Corporate climate change litigation: Increasing heat on boardrooms?

– Payal Agarwal and Neha Sinha | corplaw@vinodkothari.com

The importance of ESG aspects in the corporate world does not need an introduction in the current scenario. As the concept travels from the global conferences to the corporate boardrooms, so do the risks and opportunities of the same. Climate change has evolved from an “ethical, environmental” issue to one that presents foreseeable financial and systemic risks (and opportunities) over mainstream investment horizons, as discussed in detail in the Fiduciary Duties and Climate Change in the United States published by Commonwealth Climate and Law Initiative (CCLI). The corporate laws provide a general duty of the directors towards the protection of the environment, and therefore, directors cannot deny their responsibilities towards the same. The same has been dealt with at length in our writeup “Directors’ Liability towards Climate Change: Why Boards should be bothered”.

In this article, the authors try to look at the kinds of litigation in the field of climate change where corporations have been held accountable and identify the potential of litigation risks and the extent to which the directors of a company can be held liable for the climate change actions.

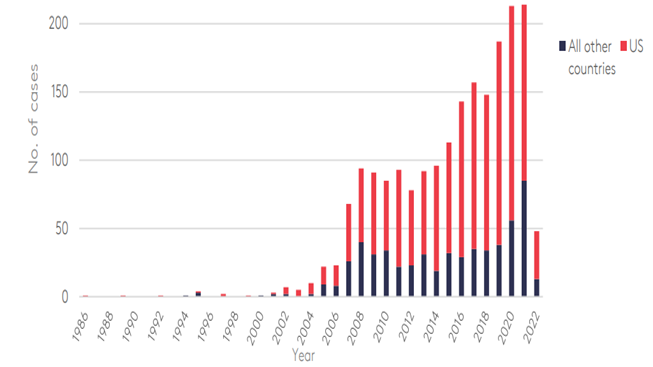

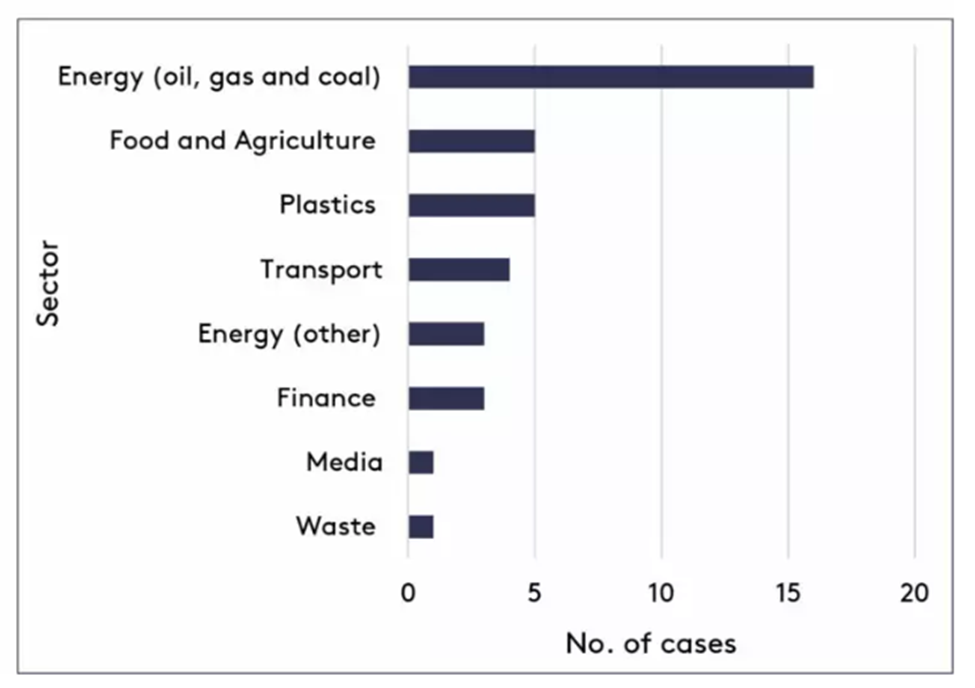

The Global trends in climate change litigation: 2022 snapshot published by the Centre for Climate Change Economics and Policy (CCCEP) in association with LSE and Gratham Research Institute indicates an increasing trend in the climate change cases over time, around the world (see Figure 1). These include cases filed against the policy decisions of the government as well as the cases against the climate-adverse actions of the companies. We are more concerned on the corporate cases front. Analysis suggests that the corporate climate cases are becoming more diverse and there is a shift in the type of defendants targeted. While historically, cases were generally lodged against the Carbon Majors[1] and other companies involved in the extraction of fossil fuels or the provision of fossil energy, a recent analysis shows that cases against corporate actors are also becoming far more diverse. More than half of cases were filed against defendants in other sectors, with food and agriculture, transport, plastics and finance all being targets in multiple cases (see figure 2).

Climate change litigation against companies: Making corporates accountable

As the climate litigations turn towards the corporates, the board of directors face an increasing risk of liability. In the calendar year 2021, around 38 cases were filed against private sector actors, as against 22 in the year 2020, around the world. This trend is only expected to move upward.

The discussion below tries to capture scenarios where corporates have faced (or are having to face) climate litigation, the grounds on which the action has been brought against them, counter-arguments or defenses which may have been provided by the corporates and the perspectives, if any, offered by the judiciary on the same.

