-Siddarth Goel (finserv@vinodkothari.com)

Introduction

“If it looks like a duck, swims like a duck, and quacks like a duck, then it probably is a duck”

The above phrase is the popular duck test which implies abductive reasoning to identify an unknown subject by observing its habitual characteristics. The idea of using this duck test phraseology is to determine the role and function performed by the digital lending platforms in consumer credit.

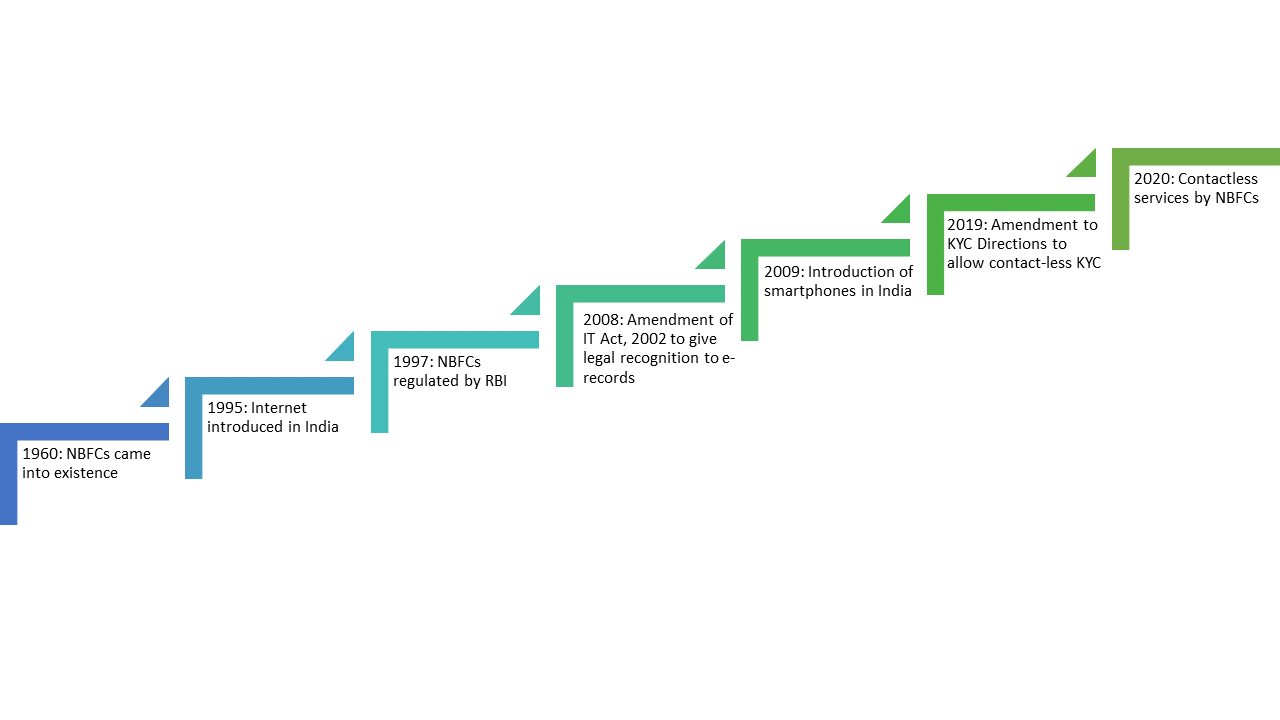

Recently the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) has constituted a working group to study how to make access to financial products and services more fair, efficient, and inclusive.[1] With many news instances lately surrounding the series of unfortunate events on charging of usurious interest rate by certain online lenders and misery surrounding the threats and public shaming of some of the borrowers by these lenders. The RBI issued a caution statement through its press release dated December 23, 2020, against unauthorised digital lending platforms/mobile applications. The RBI reiterated that the legitimate public lending activities can be undertaken by Banks, Non-Banking Financial Companies (NBFCs) registered with RBI, and other entities who are regulated by the State Governments under statutory provisions, such as the money lending acts of the concerned states. The circular further mandates disclosure of banks/NBFCs upfront by the digital lender to customers upfront.

