Resolution Plans – A Non returning visa to the resolution land

Anushka Vohra | Deputy Manager (corplaw@vinodkothari.com)

On September 13, 2021, in the matter of Ebix Singapore Private Limited v. Committee of Creditors of Educomp Solutions Limited[1], the Apex Court ruled that a Resolution Plan, once submitted with the Adjudicating Authority (“AA”) for approval, cannot be subsequently withdrawn at the behest of the Resolution Applicant. While this question of withdrawal of resolution plans has been around for quite some time, especially due to the COVID disruption, the Hon’ble Supreme Court has now given the final word of law.

The aforesaid order came when the RA filed an application for withdrawal of the Resolution Plan on the grounds that due to prolonged delay in getting the approval of the Resolution Plan from the AA, the commercial viability of the CD has been eroded. While the request was allowed in view of the other material change in facts (discussed below), the same was declined in an appeal filed by the CoC before the AA. The matter finally came before the Apex Court for consideration; however, the Apex Court’s decision was also aligned with the Appellate Tribunal – the Hon’ble Supreme Court directed that to ensure maintenance of timelines stipulated under the Code, a resolution plan once submitted before the AA cannot be withdrawn at the choice of the RA.

With the said verdict now in place, the questions which arise from the present order are that whether a RA should be allowed to withdraw a Resolution Plan, due to time being taken in its approval, for no fault of his ? And that, should an unwilling RA be still afflicted with the onus to implement the Resolution Plan?

In this write-up, we shall delve into the above issues in light of the order of the Hon’ble Supreme Court, and also discuss various ramifications that could follow.

Case in hand

In this case, Educomp Solutions Limited (“Corporate Debtor” / “CD”) filed an application for initiating Corporate Insolvency Resolution Process (CIRP) against itself under section 10 of the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Act, 2016 (“ Code”), the same was admitted. As further development to the CIRP the Resolution Plan submitted by Ebix Singapore Private Limited (‘Resolution Applicant’/ ‘RA’) was approved by the CoC with requisite majority, and was filed with the NCLT for approval.

Section 31 of the Code provides that the AA shall, before according its approval on the Resolution Plan, be satisfied that the Resolution Plan meets the requirements as referred to in 30(2). However, pending the approval of the Resolution Plan by the AA, some members of the CoC filed an application with the AA for initiating investigation into the financial affairs of the CD. NCLT dismissed their applications and called upon the Resolution Professional to conduct a meeting of CoC for discussion on the subject matter. In the meantime, MCA directed the Serious Fraud Investigation Office (SFIO) to conduct an investigation into the affairs of the CD.

The gamut of investigations and material change in the facts and circumstances of the CD, caused the RA to make an appeal to the NCLT for modifying / withdrawing the Resolution Plan. The same was allowed by the AA, however on an appeal made to the NCLAT by the CoC, the order of NCLT was reversed. Being aggrieved, the RA preferred an appeal to the Hon’ble Supreme Court, challenging the order of the NCLAT.

Can a Resolution Plan approved by the CoC be withdrawn ?

As far as the Code is concerned, there is no explicit provision for allowing withdrawal of the Resolution Plan. The provisions relating to withdrawal are only for the applications filed u/s 7, 9 and 10 for initiation of CIRP – no provisions have been expressly made for withdrawal of Resolution Plans.

In the present case, the Hon’ble Supreme Court held that enabling withdrawals or modifications of the Resolution Plan, once it has been submitted to the AA, would create another tier of negotiations which will be wholly unregulated by the Code and would either result in a down-graded resolution amount of the Corporate Debtor and/or a delayed liquidation with depreciated assets which frustrates the very core of IBC.

The question of withdrawal of resolution plans has come up several times, some instances have been quoted here. In the matter of Kundan Care Products Limited[2], the Hon’ble NCLAT allowed modification of the Resolution Plan after its submission to the AA, by invoking A. 142 of the Indian Constitution. An excerpt of the Kundan case, as mentioned in this appeal is as under :

“In the case of Kundan Care, since both, the Resolution Applicant and the CoC, have requested for modification of the Resolution Plan because of the uncertainty over the PPA, cleared by the ruling of this Court in Gujarat Urja (supra), a one-time relief under Article 142 of the Constitution is provided.”

