RBI to regulate operation of payment intermediaries

Guidelines on regulation of Payment Aggregators and Payment Gateways issued

-Mridula Tripathi (finserv@vinodkothari.com)

Background

In this era of digitalisation, the role of intermediaries who facilitate the payments in an online transaction has become pivotal. These intermediaries are a connector between the merchants and customers, ensuring the collection and settlement of payment. In the absence of any direct guidelines and adequate governance practices regulating the operations of these intermediaries, there was a need to review the existing instructions issued in this regard by the RBI. Thus, the need of regulating these intermediaries has been considered cardinal by the regulator.

RBI had on September 17, 2019 issued a Discussion Paper on Guidelines for Payment Gateways and Payment Aggregators[1] covering the various facets of activities undertaken by Payment Gateways (PGs) and Payment Aggregators (PAs) (‘Discussion Paper’). The Discussion Paper further explored the avenues of regulating these intermediaries by proposing three options, that is, regulation with the extant instructions, limited regulation or full and direct regulation to supervise the intermediaries.

In this regard, the final guidelines have been issued by the RBI on March 17, 2020 which shall be effective from April 1, 2020[2], for regulating the activities of PAs and providing technology-related recommendations to PGs (‘Guidelines’).

In this article we shall discuss the concept of Payment Aggregator and Payment Gateway. Further, we intend to cover the applicability, eligibility norms, governance practices and reporting requirements provided in the aforesaid guidelines.

Concept of Payment Aggregators and Payment Gateways

In common parlance Payment Gateway can be understood as a software which enables online transactions. Whenever the e-interface is used to make online payments, the role of this software infrastructure comes into picture. Thinking of it as a gateway or channel that opens whenever an online transaction takes place, to traverse money from the payer’s credit cards/debit cards/ e-wallets etc to the intended receiver.

Further, the role of a Payment Aggregator can be understood as a service provider which includes all these Payment Gateways. The significance of the Payment Aggregators lies in the fact that Payment Gateway is a mere technological base which requires a back-end operator and this role is fulfilled by the Payment Aggregator.

A merchant (Seller) providing goods/services to its target customer would require a Merchant Account opened with the bank to accept e-payment. Payment Aggregator can provide the same services to several merchants through one escrow account without the need of opening multiple Merchant Accounts in the bank for each Merchant.

The concept of PA and PG as defined by the RBI is reproduced herein below:

PAYMENT AGGREGATORS (PAs) means the entities which enable e-commerce sites and merchants to meet their payment obligation by facilitating various payment options without creation of a separate payment integration system of their own. These PAs aggregate the funds received as payment from the customers and pass them to the merchants after a certain time period.

PAYMENT GATEWAYS (PGs) are entities that channelize and process an online payment transaction by providing the necessary infrastructure without actual handling of funds.

