Vinod Kothari (vinod@vinodkothari.com) and Abhirup Ghosh (abhirup@vinodkothari.com)

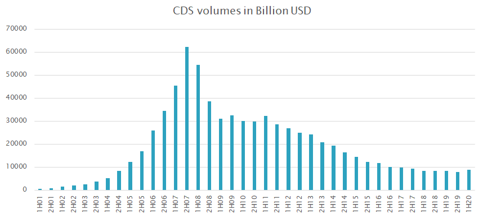

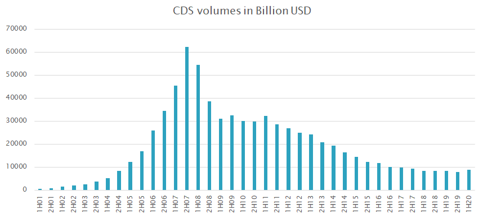

Credit derivatives, an instrument that emerged around 1993–94 and then took the market by storm with volumes nearly doubling every half year, to fall off the cliff during the Global Financial Crisis (GFC), have been a widely used instrument for pricing of credit risk of entities, instruments, and countries. Having earned ignoble epithet as “weapons of mass destruction” from Warren Buffet, they were perceived by many to be such. However, the notional outstanding volume of CDS contracts reached a volume of upwards of USD 9 trillion in June, 2020, the latest data currently available from BIS website.

In India, CDS has been talked about almost every committee or policy recommendation that went into promoting bond markets, and yet, CDSs have been a non-starter ever since the CDS guidelines were first issued in 2013. A credit derivative allows a synthetic trade in a credit asset, and is not merely a hedging device. One of the primary limitations with the 2013 guidelines was that the RBI had taken a very conservative stand and would permit CDS trades only for hedging purposes. The 2021 draft Directions seek to open the market up, on the realisation that much of the activity in the CDS market is not a hedge against what is on the balance sheet, but a synthetic trade on the movement in credit spreads, with no underlying position on the reference bonds or loans.

What is a CDS?

Credit derivatives are derivative contracts that seek to transfer defined credit risks in a credit product or bunch of credit products to the counterparty in the derivative contract. The counterparty to the derivative contract could either be a market participant, or could be the capital market through the process of securitization. The credit product might either be exposure inherent in a credit asset such as a loan, or might be generic credit risk such as bankruptcy risk of an entity. As the risks, and rewards commensurate with the risks, are transferred to the counterparty, the counterparty assumes the position of a virtual or synthetic holder of the credit asset.

The counterparty to a credit derivative product that acquires exposure (called the Protection Seller), from the one who passes on such exposure (called the Protection Buyer), is actually going long on the generalised credit risk of the reference entity, that is, the entity whose debt is being synthetically traded between the Protection Seller and Protection Buyer. The compensation (CDS premium) which the Protection Buyer pays and the Protection Seller receives, is based on the underlying probability of default, occurring during the tenure of the contract, and the expected compensation (settlement amount) that the Protection Seller may be called to pay if the underlying default (credit event) occurs. Thus, this derivative product allows the protection buyer to receive . Thus, the credit derivative trade allows the parties to express on view on (a) whether a credit event is likely to occur with reference to the reference entity during the tenure; and if yes, (b) what will be the depth of the insolvency, on which the compensation amount will depend. As a result, the contract allows people to trade in the credit risk of the entity, without having to trade in a credit asset such as a loan or a bond.

Credit default swaps (CDSs) are the major credit derivative product, which itself falls within the bunch of over-the-counter (OTC) derivatives, the others being interest rate derivatives, exchange rate derivatives, equity derivatives, commodity derivatives, etc. There are, of course, other credit derivative products such as indices trades, basket trades, etc.

Structure of a plain vanilla CDS contract has been illustrated in the following figure:

Fame and shame

Credit derivatives’ claim to fame before the GFC, and shame thereafter, was not merely CDS trading. It was, in fact, synthetic CDOs and their more exotic variations. A synthetic CDO will bunch together several CDS contracts, create layers, and then trade those layers, mostly leaving the manager of the CDO with a fee income and an equity profit. While it could take years to ramp up a book of actual bonds or loans, a synthetic CDS book could be ramped in a matter of hours. In the benign market conditions before the GFC, there were not too many defaults, and therefore, synthetic CDOs and structured finance CDOs would be happily created and sold to investors, with happiness all over. However, since every synthetic CDO would, by definition, be a highly leveraged structure (the lowest tranche bearing the risk of the entire edifice), and multiple sequential layers of such leverage were built by structured finance CDOs, the entire edifice came crumbling during the GFC, as modeling assumptions based on good times of the past were no more true.