In the case of Seroco Lighting Industries Private Limited[3], the Resolution Plan was approved by the NCLT. However, due to material changes in the economic condition of the CD, the Resolution Applicant approached the NCLT for permitting it to revise the Resolution Plan. NCLT rejected the plea of the Resolution Applicant, against the NCLTs judgement, appeal was filed by Seroco to NCLAT, NCLAT upheld the judgement of NCLT stating that “Seroco being a company formed by its former employees (who would have been aware of its financial condition) and also being the sole Resolution Applicant, the modification / withdrawal shall not be permitted.”

Circumstances where withdrawal is allowed – expressing the intent of Law

Time bound process is one of the objectives and the very essence of the Code. From the above judicial pronouncements, we infer that a resolution plan once filed with the AA for approval cannot be subsequently withdrawn, not even on account of significant changes in the financial and economic conditions of a corporate debtor since the time the resolution plan was prepared. The intent of law is that any modification in the plan or its withdrawal can only be justified in case of mutual consensus between the CoC and the RA.

Should withdrawal be permitted? – Author’s analysis

With the order of the Hon’ble Supreme Court, it is clear that once a successful resolution applicant proposes to revive a CD, there is no exit under the Code except when he fails to implement the Resolution Plan within the timelines as stipulated in the Resolution Plan. While humbly disagreeing with the same, we believe that allowing no withdrawal of a resolution plan is no less than weighing down an unwilling RA with the obligation to execute a resolution plan.

As mentioned above, section 31 of the Code mandates the AA to assess the Resolution Plan prior to granting its approval. If at the outset, the RA states that it can no longer pull off the Resolution Plan, the Plan ought to be rejected. The pandemic has hit the entire economy, if the economic conditions of the CD has changed over time, it is very likely that the financial position of the RA might also have taken a downturn.An RA is bestowed with the responsibility of reviving a CD, which is in financial duress. A slump in the entire market would make it difficult for the RA to meet his obligations under the Resolution Plan. What if the financial position of the RA is still intact, but time has destroyed the ‘crown jewels’ of the CD. Why should RAs be the scapegoat for the time lag ?

The Code aims to resolve the insolvency resolution process in a time bound manner, thereby avoiding depletion in the value of the CD. The Standing Committee on Finance (2020-21), Ministry of Corporate Affairs, in its report[4] has stated that there has been delay in the resolution process with more than 71% cases pending for more than 180 days and this is a clear deviation from the original objectives of the Code.

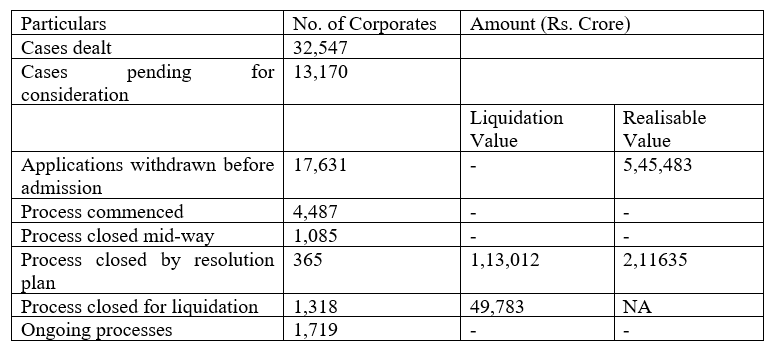

Source: Report of Standing Committee on Finance (2020-21)

We have been reiterating that the CIRP is the last resort for saving a CD from corporate death by way of liquidation. The principles of a successful resolution plan as evidenced in the case of Binani Industries Limited v. Bank of Baroda was that the CIRP is not a sale, recovery or liquidation and that the Code allows liquidation only on failure of CIRP. Referring to section 33 of the Code, it states that where a plan has been contravened, the AA shall pass an order for liquidation. Thus, for failure in implementation of the plan or in case of contravention of the same, the Code refers to liquidation as an alternative to failed CIRP.