There is no denying the fact that these digital lending platforms have benefits over traditional banks in form of lower transaction costs and credit integration of the unbanked or people not having any recourse to traditional bank lending. Further, there are some self-regulatory initiatives from the digital lending industry itself.[2] However, there is a regulatory tradeoff in the lender’s interest and over-regulation to protect consumers when dealing with large digital lending service providers. A recent judgment by the Bombay High Court ruled that:

“The demand of outstanding loan amount from the person who was in default in payment of loan amount, during the course of employment as a duty, at any stretch of imagination cannot be said to be any intention to aid or to instigate or to abet the deceased to commit the suicide,”[3]

This pronouncement of the court is not under criticism here and is right in its all sense given the facts of the case being dealt with. The fact there needs to be a recovery process in place and fair terms to be followed by banks/NBFCs and especially by the digital lending platforms while dealing with customers. There is a need to achieve a middle ground on prudential regulation of these digital lending platforms and addressing consumer protection issues emanating from such online lending. The regulator’s job is not only to oversee the prudential regulation of the financial products and services being offered to the consumers but has to protect the interest of customers attached to such products and services. It is argued through this paper that there is a need to put in place a better governing system for digital lending platforms to address the systemic as well as consumer protection concerns. Therefore, the onus of consumer protection is on the regulator (RBI) since the current legislative framework or guidelines do not provide adequate consumer protection, especially in digital consumer credit lending.

Global Regulatory Approaches

US

The Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) has laid a Special Purpose National Bank (SPNV) charters for fintech companies.[4] The OCC charter begins reviewing applications, whereby SPNV are held to the same rigorous standards of safety and soundness, fair access, and fair treatment of customers that apply to all national banks and federal savings associations.

The SPNV that engages in federal consumer financial law, i.e. in provides ‘financial products and services to the consumer’ is regulated by the ‘Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB)’. The other factors involved in application assessment are business plans that should articulate a clear path and timeline to profitability. While the applicant should have adequate capital and liquidity to support the projected volume. Other relevant considerations considered by OCC are organizers and management with appropriate skills and experience.

The key element of a business plan is the proposed applicant’s risk management framework i.e. the ability of the applicant to identify, measure, monitor, and control risks. The business plan should also describe the bank’s proposed internal system of controls to monitor and mitigate risk, including management information systems. There is a need to provide a risk assessment with the business plan. A realistic understanding of risk and there should be management’s assessment of all risks inherent in the proposed business model needs to be shown.

The charter guides that the ongoing capital levels of the applicant should commensurate with risk and complexity as proposed in the activity. There is minimum leverage that an SPNV can undertake and regulatory capital is required for measuring capital levels relative to the applicant’s assets and off-balance sheet exposures.

The scope and purpose of CFPB are very broad and covers:

“scope of coverage” set forth in subsection (a) includes specified activities (e.g., offering or providing: origination, brokerage, or servicing of consumer mortgage loans; payday loans; or private education loans) as well as a means for the CFPB to expand the coverage through specified actions (e.g., a rulemaking to designate “larger market participants”).[5]

CFPB is established through the enactment of Dood-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act. The primary function of CFPB is to enforce consumer protection laws and supervise regulated entities that provide consumer financial products and services.

“(5)CONSUMER FINANCIAL PRODUCT OR SERVICES The term “consumer financial product or service” means any financial product or service that is described in one or more categories under—paragraph (15) and is offered or provided for use by consumers primarily for personal, family, or household purposes; or **

“(15)Financial product or service-

(A)In general The term “financial product or service” means—(i)extending credit and servicing loans, including acquiring, purchasing, selling, brokering, or other extensions of credit (other than solely extending commercial credit to a person who originates consumer credit transactions);”

Thus CFPB is well placed as a separate institution to protect consumer interest and covers a wide range of financial products and services including extending credit, servicing, selling, brokering, and others. The regulatory environment has been put in place by the OCC to check the viability of fintech business models and there are adequate consumer protection laws.

EU

EU’s technologically neutral regulatory and supervisory systems intend to capture not only traditional financial services but also innovative business models. The current dealing with the credit agreements is EU directive 2008/48/EC of on credit agreements for consumers (Consumer Credit Directive – ‘Directive’). While the process of harmonising the legislative framework is under process as the report of the commission to the EU parliament raised some serious concerns.[6] The commission report identified that the directive has been partially effective in ensuring high standards of consumer protection. Despite the directive focussing on disclosure of annual percentage rate of charge to the customers, early payment, and credit databases. The report cited that the primary reason for the directive being impractical is because of the exclusion of the consumer credit market from the scope of the directive.

