Fintech Framework: Regulatory responses to financial innovation

Timothy Lopes, Executive, Vinod Kothari Consultants

The world of financial services is continually witnessing a growth spree evidenced by new and innovative ways of providing financial services with the use of enabling technology. Financial services coupled with technology, more commonly referred to as ‘Fintech’, is the modern day trend for provision of financial services as opposed to the traditional methods prevalent in the industry.

Rapid advances in technology coupled with financial innovation with respect to delivery of financial services and inclusion gives rise to all forms of fintech enabled services such as digital banking, digital app-based lending, crowd funding, e-money or other electronic payment services, robo advice and crypto assets.

In India too, we are witnessing rapid increase in digital app-based lending, prepaid payment instruments and digital payments. The trend shows that even a cash driven economy like India is moving to digitisation wherein cash is merely used as a way to store value as an economic asset rather than to make payments.

“Cash is King, but Digital is Divine.”

- Reserve Bank of India[1]

The Financial Stability Institute (‘FSI’), one of the bodies of the Bank for International Settlement issued a report titled “Policy responses to fintech: a cross country overview”[2] wherein different regulatory responses and policy changes to fintech were analysed after conducting a survey of 31 jurisdictions, which however, did not include India.

In this write up we try to analyse the various approaches taken by regulators of several jurisdictions to respond to the innovative world of fintech along with analysing the corresponding steps taken in the Indian fintech space.

The Conceptual Framework

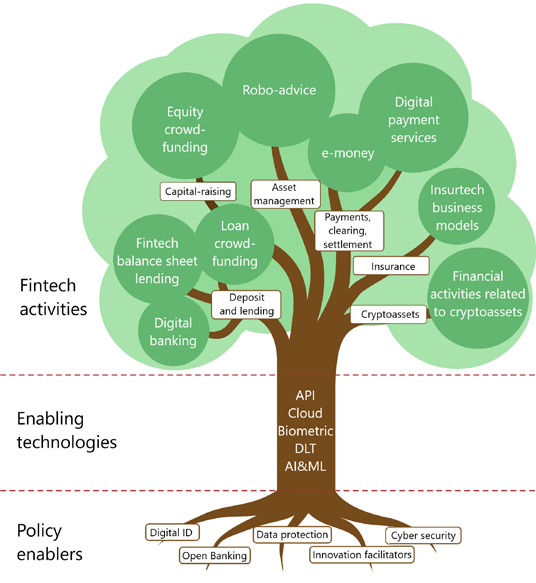

Let us first take a look at the conceptual framework revolving in the fintech environment. Various terminology or taxonomies used in the fintech space, are often used interchangeably across jurisdictions. The report by FSI gives a comprehensive overview of the conceptual framework through a fintech tree model, which characterises the fintech environment in three categories as shown in the figure.

Source: FSI report on Policy responses to fintech: a cross-country overview

Let us now discuss each of the fintech activities in detail along with the regulatory responses in India and across the globe.

Digital Banking –

This refers to normal banking activities delivered through electronic means which is the distinguishing factor from traditional banking activities. With the use of advanced technology, several new entities are being set up as digital banks that deliver deposit taking as well as lending activities through mobile based apps or other electronic modes, thereby eliminating the need for physically approaching a bank branch or even opening a bank branch at all. The idea is to deliver banking services ‘on the go’ with a user friendly interface.

Regulatory responses to digital banking –

The FSI survey reveals that most jurisdictions apply the existing banking laws and regulations to digital banking as well. Applicants with a fintech business model must go through the same licensing process as those applicants with a traditional banking business model.

Only a handful of jurisdictions, namely Hong Kong, SAR and Singapore, have put in place specific licensing regimes for digital banks. In the euro area, specific guidance is issued on how credit institution authorisation requirements would apply to applicants with new fintech business models.

Regulatory framework for digital banking in India –

In India, majority of the digital banking services are offered by traditional banks itself, mainly governed by the Payment and Settlement Systems Act, 2007[1], with RBI being the regulatory body overseeing its implementation. The services include, opening savings accounts online even through apps, facilitating instant transfer of funds through the use of innovative products such as the Unified Payments Interface (UPI), which is governed by the National Payments Corporation of India (NPCI), facilitating the use of virtual cards, prepaid payment instruments (PPI), etc. These services may be provided not only by traditional banks alone, but also by non-bank entities.