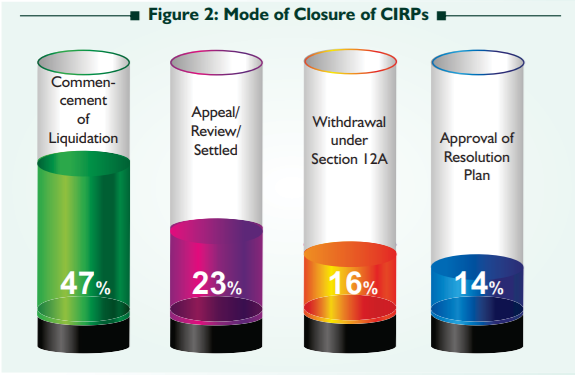

As per the quarterly report ending June, 2021 released by IBBI, the data shows that in 47% of the cases liquidation was commenced and in 14% cases CIRP was successful.

Source: Quarterly Newsletter {IBBI}

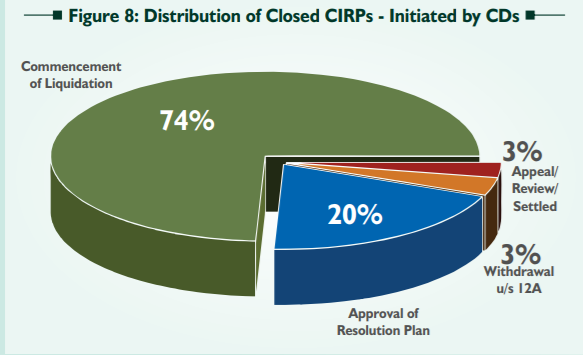

The data also shows that in cases where the CDs themselves initiated CIRP, only 20% of the cases resulted in successful CIRP, whereas 74% cases went into liquidation.

Source: Quarterly Newsletter {IBBI}

The above statistics clearly shows that time lag is anyway pushing the distressed CDs into liquidation. The enhancement of time period to maximum 330 days, in case of investigations is also not solving the purpose. Also, delays are not always owed to the investigations or cross appeals but the period of Covid has led to a stagnant economy with the NCLT benches not working at their full capacity, thereby delay being caused in hearing of matters.

Considering how circumstantial the delays could be, why should the RAs bear the brunt ? Why does not the thought of commencing liquidation prevail over the thought of compelling an unwilling RA to carry out the Resolution Plan. The time lag in approval of Resolution Plans depletes the value of the CD hence it can be rightly said that if the liquidation is commenced at the right time, the assets of the CD could appropriately be sold without further depletion in the assets.

Remedies to the RA

The Resolution Plans are prepared in accordance with the Information Memorandum (IM) as furnished to the prospective RAs. The IM is prepared on a certain date and the same facts cannot hold true until an indefinite time. The RAs submit their proposals on the basis of the same facts. Also, the position of a CD is bound to change and any negative change would affect the RA who has agreed to resurrect the CD on the basis of such facts. Although the RA assumes the risk they might face in implementing the Resolution Plan, however, they cannot be burdened with the baggage of change in circumstances for an infinite time.

With this order of the Hon’ble Supreme Court, the RAs are left with little or no remedy but to implement the plan. The RAs should assume greater quantum of risk, along with the financial risk, they should also take into account the possibility of investigations being initiated in a particular case, thereby increasing the time in approval of plans. Appropriate cushioning against such risks should be assumed at the initial stage.

Also, most importantly, the Resolution Plans should provide a timeline of its validity and should provide that it is not valid for an indefinite period. Further, there should be an appropriate provision of withdrawal stating that the resolution applicant would be at liberty to withdraw the resolution plan in the event that there is any change in the information provided in the IM or new information is available, which constitutes a ‘material adverse’ change.

Failure to implement the Plan

Now since the final verdict is in place, an unwilling resolution applicant cannot step back. Given the case, there is a possibility that a plan fails to get implemented at a later stage, probably due to the reasons cited by a resolution applicant, as grounds for withdrawal. It is therefore pertinent to understand the consequences which a resolution applicant and a corporate debtor might face as an aftermath of unsuccessful implementation of a resolution plan.

The failure of implementation of a resolution plan is a sign that the CD cannot be revived and that knocking the doors of AA for order of liquidation, seems to be the only option left. Section 33(3) of the Code states that, where the resolution plan approved by the Adjudicating Authority is contravened by the concerned corporate debtor, any person other than the corporate debtor, whose interests are prejudicially affected by such contravention, may make an application to the Adjudicating Authority for a liquidation order as referred to in sub-clauses (i), (ii) and (iii) of clause (b) of sub-section (1).