As we note below, climate litigation is still a product of breach of fundamental duties of care and due diligence. In fact, a substantial part of jurisprudence around climate litigation has developed basic fundamental principles of care and diligence propounded and advocated in case laws not necessarily connected to climate and environment.

For instance, in Caremark Intern Inc Derivative Litigation,[2] the question of directors’ liability was interpreted in light of whether the actions/ inactions of the directors indicated good faith or not. (see discussion below). Although the Caremark ruling was in the context of alleged violation of laws applicable on health care service providers and no environmental aspect was involved in the same; yet the precedent has been invoked, rather successfully, in a plethora of environmental/social safety litigation cases against corporates, as we discuss further.

Caremark claims and director’s liability

The Caremark claims have its origin in Caremark Intern Inc Derivative Litigation. In the matter of Caremark, it was alleged that the directors breached their fiduciary duty of care to Caremark in connection with alleged violations by Caremark employees of federal and state laws and regulations applicable to health care providers. The case explains the context in which the potential liability for directorial decision will arise.

“Director liability for a breach of the duty to exercise appropriate attention may, in theory, arise in two distinct contexts. First, such liability may be said to follow from a board decision that results in a loss because that decision was ill advised or “negligent”. Second, liability to the corporation for a loss may be said to arise from an unconsidered failure of the board to act in circumstances in which due attention would, arguably, have prevented the loss.”

“Good faith” is the most important determinant of the existence of director’s liability. As observed in Caremark, “…compliance with a director’s duty of care can never appropriately be judicially determined by reference to the content of the board decision that leads to a corporate loss, apart from consideration of the good faith or rationality of the process employed.”

Another principle laid down in Caremark’s ruling is that the directors shall implement and monitor an adequate corporate information and reporting system.

“…a director’s obligation includes a duty to attempt in good faith to assure that a corporate information and reporting system, which the board concludes is adequate, exists, and that failure to do so under some circumstances may, in theory at least, render a director liable for losses caused by non-compliance with applicable legal standards.”

Precisely speaking, the following principles can be deduced out of the Caremark ruling (which have been later invoked and applied to various climate cases):

- Director’s liability may arise out of negligent decision-making.

- It may also arise out of the failure of the board to consider situations that required due attention.

- Good faith is the most important factor in assessing a director’s liability

- The board of directors need to formulate and maintain the adequacy of a corporate information and reporting system.

The Caremark principles have been subsequently advocated in an array of other cases indicating a breach of fiduciary duties of the directors. In Marchand v. Barnhill[3], also known as the Blue Bell’s case, the claim was raised against the board of directors of an ice-cream manufacturing company alleging failure of the company to monitor food safety at the board level.

“….it (Caremark) does require that a board make a good faith effort to put in place a reasonable system of monitoring and reporting about the corporation’s central compliance risks. In Blue Bell’s case, food safety was essential and mission critical. The complaint pled facts supporting a fair inference that no board-level system of monitoring or reporting on food safety existed.”

In Teamsters Local 443 Health Services & Insurance Plan v. John G. Chou, the allegations stated that a pharmacy company sold unsterile and contaminated drugs and that directors acted in bad faith by failing in their duty to oversee operations of the pharmacy. Denying the motion to dismiss the claims against the directors, the Court held that the directors had ignored red flags and also permitted a grossly inadequate reporting system with respect to the business line in which the pharmacy operated. In Re Clovis Oncology, Inc. Derivative Litigation[4] also, the Caremark claim was admitted against the board of directors on the failure of the directors to act upon the red flags presented to them on the mission critical issues of the company.

In William Hughes v. Xiaoming Hu, it was claimed that the directors breached their fiduciary duties by wilfully failing to maintain an adequate oversight mechanism, disclosure controls and procedures, and internal controls over financing reporting. Referring to Caremark, the Court observed that directors may be held liable if they act in bad faith in the sense that they made no good faith effort to ensure that the company had in place any system of controls. Even though an audit committee existed, the committee did not hold regular meetings or devote adequate time to its work. The Court held that the board of directors, acting through its audit committee, had failed to provide meaningful oversight over the company’s financial statements and system of financial controls.

Similarly, inThe Boeing Company Derivative Litigation, the allegations were that Boeing’s directors and officers had failed to monitor the safety of airplanes, to ensure the existence of reasonable safety information and reporting systems, and to actively monitor such systems despite being alerted of the safety concerns associated with the airplanes. The Court observed that an oversight claim under Caremark can be pled only only with particularised facts to allow a reasonable inference that the directors acted inconsistently with his fiduciary duties and that he knew he was acting so. For a claim under Caremark, lack of good faith is a necessary element. The Court held that they did not monitor the safety of airplanes on a regular basis and also ignored the red flags concerning the safety, and hence, denied the motion to dismiss the claim under Caremark.

Link between Caremark claims and climate change

As we discuss the success of Caremark claims in recent years in enforcing the director’s liability against breach of their fiduciary duties, please note that there are no known instances where the same has been used to enforce the board’s liabilities towards climate change. There are a handful of literary works that either supports or defends the relationship between Caremark claims and climate litigations. For example, Pace and Trautman[5] suggest that “Caremark doctrine would prove a poor policy fit for addressing climate change. To ask it to do so would be to ask too much, although it can complement other legal efforts better suited to addressing climate change”. On the contrary, it is also projected[6] that much of the climate litigation is likely to come in the form of Caremark claims, on the basis of failure of the board to implement suitable and adequate risk control measures.