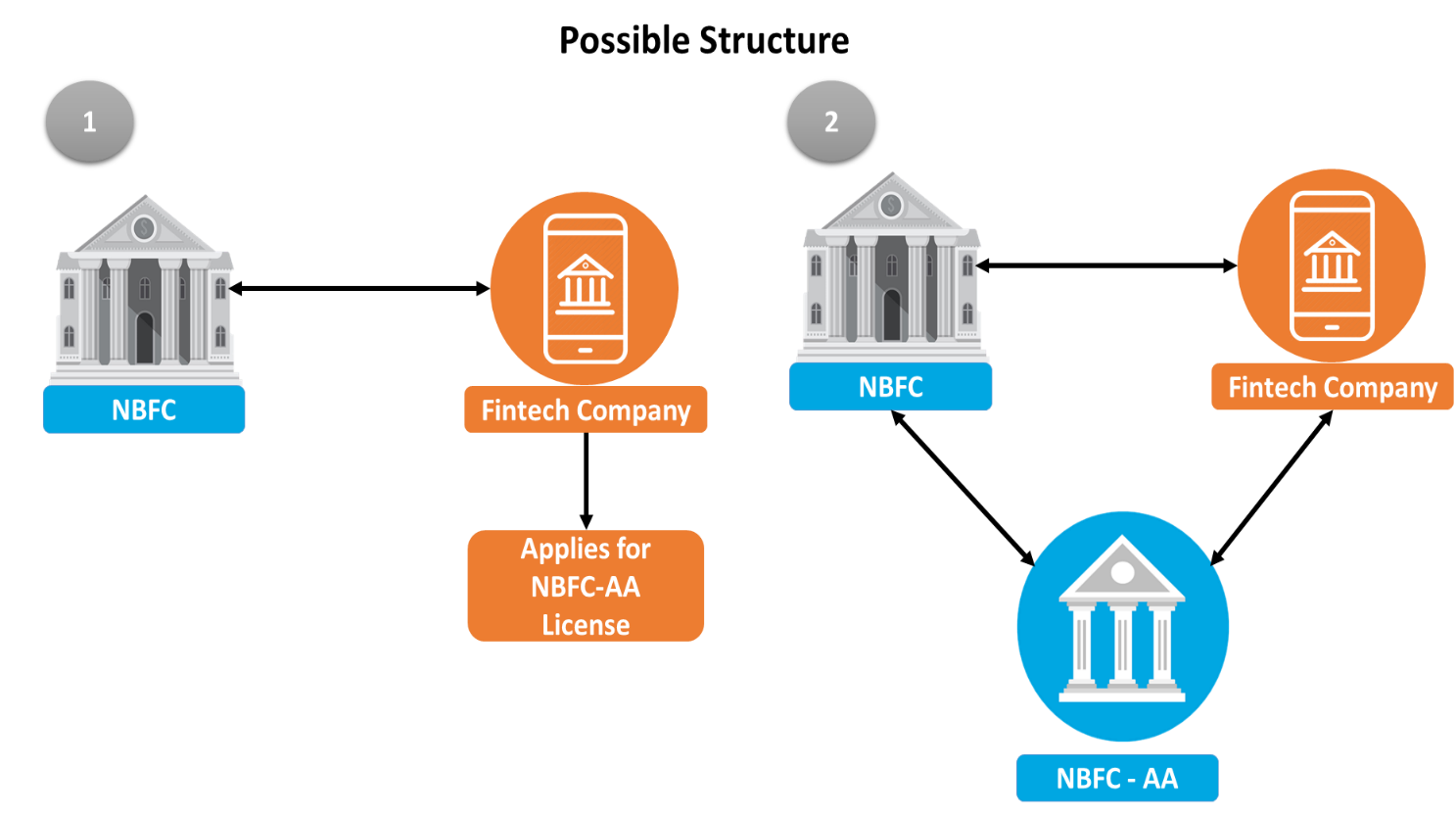

The Guidelines have also clearly distinguished Payment Gateways as providers of technological infrastructure and Payment Aggregators as the entities facilitating the payment. At present, the existing PAs and PGs have a variety of technological set-up and their infrastructure also keeps changing with time given the business objective for ensuring efficient processing and seamless customer experience. Some of the e-commerce market places have leveraged their market presence and started offering payment aggregation services as well. Though the primary business of an e-commerce marketplace does not come within the regulatory purview of RBI, however, with the introduction of regulatory provisions for PAs, the entities will end up being subjected to dual regulation. Hence, it is required to separate these two activities to enable regulatory supervision over the payment aggregation business.

The extant regulations[3] on opening and operation of accounts and settlement of payments for electronic payment transactions involving intermediarieswe were applicable to intermediaries who collect monies from customers for payment to merchants using any electronic / online payment mode. The Discussion Paper proposed a review of the said regulations and based on the feedback received from market participants, the Guidelines have been issued by RBI.

Coverage of Guidelines

RBI has made its intention clear to directly regulate PAs (Bank & Non-Bank) and it has only provided an indicative baseline technology related recommendation. The Guidelines explicitly exclude Cash on Delivery (CoD) e-commerce model from its purview. Surprisingly, the Discussion Paper issued by RBI in this context intended on regulating both the PAs & PGs, however, since PGs are merely technology providers or outsourcing partners they have been kept out of the regulatory requirements.

The Guidelines come into effect from April 1, 2020, except for requirements for which a specific deadline has been prescribed, such as registration and capital requirements.