RBI hesitatingly allows CDS

The RBI developed cold feet looking at the mess in the global CDS market, and rightly so, and therefore, the RBI has never been bullish on unbridled CDS activity. Hence, the 2013 Guidelines were very guarded and limited permission – only for hedging purposes. Hedging was not something that the Indian bond market needed, as India mostly had highly rated bonds, and the bondholder earning fine spreads will not pay out of these spreads to shell out the risk of a highly rated, mostly held-to-maturity bond investment. Hence, the CDS market never took off.

Nearly every committee that talked about bond markets in India talked about the need to promote CDS. In August 2019[1], the FM announced several reforms that could boost economic growth. One of the proposals was that the MOF, in consultation with the RBI and SEBI will work on the regime for CDS so that it can play an important role in deepening the bond markets in India.

Latest move of the RBI

The Reserve Bank of India (“RBI”) in the Statement of Developmental and Regulatory Policies dated 4th December, 2020[2], expressed its desire to revise the regulatory framework for Credit Default Swaps as a measure to deepen the corporate bonds market, especially the ones issued by the lower rated issuers.

Subsequently, on 16th February, 2021[3], the RBI issued draft Reserve Bank of India (Credit Derivatives) Directions, 2021 (“Draft Directions” or “Proposed Directions”) to replace the Guidelines on Credit Default Swaps (CDS) for Corporate Bonds which was last revised on 7th January, 2013[4] (“2013 Guidelines”).

This write-up attempts to provide a detailed commentary on the Draft Directions, with references to the 2013 Guidelines as and where required, however, before that let us take a note of the key highlights of the proposed revised directions.

Highlights of the Draft Directions

- Participants in a CDS transaction:

The major participants in the proposed transactions:

-

- Market-makers: they are financial institutions

- Non-retail users: they can be protection buyers as well as protection sellers, and purpose of their engagement could be for hedging their risk or otherwise. An exhaustive list of the institutions has been laid down who can be classified as non-retail users

- Retail users: they can be protection buyers as well as protection sellers, however, the purpose of their engaged should be for hedging their risk only. A user who fails to qualify as non-retail user, by default becomes a retail user. Additionally, the Proposed Directions also allow non-retail users to reclassify themselves as retails users.

Persons resident in India are allowed to participate freely, however, persons resident outside India are allowed to participate as per the directions issued by the RBI, which are yet to be issued.

2. Only single-name CDS contracts are permitted:

The Proposed Directions allow single-name CDS contracts only, that is, the CDS contracts should have only one reference entity. Therefore, other forms of the CDS contracts like bucket or portfolio CDS contracts are not allowed.

3. Presence of a reference obligation:

Credit derivatives could either have a reference entity or a reference obligation. The Proposed Directions however envisages the presence of a reference obligation in a CDS contract. This is coming out clearly from the definition of the CDS states that the contract should provide that the protection seller should commit to compensate the other protection buyer for the loss in the value of an underlying debt instrument resulting from a credit event with respect to a reference entity, for a premium.

4. Eligible reference obligations:

The reference obligations include money market instruments like CPs, CDs, and NCDs with maturity upto 1-year, rated rupee denominated (listed and unlisted) corporate bonds, and unrated corporate bonds issued by infrastructure companies. In this regard, it is pertinent to note that the

5. Structured finance transactions:

Neither can credit derivatives be embedded in structured finance transactions like, synthetic securitisations, nor can structured finance instruments like, ABS, MBS, credit enhanced bonds, convertible bonds etc., be reference obligations for CDS contracts.

Commentary on some of the Key Provisions of the Draft Directions

Applicability

The Proposed Directions will apply on all forms of the credit derivatives transactions irrespective of whether they are undertaken in the OTC markets and or on recognised stock exchanges in India.

Definitions

5. Cash settlement:

Relevant extracts:

(i) Cash settlement of CDS means a settlement process in which the protection seller pays to the protection buyer, an amount equivalent to the loss in value of the reference obligation.

Our comments:

The Proposed Directions allow cash settlement of the CDS, where the protection seller pays only the actual loss in the reference obligation to the protection buyer. There are usually two ways of computing the settlement amount in case of cash settlement – first, based on the actual value of the loss arising from the reference obligation, and second, based on a fixed default rate which is agreed between the parties to the contract at its very inception.