The report recognised the increase and future of consumer credit through digitisation. Further the rigid prescriptions of formats for information disclosure which is viable in pre-contractual stages, i.e. where a contract is to be subsequently entered in a paper format. There is no consumer benefit in an increasingly digital environment, especially in situations where consumers prefer a fast and smooth credit-granting process. The report highlighted the need to review certain provisions of the directive, particularly on the scope and the credit-granting process (including the pre-contractual information and creditworthiness assessment).

China

China has one of the biggest markets for online mico-lending business. The unique partnership of banks and online lending platforms using innovative technologies has been the prime reason for the surge in the market. However, recently the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) and China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission (CBIRC) issued draft rules to regulate online mico-lending business. Under the draft rules, there is a requirement for online underwriting consumer loans fintech platform to have a minimum fund contribution of at least 30 % in a loan originated for banks. Further mico-lenders sourcing customer data from e-commerce have to share information with the central bank.

Australia

The main legislation that governs the consumer credit industry is the National Consumer Credit Protection Act (“National Credit Act”) and the National Credit Code. Australian Securities & Investments Commission (ASIC) is Australia’s integrated authority for corporate, markets, financial services, and consumer credit regulator. ASIC is a consumer credit regulator that administers the National Credit Act and regulates businesses engaging in consumer credit activities including banks, credit unions, finance companies, along with others. The ASIC has issued guidelines to obtain licensing for credit activities such as money lenders and financial intermediaries.[7] Credit licensing is needed for three sorts of entities.

- engage in credit activities as a credit provider or lessor

- engage in credit activities other than as a credit provider or lessor (e.g. as a credit representative or broker)

- engage in all credit activities

The applicants of credit licensing are obligated to have adequate financial resources and have to ensure compliance with other supervisory arrangements to engage in credit activates.

UK

Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) is the regulator for consumer credit firms in the UK. The primary objective of FCA ensues; a secure and appropriate degree of protection for consumers, protect and enhance the integrity of the UK financial system, promote effective competition in the interest of consumers.[8] The consumer credit firms have to obtain authorisation from FCA before carrying on consumer credit activities. The consumer credit activities include a plethora of credit functions including entering into a credit agreement as a lender, credit broking, debt adjusting, debt collection, debt counselling, credit information companies, debt administration, providing credit references, and others. FCA has been successful in laying down detailed rules for the price cap on high-cost short-term credit.[9] The price total cost cap on high-cost short-term credit (HCSTC loans) including payday loans, the borrowers must never have to pay more in fees and interest than 100% of what they borrowed. Further, there are rules on credit broking that provides brokers from charging fees to customers or requesting payment details unless authorised by FCA.[10] The fee charged from customers is to be reported quarterly and all brokers (including online credit broking) need to make clear that they are advertising as a credit broker and not a lender. There are no fixed capital requirements for the credit firms, however, adequate financial resources need to be maintained and there is a need to have a business plan all the time for authorisation purposes.

Digital lending models and concerns in India

Countries across the globe have taken different approaches to regulate consumer lending and digital lending platforms. They have addressed prudential regulation concerns of these credit institutions along with consumer protection being the top priority under their respective framework and legislations. However, these lending platforms need to be looked at through the current governing regulatory framework from an Indian perspective.

The typical credit intermediation could be performed by way of; peer to peer (P2P) lending model, notary model (bank-based) guaranteed return model, balance sheet model, and others. P2P lending platforms are heavily regulated and hence are not of primary concern herein. Online digital lending platforms engaged in consumer lending are of significance as they affect investor’s and borrowers’ interests and series of legal complexions arise owing to their agency lending models.[11] Therefore careful anatomy of these models is important for investors and consumer protection in India.

Should digital lending be regulated?

Under the current system, only banks, NBFCs, and money lenders can undertake lending activities. The regulated banks and NBFCs also undertake online consumer lending either through their website/platforms or through third-party lending platforms. These unregulated third-party digital lending platforms count on their sophisticated credit underwriting analytics software and engage in consumer lending services. Under the simplest version of the bank-based lending model, the fintech lending platform offers loan matching services but the loan is originated in books of a partnering bank or NBFC. Thus the platform serves as an agent that brings lenders (Financial institutions) and borrowers (customers) together. Therefore RBI has mandated fintech platforms has to abide by certain roles and responsibilities of Direct Selling Agent (DSA) as under Fair Practice Code ‘FPC’ and partner banks/NBFCs have to ensure Guidelines on Managing Risks and Code of Conduct in Outsourcing of Financial Service (‘outsourcing code’).[12] In the simplest of bank-based models, the banks bear the credit risk of the borrowers and the platform earns their revenues by way of fees and service charges on the transaction. Since banks and NBFCs are prudentially regulated and have to comply with Basel capital norms, there are not real systemic concerns.