The Caremark claims are not completely aloof from the ESG concerns in an organization, and in the past, there have been successful cases[7] that have upheld the enforceability of Caremark claims in the “mission critical” ESG operations of a company. Climate change is definitely one of the significant risks various businesses are exposed to, and therefore, we do find the probability of bringing a Caremark claim against the failure of directors to design and implement adequate risk management infrastructure against the climate risks.

Grounds on which corporate can be held liable for climate concern

Duty of care

In the Dutch case of Milieudefensie et al. v. Royal Dutch Shell[8] before the District Court of The Hague, relief was claimed by the plaintiffs on the ground of “duty of care”. The case was made by the non-governmental organizations working for the cause of GHG emission reduction and climate change, against the Shell group of companies, being the major fossil fuel companies. The claim was based on the following –

“RDS[9] has an obligation, ensuing from the unwritten standard of care pursuant to Book 6 Section 162 Dutch Civil Code to contribute to the prevention of dangerous climate change through the corporate policy it determines for the Shell group… RDS violates this obligation or is at risk of violating this obligation with a hazardous and disastrous corporate policy for the Shell group, which in no way is consistent with the global climate target to prevent a dangerous climate change for the protection of mankind, the human environment and nature.”

In the given case, the court held a view that RDS’ adoption of the corporate policy for Shell group constitutes an independent cause of the damage, which may contribute to environmental damage and therefore an ‘event giving rise to the damage’. The responsibility to respect human rights is not an optional responsibility for companies, and much may be expected from RDS, having a policy-setting position in the Shell group, which is a major player on the worldwide market of fossil fuels and is responsible for significant CO2 emissions, which exceed the emissions of many states and which contributes towards global warming and a dangerous climate change in the Netherlands and in the Wadden region with serious and irreversible consequences and risks for the human rights of Dutch residents and the inhabitants of the Wadden region.

While dealing with the activities that have caused environmental damage, the court clarified that actions include omissions. Companies may be expected to identify and assess any actual or potential adverse human rights impacts with which they may be involved either through their own activities or as a result of their business relationships, and subsequently, take appropriate action for correction. In light of this, the Court ordered RDS to limit the aggregate annual volume of CO2 emissions by at least 45% at the end of 2030.

Notably, ClientEarth, a shareholder of the Shell Inc, has also initiated legal action against the Company on the ground of breach of its duties under sections 172 and 174 of the UK Companies Act, which requires it to act in a way that promotes the company’s success, and to exercise reasonable care, skill and diligence. It is alleged that “Shell is seriously exposed to the risks of climate change, yet its climate plan is fundamentally flawed. In failing to properly prepare the company for the net-zero transition, Shell’s Board is increasing the company’s vulnerability to climate risk, putting the long-term value of the company in jeopardy”.

Duty to cease contribution to climate change

Climate change is a global issue, and everyone (individual/ organisation/ corporates) has a responsibility to not do anything which aggravates the concern.Hence, a lot of cases have been initiated on this ground – although most of the cases are either pending conclusion, or in some cases, the relief was denied on such grounds.

In the case of Smith v Fonterra Co-Operative Group Ltd[10] before the New Zealand High Court,, the plaintiff sought relief against the release of greenhouse gases by the defendants on grounds of public nuisance, negligence and a duty, cognisable at law, to cease contributing to damage to the climate system. While the New Zealand High Court striked off the first two grounds, the third has been accepted on the grounds that this may further evolve the common laws and the plaintiff has been instructed to proceed further on the same. Both the parties had filed respective appeals for admission of/ rejection of the cause of action, and the appeal of the defendant was upheld, while dismissing the appeal filed by the plaintiff. The plaintiff has moved the Supreme Court against the same, and it is noteworthy that the SC has granted leave of appeal to the same.

In Four Islander of Pari v. Holcim, four inhabitants of the Indonesian island of Pari sued Swiss building material company Holcim which is a major emitter of greenhouse gases on the grounds that the company’s emissions had lead to rise in sea and levels and floods, threatening the livelihoods of the inhabitants of Pari which is based on fishing and tourism.

In County of San Mateo v. Chevron Corp., the petitioners alleged the oil company’s extraction, refining and formulation of fossil fuels has substantially contributed to global warming, causing the petitioning counties to suffer huge losses from flooding due to rise in sea level. The U.S. Court of Appeals affirmed that even though its a case of inter-state pollution, the climate case brought by state local authorities should be returned to the state. The case is yet pending final adjudication.

InNative Village of Kivalina v. ExxonMobil Corp., an action was brought against the giant oil company, under the federal common law of nuisance, for its contribution to climate change caused by its greenhouse emission, leading to global warming and melting of Arctic ice caps, which exposed the village of Kivalina in Alaska to erosion and flooding. Although the Court of Appeals dismissed the claim stating that claim for damages under federal common law displaced by a relief existing in an environmental statute, the U.S. Supreme Court allowed the appeal and issued a writ of certiorari against the Court of Appeals’ decision.

In the case of Public Ministry of the State of São Paulo v. KLM before the Superior Court of Justice of Brazil, a public civil action suit was filed by the Public Ministry of the State of São Paulo against an airline company for allegedly causing environmental damage with its activities. The case was not sustained on the ground that there was an environmental licensing process already carried out and therefore, there is no need to talk about the alleged implicit act.

Besides, there are several cases relating to climate change against private corporations which are pending across several jurisdictions.