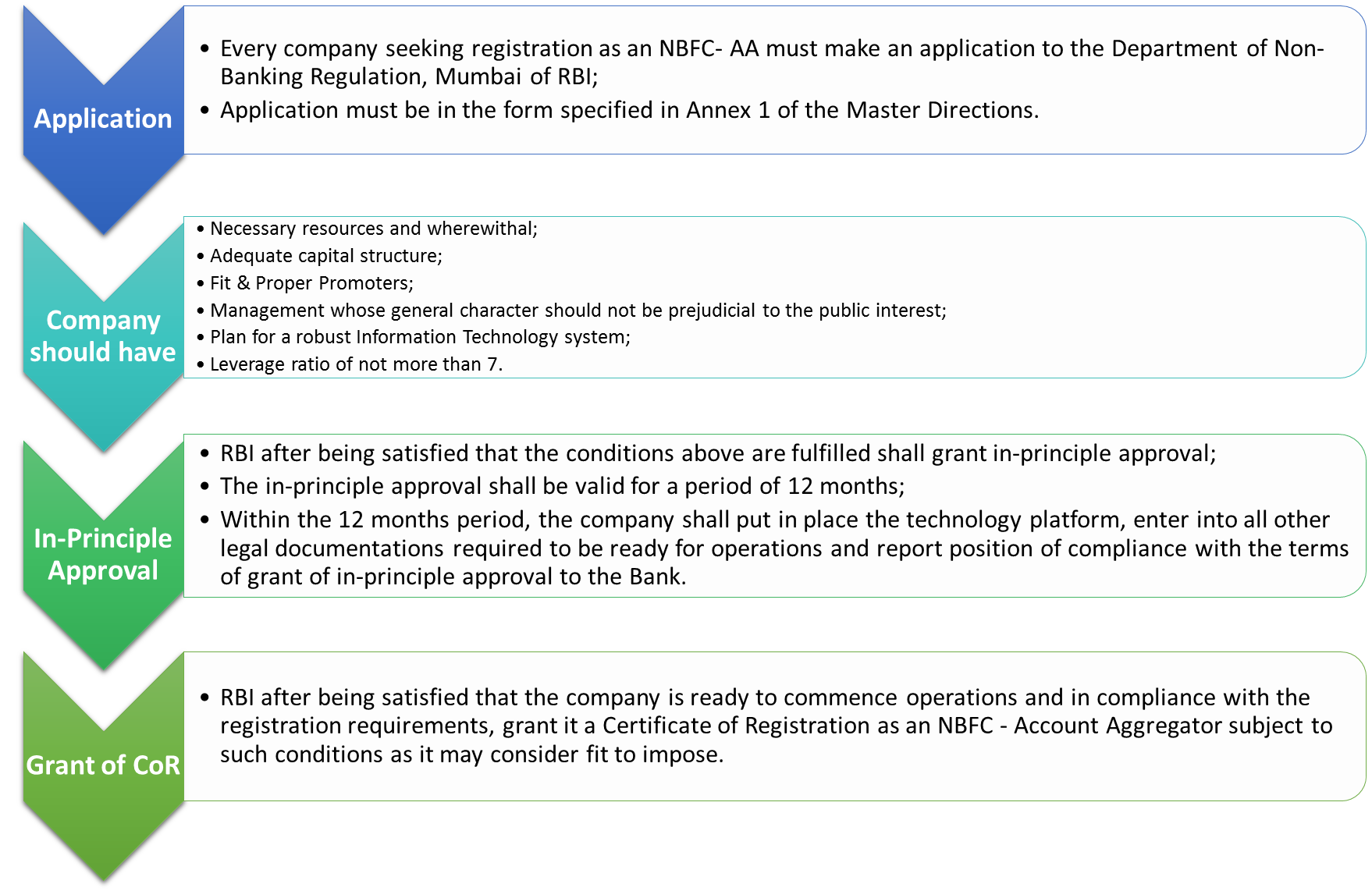

Registration requirement

Payment Aggregators are required to fulfil the requirements as provided under the Guidelines within the prescribed timelines. The Guidelines require non-bank entities providing PA services to be incorporated as a company under the Companies Act, 1956/2013 being able of carrying out the activity of operating as a PA, as per its charter documents such as the MoA. Such entities are mandatorily required to register themselves with RBI under the Payment and Settlement Systems Act, 2007 (‘PSSA, 2007’) in Form-A. However, a deadline of June 30, 2021 has been provided for existing non-bank PAs.