However, the situation alters materially when such a third-party lending platform adopts balance sheet lending or guaranteed return models. In the former, the servicer platform retains part of the credit risk on its book and could also give some sort of loss support in form of a guarantee to its originating partner NBFC or bank.[13] While in the latter case it a pure guarantee where the third-party lending platform contractually promises returns on funds lent through their platforms. There is a devil in detailed scrutiny of these business models. We have earlier highlighted the regulatory issues in detail around fintech practices and app-based lending in our write up titled ‘Lender’s piggybacking: NBFCs lending on Fintech platforms’ gurantees’.

From the prudential regulation perspective in hindsight, banks, and NBFCs originating through these third-party lending platforms are not aware of the overall exposure of the platforms to the banking system. Hence there is a presence of counterparty default risk of the platform itself from the perspective of originating banks and NBFCs. In a real sense, there is a kind of tri-party arrangement where funds flow from ‘originator’ (regulated bank/NBFC) to the ‘platform’ (digital service provider) and ultimately to the ‘borrower'(Customer). The unregulated platform assumes the credit risk of the borrower, and the originating bank (or NBFC) assumes the risk of the unregulated lending platform.

Curbing unregulated lending

In the balance sheet and guaranteed return models, an undercapitalized entity takes credit risk. In the balance sheet model, the lending platform is directly taking the credit risk and may or may not have to get itself registered as NBFC with RBI. The registration requirement as an NBFC emanates if the financial assets and financial income of the platform is more than 50 % of its total asset and income of such business (‘principal business criteria’ see footnote 12). While in the guaranteed return model there is a form of synthetic lending and there is absolutely no legal requirement for the lending platform to get themselves registered as NBFC. The online lending platform in the guaranteed return model serves as a loan facilitator from origination to credit absorption. There is a regulatory arbitrage in this activity. Since technically this activity is not covered under the “financial activity” and the spread earned in not “financial income” therefore there is no requirement for these entities to get registered as NBFCs.[14]

Any sort of guarantee or loss support provided by the third-party lending platform to its partner bank/NBFC is a synthetic exposure. In synthetic lending, the digital lending platform is taking a risk on the underlying borrower without actually taking direct credit risk. Additionally, there are financial reporting issues and conflict of interest or misalignment of incentives, i.e. the entities do not have to abide by IND AS and can show these guarantees as contingent liabilities. On the contrary, they charge heavy interest rates from customers to earn a higher spread. Hence synthetic lending provides all the incentives for these third-party lending platforms to enter into risky lending which leads to the generation of sub-prime assets. The originating banks and NBFCs have to abide by minimum capital requirements and other regulatory norms. Hence the sub-prime generation of consumer credit loans is supplemented by heavy returns offered to the banks. It is argued that the guaranteed returns function as a Credit Default Swap ‘CDS’ which is not regulated as CDS. Thus the online lending platform escapes the regulatory purview and it is shown in the latter part this leads to poor credit discipline in consumer lending and consumer protection is often put on the back burner.

From the prudential regulation perspective restricting banks/NBFCs from undertaking any sort of guaranteed return or loss support protection, can curb the underlying emergence of systemic risk from counterparty default. While a legal stipulation to the effect that NBFCs/Banks lending through the third-party unregulated platform, to strictly lend independently i.e. on a non-risk sharing basis of the credit risk. Counterintuitively, the unregulated online lending platforms have to seek registration as an NBFC if they want to have direct exposure to the underlying borrower, subject to fulfillment of ‘principal business criteria’.[15] Such a governing framework will reduce the incentives for banks and NBFCs to exploit excessive risk-taking through this regulatory arbitrage opportunity.

Ensuring Fairness and Consumer Protection

There are serious concerns of fair dealing and consumer protection aspects that have arisen lately from digital online lending platforms. The loans outsourced by Banks and NBFCs over digital lending platforms have to adhere to the FPC and Outsourcing code.