The first climate change litigation in China is also focussed around the activities of a company contributing to the adverse impacts of climate change. In The Friends of Nature Institute v. Gansu State Grid, a complaint was raised against the failure of a grid company to source its electricity from renewable sources and substitution of the same with coal-fired power, thereby leading to increase of air pollution and GHG emissions, which has direct implications for climate change. The case is still pending for the decision of the court.

In Federal Environmental Agency (IBAMA) v. Siderúrgica São Luiz Ltd. and Martins, an environmental class action has been filed in a Civil Federal Court in Brazil, against a steel company and its managing partner, for environmental and climate damages allegedly caused by the company’s continuous and fraudulent use of illegally sourced coal in its units.In the absence of any legal provision imposing the need for the environmental integrity by companies that explore activities potentially harmful to the environment, the request for injunction against the activities of the steel company was rejected. The matter is currently pending for need of further information and documents.

A series of litigations[11] have been witnessed in Indonesia around the burning of palm plantation land clearing resulting in loss of carbon sinks. These lawsuits have been admitted under strict liability rule of Articles 88 Environmental Protection and Management Act and the corporations have been adjudged guilty.

Alignment of investments with climate targets

While there has been rising awareness on environmental-friendly processes and operations; of-late, the role of capital and capital providers too, is being increasingly recognised in mitigating climate risks. Going by the concept of ‘responsible investing’.[12]Litigations have also been witnessed against the financial institutions granting loans/ credit facilities to the companies which use them for carbon-intensive projects or similar such projects.

A civil climate action was filed against a national development bank, BNDES (Brazil’s Development Bank) and BNDESPar, the bank’s investment arm, very recently in June, 2022. The allegations pertain to exclusion of climate criteria in making investment decisions, holding equity position in some of the most carbon-intensive sectors and non-reporting of the carbon emissions associated with its investment portfolio. The case is pending for final judgment by the court.

ClientEarth had also filed a suit against the Belgian National Bank for failing to meet environmental, climate, and human rights requirements in making decisions for purchase of bonds from fossil fuel and other greenhouse-gas intensive companies. The application was rejected on procedural grounds and an appeal has been preferred against the same.

In McVeigh v. Retail Employees Superannuation Trust, a suit was filed against an Australian pension fund on account of failure to provide information related to climate change business risks and any plans to address those risks. The matter reached a settlement when the Australian pension fund agreed to incorporate climate change financial risks in its investments and implement a net-zero by 2050 carbon footprint goal.Pertinently, the defendant (Retail Employees Superannuation Trust) duly acknowledged the link of between climate change and financial markets and the impact of climate change on financial markets as climate change is “a material, direct and current financial risk to the superannuation fund across many risk categories, including investment, market, reputational, strategic, governance and third-party risks.”

Violation of constitutional rights

In most of the public action suits filed against the corporations or governments for their actions hampering human rights, aid has been taken of the constitutional rights of the citizen. For instance, in Baihua Caiga et. al., v. PetroOriental S.A., a constitutional injunction was filed against a Chinese oil company, on account of violation of various constitutional rights such as –

“(i) the rights of nature as GHG emissions altered the carbon cycle, (ii) the right to enjoy a healthy and ecologically balanced environment as climate change breaks down the ecological balance, (iii) the right to food because applicants have seen their food security and food sovereignty diminished, (iv) the right to water because droughts and floods are becoming more extreme and unpredictable, limiting access, quality, quantity and availability of water, (v) the right to health because the scarcity of food and traditional medicines affects the applicants’ wellbeing, (vi) the right to land and territory because the applicants’ ability to enjoy natural resources through ancestral practices has been limited, (vii) and the right to life and a dignified life because the applicants’ existence is threatened, and the minimum conditions to continue with their life projects are not met.”

The case was dismissed on the ground that the plaintiffs had not sufficiently demonstrated how the actions of the defendant violate the rights of nature or any constitutional right deriving therefrom.

In Sendai Citizens v. Sendai Power Station, Sendai High Court of Japan, injunction was sought against a power plant, having the threat of damage to the appellant’s life and bodily integrity by the health impact due to the exposure to the air pollutants. The judgment was pronounced in favour of the defendant since there was no sufficient evidence to recognize concrete danger to the appellant’s health.

In Citizens’ Committee on the Kobe Coal-Fired Power Plant v. Kobe Steel Ltd., et al, a petition for injunction has been filed in the Kobe District Court of Japan, against the construction of new coal-fired units, on the grounds of violation of right to a healthy and peaceful right.

In Kaiser, et al. v. Volkswagen AG, Regional Court of Braunschweig (Germany), a case has been filed against the ignorance of the car manufacturer towards committing to achieve carbon neutrality in the production and intended use of internal combustion engine cars. The petition is raised on the grounds of breach of duty of care as well as constitutional validity of the same. Similar petitions have been filed against BMW and Mercedes-Benz AG.

Scope of corporate responsibility

Having discussed the grounds on which corporate responsibility arises towards climate change, another important consideration may be with respect to the extent of liability. Whether the climate responsibility is considered on a standalone basis, or whether, one or more companies can be held liable for the activities of other companies on a group level.

Responsibility across business relationships

The corporate responsibility towards climate change may arise out of one’s own activities as well as across the “business relationships” of the companies. In the matter of Milieudefensie (supra), the extent of responsibility has been explained as follows –

“4.4.17. The UNGP are based on the rationale that companies may contribute to the adverse human rights impacts through their activities as well as through their business relationships with other parties.