Capital requirement

RBI has further benchmarked the capital requirements to be adhered by existing and new PAs. According to which the new PAs at the time of making the application and existing PAs by March 31, 2021 must have a net worth of Rs 15 crore and Rs 25 crore by the end of third financial year i.e. March 31, 2023 and thereafter. Any non-compliance with the capital requirements shall lead to winding up of the business of PA.

As a matter of fact, the Discussion Paper issued by RBI, proposed a capital requirement of Rs 100 crore which seems to have been reduced considering the suggestion received from the market participants.

To supervise the implementation of these Guidelines, there is a certification to be obtained from the statutory auditor, to the effect certifying the compliance of the prescribed capital requirements.

Fit and proper criteria

The promoters of PAs are expected to fulfil fit and proper criteria prescribed by RBI and a declaration is also required to be submitted by the directors of the PAs. However, RBI shall also assess the ‘fit and proper’ status of the applicant entity and the management by obtaining inputs from various regulators.

Policy formulation

The Guidelines further require formulation and adoption of a board approved policy for the following:

- merchant on-boarding

- disposal of complaints, dispute resolution mechanism, timelines for processing refunds, etc., considering the RBI instructions on Turn Around Time (TAT)

- information security policy for the safety and security of the payment systems operated to implement security measures in accordance with this policy to mitigate identified risks

- IT policy(as per the Baseline Technology-related Recommendations)

Grievance redressal

The Guidelines have put in place mandatory appointment of a Nodal Officer to handle customer and regulator grievance whose details shall be prominently displayed on the website thus implying good governance in its very spirit. This is similar to the requirement for NBFCs who are required to appoint a Nodal Officer. Also, it is required that the dispute resolution mechanism must contain details on types of disputes, process of dealing with them, Turn Around Time (TAT) for each stage etc.

However, in this context, the Discussion Paper provided for a time period of 7 working days to promptly handle / dispose of complaints received by the customer and the merchant.