The fairness in a loan transaction calls for transparent disclosure to the borrower all information about fees/charges payable for processing the loan application, disbursed, pre-payment options and charges, the penalty for delayed repayments, and such other information at the time of disbursal of the loan. Such information should also be displayed on the website of the banks for all categories of loan products. It may be mentioned that levying such charges subsequently without disclosing the same to the borrower is an unfair practice.[16]

Such a legal requirement gives rise to the age-old question of consumer law, yet the most debatable aspect. That mere disclosure to the borrower of the loan terms in an agreement even though the customer did not understand the underlying obligations is a fair contract (?) It is argued that let alone the disclosures of obligations in digital lending transactions, customers are not even aware of their remedies. Under the current RBI regulatory framework, they have the remedy to approach grievance redressal authorities of the originating bank/NBFC or may approach the banking ombudsman. However, things become even more peculiar in cases where loans are being sourced or processed through third-party digital platforms. The customers in the majority of the cases are unaware of the fact that the ultimate originator of the loan is a bank/NBFC. The only remedy for such a customer is to seek refuge under the Consumer Protection Act 2019 by way of proving the loan agreement is the one as ‘unfair contract’.

“2(46) “unfair contract” means a contract between a manufacturer or trader or service provider on one hand, and a consumer on the other, having such terms which cause significant change in the rights of such consumer, including the following, namely:— (i) requiring manifestly excessive security deposits to be given by a consumer for the performance of contractual obligations; or (ii) imposing any penalty on the consumer, for the breach of contract thereof which is wholly disproportionate to the loss occurred due to such breach to the other party to the contract; or (iii) refusing to accept early repayment of debts on payment of applicable penalty; or (iv) entitling a party to the contract to terminate such contract unilaterally, without reasonable cause; or (v) permitting or has the effect of permitting one party to assign the contract to the detriment of the other party who is a consumer, without his consent; or (vi) imposing on the consumer any unreasonable charge, obligation or condition which puts such consumer to disadvantage;”

It is pertinent to note that neither the scope of consumer financial agreements is regulated in India, nor are the third-party digital lending platforms required to obtain authorisation from RBI. There are instances of high-interest rates and exorbitant fees charged by the online consumer lending platforms which are unfair and detrimental to customers’ interests. The current legislative framework provides that the NBFCs shall furnish a copy of the loan agreement as understood by the borrower along with a copy of each of all enclosures quoted in the loan agreement to all the borrowers at the time of sanction/disbursement of loans.[17] However, like the persisting problem in the EU 2008/48/EC directive, even FPC is not well placed to govern digital lending agreements and disclosures. Taking a queue from the problems recognised by the EU parliamentary committee report. There is no consumer benefit in an increasingly digital environment, especially in situations where there are fast and smooth credit-granting processes. The pre-contractual information on the disclosure of annualised interest rate and capping of the total cost to a customer in consumer credit loans is central to consumer protection.

The UK legislation has been pro-active in addressing the underlying unfair contractual concerns, by fixation of maximum daily interest rates and maximum default fees with an overall cost cap of 100% that could be charged in short-term high-interest rates loan agreements. It is argued that in this Laissez-faire world the financial services business models which are based on imposing an unreasonable charge, obligations that could put consumers to disadvantage should anyways be curbed. Therefore a legal certainty in this regard would save vulnerable customers to seek the consumer court’s remedy in case of usurious and unfair lending.

The master circular on loan and advances provide for disclosure of the details of recovery agency firms/companies to the borrower by the originating bank/NBFC.[18] Further, there is a requirement for such recovery agent to disclose to the borrower about the antecedents of the bank/NBFC they are recovering for. However, this condition is barely even followed or adhered to and the vulnerable consumers are exposed to all sorts of threats and forceful tactics. As one could appreciate in jurisdictions of the US, UK, Australia discussed above, consumer lending and ancillary services are under the purview of concerned regulators. From the customer protection perspective, at least some sort of authorization or registration requirement with the RBI to keep the check and balances system in place is important for consumer protection. The loan recovery business is sensitive hence there is a need for a proper guiding framework and/or registration requirement of the agents acting as recovery agents on behalf of banks/NBFCs. The mere registration requirement and revocation of same in case of unprofessional activities will serve as a stick to check their consumer dealing practices.

The financial services intermediaries (other than Banks/NBFCs) providing services like credit broking, debt adjusting, debt collection, debt counselling, credit information, debt administration, credit referencing to be licensed by the regulator. The banks/NBFCs dealing with the licensed market intermediaries would go much farther in the successful implementation of FPC and addressing consumer protection concerns from the current system.