XXX

“Business relationships” are understood to include relationships with business partners, entities in its value chain, and any other non-state or state entity directly linked to its business operations, products or services. The responsibility to respect human rights encompasses the company’s entire value chain. Value chain is understood to mean:

“the activities that convert input into output by adding value. It includes entities with which it has a direct or indirect business relationship and which either (a) supply products or services that contribute to the enterprise’s own products or services, or (b) receive products and services from the enterprise.”

Duty of care of parent in relation with the activities of the subsidiary

The UK Supreme Court in Vedanta Resources PLC and another v. Lungowe and Others [2019] UKSC 20, has indicated that a duty of care can exist between a parent company and those affected by the operations of the parent’s subsidiaries, and the existence of such duty depends on the facts of each case, and mostly, on the extent of intervention of the parent in the activities of the subsidiary.

“…Vedanta may fairly be said to have asserted its own assumption of responsibility for the maintenance of proper standards of environmental control over the activities of its subsidiaries, and in particular the operations at the Mine, and not merely to have laid down but also implemented those standards by training, monitoring and enforcement, as sufficient on their own to show that it is well arguable that a sufficient level of intervention by Vedanta in the conduct of operations at the Mine may be demonstrable at trial, after full disclosure of the relevant internal documents of Vedanta and KCM, and of communications passing between them.”

The Court held that the duty of care “…depends on the extent to which, and the way in which, the parent availed itself of the opportunity to take over, intervene in, control, supervise or advise the management of the relevant operations (including land use) of the subsidiary.”

InCaparo Industries Plc v. Dickman,[13] the House of Lords had formulated a threefold test for duty of care: foreseeability of damage, existence of a proximate relationship between the party owing duty of care and the party to whom such duty is owed, and the situation should be one in which the court considers it fair, just and reasonable that the law should impose a duty of care upon one party for teh benefit of the other.

InOkpabi v. Royal Dutch Shell Plc (2021) UKSC too, the question before the UK Supreme Court was upon the duty of care of a parent company in relation to the activities of the subsidiary. Here, it has to be noted that in order to hold a parent company liable for the activities of the subsidiary, the point of relevance is not the “existence of control” but the “extent of control”. Relevant extracts from Okpabi judgment below –

“In considering that question, control is just a starting point. The issue is the extent to which the parent did take over or share with the subsidiary the management of the relevant activity (here the pipeline operation). That may or may not be demonstrated by the parent controlling the subsidiary. In a sense, all parents control their subsidiaries. That control gives the parent the opportunity to get involved in management. But control of a company and de facto management of part of its activities are two different things. A subsidiary may maintain de jure control of its activities, but nonetheless delegate de facto management of part of them to emissaries of its parent.”

Who can be a claimant?

The general rule of law states that those having an interest over a matter or those directly affected by the impugned act or those who have suffered a legal injury by violation of their legal rights or legally protected interest, can file a claim. Similar is the position in the Netherlands, where a claimant must have an independent, direct interest in the instituted legal proceedings as per the Book 3 Section 305a Dutch Civil Code. Article 3: 305a of Book 3 of Dutch Civil Code deals with collective actions or class actions. Pursuant to the said provision, a foundation or association with full legal capacity that has objection to protect specific interests, may bring legal claims that intend to protect similar interests of other persons.[14]

Under the US law, a plaintiff will have the standing to sue only if the following three conditions are met:

- the plaintiff has suffered an injury in fact,

- that is fairly traceable to the defendant’s misconduct (causation) and

- is capable of being redressed by the court.[15]

Several cases have been filed in jurisdictions by citizens of other countries on violation of human rights from the cross-border impact of climate change, tortious liability and also the domestic law of the forum country.[16] In such cases, the issue of liability of greenhouse gas emissions in a country for the adverse impact caused in other jurisdictions is involved.[17]

In India also, the rule of locus standi is well established for filing of suit. As per the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908, any right to relief in respect of the same act or transaction exists in persons, then such persons may be joined as plaintiffs in a suit. The scope of locus standi rule was discussed by the Supreme Court in the matter of S.P. Gupta v. Union of India[18] . The conventional law regarding legal capacity standing of a person to sue or locus standi is that the “judicial redress is available only to a person who has suffered a legal injury by reason of violation of his legal right or legal protected interest by the impugned action of the State or a public authority or any other person or who is likely to suffer a legal injury by reason of threatened violation of his legal right or legally protected interest by any such action. The basis of entitlement to judicial redress is personal injury to property, body, mind or reputation arising from violation, actual or threatened, of the legal right or legally protected interest of the person seeking such redress.”[19] Hence, a person who has suffered legal injury can sue in the courts of law. As was also held in the case of Vodyarapu Ravi Kumar v. Government of Andhra Pradesh,[20] “a person must have sufficiency of interest to sustain his stand to sue.”

However, in India, the concept of public interest litigation (PIL) has developed over time, especially in cases of environmental litigation. In case of PIL, be it in cases of climate litigation or otherwise, the rules of locus standi have been relaxed for any member of the public to look into the grievances of the deprived or underprivileged.[21] Only a person acting bonafide and having sufficient interest in the proceedings, without any motives for personal gain or political motivation or other oblique considerations, not being a meddlesome interloper or a busybody,[22] is allowed to approach the courts with a PIL.