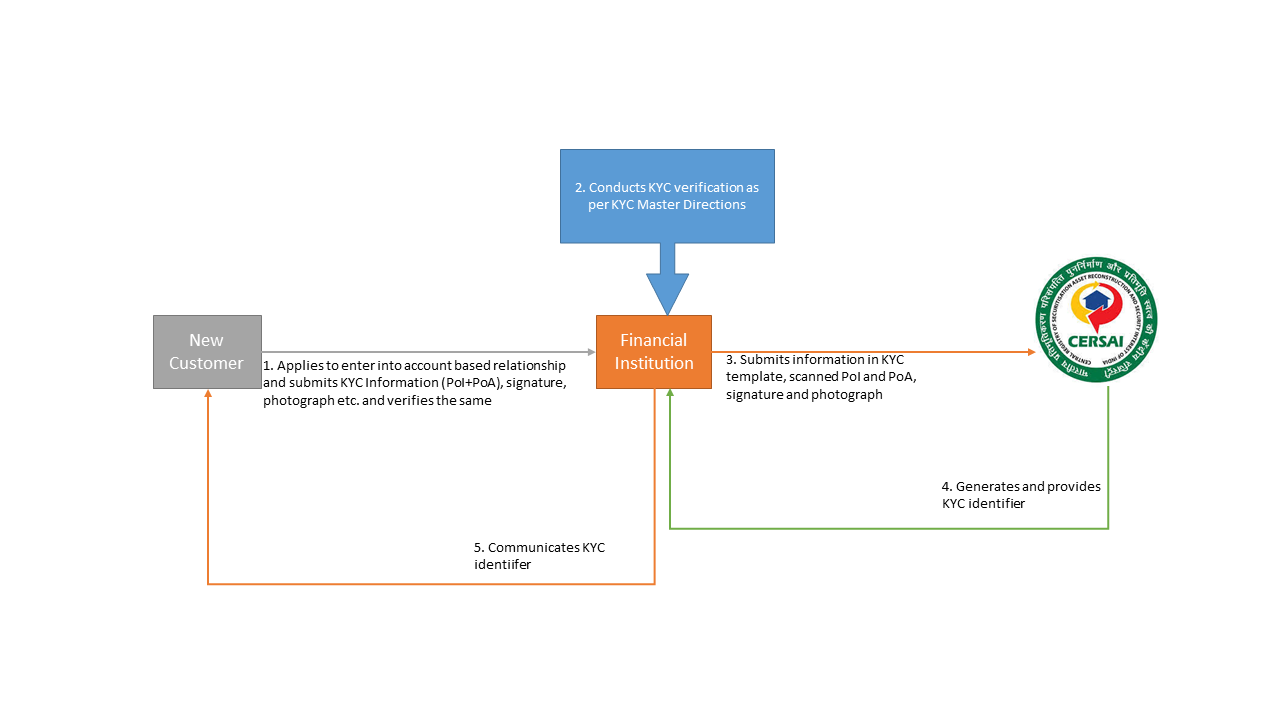

Merchant on boarding and KYC compliance

To avoid malicious intent of the merchants, PAs should undertake background and antecedent check of the merchants and are responsible to check Payment Card Industry-Data Security Standard (PCI-DSS) and Payment Application-Data Security Standard (PA-DSS) compliance of the infrastructure of the merchants on-boarded and carry a KYC of the merchants on boarded. It also provides for some mandatory clauses to be incorporated in the agreements to be executed with the merchants.

Risk Management

For the purposes of risk management, apart from adoption of an IS policy, the PAs shall also have a mechanism to monitor, handle and report cyber security incidents and breaches. They are also prohibited to allow online transactions with ATM pin and store customer card credentials on the servers accessed by the merchants and are required to comply with data storage requirements as applicable to Payment System Operators (PSOs).

Reporting Requirements

The Guidelines provide for monthly, quarterly and annual reporting requirement. The annual requirement comprises of certification from a CA and IS audit report and Cyber Security Audit report. The quarterly reporting again provides for certification requirement and the monthly requirement demand a transaction statistic. Also, there shall be reporting requirement in case of any change in management requiring intimation to RBI within 15 days along with ‘Declaration & Undertaking’ by the new directors. Apart from these mainstream reporting requirements there are non-periodic requirements as well.

Additionally, PAs are required to submit the System Audit Report, including cyber security audit conducted by CERTIn empanelled auditors, within two months of the close of their financial year to the respective Regional Office of DPSS, RBI

Escrow Account Mechanism

The Guidelines clearly state that the funds collected from the customers shall be kept in an escrow account opened with any Schedule Commercial Bank by the PAs. And to protect the funds collected from customers the Guidelines state that PA shall be deemed as a ‘Designated Payment System’[4] under section 23A of PSSA, 2007.

Shift from Nodal to Escrow

The Discussion Paper proposed registration, capital requirement, governance, risk management and such other regulations along with the maintenance of a nodal account to manage the funds of the merchants. Further, it acknowledged that in case of nodal accounts, there is no beneficial interest created on the part of the PAs; the fact that they do not form part of the PA’s balance sheet and no interest can be earned on the amount held in these account. The Guidelines are more specific about escrow accounts and do not provide for maintenance of nodal accounts, which seems to indicate a shift from nodal to escrow accounts with the same benefits as nodal accounts and additionally having an interest bearing ‘core portion’. These escrow account arrangements can be with or without a tripartite agreement, giving an option to the merchant to monitor the transactions occurring through the escrow. However, in practice it may not be possible to make each merchant a party to the escrow agreement.