To understand the second situation, let us take an example of a contract where the protection seller agrees to compensate the losses of the protection buyer arising from a reference obligation. Say, the seller agrees to compensate the buyer assuming a 10% default in the buyer’s exposure in a debt instrument on happening of a credit event. In this case, if the credit event happens, the seller will compensate the buyer assuming a 10% default rate, irrespective of the whether losses are more or less than 10%.

However, in the first case, settlement amount would work out based on the assessment of actual losses arising due to happening of the credit event.

Apparently, the definition of cash settlement seems to include only the first case, as it refers to an amount equivalent to the loss in value of the reference obligation.

6. Credit default swaps

Relevant extracts:

(iii) Credit Default Swap (CDS) means a credit derivative contract in which one counterparty (protection seller) commits to compensate the other counterparty (protection buyer) for the loss in the value of an underlying debt instrument resulting from a credit event with respect to a reference entity and in return, the protection buyer makes periodic payments (premium) to the protection seller until the maturity of the contract or the credit event, whichever is earlier.

Our comments:

CDS contracts can be drawn with reference to a particular entity or to a particular obligation of an entity. In the former case, the reference is on all the obligations of the reference entity, whereas in the latter case, the reference is on a particular debt obligation of the reference entity – which could be a loan or a bond.

However, the definition of CDS in the Proposed Directions states the contract should be structured in a manner where the protection seller commits to compensate the protection buyer for the loss in the value of an underlying debt instrument. Therefore, the exposure has to be taken on a particular debt obligation, and it cannot be generally on the reference entity.

7. Credit event:

Relevant extracts:

(iv) Credit event means a pre-defined event related to a negative change/ deterioration in the credit worthiness of the reference entity underlying a credit derivative contract, which triggers a settlement under the contract.

Our comments:

In the simplest form of a credit derivative contract, credit event is a contingent event on happening of which the protection buyer could incur a credit loss, and for which it seeks protection from the protection seller. The definition used in the Proposed Directions is a very generalised one. As per ISDA, the three most credit events include –

- Filing for bankruptcy of the issuer of the debt instrument;

- Default in payment by the issuer;

- Restructuring of the terms of the debt instrument with an objective to extend a credit relief to the issuer, who is otherwise under a financial distress.

8.Deliverable obligation

Relevant extracts:

(v) Deliverable obligation means a debt instrument issued by the reference entity that the protection buyer can deliver to the protection seller in a physically settled CDS contract, in case of occurrence of a credit event. The deliverable obligation may or may not be the same as the reference obligation.

Our comments:

Refer discussion on physical settlement below.

In case of physical settlements, the question arises, what is the asset that protection buyers may deliver? As discussed under physical settlement, protection buyers may exactly hold the reference asset. A default on this asset would also imply a default on other parallel obligations of the obligor: therefore, market practices allow parallel assets to be delivered to protection sellers. Essentially, a protection buyer may select out of a range of obligations of the reference entity, and logically, will select the one that is the cheapest to deliver. To ensure that the asset delivered is not completely junk, certain filters are covered in the documents, and the deliverable asset must conform to those filters. In particular, these limitations are quite relevant when the reference entity has not really defaulted on its obligations, but only undergone a restructuring credit event.

9. Physical settlement

Relevant extracts:

(xv) Physical settlement of CDS means a settlement process in which the protection buyer transfers any of the eligible deliverable obligations to the protection seller against the receipt of notional/face value of the deliverable obligation.

Our comments:

We discussed earlier that one of the ways of settling a CDS contract is the cash settlement. The other way of settling a CDS contract is the physical settlement. In case of physical settlement, protection buyers physically deliver; that is, transfer an asset of the reference entity and get paid the par value of the delivered asset, limited, of course, to the notional value of the transaction. The concept of deliverable obligation in a credit derivative is critical, as the derivative is not necessarily connected with a particular loan or bond. Being a transaction linked with generic default risk, protection buyers may deliver any of the defaulted obligations of the reference entity.

In case of physical settlement, there is a transfer of the deliverable reference obligation to protection sellers upon events of default, and thereafter, the recovery of the defaulted asset is done by protection sellers, with the hope that they might be able to cover some of their losses if the recovered amount exceeds the market value as might have been estimated in the case of a cash settlement. This expectation is quite logical since the quotes in case of cash settlement are made by potential buyers of defaulted assets, who also hope to make a profit in buying the defaulted asset. Physical settlement is more common where the counterparty is a bank or financial intermediary who can hold and take the defaulted asset through the bankruptcy process, or resolve the defaulted asset.

10. Reference entity:

Relevant extracts:

(xvi) Reference entity means a legal entity, against whose credit risk, a credit derivative contract is entered into.

Our comments:

As may be noted later on in the writeup, reference entity in the context of the Proposed Directions refers to a legal entity resident in India.

11. Reference obligation

Relevant extracts:

(xvii) Reference obligation means a debt instrument issued by the reference entity and specified in a CDS contract for the purpose of valuation of the contract and for determining the cash settlement value or the deliverable obligation in case of occurrence of a credit event.

Our comments:

Reference obligation is the underlying debt instrument, based on which the contract is drawn. In practice, this obligation could be loan, or a bond of the obligor. However, the Proposed Directions refer to certain money market instruments and corporate bonds. Discussed later.

12. Single-name CDS

Relevant extracts:

(xix) Single-name CDS means a CDS contract in which the underlying is a single reference entity.

Our comments:

Usually, CDS could be created with reference to either a single obligation, or obligations from a single reference entity, or a portfolio of obligations arising from different reference entities. The Proposed Directions completely rules out portfolio derivatives, and allows CDS contracts with reference to a single entity only.

Eligible participants

Relevant extracts:

- Eligible participants

The following persons shall be eligible to participate in credit derivatives market:

(i) A person resident in India;

(ii) A non-resident, to the extent specified in these Directions.

Our comments:

Any person resident in India is eligible to participate in the credit derivatives market. Even retail investors have been allowed to be a part of this, however, restrictions have been imposed on specific classes of users concerning the purpose of their participation.

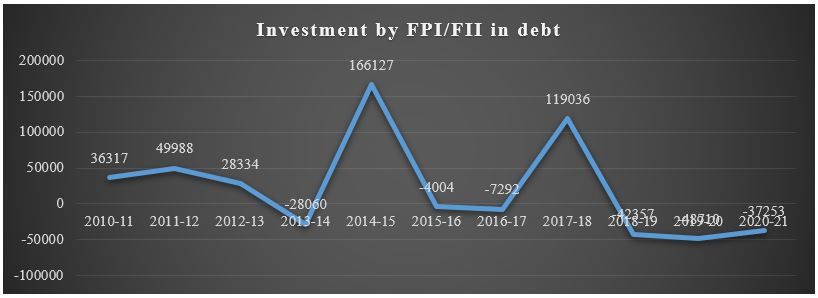

Non-resident users, like FPIs, have also been allowed to participate on a restricted basis, however, specifics of their limitations will come by way of specific directions which will be issued by the RBI in due course.

Permitted products

- Permitted products in OTC market

(i) Market-makers and users may undertake transactions in single-name CDS contracts.

(ii) Market-makers and users shall not deal in any structured financial product with a credit derivative as one of the components or as an underlying.

As already discussed earlier, only single-name CDS contracts are allowed, bucket or portfolio CDS contracts are not permitted. One of the reasons for this could be that RBI might like to test the market before allowing the users to write contracts on exposures on multiple obligors.

Clause (ii) prohibits the use of credit derivatives in the structure finance products. Synthetic securitisation is one of the products that use embeds a credit default swap in the securitisation transaction. Presently, the Securitisation Guidelines[5] has put a bar on synthetic securitisation, in fact, the draft Guidelines on Securitisation, issued by the RBI in 2019[6], also retained the bar on synthetic securitisation.

Vinod Kothari, in his article Securitisation – Should India be moving to the next stage of development?[7], stated:

It is notable that a synthetic securitisation uses CDS to shift a tranched risk of a pool of assets into the capital markets by embedding the same into securities, without giving any funding to the originator. Synthetic structures are intended mainly at capital relief, both economic capital as well as regulatory capital.

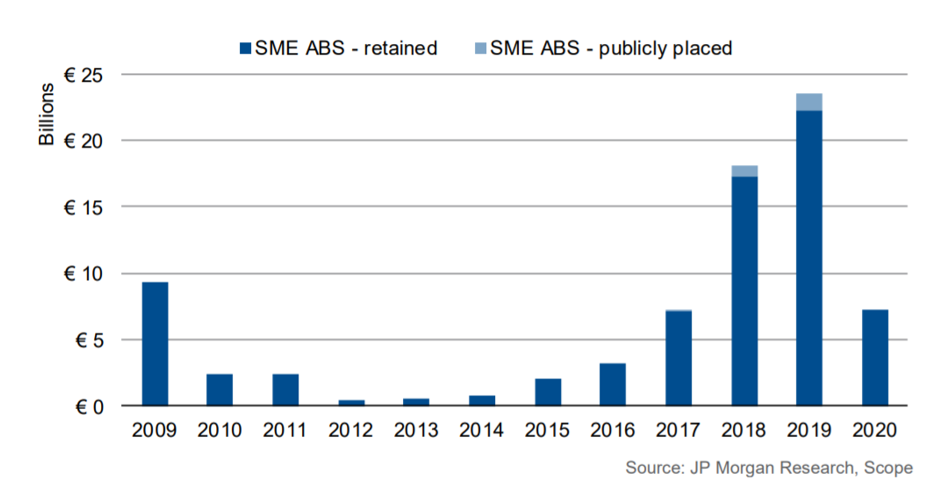

Synthetic securitisation may come in handy for Indian banks to gain capital relief. Synthetic securitisation structures are seen by many to have made a comeback after the GFC. In fact, the European Banking Authority has launched a consultation process for laying down a STS framework for synthetic securitisations as well[8]. A Discussion Paper of EBA says: “The 2008 financial crisis marked a crash of the securitisation market, after which, also due to stigma attached to the synthetic segment, the securitisation market has gradually emerged in particular in the traditional (and retained) form. With respect to synthetic securitisation following a few years of subdued issuance, the synthetic market has been recovering in the recent years, with both the number and volume of transactions steadily increasing. Based on the data collection conducted by IACPM, altogether 244 balance sheet synthetic securitisations have been issued since 2008 up until end 2018. In 2018, 49 transactions have been initiated with a total volume of 105 billion EUR.”[9]

In the USA as well, credit risk transfer structure has been used by Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae vide instruments labelled as Structured Agency Credit Risk (STACR) and Connecticut Avenue Securities™ (CAS) bonds. Reportedly, the total volume of risk transferred using these instruments, for traditional single family dwelling units, has crossed USD 2.77 trillion by end of 2018[10].

There may be merit in introducing balance sheet synthetic securitisations by banks and NBFCs. To begin with, high quality portfolios of home loans, consumer loans or other diversified retail pools may be the reference pools for these transactions. Gradually, as the market matures, further asset classes such as corporate loans may be tried.

Synthetic securitisations were frowned upon by financial regulators across the globe after the GFC, however, as may have been noticed in the extracts quoted above, several developed jurisdictions now allow synthetic securitisation, with the required level of precautions added to the regulatory framework dealing with it.

Reference entities and obligations for CDS

Relevant extracts:

- Reference Entities and Obligations for CDS

(i) The reference entity in a CDS contract shall be a resident legal entity who is eligible to issue any of the debt instruments mentioned under paragraph 5(ii).

(ii) The following debt instruments shall be eligible to be a reference / deliverable obligation in a CDS contract:

- Commercial Papers, Certificates of Deposit and Non-Convertible Debentures of original maturity upto one year;

- Rated INR corporate bonds (listed and unlisted); and

- Unrated INR bonds issued by the Special Purpose Vehicles set up by infrastructure companies.

(iii) The reference/deliverable obligations shall be in dematerialised form only.

(iv) Asset-backed securities/mortgage-backed securities and structured obligations such as credit enhanced/guaranteed bonds, convertible bonds, bonds with call/put options etc. shall not be permitted as reference and deliverable obligations.

Our comments:

As per Clause 5(i), only resident legal entities can be reference entities for the purpose of CDS contracts, however, the Proposed Directions are silent on the meaning of the term resident legal entity. One could argue that entities which are registered in India should be treated as resident legal entities, however, a clarification in this regard shall remove the ambiguities.

Clause (ii) allows the use of the following instruments as a reference obligations:

- Money market instruments like CPs, CDs and short-term NCDs

- Rated Rupee-denominated corporate bonds, both listed and unlisted

- Unrated rupee-denominated corporated bonds issued by infrastructure companies.