In cases of climate and environmental litigation, the parameters for legal capacity to sue are not stringent to encourage and allow public-spirited citizens to bring to the Court’s attention any environmental damage. Right to clean, healthy and safe environment being a part of Article 21 of the Constitution of India,[23] the petitioner can move the Supreme Court under Article 32 or approach the High Courts under Article 226. However, there are alternative efficacious remedies available before the writ jurisdiction. The petitioners can approach the NGTs for contravention of the environmental statutes.

The polluters can be held liable under the environmental statutes, Indian Penal Code, 1860, torts and curtailment of the fundamental right to a clean environment under Article 21.

Apart from the constitutional remedy and litigations within the specific environmental legislations, liability can also be invoked on the directors of the company under section 166 of the Companies Act, 2013.[24] In M.K. Ranjitsinh v. Union of India,[25] the Supreme Court had noted the duty of a director towards the environment. The Court observed that “section 166(2) of the Companies Act, 2013 ordains the Director of a Company to act in good faith, not only in the best interest of the Company, its employees, the shareholders and the community, but also for the protection of environment.”

Climate litigation being a matter of larger public interest, legal action may also be initiated by way of class action suits. The Code of Civil Procedure, 1908 (CPC) provides for representative suits or class actions[26] wherein numerous persons having the same interest in one suit, one person or more than one such persons may sue on behalf of all others, with the permission of the Court. Hence, for representative action or class action of suits, commonality of interest is essential. Further, any person can also sue for an injunction against causing public nuisance or other wrongful act likely to affect the public.[27] With the permission of the court, person(s) can institute a suit for declaration of injunction even when no damage is caused to such person(s) by reason of such public nuisance or wrongful act.

In the United Kingdom, class actions suits or representative suits, where more than one person has the same interest in a claim, the claim may be brought by one or more persons who have the same interest as the representatives of other persons who have the same interest.[28] While the same interest does not mean that all represented parties must be in exactly the same position, the interest must be the same for all practical purposes.[29]

Similarly, in the U.S., one or more members of a class may sue as representative on behalf of all members only if all of the following four conditions are met: the class is so numerous that joinder of all members is impracticable; there are questions of law or fact common to the class; the claims of representative parties are typical of the claims of the class; the representative parties will fairly and adequately protect the interest of the class.[30]

The class action device is an exception to the usual rule that litigation is conducted by and on behalf of the individual named parties only.[31] As was stated by the U.S. Supreme Court, “the class action device saves the resources of both the courts and the parties by permitting an issue potentially affecting every [class member] to be litigated in an economical fashion.”[32]

The environmental cases can also be filed under these provisions as a class action suit by such persons affected from the environmental damage on behalf of a group affected persons.

General reliefs claimed for under climate litigation

Climate litigations generally involve a wider public interest rather than personal interests. Therefore, personal reliefs are generally not sought for in such matters. The relief mostly includes an order or injunction against the activities causing adverse climate change.

For instance, in the case of Milieudefensie (supra), the relief claimed against the parent company of a group of companies and legal entities engaged in the energy-intensive business was to limit or cause to be limited the aggregate annual volume of all CO2 emissions into the atmosphere due to the business operations. In Four Islander of Pari (supra), the petitioners sought proportional compensation for climate change related damage to Pari and reduction of the company’s CO2 emission and co-financing of adaptation measures by the company. The adjudication in this case is pending.

In BNDES and BNDESPar (supra), the petitioners sought that the bank (BNDES and its investment arm BNDESPar) adopt transparency measures and prepare a plan and mechanisms to commit their investments and divestments to the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions.

In County of San Mateo v. Chevron Corp., the relief sought was damages for responding to flooding and putting in place adaptation measures to the impact of such global warming. [33] The case is pending final adjudication.

In some cases, the relief also expands well into the claims for monetary compensation. InNative Village of Kivalina v. ExxonMobil Corp., petitioners in this case sought damages and not injunctive relief, under the federal common law of public nuisance. The case is pending final adjudication.

Hence, punitive and compensatory damages has been sought against corporations for redressing the loss caused due to climate change on account of the corporations’ activities and costs relating to devising and putting in place of measures for tackling climate change in future.

In environmental damage cases, damages are awarded to cover material damage to environmental resources, and includes lost income or costs related to emergency responses, clean-up, impact studies, restoration, or monitoring.[34] This regime is suited to compensate an injured person by directing the responsible person to pay the economic cost of resulting damage. However, pure environmental damage may be incapable of calculation in economic terms. Hence, the approach towards environmental compensation is payment of the reasonable costs of restoration measures, reinstatement measures or preventative measures.[35] Hence, the compensation regime under environmental damage would bind the director with a civil liability.

Hence, the reliefs sought range from damages to injunction against the polluting corporation to reduce CO2 emissions and put in place mechanisms to stop climate damaging practices and actively work towards preserving the ecology.

In India as well, the reliefs include environmental compensation and injunctions and directions against corporations in respect of their activities causing pollution. The manner of awarding monetary compensation against environmental damage and quantification of damages in the context of India has been discussed in details below.

Climate Litigation in India vis-a-vis Corporations

At the outset, the authors note that India is yet to see climate litigation against corporations. In the context of India, the cases are majorly on environmental pollution, which may have a link with climate change but not pertinently placed. The assessment of damages in climate related cases may have the same approach on the basis of evaluation of short term as well as long term impacts of the business activities on climate change and the consequent effect on the ecology and people.