Timelines for settlement to avoid unnecessary delay in payments to Merchants, various timelines have been provided as below:

- Amounts deducted from the customer’s account shall be remitted to the escrow account maintaining bank on Tp+0 / Tp+1 basis. (Tp is the date of debit to the customer’s account against good/services purchased)

- Final settlement with the merchant

- In cases where PA is responsible for delivery of goods / services, the payment to the merchant shall be made on Ts + 1 basis. (Ts is the date of intimation by merchant about shipment of goods)

- In cases where merchant is responsible for delivery, the payment to the merchant shall be on Td + 1 basis. (Td is the date of confirmation by the merchant about delivery of goods)

- In cases where the agreement with the merchant provides for keeping the amount by the PA till expiry of refund period, the payment to the merchant shall be on Tr + 1 basis. (Tr is the date of expiry of refund period)

Also, refund and reversed transactions must be routed back through the escrow account unless as per contract the refund is directly managed by the merchant and the customer has been made aware of the same. A minimum balance requirement equivalent to the amount already collected from customer as per ‘Tp’ or the amount due to the merchant at the end of the day is required to be maintained in the escrow account at any time of the day.

Permissible debits and credits

Similar to the extant regulations, the Guidelines provide a specific list of debits and credits permissible from the escrow account:

- Credits that are permitted

- Payment from various customers towards purchase of goods / services.

- Pre-funding by merchants / PAs.

- Transfer representing refunds for failed / disputed / returned / cancelled transactions.

- Payment received for onward transfer to merchants under promotional activities, incentives, cashbacks etc.

- Debits that are permitted

- Payment to various merchants / service providers.

- Payment to any other account on specific directions from the merchant.

- Transfer representing refunds for failed / disputed transactions.

- Payment of commission to the intermediaries. This amount shall be at pre-determined rates / frequency.

- Payment of amount received under promotional activities, incentives, cash-backs, etc.

The aforesaid list of permitted deposits and withdrawals into an account operated by an intermediary is wider than those allowed under the extant regulations. The facility to pay the amount held in escrow to any other account on the direction of the merchant would now enable cashflow trapping by third party lenders or financier. The merchant will have an option to provide instructions to the PA to directly transfer the funds to its creditors.

The Guidelines expressly state that the settlement of funds with merchants will in no case be co-mingled with other business of the PA, if any and no loans shall be available against such amounts.

No interest shall be payable by the bank on balances maintained in the escrow account, except in cases when the PA enters into an agreement with the bank with whom the escrow account is maintained, to transfer “core portion”[5] of the amount, in the escrow account, to a separate account on which interest is payable. Another certification requirement to be obtained from auditor(s) is for certifying that the PA has been maintaining balance in the escrow account.

Technology-related Recommendations

Several technology related recommendations have been separately provided in the Guidelines and are mandatory for PAs but recommendatory for PGs. These instructions provide for adherence to data security standards and timely reporting of security incidents in the course of operation of a PA. It proposes involvement of Board in formulating policy and a competent pool of staff for better operation along with other governance and security parameters.

Conclusion

With these Guidelines being enforced the online payment facilitated by intermediaries will be regulated and monitored by the RBI henceforth. The prescribed timeline of April 2020 may cause practical difficulties and act as a hurdle for the operations of existing PAs. However, the timelines provided for registration and capital requirements are considerably convenient for achieving the prescribed benchmarks. Since PAs are handling the funds, these Guidelines, which necessitate good governance, security and risk management norms on PAs, are expected to be favourable for the merchants and its customers.

[1] https://www.rbi.org.in/scripts/PublicationReportDetails.aspx?ID=943

[2] https://www.rbi.org.in/Scripts/NotificationUser.aspx?Id=11822&Mode=0

[3] https://www.rbi.org.in/Scripts/NotificationUser.aspx?Id=5379&Mode=0

[4] The Reserve Bank may designate a payment system if it considers that designating the system is in the public interest. The designation is to be by notice in writing published in the Gazette, as per Payment System Regulation Act, 1998

[5] This facility shall be permissible to entities who have been in business for 26 fortnights and whose accounts have been duly audited for the full accounting year. For this purpose, the period of 26 fortnights shall be calculated from the actual business operation in the account. ‘Core Portion’ shall be average of the lowest daily outstanding balance (LB) in the escrow account on a fortnightly (FN) basis, for fortnights from the preceding month 26.

Our other write ups on NBFCs to be referred here http://vinodkothari.com/nbfcs/

Our other similar articles: