothecated goods they are in actual possession of the borrower subject to the restrictions mentioned above.”

Hence, hypothecation is the least cumbersome kind of security interest for the borrower to create.

In essence, one can draw the following comparison among the 3 common forms of security interest –

| Points of discussion | Hypothecation | Pledge | Mortgage |

| Delivery and possession | No | Yes | Depends on type of mortgage |

| Transfer of general interest in property | No | No | Yes |

| Transfer of title | No, hypothecatee gets only special rights | No, pledgee gets only special rights | Yes, in case of mortgage by conditional sale (ostensible), and English mortgage (absolute) |

| Right to enjoyment or usufructs | No | No | Only in case of usufructuary mortgage |

| Right to accretions | Belongs to hypothecator, unless contracted otherwise | Belongs to pledgor, unless contracted otherwise | Mortgagor will be entitled to any accession occurred during the continuance of mortgage, upon redemption. |

| Lender’s remedies on borrower’s default | Take possession of the hypothecated property and sell to secure debt | Cause sale of the pledged property to secure debt | Foreclosure in case of mortgage by conditional sale/anomalous mortgage. Sale in case of simple mortgage/English mortgage. |

| Right of foreclosure | No | No | Possible – in case of a mortgage by conditional sale and an anomalous mortgage |

| Borrower’s right of redemption | Until actual sale happens | Until actual sale happens | Until foreclosure or actual sale |

| Court intervention | Not required | Not required | Decree for foreclosure/sale needed. See discussion below. |

Therefore, a mortgage can serve better rights to the mortgagee; particularly, if the mortgage is one by conditional sale. As we discuss below, such a mortgage (by conditional sale) can be very relevant in financing arrangements involving movable properties too.

Law on mortgage of movable property

As indicated earlier, mortgage has been conventionally associated with immovable property. Reason being, Chapter IV of the TP Act is dedicated to mortgages of ‘immovable property’ and charges. However, as indicated by several noted commentators and as also held by the judiciary and at several instances, the TP Act is not the only law on mortgages, and ‘mortgage’, as a concept, is equally applicable to movable properties. In fact, ‘chattel mortgage’ has been commonly used to describe mortgages of movable property.

Vinod Kothari, in his Book, explains:

“10.13.2 Chattel Mortgage or Mortgage of Movable Property

Like in case of immovable property, a mortgage of movable property transfers an interest in property to the lender to secure the payment of the obligation of the borrower. There is no question of mortgage by deposit of title deeds in this case, as movable properties do not have any title deeds. Most likely, a chattel mortgage may take the form of a conditional sale, or usufructuary mortgage. There are several instances where a hire-purchase transaction has been construed by courts as a chattel mortgage.”

The concept of chattel mortgage has been around for over hundreds of years. As far back as in 1939, the Virginia Law Review dealt with the concept of chattel mortgages as a then evolving concept of security interest. As is evident from the academic journal, the concept has gone through changes and been subjected to the jurisdiction of English courts over a period of time to carve a place for itself that is different from a mere pledge or a hypothecation.

In PTC India (supra), Supreme Court clearly says,

“Where money is advanced by way of the loan upon the security of goods, the transaction may take the form of a mortgage or pledge. The difference between a pledge and a mortgage of movable property is that while under a pledge there is only a bailment, whereas under a mortgage there is transfer of the right of the property by way of security.”

In the instant case, SC also relied on the following passage in Halsbury’s Laws of England:

“A mortgage of personal chattels is essentially different from a pledge or pawn under which money is advanced upon the security of chattels delivered into the possession of the lender, such delivery of possession being an essential element of the transaction. A mortgage conveys the whole legal interest in the chattels; a pledge or pawn conveys only a special property, leaving the general property in the pledger or pawnor; the pledgee or pawnee never has the absolute ownership of the goods, but has a special property in them coupled with a power of selling and transferring them to a purchaser on default of payment at the stipulated time, if any, or at a reasonable time after demand and non-payment if no time for payment is agreed upon.”