An absolute liability is imposed on the polluter to compensate for the harm caused. The principle of ‘Polluters Pay’ has evolved in India which demands that the financial costs of preventing or remedying damage caused by pollution lies with the undertakings which caused such pollution.[36]Petitioners invoke writ jurisdiction for the issuance of writ of mandamus against the State and its instrumentalities to compel them to perform their duties effectively, which in environmental damage cases include, issuance of environmental clearance certificate to corporations only after due diligence and regulating the corporations’ activities affecting environment. A general trend in India in awarding compensation against environmental damage has been discussed below.

In the Indian Council for Enviro-Legal v. Union of India,[37] case, the quantification of the damages was based on cost of restoration and remedial measures. The amount is paid to the Central Government or recovered from the polluter by the Central Government. The Supreme Court can issue directions for the removal of the pollutant, for undertaking remedial measures and also impose the cost of the remedial measures on the offending industry and utilize the amount recovered for carrying out the remedial measures.

In the case of Paryavaran Suraksha Samiti v. Union of India,[38] the NGT issued several directions to the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) for setting up of effluent treatment plant and discussed the allocation of funds such sst up wherein 50% of the funds were to be provided by the Central Government, 25% by the State Government and 25% to be arranged by way of loans which was to be repaid by user industries.

The CPCB had released a Report titled Report of the CPCB In-house Committee on Methodology for Assessing Environmental Compensation and Action Plan to Utilize the Fund which lays down the methodology to assess and recover compensation for damage to the environment and utilize such amounts in terms of an action plan for protection of the environment.

In Tribunal on its own Motion v. Ministry of Environment, Forest & Climate Change & Ors.,[39] NGT considered the issue of remedies against pollution caused by firecrackers, worsening the effect of Covid-19 and posing health hazards to vulnerable groups. The Tribunal computed the compensation to be paid by defaulters in accordance with the guidelines laid down by CPCB. The District magistrate was directed to recover compensation from violators and deposit the amount in a District Environment Compensation Fund. Any victim of pollution was permitted to approach the District Magistrate for claiming the compensation, substantiating the evidence of damage. In case no such claim was preferred after collection of compensation, such an amount could be spent for restoration of the environment.

The Precautionary Principle is an integral part of environmental jurisprudence and sustainable development. As enunciated by the Supreme Court,[40] this principle envisages the following:

- “Environment measures- the State Government and statutory authorities must anticipate, prevent and attack the causes of environmental degradation;

- Where there are threats of serious and irreversible damage, lack of scientific certainty should not be used as the reason for postponing measures to prevent environmental degradation;

- The onus of proof is on the actor or the developer/industrialist to show that his action is environmentally benign.”

In the Vellore Citizens case, the Supreme Court ordered for the constitution of an authority to deal with the environmental issues. Such an authority, with the assistance of experts and after giving an opportunity to the polluters, was given responsibility to assess the loss to ecology and identify the individuals affected by such pollution. The authority was directed to determine the quantum of compensation to be paid to the affected individuals. Thereafter, the authority had to assess the compensation to be recovered from the polluters as the cost of reversing the damaged environment and for payment to affected individuals. In case the polluter industry evaded paying the compensation, the authority was mandated to direct the closure of the industry.

In Sterlite Industries (India) Ltd v. Union of India,[41]the Supreme Court had ordered the polluting company to deposit a compensation of Rs. 100 crore with the District Collector. The said amount would be kept in a fixed deposit in a national Bank for a minimum of five years, and when it expires, the interest therefrom would be spent on suitable measures for improvement of environment.

Similarly, in Anupam Raghav v. Union of India,[42] NGT ordered the payment of compensation by thermal power plants located across several states including Haryana, Jharkhand, Karnataka, for discharge of effluent and unscientific disposal of fly ash leading to environmental damage.

From the precedents set by the Supreme Court as well as NGT, the principle emerges that the quantification of compensation is done on the basis of the remedial actions for cost of restoration of ecology and compensation to the individuals affected by the pollution. Hence, the polluting industries and corporations would be liable to pay such an amount of compensation in accordance with the parameters set out by statutory bodies and on the basis of the quantum required for restoration purposes and for compensating the affected people. Further, the Supreme Court observed that a person guilty of causing pollution can also be made to pay exemplary damages so as to impart a deterrent effect for others against causing pollution.[43]

Since the impacts of climate change cannot be remedied by simply adopting restoration measures, courts must take a wide approach in tackling the issue of monetary compensation and not limit it to only costs of restoration.

Approach expected from the board of directors

As may be evident from the discussion above, directors have a duty towards protection of the environment, and failure to do so may lead to liability for breach of duty under the corporate laws, apart from the violations of applicable environmental laws.

The scope of the director’s duty to act in good faith for the protection of the environment is wide enough to include risks posed by climate change on corporations.[44] The director has to exercise his duties with due and reasonable care, skill and diligence such that the operations of the company do not contribute to climate change.[45] For violation of these provisions, in India, the director would be punishable with fine not less than one lakh rupees and could extend to five lakh rupees.[46]

Following the principle laid down in Caremark, lack of good faith in carrying out the directorial duty is an essential component for the test of breach of duty of care. In this context, we briefly put out the approach that is expected of the board of a company to safeguard against a future legal claim against climate claims.

- Sufficient internal controls towards identification of red flags and climate risks emerging out of the operations of the company

- Setting a risk control framework and taking corrective measures towards mitigation of climate risks

- Oversee smooth implementation of the risk identification and mitigation mechanism

- Alignment of the operations of the company with the ESG goals

- Devise comprehensive policies which would actively contribute towards curbing climate change, recuperating ecology and preventing environment degradation. The policies should be in consonance with the climate related principles being framed by international bodies and updated norms for corporate governance.