The 2013 Guidelines also provided for similar set of instruments. However, it is pertinent to note that the Proposed Directions provide for an express bar on usage of the following structured products as reference obligations:

- Asset backed securities

- Mortgage backed securities

- Credit enhanced or guranateed bonds

- Convertible bonds

- Bonds with embedded call/ put options

Loans continue to be ineligible for use as reference obligation.

Market makers and users

Relevant extracts:

6.1 Market-makers

(i) The following entities shall be eligible to act as market-makers in credit derivatives:

- Scheduled Commercial Banks (SCBs), except Small Finance Banks, Payment Banks, Local Area Banks and Regional Rural Banks;

- Non-Bank Financial Companies (NBFCs), including Housing Finance Companies (HFCs), with a minimum net owned funds of ₹500 crore as per the latest audited balance sheet and subject to specific approval of the Department of Regulation (DoR), Reserve Bank.

- Standalone Primary Dealers (SPDs) with a minimum net owned funds of ₹500 crore as per the latest audited balance sheet and subject to specific approval of the Department of Regulation (DoR), Reserve Bank.

- Exim Bank, National Bank of Agriculture and Rural Development (NABARD), National Housing Bank (NHB) and Small Industries Development Bank of India (SIDBI).

(ii) In case the net owned funds of an NBFC, an HFC or an SPD as per the latest audited balance sheet fall below the aforesaid threshold subsequent to the receipt of approval for acting as a market-maker, it shall cease to act as a market-maker. The NBFC, HFC or SPD shall continue to meet all its obligations under existing contracts till the maturity of such contracts.

(iii) Market-makers shall be allowed to buy protection without having the underlying debt instrument.

(iv) At least one of the parties to a CDS transaction shall be a market-maker or a central counter party authorised by the Reserve Bank as an approved counterparty for CDS transactions.

Our comments:

When compared to the 2013 Guidelines, the only addition to list of entities that are eligible to act as market makers is housing finance companies. The net-worth requirements for NBFCs and SPDs remain the same as that under 2013 Guidelines. However, here it is pertinent to note that while the banks are not required to obtain any specific approval from the RBI, NBFCs and SPDs will have to obtain specific approval from the Department of Regulation. The RBI may reconsider this position and remove the requirement of obtaining special approval for the NBFCs and SPDs and put them in a level playing field with the banks.

Relevant extracts:

6.2 User Classification Framework

(i) For the purpose of offering credit derivative contracts to a user, market-maker shall classify the user either as a retail user or as a non-retail user.

(ii) The following users shall be eligible to be classified as non-retail users:

- Insurance Companies regulated by Insurance Regulatory and Development Authority of India (IRDAI);

- Pension Funds regulated by Pension Fund Regulatory and Development Authority (PFRDA);

- Mutual Funds regulated by Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI);

- Alternate Investment Funds regulated by Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI);

- SPDs with a minimum net owned funds of ₹500 crore as per the latest audited balance sheet;

- NBFCs, including HFCs, with a minimum net owned funds of ₹500 crore as per the latest audited balance sheet;

- Resident companies with a minimum net worth of ₹500 crore as per the latest audited balance sheet; and

- Foreign Portfolio Investors (FPIs) registered with SEBI.

(iii) Any user who is not eligible to be classified as a non-retail user shall be classified as a retail user.

(iv) Any user who is otherwise eligible to be classified as a non-retail user shall have the option to get classified as a retail user.

(v) Retail users shall be allowed to undertake transactions in permitted credit derivatives for hedging their underlying credit risk.

(vi) Non-retail users shall be allowed to undertake transactions in credit derivatives for both hedging and other purposes.

Our comments:

As brought out earlier under the highlights section, there can be two types of users – non retail and retail users. Financial institutions, resident corporates with networth of Rs. 500 crores or above, and FPIs can become non-retail users. The non-retail users can participate in these contracts either for hedging their credit risk or any other purposes.

On the other hand, anyone who is not eligible to become a non-retail user, by default becomes a retail user. Additionally, non-retail users have been given an option to reclassify themselves as retail issuers should they want. Retail users are allowed to undertake these transactions only for the hedging their credit risk.

The provisions under the Proposed Directions differ significantly from that under the 2013 Guidelines which allowed only financial institutions and FIIs to participate as users. Further, neither did the Guidelines differentiate between retail and non-retail users, nor did it allow the use of CDS for other than hedging purposes.

The classification between retail and non retail users is welcome move where they have not put any restriction on the more serious non-retail users, who can use these even for speculative purposes, apart from hedging. This could increase the liquidity of the instruments, therefore, deepening the market.