The aforesaid excerpt from Halsbury has also been referred to in various other rulings like Arjun Prasad and Ors. vs Central Bank Of India Ltd.[13], which also cites Mulla’s Transfer of Property Act (Third Edition, 1949) as follows:

“A mortgagee of moveable property is entitled to a decree for sale just as much as a mortgagee of immovable property. A mortgagee of moveable property, if in possession, has a right to sell the property without the intervention of the Court, if after proper notice the mortgagor fails to repay the mortgage money ……………. No particular-formality is necessary in India for the creation of a security on moveable property & a parole mortgage of goods is valid”.

The Bombay High Court in Tehilram Girdharidas v. Longin D’Mello[14] deliberated at length about the manner in which mortgage security in movable goods may be enforced:

“10. We may take it on the authority of all the text-book writers that a mortgage of moveables can be as validly effected by parole as by a writing, and that the immediate effect of such a mortgage is to pass the property in the chattels mortgaged from the mortgagor to the mortgagee. It is altogether unnecessary that actual possession of the chattel should be given. Thus, unlike a mortgage of immovable property, which, no matter what its value, can only be effected in this country by a writing or a transfer of possession, mortgages of chattels, having the effect of immediately transferring the property thereunder from the mortgagors to the mortgagees, can be made by mere parole and without the transfer of possession.”

The Madras High Court in Chinni Venkatachalam Chetti v. Athivarapu Venkatrami Reddi[15] referred tothe remarks in Ex parte Official Receiver In re Morrit (1886) 18 Q.B.D. 222, Cotton, L.J. saying “a mortgage of personal chattels involves in its essence, not the delivery of possession, but a conveyance of title as a security for the debt”.

Courts have also recognised the right of foreclosure in case of movable properties. For example, the Calcutta High Court in Mahamaya Debi v. Haridas Haldar[16] held that the remedy of foreclosure is not just confined to mortgages of land but is equally applicable to mortgages of chattels. In any case, it is safe to conclude that where the title in movable property is not immediately passed on to the mortgagee at the time of mortgage agreement, the lender will at least have the right of foreclosure in the event of default of debt. See also, Bhupati Mohan Das v. Phanindra Chandra Chakravarty[17], Mahamaya Debi v. Haridas Haldar[18].

As to whether such foreclosure in case of a mortgage of movable property would also need a Court order as required for immovable property under TP Act, the Courts do not seem to be taking any different view. In Mahamaya Debi (supra), the Calcutta High Court while upholding the validity of mortgage of chattels, and discussing the relevance of ‘foreclosure’ in such mortgages, noted, “It may be added that if the contention of the mortgagors were to prevail, they might find themselves in a worse position, than what they would occupy under a foreclosure decree; for, if the procedure for foreclosure, with its consequent opportunity to the mortgagor to redeem, is not applicable, the mortgagee may very well contend that the contract between the parties must be strictly enforced and that, as the time for repayment has passed away, the title of the mortgagee to the mortgaged property has become absolute; such a result could hardly have been contemplated by the mortgagors.” Going by this very observation, it appears that the mortgagor may not, all by himself, proceed to foreclose the property (movable or immovable), and would need an order of the Court for the same.

One interesting question to ponder would be whether it is possible to create mortgage on shares. In Arjun Prasad and Ors. vs Central Bank Of India Ltd.[19], the Patna High Court was dealing with a question whether the transaction was a pledge or a mortgage of shares. The Court remarked, “I have already observed that the position in India is somewhat different where shares are goods and therefore pledgeable. There can be a pledge of shares in India, and there can also be a mortgage of shares; whether it is one or the other will depend on the intention of the parties & the circumstances of each case.” As stated in the ruling above, while it is a rare practice, mortgage of shares is possible. By virtue of not being completely covered by the TP Act or the Contracts Act, parties are at liberty to draft the mortgage deed as per their requirements. As long as the arrangement fulfills the basic essential features of a mortgage as mentioned above, and the intention of the parties can be clearly understood and communicated, mortgage on shares may be created in authors’ view.

It is also important to note here that Section 2(1)(h) of the SARFAESI Act, 2002 recognizes the mortgage of movable property and includes it within the meaning of a ‘financial asset’. However, as it appears from section 13(4) of the said Act, ‘foreclosure’ is not one of the measures which can be used by the secured creditor for enforcement of security interest and to realize the secured debt.

How will a mortgage on a movable property work?