Fintech balance sheet lending

Typically refers to lending from the balance sheet and assuming the risk on to the balance sheet of the fintech entity. Investors’ money in the fintech entity is used to lend to customers which shows up as an asset on the balance sheet of the lending entity. This is the idea of balance sheet lending. This idea, when facilitated with technological innovation leads to fintech balance sheet lending.

Regulatory responses to fintech balance sheet lending –

As per the FSI survey, most jurisdictions do not have regulations that are specific to fintech balance sheet lending. In a few jurisdictions, the business of making loans requires a banking licence (eg Austria and Germany). In others, specific licensing regimes exist for non-banks that are in the business of granting loans without taking deposits. Only one of the surveyed jurisdictions has introduced a dedicated licensing regime for fintech balance sheet lending.

Regulatory regime in India –

The new age digital app based lending is rapidly advancing in India. With the regulatory framework for Non-Banking Financial Companies (NBFCs), the fintech balance sheet lending model is possible in India. However, this required a net owned fund of Rs. 2 crores and registration with RBI as an NBFC- Investment and Credit Company.

The digital app based lending model in India works as a partnership between a tech platform entity and an NBFC, wherein the tech platform entity (or fintech entity) manages the working of the app through the use of advanced technology to undertake credit appraisals, while the NBFC assumes the credit risk on its balance sheet by lending to the customers who use the app. We have covered this model in detail in a related write up[2].

Loan & Equity Crowd funding

Crowd funding refers to a platform that connects investors and entrepreneurs (equity crowd funding) and borrowers and lenders (loan crowd funding) through an internet based platform. Under equity crowd funding, the platform connects investors with companies looking to raise capital for their venture, whereas under loan crowd funding, the platform connects a borrower with a lender to match their requirements. The borrower and lender have a direct contract among them, with the platform merely facilitating the transaction.

Regulatory responses to crowd funding –

According to the FSI survey, many surveyed jurisdictions introduced fintech-specific regulations that apply to both loan and equity crowd funding considering the similar risks involved, shown in the table below. Around a third of surveyed jurisdictions have fintech-specific regulations exclusively for equity crowd funding. Only a few jurisdictions have a dedicated licensing regime exclusively for loan crowd funding. Often, crowd funding platforms need to be licensed or registered before they can perform crowd funding activities, and satisfy certain conditions.

Table showing regulatory regimes in various jurisdictions

| Fintech-specific regulations for crowd funding | ||

| Equity Crowd Funding | Equity and Loan Crowd Funding | Loan Crowd Funding |

| Argentina Columbia

Australia Italy Austria Japan Brazil Turkey China United States |

Belgium Peru

Canada Philippines Chile Singapore European Union Spain France Sweden Mexico UAE Netherlands UK |

Australia

Brazil China Italy

|

Source: FSI Survey

Regulatory regime in India

- In case of equity crowd funding –

In 2014, securities market regulator SEBI issued a consultation paper on crowd funding in India[3], which mainly focused on equity crowd funding. However, there was no regulatory framework subsequently issued by SEBI which would govern equity crowd funding in India. At present crowd funding platforms in India have registered themselves as Alternative Investment Funds (AIFs) with SEBI to carry out fund raising activities.

- In case of loan crowd funding –

The scenario for loan crowd funding, is however, already in place. The RBI has issued the Non-Banking Financial Company – Peer to Peer Lending Platform (Reserve Bank) Directions, 2017[4] which govern loan crowd funding platforms. Peer to Peer Lending and loan crowd funding are terms used interchangeably. These platforms are required to maintain a net owned fund of not less than 20 million and get themselves registered with RBI to carry out P2P lending activities.

As per the Directions, the Platform cannot raise deposits or lend on its own or even provide any guarantee or credit enhancement among other restrictions. The idea is that the platform only acts as a facilitator without taking up the risk on its own balance sheet.

Robo- Advice

An algorithm based system that uses technology to offer advice to investors based on certain inputs, with minimal to no human intervention needed is known as robo-advice, which is one of the most popular fintech services among the investment advisory space.

Regulatory responses to robo-advice –

According to the FSI survey, in principle, robo- and traditional advisers receive the same regulatory treatment. Consequently, the majority of surveyed jurisdictions do not have fintech-specific regulations for providers of robo-advice. Around a third of surveyed jurisdictions have published guidance and set supervisory expectations on issues that are unique to robo-advice as compared to traditional financial advice. In the absence of robo-specific regulations, several authorities provide somewhat more general information on existing regulatory requirements.