Operations and standardisations

Relevant extracts:

7.1 Buying, Unwinding and Settlement

(i) Market-makers and users shall not enter into CDS transactions if the counterparty is a related party or where the reference entity is a related party to either of the contracting parties.

(ii) Market-makers and users shall not buy/sell protection on reference entities if there are regulatory restrictions on assuming similar exposures in the cash market or in violation of any other regulatory restriction, as may be applicable.

(iii) Market-makers shall ensure that all CDS transactions by retail users are undertaken for the purpose of hedging i.e. the retail users buying protection:

- shall have exposure to any of the debt instruments mentioned under paragraph 5(ii) and issued by the reference entity;

- shall not buy CDS for amounts higher than the face value of the underlying debt instrument held by them; and

- shall not buy CDS with tenor later than the maturity of the underlying debt instrument held by them or the standard CDS maturity date immediately after the maturity of the underlying debt instrument.

To ensure this, market-makers may call for any relevant information/documents from the retail user, who, in turn, shall be obliged to provide such information.

(iv) Retail users shall exit their CDS position within one month from the date they cease to have underlying exposure.

(v) Market participants can exit their CDS contract by unwinding the contract with the original counterparty or assigning the contract to any other eligible market participant.

(vi) Market participants shall settle CDS contracts bilaterally or through any clearing arrangement approved by the Reserve Bank.

(vii) CDS contracts shall be denominated and settled in Indian Rupees.

(viii) CDS contracts can be cash settled or physically settled. However, CDS contracts involving retail users shall be mandatorily physically settled.

(ix) The reference price for cash settlement shall be determined in accordance with the procedure determined by the Credit Derivatives Determinations Committee or auction conducted by the Credit Derivatives Determinations Committee, as specified under paragraph 8 of these Directions.

Our comments:

The Proposed Directions imposes restrictions on the users to enter into contracts involving their related parties.

Further, as noted earlier, contracts entered into by the retail users must be for the purpose of the hedging credit risks only, in addition to it there are some other restrictions with respect to the tenor and amount of the protection. However, the onus to ensure that these conditions are met with have been imposed on the market makers. This leads to an additional compliance on the part of the market makers.

In terms of settlement, the Proposed Directions allow both cash and physical settlement, however, for retail users only physical settlement is allowed.

Further, the Proposed Directions also provide for the manner of exiting a CDS contract. In practice, there are three ways of settling a credit derivative contract – first, by settlement in cash or physically, second, by entering into a matching contract with a third party, therefore knocking off the contract in the hands of the protection buyer, and third, by assigning the contract to third parties. The Proposed Directions allow all of these.

Relevant extracts:

7.2 Standardisation

(i) Fixed Income Money Market and Derivatives Association of India (FIMMDA), in consultation with market participants and based on international best practices, shall devise standard master agreement/s for the Indian CDS market which shall, inter-alia, include credit event definitions and settlement procedures.

(ii) FIMMDA shall, at the minimum, publish the following trading conventions for CDS contracts:

- Standard maturity and premium payment dates;

- Standard premiums;

- Upfront fee calculation methodology;

- Accrual payment for full first premium;

- Quoting conventions; and

- Lookback period for credit events.

Our comments:

FIMMDA has been authorised to standardise the documents, and conventions for CDS contracts. World-over standard CDS products are prevalent with standard maturity dates, coupon payments, rates. Standardisation of key terms of a credit derivative contract transform the product from bespoke bilateral transactions to standard marketable products.

Some of the prevalent conventions used internationally are the Standard North Amercian Corporate Convention (SNAC) or the Standard European Corporate (SEC) Convention. The aim of both these conventions is to standardize the trading mechanics of credit default swaps (the SNAC for North American corporate names and the SEC for European corporate names) and facilitate trading through a central clearing counterparty, as well as to reduce uncertainty associated with credit events. This is because in order to make trades completely fungible (i.e., so they have the quality of being capable of exchange or interchange), all trading conventions have to be fully standardized.

Both the conventions have the following trading mechanics:

- They have a fixed coupon and an upfront fee.

- The first coupon of a CDS accumulates from the date of the last coupon, regardless of the trade date.

- The quoted spread for a given maturity is assumed to be a flat spread, rather than representing a point in the term structure.

References from the aforesaid conventions could be drawn while standardisation of the CDS conventions for the Indian market.