In the case of Yavar Dhala v. JM Financial Asset Reconstruction Company Ltd[5] & Ors., Hon’ble NCLAT held that ‘on failure of the resolution applicant to implement the terms of the resolution plan, liquidation has to follow.’ It cannot be denied that by this time, the value of the assets of the corporate debtor would have been depleted, being the liquidation value reduced to infinitesimal. Had the liquidation order been passed at an earlier stage, given the unwillingness of the resolution applicant, at least the corporate debtor would have some commercial value to be effectively distributed among the creditors. As an alternative to liquidation, the CoC can dismiss the approval of the resolution plan and the resolution professional may put to vote any other plan received. However, the same is possible only when the CoC is convinced with the withdrawal plea of the resolution applicant.

Further, failure to implement the resolution plan undoubtedly would bring adverse consequences on the resolution applicant. Firstly, it would result in contempt of court, secondly, the Performance Security shall be forfeited. Performance security finds its mention in Regulation 36B of the IBBI (Insolvency Resolution Process for Corporate Persons) Regulations, 2016, sub-regulation 4A states that the Request for Resolution Plan (‘RFRP’) prepared on behalf of the corporate debtor shall require the resolution applicant to provide a performance security within the time specified in the RFRP, in case its resolution plan is approved by the CoC, it further provides that such performance security shall stand forfeited if after approval of resolution plan by the adjudicating authority, the resolution applicant fails to implement or contributes to the failure of implementation of that plan in accordance with the terms of the plan and its implementation schedule. An explanation to this sub-regulation provides that: ‘for the purposes of this sub-regulation, “performance security” shall mean security of such nature, value, duration and source, as may be specified in the request for resolution plans with the approval of the committee, having regard to the nature of resolution plan and business of the corporate debtor.’

In the case of Kridhan Infrastructure Pvt Ltd v Venkatesan Sankaranayan & Anr.[6] Hon’ble NCLAT observed that there had been an inordinate delay in implementation of the resolution plan by Kridhan Infrastructure Pvt Ltd, there was delay in i.) infusion of equity; ii.) upfront payment; and iii.) taking control of the management of the corporate debtor. The resolution applicant had repeatedly failed to honor its own commitments. The NCLAT therefore ruled that, ‘as the respondent resolution applicant has failed to implement the approved resolution plan, the performance guarantee of Rs. 5 crore furnished by the respondent resolution applicant stands forfeited in terms of Regulation 36B(4A) of CIRP Regulations.’

Concluding remarks

The Code, enacted in 2016, is still at a nascent stage. Even in the past, cases have been pushed into liquidation, CIRP being unsuccessful. The reasons for unsuccessful CIRP includes non acceptance of haircuts to the creditors, time lag, as seen in this case. Considering the same, not allowing withdrawal of resolution plans could act as a deterrent to the prospective RAs and a deterrent to the process of CIRP itself.

A resolution plan has all the ingredients of a valid contract. When the resolution applicant bids for reviving the CD and submits a resolution plan, he makes an ‘offer’ as per the Indian Contract Act, 1872. Such an offer, once accepted by the CoC becomes an agreement. And on approval of the resolution plan by the AA, the agreement takes the shape of a valid contract. While it is an accepted position of law that an offer is valid only for a stipulated period, yet if the validity is not mentioned on the face of it, the offer is valid only for a reasonable period. If that is the case, why should resolution plans be an exception? Is it the fact that a CD under IBC needs to be revived to keep the going concern status and is this fact enough to suppress the basic essentials of a contract? In our view, the resolution applicants being placed at a knife-edge is not appropriate and there should be sufficient provision to safeguard them.

[1] https://ibbi.gov.in//uploads/order/09603f1bdb3fb1e8bab88b34ee66a52c.pdf

[2] https://nclat.nic.in/Useradmin/upload/12787593265f74473351662.pdf

[3] https://ibbi.gov.in//uploads/order/af08668046e1cecfe990b17cff0937cb.pdf

[4] https://www.ibbi.gov.in/uploads/resources/fc8fd95f0816acc5b6ab9e64c0a892ac.pdf

[5] https://nclat.nic.in/Useradmin/upload/21011094875c8b923fbd407.pdf

[6] https://nclat.nic.in/Useradmin/upload/10066754915f574d5b81d4c.pdf

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!