Regulatory regime in India –

In India, there is no specific regulatory framework for those providing robo-advice. All investment advisers are governed by SEBI under the Investment Advisers Regulations, 2013[5]. Under the regulations every investment adviser would have to get themselves registered with SEBI after fulfilling the eligibility conditions. The SEBI regulations would also apply to those offering robo-advice to investors, as there is no specific restriction on using automated tools by investment advisers.

Digital payment services & e-money

Digital payment services refer to technology enabled electronic payments through different modes. For instance, debit cards, credit cards, internet banking, UPI, mobile wallets, etc. E-money on the other hand would mostly refer to prepaid instruments that facilitate payments electronically or through prepaid cards.

Regulatory responses to digital payment services & e-money –

As per the FSI survey, most surveyed jurisdictions have fintech-specific regulations for digital payment services. Some jurisdictions aim at facilitating the access of non-banks to the payments market. Some jurisdictions have put in place regulatory initiatives to strengthen requirements for non-banks.

Further, most surveyed jurisdictions have a dedicated regulatory framework for e-money services. Non-bank e-money providers are typically restricted from engaging in financial intermediation or other banking activities.

Regulatory regime in India –

The Payment and Settlement Systems Act, 2007 (PSS) of India governs the digital payments and e-money space in India. While several Master Directions are issued by the RBI governing prepaid payment instruments and other payment services, ultimately they draw power from the PSS Act alone. These directions govern both bank and non-bank players in the fintech space.

UPI being a fast mode of virtual payment is however governed by the NPCI which is a body of the RBI.

Other policy measures in India – The regulatory sandbox idea

Both RBI and SEBI have come out with a Regulatory Sandbox (RS) regime[6], wherein fintech companies can test their innovative products under a monitored and controlled environment while obtaining certain regulatory relaxations as the regulator may deem fit. As per RBI, the objective of the RS is to foster responsible innovation in financial services, promote efficiency and bring benefit to consumers. The focus of the RS will be to encourage innovations intended for use in the Indian market in areas where:

- there is absence of governing regulations;

- there is a need to temporarily ease regulations for enabling the proposed innovation;

- the proposed innovation shows promise of easing/effecting delivery of financial services in a significant way.

RBI has already begun with the first cohort[7] of the RS, the theme of which is –

- Mobile payments including feature phone based payment services;

- Offline payment solutions; and

- Contactless payments.

SEBI, however, has only recently issued the proposal of a regulatory sandbox on 17th February, 2020.

Conclusion

Technology has been advancing at a rapid pace, coupled with innovation in the financial services space. This rapid growth however should not be overlooked by regulators across the globe. Thus, there is a need for policy changes and regulatory intervention to simultaneously govern as well as promote fintech activities, as innovation will not wait for regulation.

While most of regulators around the globe have different approaches to governing the fintech space, the regulatory environment should be such that there is sufficient understanding of fintech business models to enable regulation to fit into such models, while also curbing any unethical activities or risks that may arise out of the fintech business.

[1] https://rbidocs.rbi.org.in/rdocs/Publications/PDFs/86706.pdf

[2] http://vinodkothari.com/2019/09/sharing-of-credit-information-to-fintech-companies-implications-of-rbi-bar/

[3] https://www.sebi.gov.in/sebi_data/attachdocs/1403005615257.pdf

[4] https://rbidocs.rbi.org.in/rdocs/notification/PDFs/MDP2PB9A1F7F3BDAC463EAF1EEE48A43F2F6C.PDF

[5] https://www.sebi.gov.in/legal/regulations/jan-2013/sebi-investment-advisers-regulations-2013-last-amended-on-december-08-2016-_34619.html

[6] https://www.rbi.org.in/Scripts/PublicationReportDetails.aspx?UrlPage=&ID=938

https://www.sebi.gov.in/media/press-releases/feb-2020/sebi-board-meeting_46013.html

[7] https://www.rbi.org.in/Scripts/BS_PressReleaseDisplay.aspx?prid=48550

[1] Assessment of the progress of digitisation from cash to electronic – https://www.rbi.org.in/Scripts/PublicationsView.aspx?id=19417