Prudential norms, accounting and capital requirements

Relevant extracts:

- Prudential norms, accounting and capital requirements

Market participants shall follow the applicable prudential norms and capital adequacy requirements for credit derivatives issued by their respective regulators. Credit derivative transactions shall be accounted for as per the applicable accounting standards prescribed by The Institute of Chartered Accountants of India (ICAI) or other standard setting organisations or as specified by the respective regulators of participants.

Our comments:

The market participants shall have to follow prudential norms and capital adequacy requirements for credit derivatives issued by the sectoral regulators. For NBFCs, for credit protection purchased, for corporate bonds held in current category – capital charge has to be maintained on 20% of the exposure, whereas for corporate bonds held in permanent category, and where there is no mismatch between the hedged bond and the CDS, full capital protection is allowed. The exposure shall stand replaced by exposure on the protection seller, and attract risk weights at 100%.

Similar provisions apply for banks, however, for bonds held in the permanent category, where there is no mismatch between the hedged bonds and CDS, the capital charge on the corporate bonds is nil, whereas, the capital charge on the exposure on protection sellers is maintained at 20% risk weight.

In terms of accounting, for NBFCs and HFCs, Ind AS 109 will have to be followed. Banks however will have to rely on ICAI’s Guidance Notes, if any, to do the accounting.

Our other resources on the topic:

- Our dedicated page on Credit Derivatives: http://vinodkothari.com/cdhome/

- Our articles on Credit Derivatives: http://vinodkothari.com/creart/

- Our book, Credit Derivatives & Structured Credit Trading, by Vinod Kothari – http://vinodkothari.com/crebook/

[1] https://static.pib.gov.in/WriteReadData/userfiles/ASss%2023%20August.pdf

[2] https://www.rbi.org.in/Scripts/BS_PressReleaseDisplay.aspx?prid=50748

[3] https://www.rbi.org.in/Scripts/BS_PressReleaseDisplay.aspx?prid=51138

[4] https://www.rbi.org.in/scripts/NotificationUser.aspx?Id=7793&Mode=0

[5] https://rbidocs.rbi.org.in/rdocs/notification/PDFs/C170RG21082012.pdf

[6]https://rbidocs.rbi.org.in/rdocs/PublicationReport/Pdfs/STANDARDASSETS1600647F054448CB8CCEC47F8888FC78.PDF

[7] http://vinodkothari.com/2020/01/securitisation-india-and-global/

[8] https://eba.europa.eu/eba-consults-on-its-proposals-to-create-a-sts-framework-for-synthetic-securitisation

[9] https://eba.europa.eu/file/113260/download?token=RpXCSVe2,

[10] Based on https://www.fhfa.gov/AboutUs/Reports/ReportDocuments/CRT-Progress-Report-4Q18.pdf

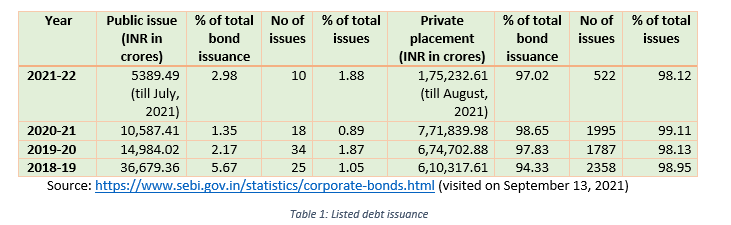

Given the details of bonds issuance and present outstanding indicated above, there would be several entities that would be regarded as an HVD entity. In view of SEBI’s requirements under Large Corporate Borrower framework, entities with any of its securities listed, having an outstanding long term borrowing of Rs. 100 crores or above and with credit rating of ‘AA and above’[4], will have to mandatorily raise 25% of its incremental borrowing by ways of issuance of debt securities or pay monetary penalty/fine of 0.2% of the shortfall in the borrowed amount at the end of second year of applicability[5].

Given the details of bonds issuance and present outstanding indicated above, there would be several entities that would be regarded as an HVD entity. In view of SEBI’s requirements under Large Corporate Borrower framework, entities with any of its securities listed, having an outstanding long term borrowing of Rs. 100 crores or above and with credit rating of ‘AA and above’[4], will have to mandatorily raise 25% of its incremental borrowing by ways of issuance of debt securities or pay monetary penalty/fine of 0.2% of the shortfall in the borrowed amount at the end of second year of applicability[5].