Hence, going by the precedents and principles as above, one can envisage the following mechanics for effectuating mortgages on movable property (assuming mortgage by conditional sale is the best way) –

- Creation: There has to be a formal written agreement in place. The same draws inspiration from section 58(c) of the TP Act which says that “no such transaction shall be deemed to be a mortgage, unless the condition is embodied in the document which effects or purports to effect the sale”. The principle would equally apply to a movable property. The agreement should record clear intention of the mortgagor to sell the property solely for the purpose of creating ‘security’ in favour of the mortgagee. Further, to create effective rights in favour of the mortgagee, it is important that the right of foreclosure is not taken away by the agreement.

- During subsistence of financing facility: The mortgagee would continue receiving repayments. The mortgage may or may not call for the mortgagee’s entitlement to usufructs from the property. The same would also depend on the type of property, and agreement between the parties.

- On default: The mortgagee would be entitled to foreclose the property, that is, have the title to the property. This is not possible in case of pledges (as also held by SC in PTC India ruling). Once the property is foreclosed, conditional sale becomes absolute, the mortgagee becomes the absolute owner of the property and shall be entitled to exercise all rights of ownership as were earlier vested with the mortgagor. This would create a strong deterrent against default/non-payment by mortgagor.

Closing remarks

Mortgage is one of the oldest forms of security interest that has developed organically in some form or the other all across the globe and continues to be the backbone of the financial credit system. While the mortgage of movable properties is less popular, however, given the added force a mortgage has, it may witness an increasing interest in the corporate world.

Boasting of superior lender rights, creditors may now be keen on exploring mortgages of movable property where earlier pledge and hypothecation were the norm. However, given that the law around chattel mortgage is judge-made (and mostly sketchy, as discussed above), there would be inherent challenges, which may need further judicial involvement.

[1] See our article ‘Broken Pledge? Apex Court reviews the law on pledges’, where we have discussed the law of pledges as re-emphasised by the Supreme Court in PTC India Financial Services Limited v. Venkateshwar Kari and Another

[2] For elaborate discussion on ‘security interest’, refer Part II of the book, Securitisation, Asset Reconstruction and Enforcement of Security Interests, Vinod Kothari, LexisNexis, 2020

[3] Right in rem is defined as a ‘right in respect of a thing’.

[4] Right in personam is defined as a ‘right against a person’.

[5] See footnote 1.

[6] AIR 1964 AP 201

[7] Chapter 4 of Law of Mortgage, Seventh edition, Rashbehary Ghose, Kamal Law House

[8] This is a doctrine to protect the mortgagor’s right of redemption: It renders all agreements in a mortgage for forfeiture of the right to redeem and also incumbrances of or dealings with the property by the mortgagee as against a mortgagor coming to redeem. In 1902 the well-known maxim, ‘ once a mortgage, always a mortgage, was supplemented by the words ‘and nothing but a mortgage’ added by Lord Davey in the leading case Noakes v. Rice, in which the maxim was explained to mean ‘that a mortgage cannot be made irredeemable and a provision to that effect is void.’ The maxim has been supplemented in the Indian context by the words ‘and therefore always redeemable’, added by Justice Sarkar of the Supreme Court in the case of Seth Ganga Dhar v. Shankarlal. See Achaldas Durgaji Oswal v. Ramvilas Gangabisan Heda . SeeShri Shivdev Singh & Anr v. Sh.Sucha Singh & Anr, Singh Ram (D) Tr.Lr vs Sheo Ram & Ors, Harbans vs Om Prakash And Ors

[9] See Part I, Chapter 10 of Securitisation, Asset Reconstruction and Enforcement of Security Interests, Vinod Kothari, LexisNexis, 2020

[10] This principle has been upheld in various other rulings such as Sri Raja Kakarlapudi Venkata v. Andhra Bank Ltd., PTC India case, Shatzadi Begum Saheba And Ors. v. Girdharilal Sanghi And Ors

[11] 138 Ind Cas 852

[12] AIR 1986 Ori 247, 1986 I OLR 510

[13] AIR 1956 Pat 32

[14] (1916) 18 BOMLR 587

[15] (1940) 2 MLJ 456

[16] (1915) ILR 42 Cal 455

[17] AIR 1935 Cal 756

[18] (1915) ILR 42 Cal 455

[19] AIR 1956 Pat 32

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!