- Develop policies mitigating climate risks posed by the company’s activities. It can identify and assess the present and future, short term as well long term climate risks associated with the company’s operations.

- Review of the working of the mechanisms adopted by the board

Concluding Remarks

With the perils of climate change growing closer, it’s imperative that corporations take a positive step towards taking responsibility for their actions affecting the environment. The operations of companies can have a large impact on the surrounding ecology and hence, the directors would be held accountable for dereliction of duty towards the environment by allowing the company to operate in that manner. Therefore, the aim of the Board should be to develop holistic and sustainable development policies and strengthen their corporate governance.

Our resource center on Business Responsibility and Sustainable Reporting can be accessed here –

[1] Carbon Majors is a term that refers to a list of energy and cement companies identified by Richard Heede (2014) and the Climate Accountability Institute through an assessment of the historical contributions of these companies to greenhouse gas emissions. Heede attributed 63% of the carbon dioxide and methane emitted between the years 1751 and 2010 to a mere 90 entities. Out of these, 50 are investor-owned companies, 31 are state-owned and the remaining nine are government-run. See: https://climateaccountability.org/.

[2] 698 A.2d 959, 967 (Del. Ch. 1996)

[3] 212 A.3d 805 (2019).

[4] 2019 WL 4850188 (Del. Ch. Oct. 1, 2019).

[5] H, Justin Pace & Lawrence J. Trautman,Climate Change and Caremark Doctrine, Imperfect Together (2022).

[6] https://www.wlrk.com/webdocs/wlrknew/ClientMemos/WLRK/WLRK.26750.20.pdf

[7] https://www.jdsupra.com/legalnews/caremark-and-mission-critical-esg-6914783/

[8] An appeal is pending by RDS against the judgment of the District Court.

[9] RDS is the parent company of the Shell group and is responsible for the preparation of the policies to be implemented across the group levels.

[10] [2021] NZCA 552.

[11] See Ministry of Environment and Forestry v. PT Palmina Utama; Ministry of Environment and Forestry v. PT Arjuna Utama Sawit; Ministry of Environment and Forestry v. PT Asia Palem Lestari; Ministry of Environment and Forestry v. PT Rambang Agro Jaya.

[12] United Nations – Principles for Responsible Investment defines responsible investment as “a strategy and practice to incorporate environmental, social and governance (ESG) factors in investment decisions and active ownership.”

[13] [1990] 2 AC 605.

[14] Dutch Civil Code, Book 3, Article 3: 305a.

[15] U.S. Constitution, Article III.

[16] See Four Islanders of Pari v. Holcim.

[17] See Luciano Lliuya v. RWE AG.

[18] 1981 Supp. SCC 87.

[19] S.P. Gupta v. Union of India, 1981 Supp. SCC 87.

[20] Public Interest Litigation Nos. 394 and 416 of 2013, High Court of Andhra Pradesh (dated 20.11.2013).

[21] V. Annaraja v. The Secretary to the Union of India, Ministry of Environment and Forests, Writ Petition No. 3822 of 2019.

[22] S.P. Gupta v. Union of India, 1981 Supp. SCC 87.

[23] Rural Litigation and Entitlement Kendra v. State, AIR 1988 SC 2187; M.C. Mehta v. Union of India, AIR 1987 SC 1086.

[24] Companies Act, 2013, section 166. Duties of directors. (2) A director of a company shall act in good faith in order to promote the objects of the company for the benefit of its members as a whole, and in the best interest of the company, its employees, the shareholders, the community and for the protection of environment.

[25] Writ Petition (Civil) No. 838 of 2019.

[26] Code of Civil Procedure, 1908, Order 1 Rule 8.

[27] Code of Civil Procedure, 1908, section 91.

[28] Civil Procedure Rule, rule 19.6.

[29] Harrison Jalla and Abel Chujor v. Shell, [2020] EWHC 2211 (TCC).

[30] Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, rule 23.

[31] Califano v. Yamasaki, 442 U.S. 682 (1979).

[32] General Telephone Co. v. Falcon, 457 U.S. 147 (1982).

[33] Geetanjali Ganguly, Joana Setzer & Veerle Heyvaert, If at First You Don’t Succeed: Suing Corporations for Climate Change, 38 (4) Oxford Journal of Legal Studies 841-868 (2018).

[34] Environmental Liability & Compensation Regimes: A Review, United Nations Environment Programme (2003).

[35] Environmental Liability & Compensation Regimes: A Review, United Nations Environment Programme (2003).

[36] Indian Council for Enviro-Legal v. Union of India, 1996 SCC (3) 212.

[37] 1996 SCC (3) 212.

[38] Original Application No. 593/2017 (W.P. (Civil) No. 375/2012).

[39] Original Application No. 249/2020, NGT Principal Bench, New Delhi.

[40] Vellore Citizens Welfare Forum v. Union of India, (1996) 5 SCC 647.

[41] Civil Appeal Nos. 2776-2783 of 2013.

[42] Original Application No. 164/2018, NGT Principal Bench, New Delhi.

[43] M.C. Mehta v. Kamal Nath.

[44] Umakanth Varottil, Director’s Liability and Climate Risk: White Paper on India, Commonwealth Climate and Law Initiative (2021).

[45] Companies Act, 2013, section 166(3).

[46] Companies Act, 2013, section 166(7).

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!