Conclusion

From the perspective of sound financial markets and fair consumer practices, it is always prudent to allow only those entities in credit lending businesses that are best placed to bear the credit risk and losses emanating from them. Thus, there is a dearth of a comprehensive legislative framework in consumer lending from origination to debt collection and its administration including the business of providing credit references through digital lending platforms. There may not be a material foreseeable requirement for regulating digital lending platforms completely. However, there is a need to curb synthetic lending by third-party digital lending platforms. Since a risk-taking entity without adequate capitalization will tend to get into generating risky assets with high returns. The off-balance sheet guarantee commitments of these entities force them to be aggressive towards their customers to sustain their businesses. This write-up has explored various regulatory approaches, where jurisdictions like the US and UK, and Australia being the good comparable in addressing consumer protection concerns emanating from online digital lending platforms. Henceforth, a well-framed consumer protection system especially in financial products and services would go much farther in the development and integration of credit through digital lending platforms in the economy.

[1] Reserve Bank of India – Press Releases (rbi.org.in), dated January 13, 2020

[2] Digital lending Association of India, Code of Conduct available at https://www.dlai.in/dlai-code-of-conduct/

[3] Rohit Nalawade Vs. State of Maharashtra High Court of Bombay Criminal Application (APL) NO. 1052 OF 2018 < https://images.assettype.com/barandbench/2021-01/cf03e52e-fedd-4a34-baf6-25dbb55dbf29/Rohit_Nalawade_v__State_of_Maharashtra___Anr.pdf>

[4] https://www.occ.gov/topics/supervision-and-examination/responsible-innovation/comments/pub-special-purpose-nat-bank-charters-fintech.pdf

[5] 12 USC 5514(a); Pay day loans are the short term, high interest bearing loans that are generally due on the consumer’s next payday after the loan is taken.

[6] EU, ‘Report from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council: on the implementation of Directive 2008/48/EC on credit agreement for consumers’, dated November, 05, 2020, available at < https://ec.europa.eu/transparency/regdoc/rep/1/2020/EN/COM-2020-963-F1-EN-MAIN-PART-1.PDF>

[7] https://asic.gov.au/for-finance-professionals/credit-licensees/applying-for-and-managing-your-credit-licence/faqs-getting-a-credit-licence/

[8] FCA guide to consumer credit firms, available at < https://www.fca.org.uk/publication/finalised-guidance/consumer-credit-being-regulated-guide.pdf>

[9] FCA, ‘Detailed rules for price cap on high-cost short-term credit’, available at < https://www.fca.org.uk/publication/policy/ps14-16.pdf>

[10] FCA, Credit Broking and fees, available at < https://www.fca.org.uk/publication/policy/ps14-18.pdf>

[11] Bank of International Settlements ‘FinTech Credit : Market structure, business models and financial stability implications’, 22 May 2017, FSB Report

[12] See our write up on ‘ Extension of FPC on lending through digital platforms’ , available at < http://vinodkothari.com/2020/06/extension-of-fpc-on-lending-through-digital-platforms/>

[13] Where the unregulated platform assumes the complete credit risk of the borrower there is no interlinkage with the partner bank and NBFC. The only issue that arises is from the registration requirement as NBFC which we have discussed in the next section. Also see our write up titled ‘Question of Definition: What Exactly is an NBFC’ available at http://vinodkothari.com/nbfcs/definition-of-nbfcs-concept-of-principality-of-business/

[14] The qualifying criteria to register as an NBFC has been discussed in our write up titled ‘Question of Definition: What Exactly is an NBFC’ available at http://vinodkothari.com/nbfcs/definition-of-nbfcs-concept-of-principality-of-business/

[15] see our write up titled ‘Question of Definition: What Exactly is an NBFC’ available at http://vinodkothari.com/nbfcs/definition-of-nbfcs-concept-of-principality-of-business/

[16] Para 2.5.2, RBI Guidelines on Fair Practices Code for Lender

[17] Para 29 of the guidelines on Fair Practices Code, Master Direction on systemically/non-systemically important NBFCs.

[18] Para 2.6, Master Circular on ‘Loans and Advances – Statutory and Other Restrictions’ dated July 01, 2015;

Our Other Related Write-Ups

Lenders’ piggybacking: NBFCs lending on Fintech platforms’ guarantees – Vinod Kothari Consultants

Extension of FPC on lending through digital platforms – Vinod Kothari Consultants

Fintech Framework: Regulatory responses to financial innovation – Vinod Kothari Consultants

One-stop guide for all Regulatory Sandbox Frameworks – Vinod Kothari Consultants